A woman writes: “What was the legislative intent of having the petitioner sign under oath in a civil TRO [temporary restraining order]…?”

The question seems ingenuous enough. The answer, obvious to anyone who’s run afoul of the restraining order racket, is that people lie.

Less ingenuous is the state’s faith that a warning against perjury in fine print on the last page of a restraining order application (that its petitioner has just spent 20 minutes filling out) is going to discourage a liar from signing his or her name to the thing. (In my county this “warning” reads, “Under penalty of perjury, I swear or affirm the above statements are true to the best of my knowledge….” No explanation of perjury or its penalties is provided.)

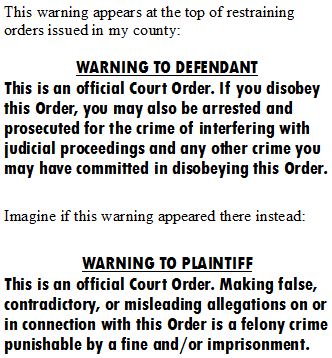

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.

Led by the dated dictum that it should in no way discourage would-be restraining order petitioners, the state relegates its token warning against giving false testimony to the tail end of the application where it will most likely be disregarded.

And why not? Perjury is never actually prosecuted.

What this woman’s question reveals is (1) that the average petitioner doesn’t equate statements made on restraining order applications and in affidavits with sworn testimony given in a courtroom, and (2) that neither the consequences to plaintiffs of making inaccurate, misleading, or intentionally false statements to the court nor the consequences to defendants of being emotionally saddled with a restraining order are seriously weighed.

After a more complete digestion of this woman’s question, the unavoidable answer to it is that the legislative intent of having the petitioner sign under oath is plausible deniability of the process’s inviting and rewarding fraudulent abuse.

Copyright © 2012 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com