“Orders for protection represent a legislative attempt to incorporate distinct features from both civil law and criminal law. On the one hand, a private litigant can initiate judicial proceedings to seek redress against another private individual. On the other hand, criminal penalties, such as fines and incarceration, will attach if a protection order is violated. Unlike both civil and criminal proceedings, protection order actions involve a great deal of informality, with the end result being an order for protection that is often issued on an ex parte basis without the benefit of a full evidentiary hearing.

“Many aspects of Nevada law in this area can best be described as ‘murky,’ with virtually no critical or scholarly study available to assist Nevada’s courts. Moreover, statistical information about protection orders in Nevada is almost non-existent.”

—Staff attorney Joe Tommasino, Las Vegas Justice Court

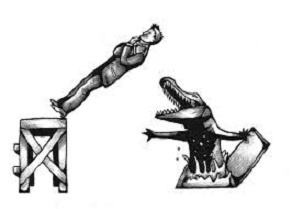

The first thing reporters need to grasp about restraining orders is that they’re a kluge (a Frankenstein’s monster crudely stitched together from dubiously compatible parts). For plaintiffs (accusers), they merge the most favorable aspects of civil and criminal prosecutions; for defendants, the least favorable.

The scales of justice are tipped from the start.

The scales of justice are tipped from the start.

Restraining orders allow a “private litigant [to] initiate judicial proceedings to seek redress against another private individual” just as civil lawsuits do (though restraining order applications by contrast are typically processed free of charge). They’re also adjudicated according to the lowest civil standard of proof (“preponderance of the evidence”). State standards vary rhetorically, but the criterion for rulings is basically the same: whatever judges fancy is just (and there are only two choices—thumbs up or thumbs down).

On this basis, citizens can be rousted from their homes and kicked to the curb (and some are left destitute). On this basis, also, they may be entered into domestic violence registries (indefinitely), besides state and federal law enforcement databases (indefinitely), and denied security clearances, loans, leases, and even employment in certain fields (just like convicted felons).

Notwithstanding that restraining order allegations are introduced in civil court and aren’t subject to the criminal standard of evidence (“proof beyond a reasonable doubt”), “criminal penalties, such as fines and incarceration, will attach if a protection order is violated”—or is simply alleged to have been violated: arresting officers need only have a reasonable suspicion that a violation occurred, which they need not have witnessed.

The savvy observer will note that suspicion is the motive determiner of liability at all levels. Suspicion informs judicial disposition, subsequent police response to claims of violation, and of course interpretation by third parties, including employers (judges trust accusers, and everyone else trusts judges). Emphatically worthy of remark is that billions of dollars of federal monies have been invested over the past 20 years toward conditioning judicial and police suspicion.

The savvy observer will note that suspicion is the motive determiner of liability at all levels. Suspicion informs judicial disposition, subsequent police response to claims of violation, and of course interpretation by third parties, including employers (judges trust accusers, and everyone else trusts judges). Emphatically worthy of remark is that billions of dollars of federal monies have been invested over the past 20 years toward conditioning judicial and police suspicion.

This may incline the savvy observer to suspect the fix is in.

He or she should appreciate further that restraining orders are most commonly issued ex parte, which means accusers simply fill out a form and very briefly interview with a judge without defendants’ being present to contest the allegations and without their even being aware that they’ve been made. (Some courts even explicitly advise plaintiffs to rehearse their allegations so they can recite them as quickly as they would an order at a drive-thru.) Although most states mandate that a follow-up hearing be slated to give the accused an opportunity to controvert the allegations against them and receive an “unbiased” second opinion, follow-up hearings are held in the same court that prejudicially ruled against them in the first place: “We found you guilty. Go ahead and tell us why we screwed up. You have 15 minutes.” Because restraining order trials are civil proceedings, defendants aren’t provided with legal counsel. They’re nevertheless afforded only a few days (or a couple of weeks at the outside) to prepare a defense.

Returning to this post’s epigraph, here’s its author’s elaboration of the points it introduces (which apply irrespective of what a restraining order is called):

The concept of a “protection order” or a “TPO” is a curious one under the law. Unlike a criminal case, where the awesome power of the State is wielded against a private citizen, an action for a protection order allows one private citizen to invoke judicial authority directly against another private citizen.

The implications are staggering when one considers that a protection order allows individuals to trigger invisible force fields affecting the conduct, movement, speech, and legal rights of others.

Even more significant is the fact that Nevada law allows a person to obtain a protection order based upon only a brief ex parte application [as do most or all states’ laws].

From these concepts, questions immediately present themselves. Are protection orders being utilized in oppressive or unexpected ways? Are the factual scenarios involved similar to what the [legislature] envisioned them to be? Are courts utilizing protection order tools correctly? Are judges issuing ex parte orders that trample upon the rights of innocent people before a hearing is held to determine the validity of specific allegations? Is this area of the law an insufficiently regulated “wild frontier”?

From these concepts, questions immediately present themselves. Are protection orders being utilized in oppressive or unexpected ways? Are the factual scenarios involved similar to what the [legislature] envisioned them to be? Are courts utilizing protection order tools correctly? Are judges issuing ex parte orders that trample upon the rights of innocent people before a hearing is held to determine the validity of specific allegations? Is this area of the law an insufficiently regulated “wild frontier”?

Loyola Law School Prof. Aaron Caplan, in a 2013 law review article that cites the 2008 paper of Mr. Tommasino’s quoted in this post, says yes.

Many structural factors of civil harassment litigation lead to higher-than-usual risk of constitutional error. As with family law, civil harassment law has a way of encouraging some judges to dispense freewheeling, Solomonic justice according to their visions of proper behavior and the best interests of the parties. Judges’ legal instincts are not helped by the accelerated and abbreviated procedures required by the statutes. The parties are rarely represented by counsel, and ex parte orders are encouraged, which means courts may not hear the necessary facts and legal arguments. Very few civil harassment cases lead to appeals, let alone appeals with published opinions. As a result, civil harassment law tends to operate with a shortage of two things we ordinarily rely upon to ensure accurate decision-making by trial courts: the adversary system and appellate review.

The process essentially operates “in a vacuum”:

Harassment orders, when granted, are very rarely appealed. In the Justice Courts of Las Vegas in 2008, only three out of 2034 non-domestic violence petitions resulted in an appeal. No appellate court opinions interpret the Nevada statute—even though it was enacted in 1989 [that’s zero appellate court opinions in 20 years]. As a result, “the limited jurisdiction courts [of Nevada] have been operating in a vacuum and creating ad hoc, reactive solutions” to recurring problems.

The stagecoach, in other words, is steered without reins. The laxity of the statutes means judges of the lowest-tier courts call the shots, and there are no big brothers looking over their shoulders. They’re licensed to do what they want. (The quotations above refer to different types of restraining order, but the two types aren’t necessarily treated any differently. Whether a petitioned injunction is a protection order or a harassment order may only depend on which box was ticked on the application form. In most jurisdictions, what distinguishes one from the other is the nature of the relationship between the accuser and the accused. The allegations may be identical.)

The legislative insensitivity to constitutional principles and protections as well as the lack of judicial housekeeping in this area of law are beneath the perceptual threshold of the public. To the uninitiated, the absence of controversy originating from “legitimate” sectors suggests that everything’s working as it should: restraining orders are issued to dangerous people who need to be tethered.

While how commonly the process is exploited for ulterior motives is a matter of heated dispute, its availability for abuse is plain. The prevailing attitude toward allegations of rampant abuse is that if statistics can’t be adduced to support them, the complaint is irrelevant and should exercise no influence on policy reform. The absurdity of this attitude is likewise plain. The process is designed to favor accusers, judges are predisposed to credit accuser’s accounts (in part according to explicit instruction), those accounts need not be substantiated, the process is initiated and completed in hearings spanning minutes only, and (as the court attorney who wrote the epigraph notes) comprehensive statistical information about restraining orders is virtually non-existent.

While how commonly the process is exploited for ulterior motives is a matter of heated dispute, its availability for abuse is plain. The prevailing attitude toward allegations of rampant abuse is that if statistics can’t be adduced to support them, the complaint is irrelevant and should exercise no influence on policy reform. The absurdity of this attitude is likewise plain. The process is designed to favor accusers, judges are predisposed to credit accuser’s accounts (in part according to explicit instruction), those accounts need not be substantiated, the process is initiated and completed in hearings spanning minutes only, and (as the court attorney who wrote the epigraph notes) comprehensive statistical information about restraining orders is virtually non-existent.

The restraining order process is conducted in a black hole. There’s not only no transparency; there’s no light.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

Reblogged this on .

LikeLike

I remember a while back I mentioned the concept of “breaking the chain.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breaking_the_chain

Basically, all you need to do is figure out what the prejudice of the judge was (how the judge was negligent). And then you can get a re-hearing. The evidence of the judge’s negligence, post-“res judicata” would enable the petitioner/respondent to get a re-hearing.

LikeLike

It’s great of you to bring these tactics to light.

The trick is making arguments like this without an attorney’s help. The fact is unless a litigant is prepared to take a case to the state court of appeals if valid arguments s/he makes are discounted or illegitimately blown off by the trial judge, what that judge says (according to whim) goes. This kind of effort is daunting (and costly), and it’s made all the more daunting by defendants’ having had it repeatedly confirmed to them that resistance is futile.

I’ll investigate, though. Just getting these ideas out there may be of value. Making them practicable is harder.

LikeLike

Well, what I said is probable to key to over-turning your restraining case you had with the blonde. Didn’t the judge act arrogant in his prior case saying that his courtroom was the last bastion of civilization? Hmm. I noticed that the Arizona courts seem to have a pay-to-play docket. To “falsify the judge,” you’d have to go through case law (post-res judicata) and see where the judge made an error (perhaps even illegally covered it up). By focusing on the judge, you can obtain a re-hearing. Otherwise, just focusing on what-ever case law involves comparing and contrasting various cases around the state and county in an attempt to refute the judge’s reasonableness.

LikeLike

God knows if anything can be revisited this many years later. I’ve been in and out of court for over eight years—and talked to multiple attorneys about the case.

Yeah, Arizona courts are still very much wild, wild west. Humorously, the court is okay with deeming someone a “danger” while still being reluctant to deny them the right to own a gun unless they’ve explicitly threatened to use one. (You can encounter people wearing guns on their hips here in convenience stores and supermarkets—and we’ve passed laws in recent years making concealed carry and packing heat in a bar legal without a license.)

All judges of restraining orders surely err. Respondents (total strangers to the court) are heard for a handful of minutes, and judges (in my experience) don’t probe the issues (or even ask questions). Certainly a case for prejudice could be made. The court does presume plaintiffs are telling the truth (and does presumptively distrust defendants). The only basis, really, for giving a judge pause in following a predetermined trajectory is a job title. There isn’t sufficient time for character impressions except of the most superficial nature (appearance, facial expression, etc.). The “last bastion of civilization” pronouncement was actually inspired by the conduct of one of the accusers (which I didn’t observe). I’m not sure pomposity from judges isn’t what most people expect, though. It’s certainly what I expect. I did (and possibly still do) have a basis to request a new trial. I’m just tired, and another disappointment might tip me over the edge. There’s only so much indignity a person can tolerate.

Thank you, though, for the considerate thoughts. They’re appreciated.

LikeLike

In the most recent trial, the weasel representing my accuser shot this at me: “She says you propositioned her” (that is, I was supposed to have “sexually solicited” her). Predictably no specifics were given. I should have pushed for some, but no amount of preparation can guarantee you the poise to respond to this kind of trash when you’re rabbit-punched with it.

The judge didn’t even arch an eyebrow. The court’s willingness to abet and dignify this kind of scat is disgusting (and, of course, confirms to a reasoning mind that neither honorable conduct nor fairness can be expected). Unscrupulous accusers and attorneys know they can just make up whatever they want (and judges just make up whatever they want).

Label a man a brute, sexual aggressor, or even a rapist…meh. Criminally profile him and stick his name in police registries…meh.

By contrast, I read the other day that a Kansas woman won a $1,000,000 defamation suit against a radio station that said she was a porn star.

LikeLike

Excellent scholarly material, Todd. If you’re not a lawyer, you should be.

And coincidentally, today I have been delving into the same area of Professor Caplan’s legal excellence relating to the disparity of justice between plaintiffs and defendants in this troubling area of the law. And here is what I wrote. It even attracted a loony troll into the thread:

https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/alt.appalachian/ZlezEe8CDHc

Matter of fact I plagiarized some of my own material — a recent comment in your weblog, which is a precious service to the men and women in the USA who have been oppressed by the epidemic of frivolous restraining orders and the creeps in robes who issue them.

LikeLike

Thanks, Larry. Sorry about your heckler. That’s the nice thing about this forum: tools for filtering spammers and flamers. It makes me angry that someone with your credentials and intellect has to tolerate further indignities writing about indignities and inequities that already glare.

I’ll be putting up a post about class actions today. FYI. Maybe it’ll inspire somebody.

LikeLike