This post, published on the first day of the year, was updated on July 9, 2018 (reflected in the new title), and content that had been unlawfully censored by the court has been restored. A recent respondent to this blog commented, “I think these injunctions violate the Constitution.” Despite the baggy parameters dictated by the law, it’s certain that many are impeachable as unconstitutional. The saga that follows relates the story of such an injunction. Readers merely interested in learning what unscrupulous plaintiffs can get away with (again and again for years) may skip the preamble and gain a clear picture by contrasting various sworn and unsworn statements by two such plaintiffs, who are quoted verbatim. Other quotations show how a witness, Michael Honeycutt, was induced to give misleading testimony, besides how willing attorneys may be to steer the court amiss…for the right price.

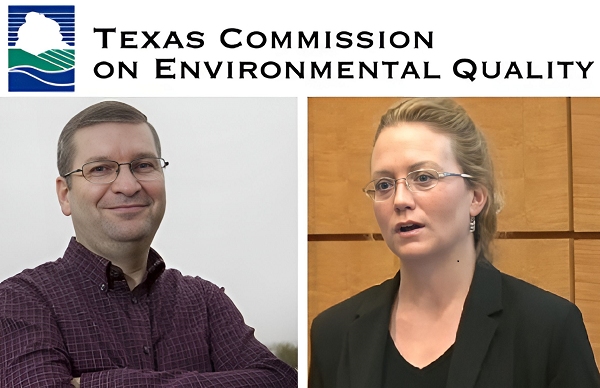

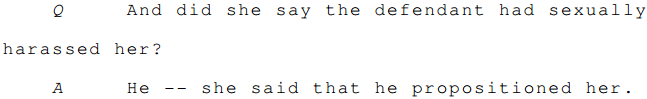

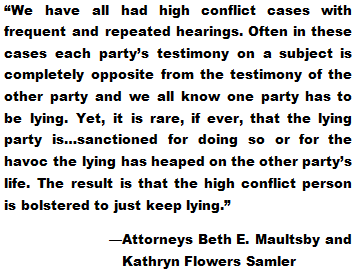

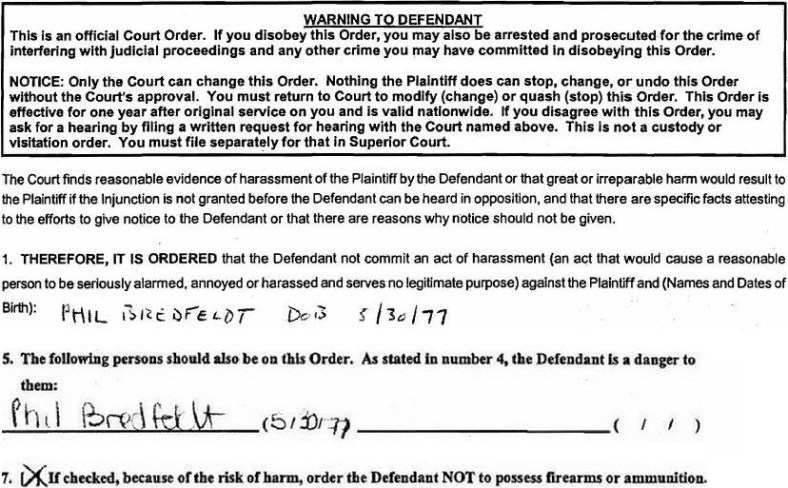

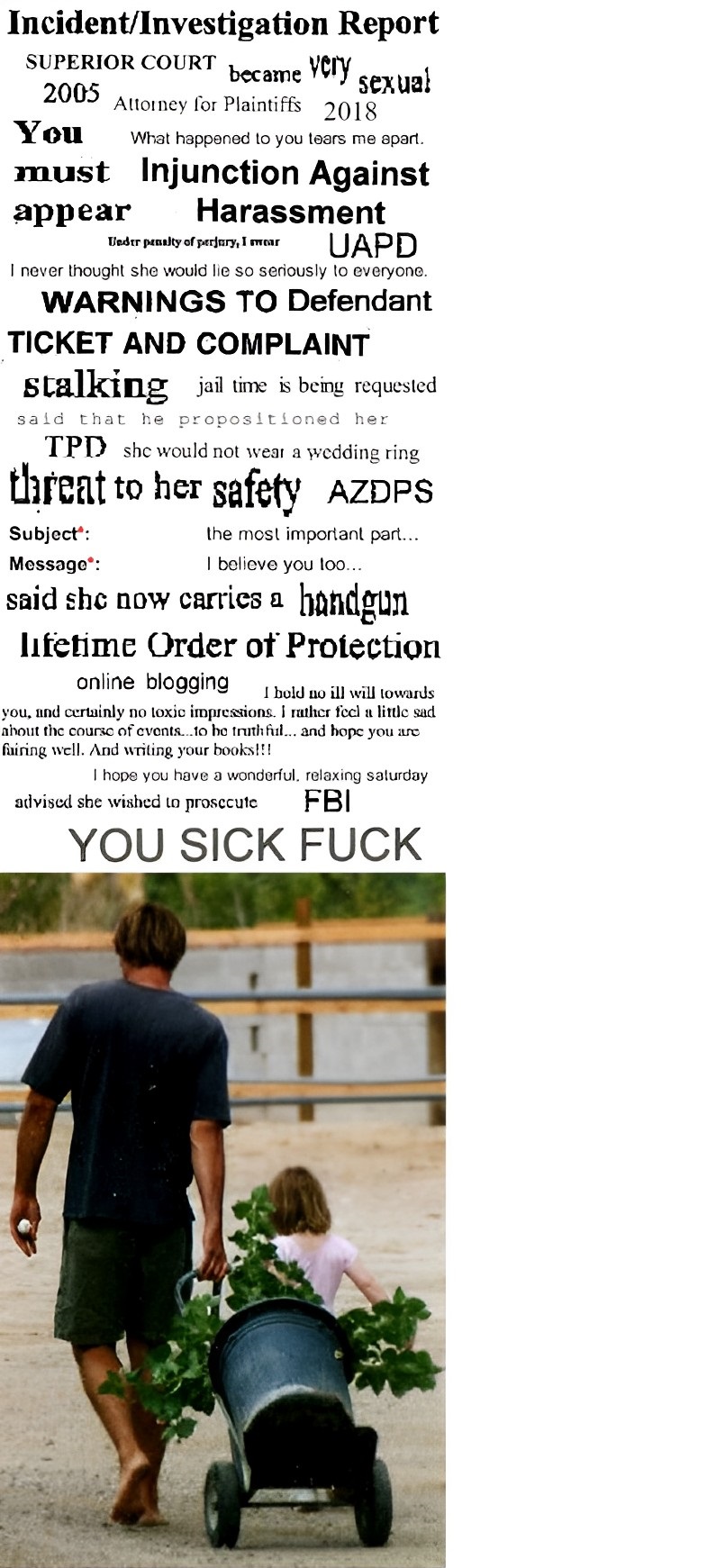

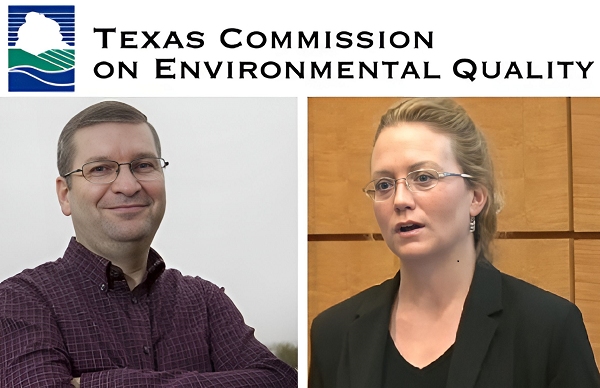

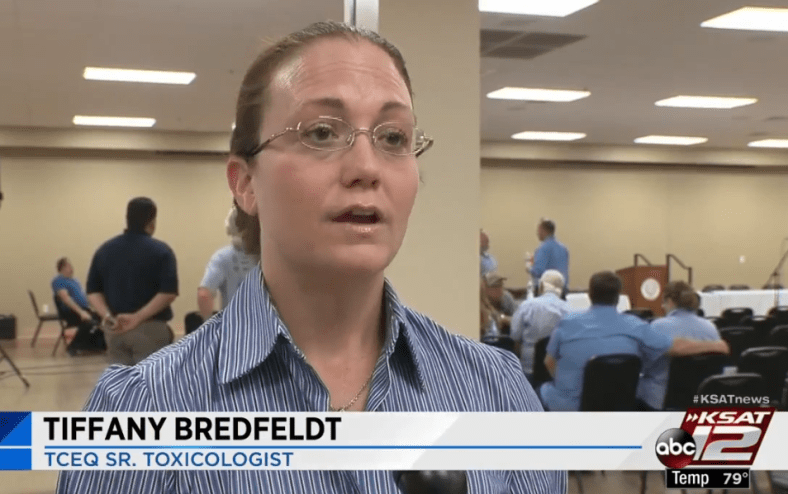

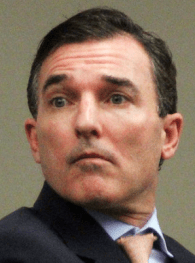

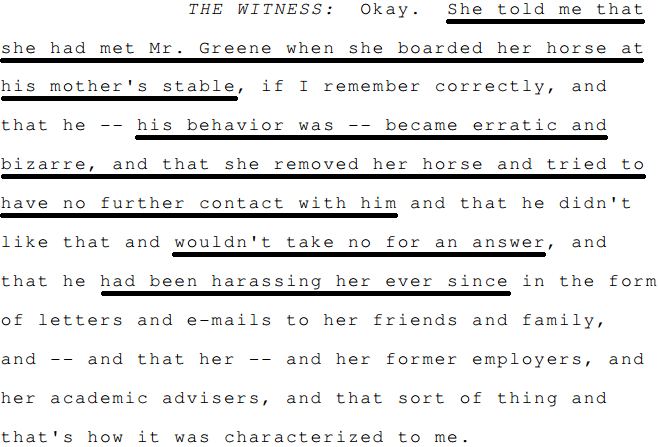

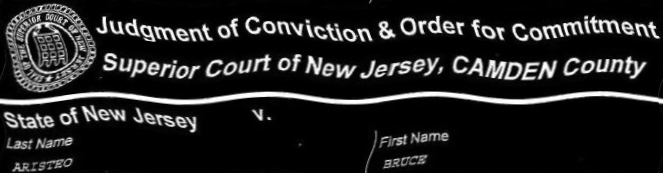

Texas state toxicologists and newly appointed EPA reps Michael Honeycutt and Tiffany Bredfeldt gave testimony before an Arizona Superior Court judge in 2013 that succeeded in persuading the judge to issue an unconstitutional speech injunction against the writer. The court was told the writer had “propositioned” Bredfeldt (a married woman) in 2005, “wouldn’t take no for an answer,” and “had been harassing her ever since.” Honeycutt, who has never met the writer, recited this secondhand story with the same smug complacency that marks his expression above. Based on the fiction’s effectiveness, four additional legal actions were brought against the writer in 2016, two of which menaced him with the threat of incarceration for exercising his freedom of speech. One of the actions was aborted; two were dismissed. Despite an appeal in 2017, the 2013 gag order, which the writer was alleged in 2016 to have “continuously and contemptuously violated,” remained in effect until July 2018, when it was gutted. All charges brought against the writer in the past decade have been invalidated.

Numerous accounts related on this blog since its launch six years ago have contrasted what he said with what she said in testimony given under penalty of perjury. The account this post relates doesn’t have to. It contrasts what she said here with what she said there—and with what her statured witness said she said. Statements that should harmonize, conflict.

A lesson of what this post unfolds, valuable for anybody to learn who has been wronged by a judge and isn’t sure if s/he’s “allowed” to talk about it, is that when people get away with something in a courtroom, which is a public forum, that in no way immunizes them from being exposed for it in a different public forum (for example, Facebook, Twitter, a personal blog, or one sponsored by The Washington Post). The only legal surety against criticism in this country is square conduct. While a court can lawfully issue a restraining order that prohibits unwanted speech to someone (like phone calls or emails), it cannot lawfully prohibit unwanted speech about anyone. Critical speech directed to the world at large, however objectionable it may be to those it names, whether private individuals, public officials, or judges, is protected speech as long as it isn’t false or threatening (and opinions are sacrosanct); the Constitution doesn’t favor any citizen over another, nor does it distinguish between bloggers, pamphleteers, or picketers and the institutional press. The aegis of the First Amendment doesn’t even require that criticism be deserved. In this instance, however, blamelessness is a nonissue.

This post discredits a widely championed arena of law, as well as how it’s administered. Linked audio clips of one trial judge will make a seasoned courtroom veteran flinch; those of another, a presiding municipal court magistrate, acknowledge frankly that restraining orders “are abused,” no question, and that “people come in and…say things that are just blatantly false” but are “never…charge[d],” let alone prosecuted.

This post discredits a widely championed arena of law, as well as how it’s administered. Linked audio clips of one trial judge will make a seasoned courtroom veteran flinch; those of another, a presiding municipal court magistrate, acknowledge frankly that restraining orders “are abused,” no question, and that “people come in and…say things that are just blatantly false” but are “never…charge[d],” let alone prosecuted.

The post also discredits accusations made by a woman (women, in fact) against a man. To some, this will be its most compelling virtue. Men have traditionally been the butt of abused and abusive procedures, and by far continue to be their most populous feedstock. Assertions that men are “presumed guilty” and unfairly “demonized” are not exaggerations and never have been, contrary to the pajama punditry of demagogues like David Futrelle, Mari Brighe, Amanda Marcotte, and Lindy West, who would smother even the most righteous motives for male contempt beneath the blanket label “misogynist.”

Fixation on gender politics, though, has obscured from view that injustice has been legislated into the law and fortified by decades of accustomed application (albeit that politics is the reason why). Today women—straight, gay, or otherwise—enjoy no greater safety from accusation and arbitrary violations of their civil rights than men do (in drive-thru procedures promoted as “female-empowering”), and women too may be accused by women (including their own mothers, sisters, daughters, and neighbors—which is a predictable consequence when accusation is tolerated as a recreational sport). Law that mocks due process and facilitates and rewards its own abuse is iniquitous, period. What this post reveals, importantly and inescapably, is that how many people choose to understand accusation, court process, and their repercussions is deplorably simplistic. Among these many are most politicians, academics, journalists, and social justice activists.

The Tucson man in the title of the post is also its author, and there was a time, within his memory, when to allege sexual impropriety without urgent grounds would have stirred outrage, because such an accusation is always damaging. In the climate that has prevailed since the advent of the Violence Against Women Act, however, the female plaintiff who doesn’t allege sexual violation, or at least trespass, squanders invaluable leverage. To a potently shrill sector of the community, this represents social progress. It has made pollution de rigueur.

The Tucson man in the title of the post is also its author, and there was a time, within his memory, when to allege sexual impropriety without urgent grounds would have stirred outrage, because such an accusation is always damaging. In the climate that has prevailed since the advent of the Violence Against Women Act, however, the female plaintiff who doesn’t allege sexual violation, or at least trespass, squanders invaluable leverage. To a potently shrill sector of the community, this represents social progress. It has made pollution de rigueur.

Inaugurating the task of restoring a site inspired by the tenacity of false accusations like those exposed below, this post breaks a year-and-a-half-long silence coerced from the site’s owner by a series of lawsuits, which included two that demanded that he be jailed for exercising his First Amendment rights. The principal complainant, Tiffany Bredfeldt, an official at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), has repeatedly alleged to the Arizona Superior Court that the writer’s criticisms of her honesty, ethics, and character are untrue. Bredfeldt told the court in 2016 that the “ongoing fear, stress, and associated physical impacts” the writer’s criticisms had caused her “have been a decision factor as to whether or not [she has] children.” She also reported she has “talked to more people at police departments, sheriffs’ departments, and federal and state agencies than [she] can count,” and urged the court to impose “significant consequences” to bring her relief from a “continual rollercoaster of fear.”

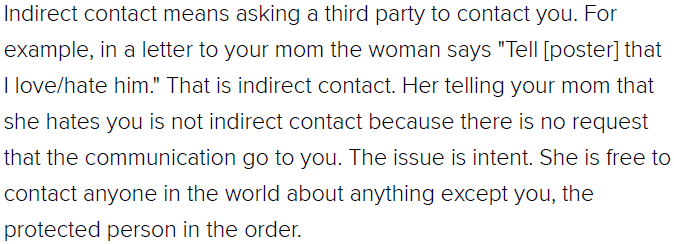

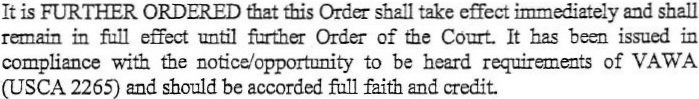

“I am not going to hold him in contempt for talking about his case,” Pima County Superior Court Judge Richard Gordon pronounced in response to a 2016 complaint that demanded the writer be jailed for doing exactly that. Also commendably, the judge granted the writer a court-appointed attorney without reservation. Disagreeing, however, that the law authorized him to revise or dissolve an illegal prior restraint entered against the writer in 2013, the judge instead delimited its vague and overbroad proscriptions. The writer continued to be (1) forbidden from publishing images of the plaintiffs on this site; (2) forbidden from using “[meta] tags” with their names to label images or contents of posts, supposedly elevating them in Google’s returns for certain search terms thereby; (3) forbidden from “repeating” three “specific statements” that, absent a jury opinion, the 2013 court deemed “defamatory”—only two of which the writer may have made, both concerning honesty; and (4) forbidden from contacting the plaintiffs, Tiffany and Phil Bredfeldt, the former’s employers at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, or “their friends, their acquaintances, or their family.” The writer’s own friends and family are among Tiffany Bredfeldt’s acquaintances, and who else may be is impossible for the writer to know, which underscores the recklessness of the 2013 order Judge Gordon construed rather than vacated. That order’s prohibitions, which were substantially narrowed in July of this year, could have been interpreted very differently by another judge at any time for the rest of the writer’s life.

Bredfeldt sued the writer in 2013, neither for the first time nor the last. Michael Honeycutt, to whom the writer had communicated his criticisms of Bredfeldt’s conduct by letter two years before, served her as a witness—telephonically, from the comfort of his desk chair in Texas. Honeycutt is Bredfeldt’s boss at the TCEQ and an old hand at testifying; his bio [deleted from the Internet since this publication] boasts that he has testified before Congress. His role in accusing the writer, who in 2013 had already grappled with crippling allegations for seven years, was to ensure that he would live with them indefinitely—and it’s unlikely that Honeycutt acted without the full approval and support of the TCEQ’s administration.

The upshot of the 2013 prosecution, in which the writer represented himself, was that Bredfeldt was granted an unconstitutional restraining order that prohibited the writer from publishing anything about her “to anybody, in any way, oral, written or web-based” by the judge whose words appear a few times in the transcript excerpts that follow. That Pima County Superior Court judge, Carmine Cornelio, is a judge no longer. In June of 2016, 84% of an Arizona Commission on Judicial Performance Review panel concluded he did not meet standards. The judge declined to face voters that fall, and his tenure on the bench terminated two months later.

(The no-confidence rating returned against Judge Cornelio in 2016 followed reprimands by the Arizona Supreme Court in 2010 and 2013 for the judge’s saying “fuck you” to an attorney during a settlement conference, causing a 19-year-old girl to cry during a different one, and gesturing accusatorily at a female court employee in public, among other alleged acts of “abusive conduct.” In a guest column in the Arizona Daily Star, Judge Cornelio wrote, “I leave with head held high….” He told the same paper in an interview that he “intends to go into private practice in alternative dispute resolution.” Judges of the Arizona Superior Court are paid $145,000 a year, and a proposal has been tabled to raise their salaries to $160,000.)

The speech injunction Judge Cornelio imposed on this writer in 2013, which the judge made permanent without bothering with a trial, was affirmed in 2016 by a second Pima County Superior Court judge, Richard Gordon, despite Judge Gordon’s having acknowledged in open court that the conduct of the 2013 proceedings was “not legal” and that the prior restraint that issued from them offended the Constitution. “There are obviously some parts that are just too broad and then don’t make a whole lot of sense,” Judge Gordon conceded in court in July. In his subsequent Sept. 2016 ruling, little trace of this acknowledgment survives. The writer’s father died a month after the ruling was returned. More than a year has transpired since (and, as the U.S. Supreme Court has held, “[t]he loss of First Amendment freedoms, for even minimal periods of time, unquestionably constitutes irreparable injury”).

An appeal of the 2016 ruling to the Arizona Court of Appeals’ Second Division was denied in December (five months after it was filed). The court—consisting of Judge Philip Espinosa, Judge Christopher Staring, and Judge Sean Brearcliffe—declined to address the prior restraint’s unconstitutionality and sidestepped use of the phrase prior restraint entirely:

[T]he issue before us is not whether the injunction is constitutionally permissible, but whether the [2016] trial court properly refused to modify or dissolve it.

The appeals court, whose decision may have been influenced by a case narrative that this post will show is false, did acknowledge that “[a]t least one provision of the [2013] injunction would appear clearly unconstitutional, ordering that ‘[t]he defendant…immediately cease and desist all future publications on his website or otherwise.’” The word publication means any act of public speech. This provision, which was dissolved in July of this year, accordingly prohibited the writer from, for example, finishing a Ph.D., addressing the city council, marketing a book, or defending himself in a courtroom, all of which require publication. Also accordingly, courts have consistently found prior restraints facially invalid, even ones far less vague and overbroad than the one issued against the writer, and such orders have been vacated as much as 30 years later, which the writer’s attorney informed the appellate judges by brief and in oral argument. This was unremarked in their Dec. 18, 2017 ruling.

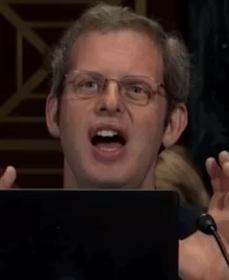

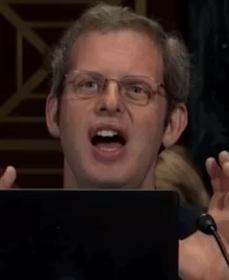

UCLA Law Prof. Eugene Volokh, addressing the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee on June 20

Unlike in 2013 (and previously), the writer wasn’t alone in court in 2016 or 2017. His defense was aided by two gifted lawyers representing the Pima County Legal Defender: Kristine Alger, who drafted and orally augmented a faultless appeal, and Kent F. Davis, whose zealous advocacy made an appeal possible in the first place. Their arguments were what’s more reinforced by no lesser light than Eugene Volokh, who’s distinguished as one of the country’s foremost authorities on First Amendment law and who, in conjunction with the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and Phoenix attorney Eric M. Fraser, graciously submitted an amicus brief to the court on the writer’s behalf. Alison Boaz of the UCLA School of Law, who assisted Prof. Volokh, is also due credit. A win in the appellate court would have been much more theirs than this writer’s, and they have the writer’s thanks for their Herculean exertions.

(It’s conceivable that a legal critique of the matter may one day appear on The Volokh Conspiracy, which is listed by the ABA Journal in its “Blawg 100 Hall of Fame.”)

Exemplifying the importance of the First Amendment, this post will illuminate how trial courts are manipulated into forming bad conclusions by lowering its beam into the crevices to rest on those who do the manipulating.

A byproduct of the writer’s representation in 2016 and 2017 was access to courtroom transcripts, so the post won’t offer much in the way of opinion. Commentary can be denied. Testimony given under oath…cannot be.

—Dr. Tiffany Bredfeldt, on cross-examination by the writer in 2013

—Dr. Michael Honeycutt, on cross-examination by the writer in 2013

Based on nothing more than the two statements quoted above, a precocious child would wrinkle her nose. Yet such obvious contradictions have inspired no judge to arch an eyebrow nor any Ph.D. to scruple. In over 11 years.

Calling someone a liar risks being sued, and trial judges interpret whatever they want however they want. They’re acutely aware, moreover, of which direction their criteria are supposed to skew when abuse is alleged. This remark cannot be called defamatory: Although this post isn’t about air or water pollution, as would befit one that quotes environmental scientists, it does concern filth.

Director of the Texas A&M Health Science Center Institute of Biosciences and Technology Cheryl Lyn Walker, remarks by whom were used in evidence against the writer in 2013 and 2016

It relates sworn testimony to the Arizona Superior Court by two representatives of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), reportedly the second largest agency of its kind after the EPA. Those public sector scientists are Michael Honeycutt, Ph.D., the TCEQ’s toxicology director and an adjunct professor at Texas A&M University, who was recently entrusted with a role in forming national health policy, and one of Honeycutt’s protégés, senior toxicologist Tiffany Bredfeldt, who’s also a Ph.D. and who had already been entrusted with a role in forming national health policy. On April 4, 2017, the TCEQ tweeted its congratulations to Bredfeldt for her being selected to serve on the Chemical Assessment Advisory Committee of the EPA’s Science Advisory Board, which her boss now chairs. The bio of Bredfeldt’s associated with her appointment highlights her experience as an “expert witness.” This merits note, as does Honeycutt’s superior claim to the same distinction.

A second Texas A&M professor, Dr. Cheryl Lyn Walker, Ph.D., who was Bredfeldt’s postdoc adviser at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, has been aware of the conduct of Bredfeldt’s detailed in this post for a decade. Appeals by this writer to Walker’s conscience and integrity only inspired her to tell Bredfeldt in a 2008 email: “I am very concerned about your safety.” Bredfeldt entered Walker’s email in evidence against the writer in 2013 and also quoted it to the court in 2016.

Authorial intrusions in the survey of statements to follow will be terse. Bredfeldt and her witnesses will do the preponderant storytelling.

Tiffany Bredfeldt, romancing the camera in 2005

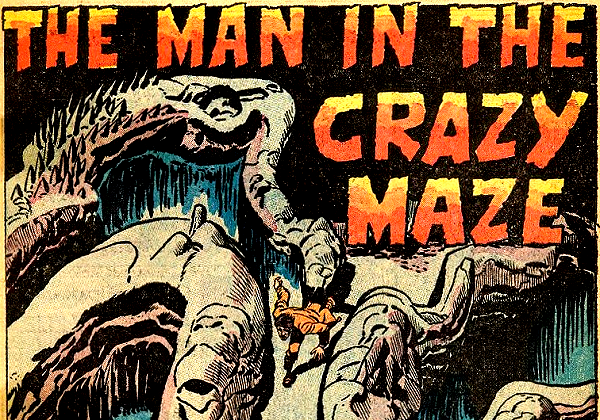

Some orienting details are required. The writer encountered Bredfeldt, then a doctoral student in the University of Arizona College of Pharmacy, at his home in late summer 2005 and met with her there routinely over the ensuing months, mostly after dark. Bredfeldt, otherwise a stranger, declined to mention to the writer that she was married while, for example, taunting him for not inviting her in at midnight: “Where I come from, it’s considered rude not to at least invite a person onto your porch.” Then she disappeared, providing no explanation. A few months after that, when the writer sought one, Bredfeldt variously reported to the police and numerous courts—in statements that remain public in perpetuity and that are not deemed defamatory—that the writer had made unwelcome sexual advances toward her, despite being repeatedly “rebuff[ed]” and “rebuked”; that he posed a violent danger to her and to assorted others she was concerned the writer would talk to about her conduct at his home (among them her mother, who lived 1,200 miles away); that he should be prohibited from possessing firearms; and that he had stalked her, a woman the writer had only ever met hanging around his yard like a stray cat.

Here’s Bredfeldt’s account in her own words to Judge Jack Peyton on April 10, 2006:

Okay, I’ll begin by defining my relationship, um, with Mr. Greene. I met Mr. Greene in about September or October of 2005 when I was boarding a horse that I own at a boarding facility owned by his family. At that time, uh, we were acquaintances, and we spent time talking and — at his family barn. And that’s about the nature of our — our interaction. During that time, I think, um, he developed maybe romantic feelings for me that — that made me uncomfortable, and I generally would rebuff his advances, asking him to stop.

Mrs. Bredfeldt, whom the writer knew for three months and with whom he has had no contact since March 2006, has along with one of two or three girlfriends of hers who were also routinely around the writer’s residence in 2005 sued the writer some six times. Four legal actions were brought against the writer in 2016 alone, two of which sought his incarceration and all of which endeavored to suppress what this post relates. In a “Victim’s Impact Statement” Bredfeldt submitted to the court in 2016, she owned that she had accused the writer “to the Court multiple times [and] to multiple police departments, detectives, federal agencies, and other officials in several states”—including the Arizona Dept. of Public Safety and the FBI—and it’s this writer’s belief that only with the blind support of loyalists like Mike Honeycutt would Bredfeldt have been so emboldened.

The legal onslaught has spanned (and consumed) almost 12 years, despite the writer’s appealing to dozens of people to look between the lines, including Honeycutt, who’s notably a husband with two college-aged sons. Honeycutt is besides a distinguished scientist, cited for his rigorous investigative standards, whose testimony quoted immediately below includes the statements, “I didn’t ask for details” and “I didn’t clarify that.” As a departmental director of the TCEQ, Honeycutt is paid $137,000 per. The writer, in contrast, has for the past decade earned a subsistence wage doing manual jobs that allow him to keep an insomniac’s hours and be left alone—formerly in the company of his dog, his dearest friend, who died suddenly in 2015 while the writer was still daily distracted with trying to clear his name and recover time and opportunities that had been stolen from them. (Here is a letter the writer hired an attorney to prepare in 2009. Bredfeldt represented it to the court in 2013 as evidence of harassment, and testified she believed her “psychiatric prognosis” would improve if such speech were restrained. “One of the most difficult parts of dealing with something, since this is profoundly stressful,” she told the court, “is that the stress doesn’t go away.”) The writer had aspired to be a commercial author of humor for kids, as Bredfeldt knew, and had labored toward realizing his ambition for many years before encountering her and her cronies on his doorstep. His manuscripts have since only gathered dust.

The legal onslaught has spanned (and consumed) almost 12 years, despite the writer’s appealing to dozens of people to look between the lines, including Honeycutt, who’s notably a husband with two college-aged sons. Honeycutt is besides a distinguished scientist, cited for his rigorous investigative standards, whose testimony quoted immediately below includes the statements, “I didn’t ask for details” and “I didn’t clarify that.” As a departmental director of the TCEQ, Honeycutt is paid $137,000 per. The writer, in contrast, has for the past decade earned a subsistence wage doing manual jobs that allow him to keep an insomniac’s hours and be left alone—formerly in the company of his dog, his dearest friend, who died suddenly in 2015 while the writer was still daily distracted with trying to clear his name and recover time and opportunities that had been stolen from them. (Here is a letter the writer hired an attorney to prepare in 2009. Bredfeldt represented it to the court in 2013 as evidence of harassment, and testified she believed her “psychiatric prognosis” would improve if such speech were restrained. “One of the most difficult parts of dealing with something, since this is profoundly stressful,” she told the court, “is that the stress doesn’t go away.”) The writer had aspired to be a commercial author of humor for kids, as Bredfeldt knew, and had labored toward realizing his ambition for many years before encountering her and her cronies on his doorstep. His manuscripts have since only gathered dust.

(A further counterpoint: The first public official the writer notified of Bredfeldt’s conduct, who also took no heed, was University of Arizona Dean of Pharmacy J. Lyle Bootman, Ph.D. A decade later, Bootman was charged with raping and beating an unconscious woman in his home. For almost two years following his indictment in 2015, while free on his own recognizance, Bootman faced trial—a fundamental due process right this writer was denied in 2013. Despite having been placed on administrative leave, Bootman continued to draw a faculty salary of over $250,000 from the U of A, the writer’s alma mater and former place of employ. As a graduate teaching assistant in the English Dept. in the late ’90s, the writer cleared about $200 a week. While he awaited a ruling in Greene v. Bredfeldt, the appeal of the last of the lawsuits brought against him during the same period of time by Bredfeldt and a cohort of hers, the five felony charges against Bootman were dropped. A tort case based on the same facts continues. Bootman’s attorneys filed for a protective order in December to bar public access to records.)

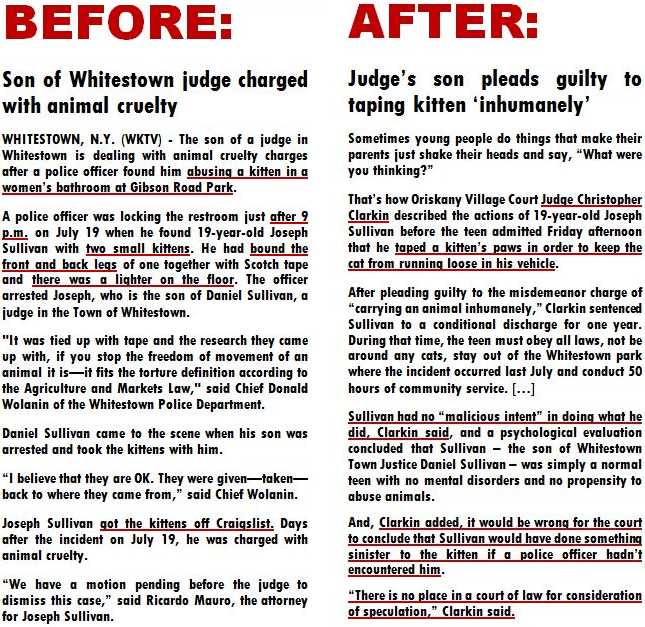

In an interview that aired in 2017, Tiffany Bredfeldt, the writer’s accuser, reassured the audience of ABC News that it could place its trust in the TCEQ. Bredfeldt made a similar pitch before the National Research Council of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in 2013. Bredfeldt, who the court was told in 2013 and 2016 is not a public official, has repeatedly appeared as the face of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. Her attorneys have argued that since she isn’t a public official, she isn’t obligated by law to prove her allegation that objectionable statements by this writer are false and therefore unprotected speech. Her boss, Michael Honeycutt, told the court in 2013: “Tiffany is just like the other 14 employees that I have.” If no other assertions by the TCEQ cause Texans concern, that one should.

This post’s presentation is simple: It juxtaposes contradictory statements that span seven years (2006–2013), most of them made under oath and all of them made by state scientists. (Those in small print may be enlarged in a new tab by clicking on them, or magnification of the entire post may be increased by pressing [CTRL] or [COMMAND, the cloverleaf-shaped key on Macs] + [+]. Zoom may be reversed similarly: [CTRL] or [COMMAND] + [-].) Scrutiny of the quotations below may lead the reader to conclude they’re evidence of false reporting, perjury, subornation of perjury, stalking, harassment, mobbing (including attorney-complicit abuse of process and civil conspiracy), defamation, bureaucratic negligence, professional incompetence, mental derangement, and/or general depravity.

The writer will let the facts speak for themselves.

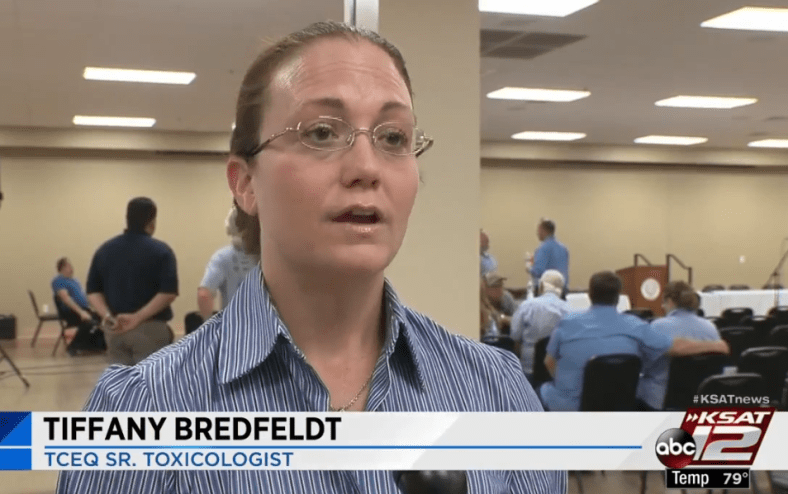

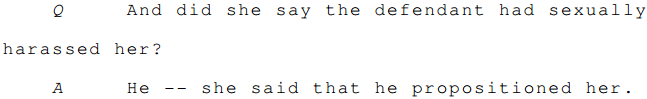

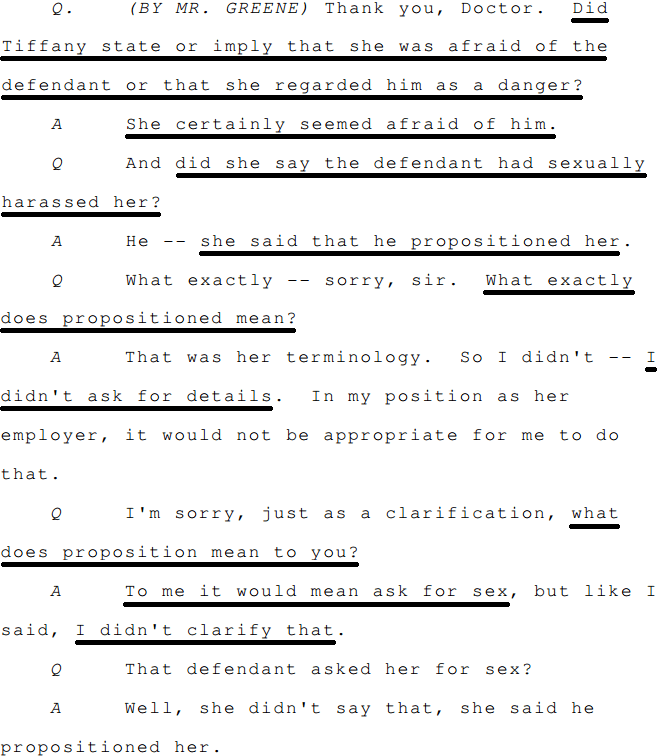

MICHAEL HONEYCUTT, on cross-examination by the writer on May 20, 2013:

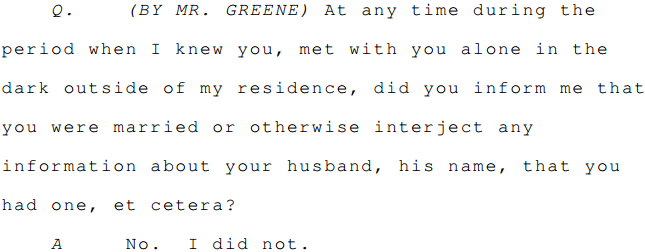

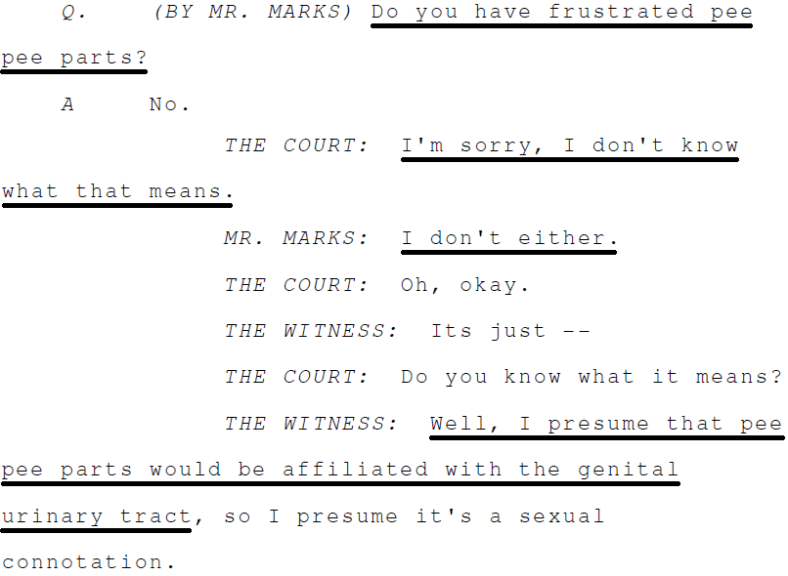

Honeycutt testifies in 2013 that Bredfeldt told him the writer “propositioned” her in 2005, which to him, he says, “would mean ask[ed] for sex.”

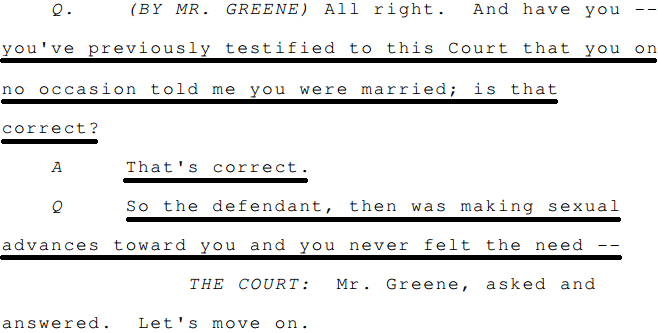

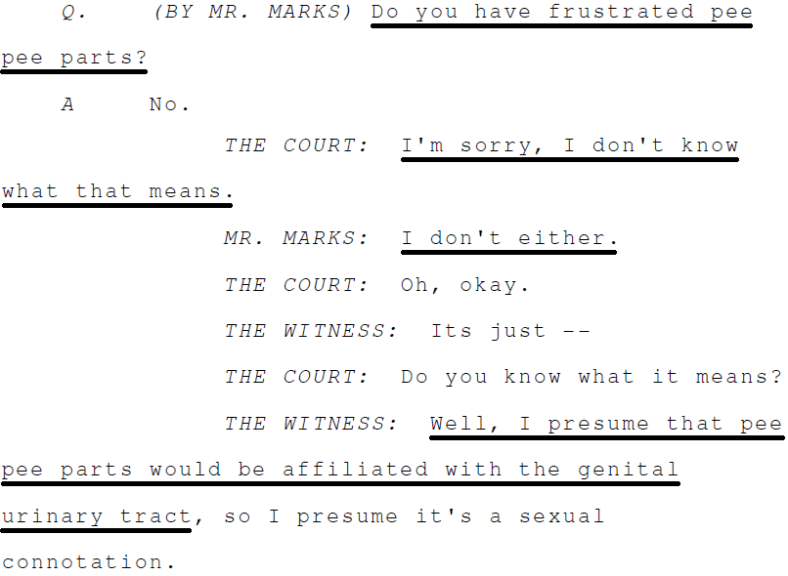

Bredfeldt’s attorney, Jeffrey Marks, would follow up on Honeycutt’s testimony by beginning his cross-examination of the writer with a jab instead of a question: “She says you propositioned her.” The writer replied, “What does that mean?” Marks chirped, “That you offered her sex.” Bredfeldt, while gazing around the room at her audience, nodded solemnly.

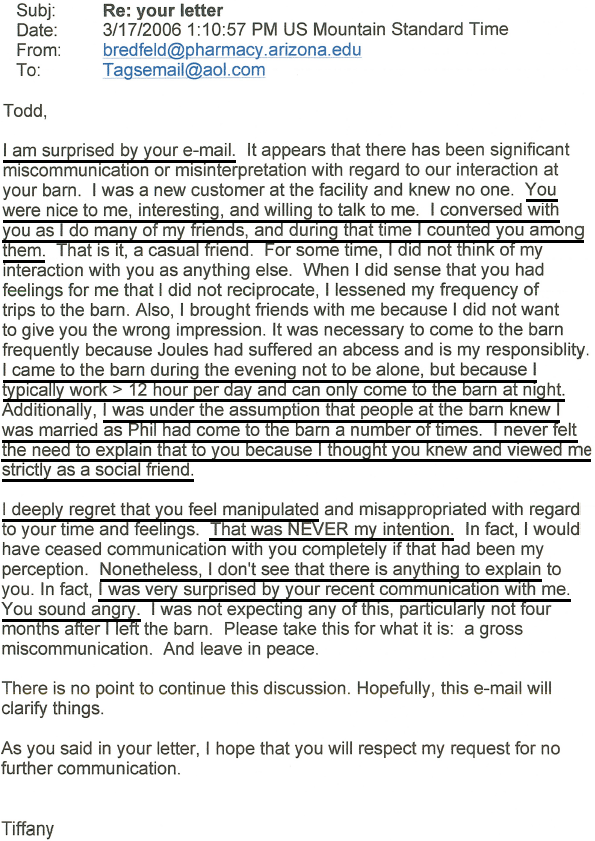

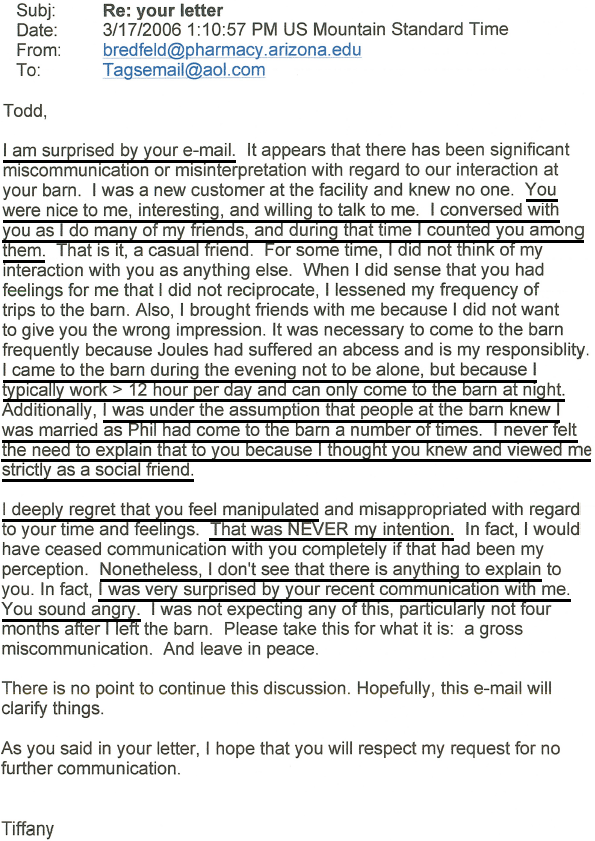

TIFFANY BREDFELDT, in an email to the writer sent Friday, March 17, 2006, that she entered into evidence three days later (Monday, March 20, 2006) along with her petition for restraining order number one:

Bredfeldt states in this self-contradictory email, which she would submit days later in evidence to the court in the 2006 procedure that began the controversy, that the writer had been “nice” to her and that she had “never felt the need” to “explain” to him she was married, because her husband had come to the writer’s place of residence “a number of times,” and she thought the writer already knew and besides “viewed [her] strictly as a social friend.” Contrast Honeycutt’s 2013 testimony: “[S]he said that he propositioned her.”

On April 10, 2006, not a month after Bredfeldt sent this email, she would testify before a judge (in her husband’s presence) that she had had to repeatedly “rebuff…advances” by the writer in 2005. The writer was identified to the court not as a considerate “friend” but as an “acquaintance” with whom Bredfeldt had “interact[ed].” Ten years later, the husband the writer was supposed to have known about, a geoscientist today employed by Weston Solutions as a project manager, would be asked in court on direct examination by his lawyer, “Do you know the defendant, Todd Greene?” Philip Bredfeldt’s answer: “I never met him….” Then Mr. Bredfeldt would clarify to the 2016 court that he “first came to know about the [writer] in early 2006,” that is, the same week his wife sent this email, during which the writer was alleged to have sent her a “series of disturbing emails” and “packages,” a fiction that by itself would take another entire post to unweave. Significantly, Phil Bredfeldt had no idea the writer existed until 2006 and, according to his 2016 testimony, was not informed by his wife of any sexual aggression toward her in 2005—nor was anybody else, for example, the writer’s mother, who was daily at the property where the writer lives from morning till dusk, and whom Bredfeldt knew and spoke with routinely. (The writer’s mother was then in treatment for cancer, a fact Bredfeldt exploited to flaunt her knowledge of the disease, which was a subject of her dissertation research.) Where Phil Bredfeldt was while his wife was outside of the writer’s residence at 1 a.m.—and with whom—has never been clarified.

Honeycutt, in a 2013 quotation below, will testify in further contrast to Bredfeldt’s statements in this email that he was told the writer’s behavior in 2005 was “erratic and bizarre” and that he “wouldn’t take no for an answer.”

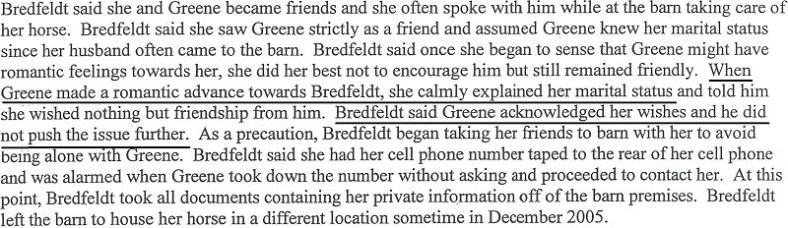

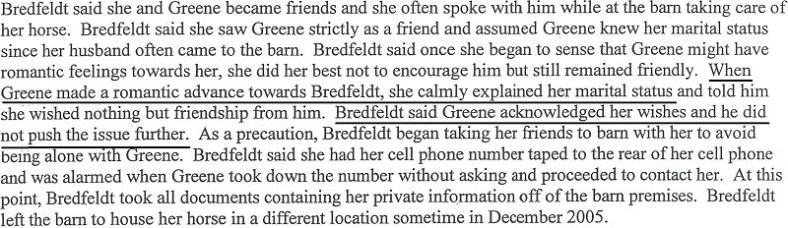

TIFFANY BREDFELDT, in a statement to the University of Arizona Police Dept. given on March 18, 2006 (the next day):

Bredfeldt, in contrast to her emailed statements to the writer 24 hours prior (and in contrast to her subsequent testimony to the court in 2006 and both hers and Honeycutt’s in 2013), reports to the police that the writer had made “a romantic advance” toward her in 2005, inspiring her to admit to him she was married, after which he desisted. Bredfeldt then says the writer seized her cell phone, copied down her number, and contacted her. Bredfeldt’s work and home addresses and telephone numbers were publicly listed, and the writer never spoke with Bredfeldt on the phone. There was no need; she could be found outside of his residence most nights, as often as not in a red tank top.

On the single occasion the writer had handled Bredfeldt’s cell phone, borrowing it because his phone had been destroyed by a power surge, Bredfeldt had insisted on typing the numbers for him before sliding the phone into his palm and caressing his fingers (repeatedly). That was in late Nov. 2005 after she and a friend of hers had invited themselves into the writer’s house. Bredfeldt’s “chaperone,” a stranger then calling herself Jenn Oas, began conversation by telling the writer she had just returned from India where she “mostly” hadn’t worn a bra. Bredfeldt chimed in with a quip about “granny panties” (after having excused herself and returned wearing freshly applied eye makeup, complaining that she had “misplaced” her glasses). A couple of weeks later, Bredfeldt would vanish.

(Flash-forward: The policewoman who instructed Bredfeldt how to obtain a court-ordered injunction, Bethany Wilson, is today a librarian in charge of kid lit—what the writer had aspired in 2006 to make his profession.)

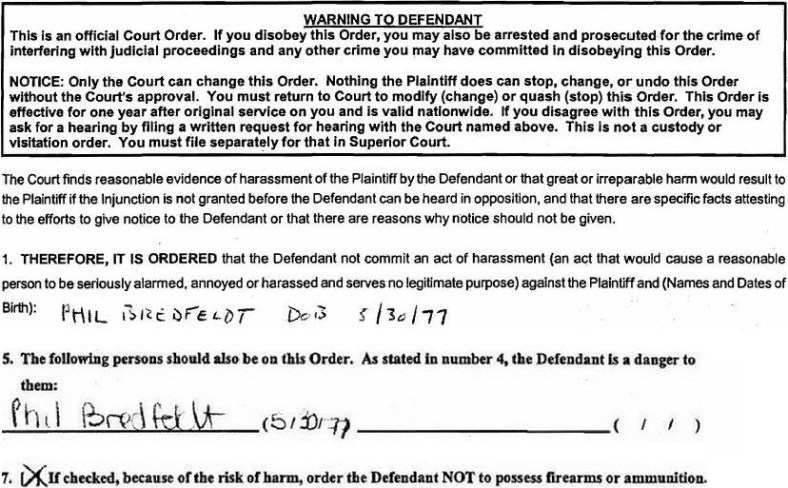

TIFFANY (AND PHIL) BREDFELDT, in a sworn affidavit to Judge Roger Duncan (then a pro tem) filed on March 20, 2006 (two days later):

Bredfeldt urgently petitions a protective order tailored to prohibit the writer (three days earlier called a “friend” who had been “nice” to her) from having any contact with her husband, Phil, a stranger, who is alleged to be in violent “danger.”

Later the same day, the writer would be sent an email, ostensibly by Phil Bredfeldt, that begins, “STAY THE HELL AWAY FROM MY WIFE, YOU SICK FUCK,” and ends, “THIS IS THE LAST TIME YOU WILL BE TOLD.”

(The Bredfeldts simultaneously sent the email to UAPD Officer Bethany Wilson, with whom she later told the writer they had been on the phone at the time. Officer Wilson, who had met both of them, opined during a 2006 interview with the writer that Mrs. Bredfeldt “wore the pants.”)

Judge Jack Peyton

The evidence of harassment Tiffany Bredfeldt presented to the court was five emails she and the writer had exchanged over a weekend (March 16–20): two from her, three from him in reply. The March 17 email of hers shown above was shuffled to the back of the sheaf, out of chronological order, causing the judge who presided over the writer’s April 10, 2006 hearing, Pima County Justice of the Peace Jack Peyton, to remark, “I don’t think I have a copy,” and then to ask, “Am I missing one [of the emails]?” Bredfeldt had to include the contradictory email among her evidence, which was never anyhow scrutinized, because it contained one of the only two requests she had ever made to the writer not to contact her: “I hope that you will respect my request for no further communication.” The other request was in an email she had sent him 20 hours earlier, in which Bredfeldt had represented the writer to himself as a stalker after he had gently tried to learn the motives for her behaviors at his home and her concealment from him that she was married. Judge Peyton confirmed with Bredfeldt that the minimum qualification demanded by the law, namely, two requests for no contact, had been met. The writer need not have been present.

Alleged on March 20 to be in danger of violent assault, Phil Bredfeldt had to be repeatedly reprimanded for displays of temper in open court three weeks later. Judge Peyton finally told him, after ordering his name stricken from his wife’s protective order:

I won’t think twice about asking you to leave the courtroom, because you’re not a party. You are welcome to be here. This is a public forum. But I won’t have you interrupting, and I will not have you making me uncomfortable about what your next action might be.

The judge, reputed to be the go-to JP for women alleging abuse by men, nevertheless cemented the protective order against the writer, explaining: “I do not get the impression that [Mr. Bredfeldt] was placed on that order by design.”

(The following year, Judge Peyton was appointed to head a county domestic violence specialty court, which was financed by a $350,000 gubernatorial grant that included no budgetary allowance for defense attorneys. The judge, a onetime Maryland labor lawyer d/b/a J. Craig Peyton, underwent a “five-day domestic violence training session” in preparation. Reportedly operating only two days a week, his court has since processed well upwards of 25,000 cases.)

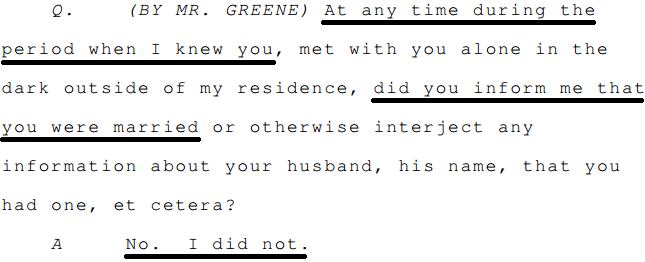

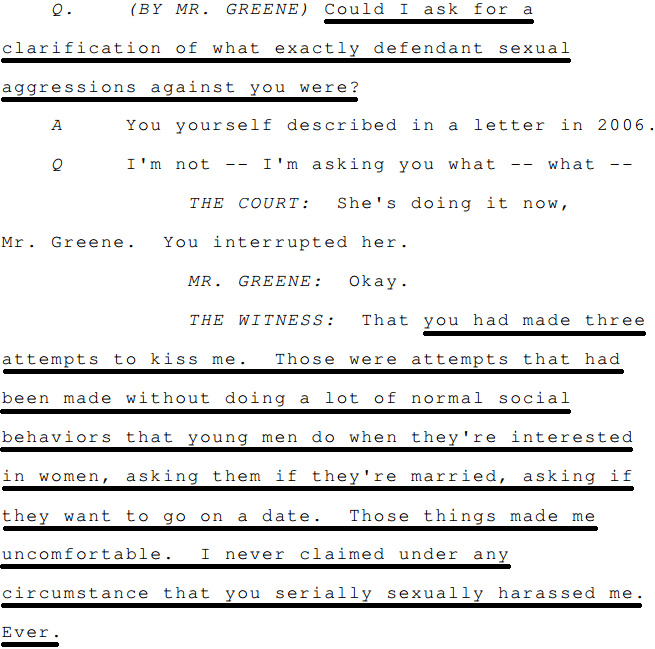

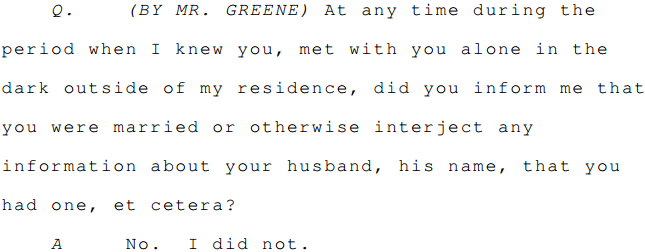

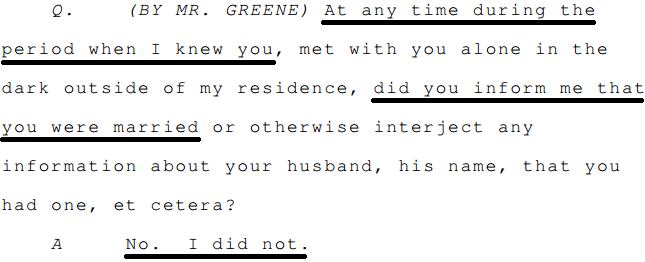

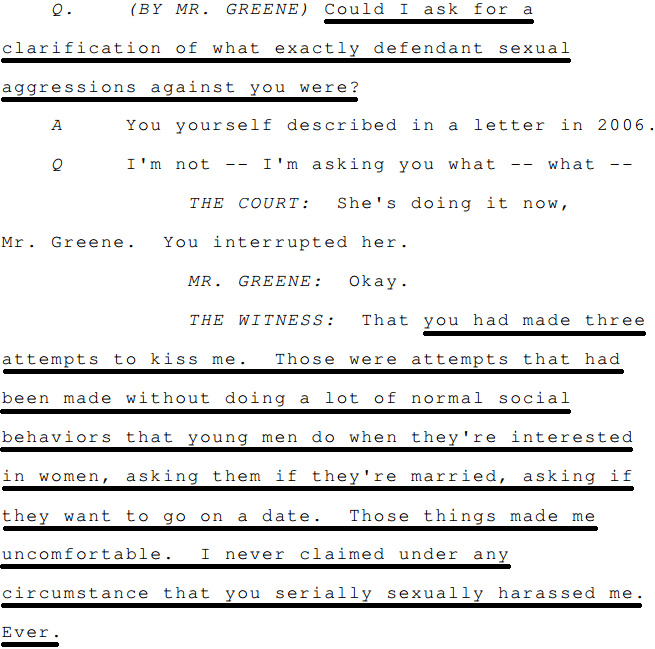

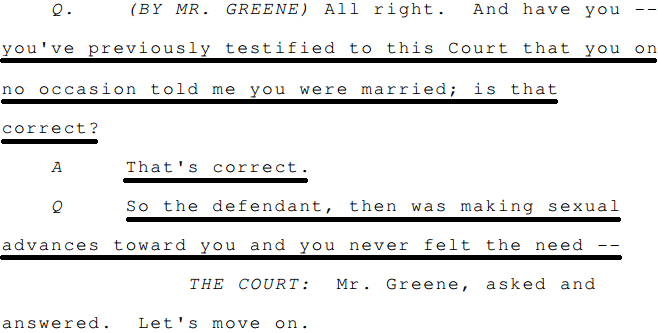

TIFFANY BREDFELDT, on cross-examination by the writer on May 20, 2013 (seven years later):

In contrast to her statements to the police in 2006, Bredfeldt testifies in 2013 that she never told the writer she was married. What Bredfeldt told the writer in 2005 was that she lived with a dog. The writer asked if it was alone at night while she was with him. Bredfeldt answered, “Yes.” The writer urged her to bring the dog with her so it wasn’t by itself and gave her a toy to take home.

TIFFANY BREDFELDT, on cross-examination by the writer on May 20, 2013 (the same afternoon):

Also contradicting her statements to the police in 2006 (besides controverting what her first witness, Honeycutt, told the court in 2013 that she had told him), Bredfeldt testifies (in the presence of her husband) that the writer made “three attempts to kiss [her]” in 2005—which made her “uncomfortable” but not so uncomfortable as to prompt her to tell the writer she was married (or to tell her husband that another man had repeatedly tried to kiss her). Then Bredfeldt denies she has “ever” accused the writer of sexual harassment.

TIFFANY BREDFELDT, in a memorandum to Superior Court Judge Charles Harrington filed July 30, 2006:

In a “Statement of Facts” to the court, contradicting her statements to the police (besides to the writer himself, which emailed statements she submitted to the court in 2006, 2013, and 2016), Bredfeldt alleges the writer made “several physical, romantic advances toward [her],” despite being “rebuked,” and that she was forced to flee “[w]hen such advances continued.”

There were no physical advances. Bredfeldt was invited to have Thanksgiving dinner with the writer’s family in 2005. Instead of telling the writer she had a husband to get home to, she said she was suffering from a migraine. The writer put his hand on her shoulder and said he hoped she felt better. All other physical contacts between Bredfeldt and the writer, clasps and caresses, were initiated by her, typically during conversations in which she pointedly referred to breasts, bras, or panties, her naked body, striptease, or the like. At the conclusion of an earlier meeting in November, Bredfeldt had thrust her face in the writer’s and wagged it back and forth as if to tease a kiss. The writer didn’t respond, because there was nothing romantic about it. That was on the night Bredfeldt returned after attending an out-of-state wedding—her sister-in-law’s (Sara Bredfeldt’s), a detail she omitted mentioning.

A month later, on the evening before Bredfeldt “left the horse boarding facility” (in 2005 not 2006), the writer encountered her loitering in the dark outside of his house—alone. Bredfeldt returned a coffeemaker she had borrowed from him to prepare poultices for her horse’s abscessed leg. During the transfer, Bredfeldt tried to brush the writer’s hands with hers. Bredfeldt and the writer spoke as usual—he remembers talking to her about shooting stars—and the writer’s mother briefly joined them and invited Bredfeldt to a Christmas party. Bredfeldt removed her horse the next day while the writer was at work.

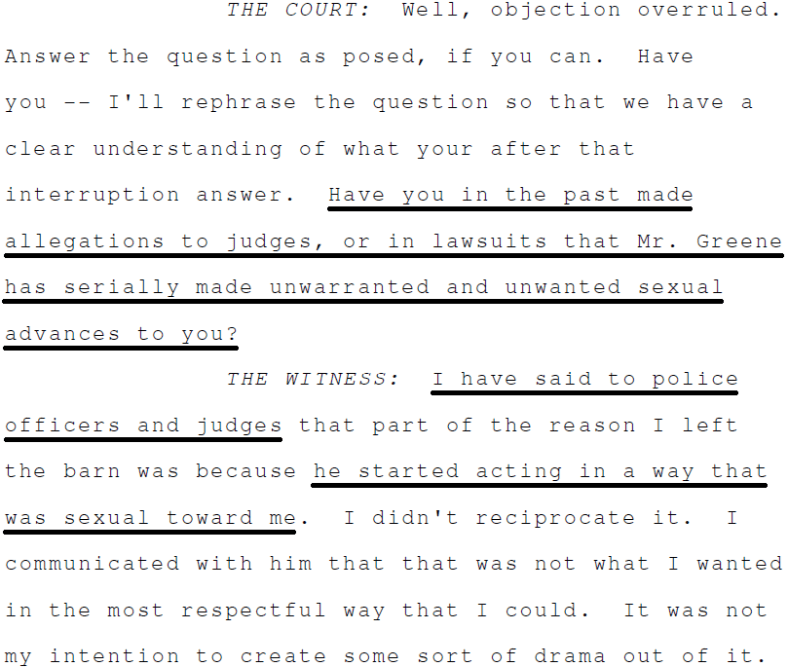

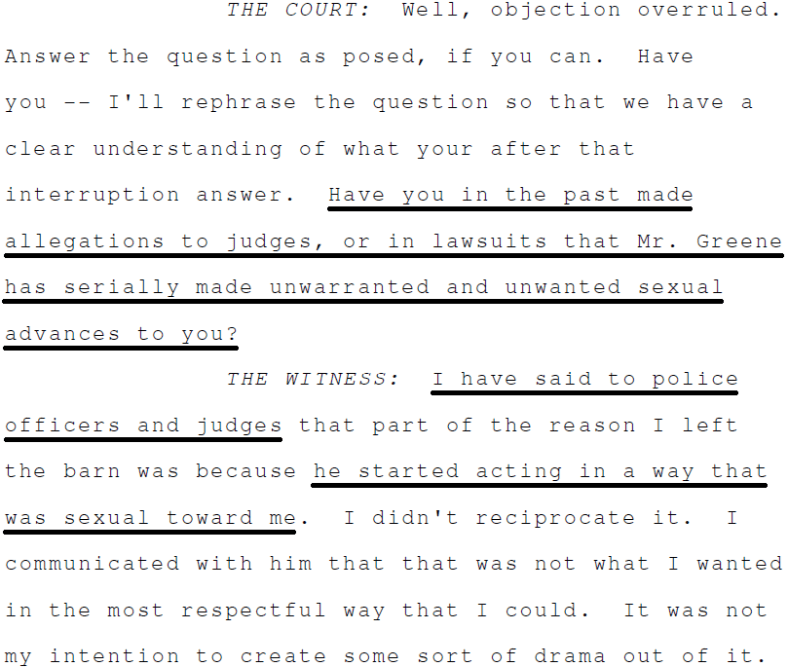

TIFFANY BREDFELDT, during cross-examination by the writer on May 20, 2013:

Bredfeldt testifies on examination by the judge that she has only ever told police officers and judges that the writer “act[ed] in a way that was sexual toward [her].” She “communicated with him that that was not what [she] wanted in the most respectful way that [she] could,” she says, which did not include either informing the writer she was married or wearing her wedding ring.

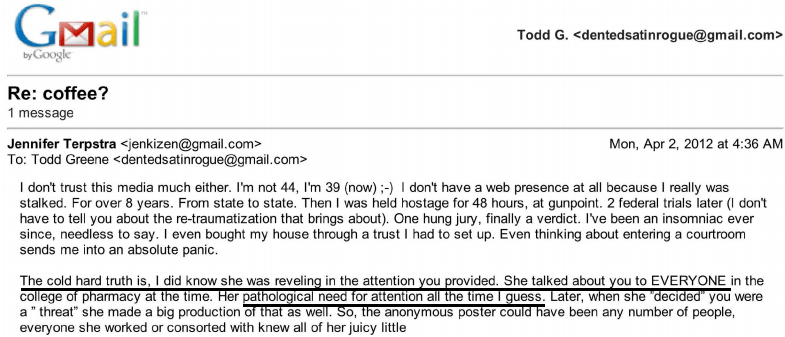

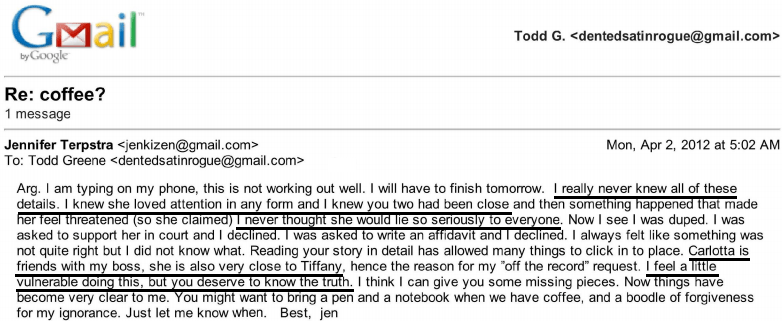

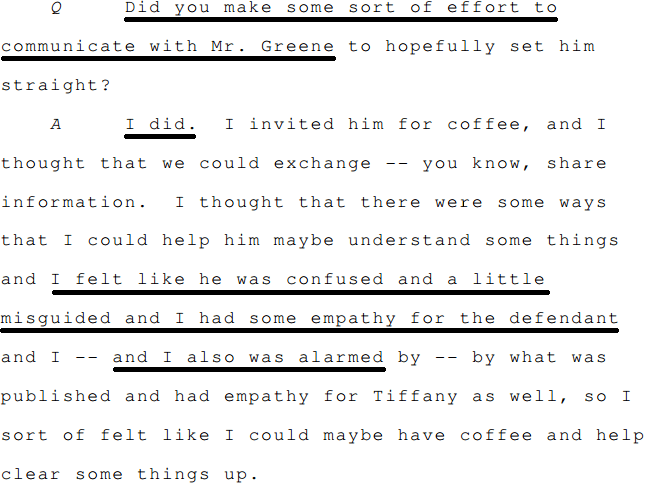

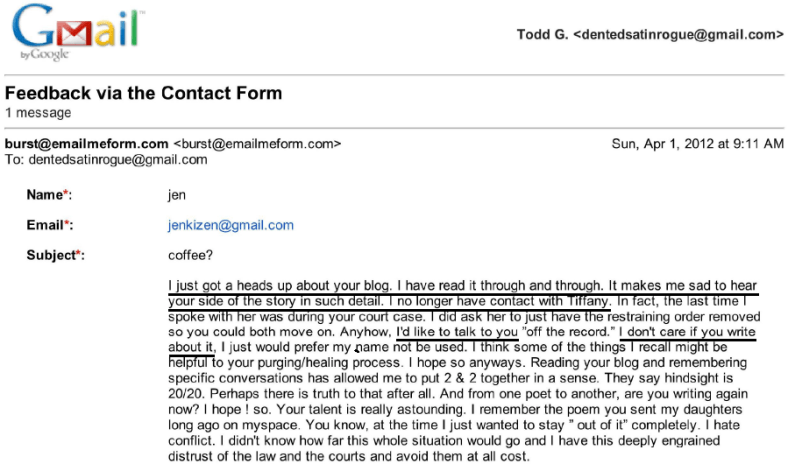

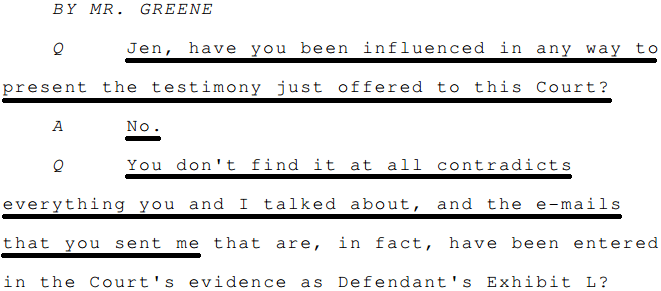

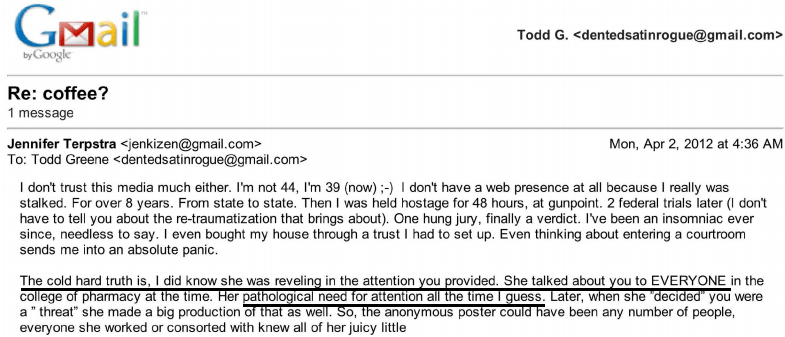

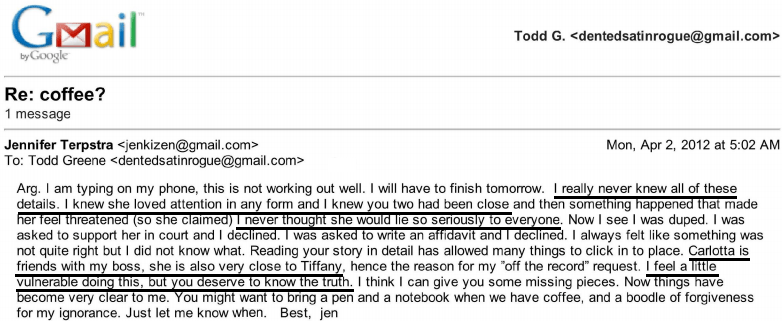

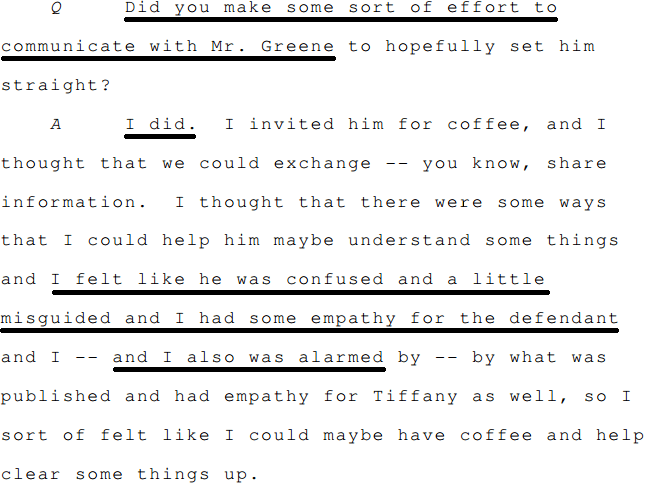

JENNIFER (OAS-)TERPSTRA, Bredfeldt’s other witness in 2013, a former colleague of hers from her University of Arizona days who went by Jenn Oas when the writer was introduced to her in 2005, in an email to the writer sent April 2, 2012 (a year earlier):

This and the rest of Terpstra’s some two dozen emails to the writer in 2012 have been submitted to the court in multiple cases and are public documents accessible to anyone. Whether the emails have ever been scrutinized by a judge is uncertain. No trial has been conducted since the writer was granted a 20-minute audience before a judge in 2006. The 2013 proceeding from which the focal testimony in this post is drawn was a two-hour “preliminary” hearing. Judge Carmine Cornelio, though he drew the case out for half a year and returned several scalding rulings, found a two-hour hearing to be a sufficient basis for indefinitely depriving the writer of his First Amendment privileges. (When the writer had begun to object in open court to an order that was flagrantly unlawful, the judge threatened to summon security. Among the Arizona Court of Appeals’ stated reasons for denying the writer’s 2017 appeal of the order was that the writer had not “challenged” the judge’s ruling at the time.)

In this email, Terpstra tells the writer she was “stalked [f]or over 8 years [f]rom state to state.” Both Bredfeldt and Terpstra have claimed to be victims of multiple stalkers—including this writer. Bredfeldt, who the writer would be informed four years later has held a black belt in tae kwon do since her teens, came to the writer’s door in 2005 seeking his protection from some “men in a van” who she said had been “stalking” her while she was alone in the dark outside of his residence. Narratives of the “event,” which was unwitnessed and may have had no basis in reality, were circulated by Bredfeldt among other horse boarders on the property where the writer lives. The writer bought a wireless doorbell and installed it by the gate to his yard so that Bredfeldt could summon him quickly in case of a “recurrence.” When he showed it to her, she smiled.

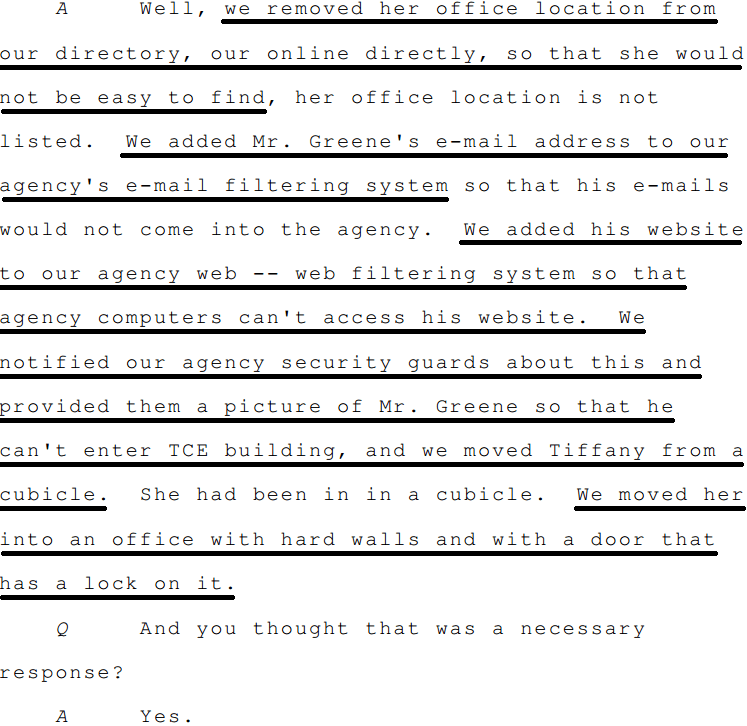

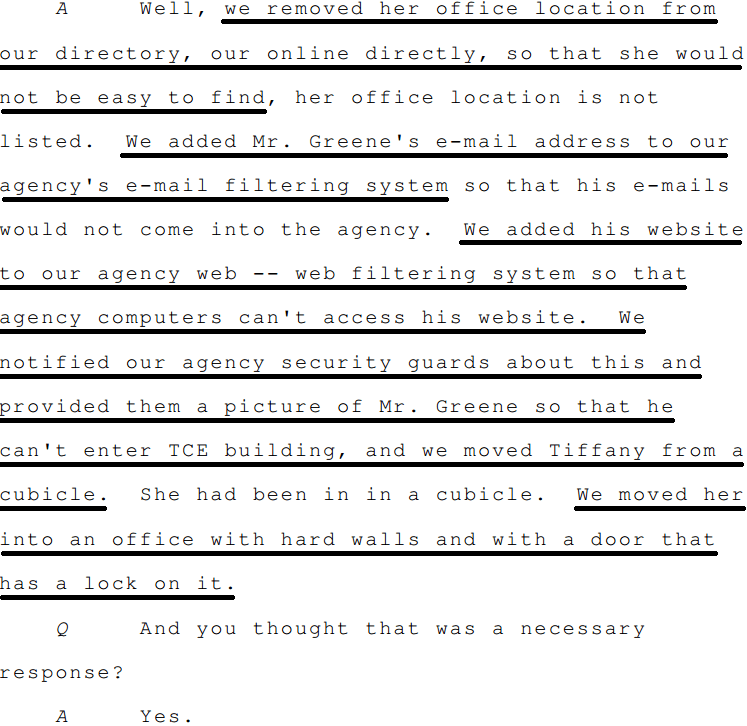

A few months subsequent, when Bredfeldt’s accusations against the writer began, she was reported to have told colleagues that she thought she had seen him around her residence—and at workday’s end would ask to be escorted to her car. In testimony to the court quoted in a postscript to this exposé, Honeycutt, Bredfeldt’s first witness in 2013, says the TCEQ rewarded similar expressions of fear from her by providing her with a private office (“with hard walls and with a door that has a lock on it” in Texas).

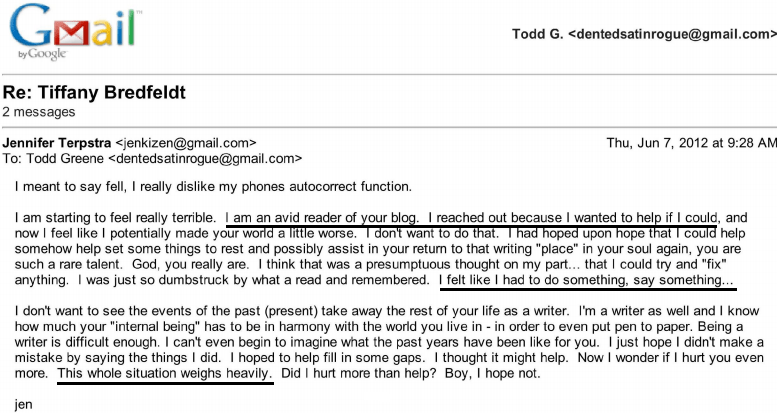

JENNIFER TERPSTRA, in an email to the writer sent April 2, 2012:

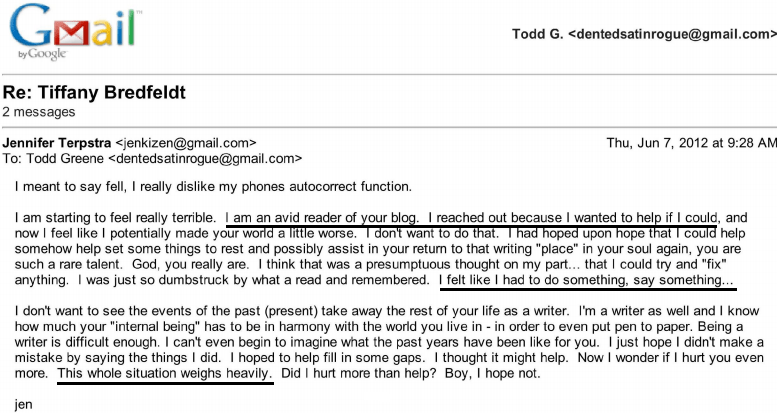

In this email, sent a year before Terpstra would join Bredfeldt in testifying against the writer, Terpstra says that she “never thought [Bredfeldt] would lie so seriously to everyone” and that she knew Bredfeldt and the writer had been “close,” which remark alone contradicts everything Bredfeldt has told the court in the past decade. Terpstra also says she feels professionally “vulnerable” confiding in the writer but that he “deserve[s] to know the truth.” She suggests the writer “bring a pen and a notebook” to a meeting she proposed so that he doesn’t forget anything.

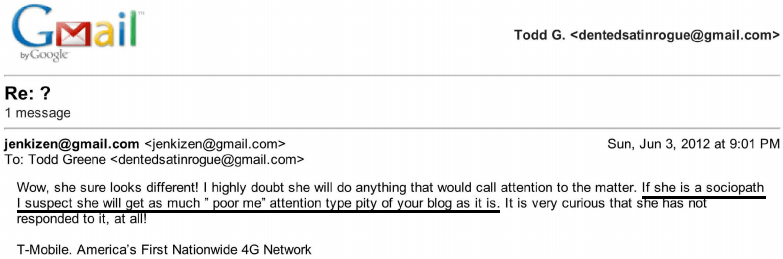

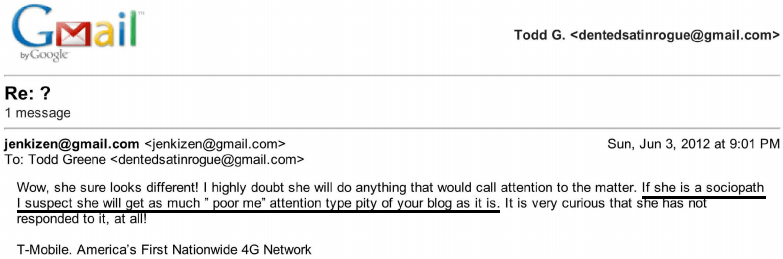

JENNIFER TERPSTRA, in an email to the writer sent June 3, 2012 (a month and a half after the two met for coffee):

Terpstra told the writer over coffee in mid-April 2012 (when his father and his best friend were still alive, and a settlement could have reversed their decline) that Bredfeldt’s spouse, Phil, was known in their circle as “the phantom husband” and that Bredfeldt had urged her friends to go to the writer’s home to “check [him] out”—besides routinely talked about the writer to an audience of “25 or 30 people” at the University of Arizona College of Pharmacy.

Terpstra says in this email that Bredfeldt never talked about her husband and that she (Terpstra) wasn’t sure she had ever seen the man in person or only seen what she had described to the writer over coffee as a laminated newspaper clipping with a picture of him that was tacked to Bredfeldt’s refrigerator. Terpstra says that based on Bredfeldt’s behaviors in 2005, she judged she had been “considering an affair” with the writer, which wildly contradicts any account Bredfeldt has ever related to anybody.

In the first of the emails Terpstra sent him in 2012, she explained her six-year delay in confiding this to the writer by saying, “I don’t lie or bend the truth [but] I do avoid conflict.”

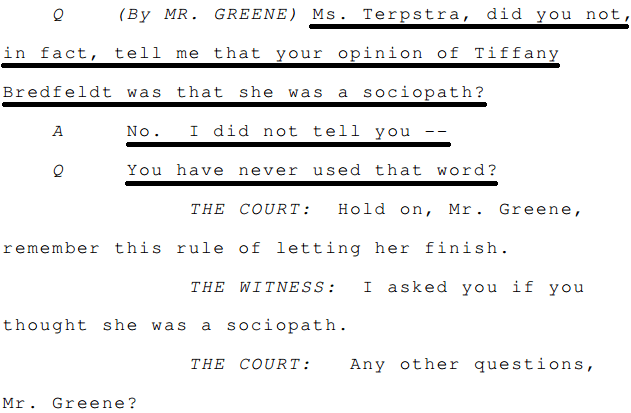

JENNIFER TERPSTRA, on direct examination by Bredfeldt’s attorney, Jeffrey Marks, on May 20, 2013 (less than a year later):

JENNIFER TERPSTRA, in an email to the writer sent April 1, 2012:

In this email, Terpstra tells the writer she had asked Bredfeldt “to just have the restraining order removed” in 2006. (Terpstra would tell the writer the same thing over coffee a couple of weeks later, saying Bredfeldt had answered, “‘No.’ Just…‘no.’”) In contrast to Terpstra’s statements in this email and the others she sent him in 2012, besides in contrast to an email she sent him in 2007, Terpstra would report to Officer Nicole Britt of the Tucson Police Dept. in 2015 that “in 2005 she and her friend [Tiffany Bredfeldt] met [Todd Greene]. He then became fixated on the two of them and began stalking them.” (According to the same interview notes, Terpstra said this blog was “set up in honor” of her and “dedicated” to her.) A couple of months later (early 2016), Terpstra would report to TPD Det. Todd Schladweiler, who is assigned to the Tucson Police Mental Health Support Team, that she “now carries a handgun due to her concern that [Greene] is a threat to her safety.” Det. Schladweiler also recorded that Terpstra “said she communicated with [Greene] a few times [in 2012] and then he became very sexual in nature” and that Terpstra denied contacting the writer after they met for coffee in mid-April 2012, following which meeting she had insisted the writer give her a hug and then emailed and phoned him for a quarter of a year.

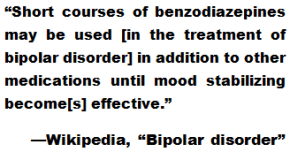

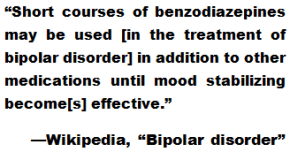

Then students in the University of Arizona College of Pharmacy, Terpstra and Bredfeldt told the writer in 2005, after inviting themselves into his house, that they took “benzos” to relieve stress. The writer asked where they got the drugs. Terpstra (who would marry a former bartender with a cocaine conviction not long afterwards and be charged with DUI in 2011) answered, “From work.” Bredfeldt echoed, “From work.”

Terpstra, who is reportedly diagnosed with bipolar disorder, told Det. Schladweiler she believed the writer was mentally ill. Although Det. Schladweiler was provided with Terpstra’s emails when he arrested the writer on Jan. 5, 2016, the subsequent synopsis of their interview gives no indication the detective spared the emails a glance.

Less than four months after her second police report, in which Terpstra alleged she feared for her safety and was carrying a gun, she would have her home address forwarded to the writer by email in the first of a spate of “copyright infringement” claims that represented her third legal action against him in 2016 and that succeeded in having this blog temporarily suspended by its host. The writer contested the claims, alleging perjury and fraud, and Terpstra declined to litigate them in court.

Terpstra, who has coauthored with Dr. Michael J. Frank, Ph.D., professor of cognitive, linguistic, and psychological sciences at Brown University, is the daughter of feminist painter Joan Bemel Iron Moccasin (Oas) and was employed as a research specialist in the University of Arizona College of Medicine under psychiatrist Francisco Moreno until 2016, when, after making her sundry false allegations, she left the jurisdiction.

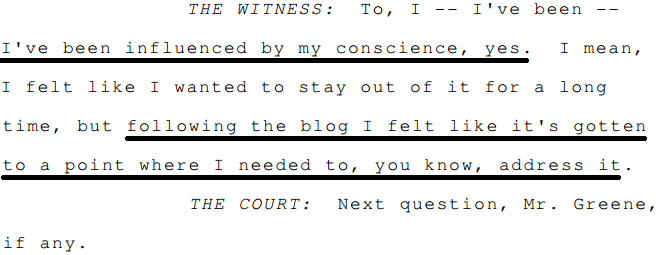

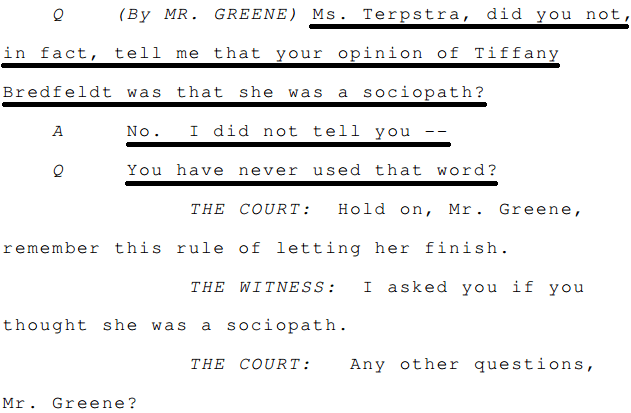

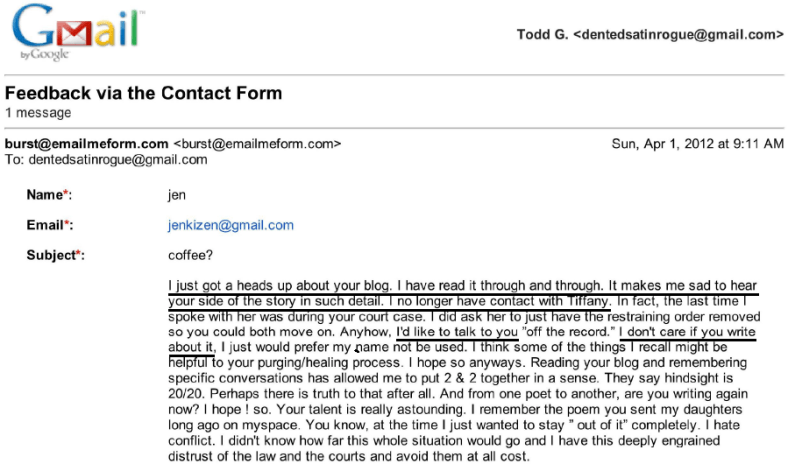

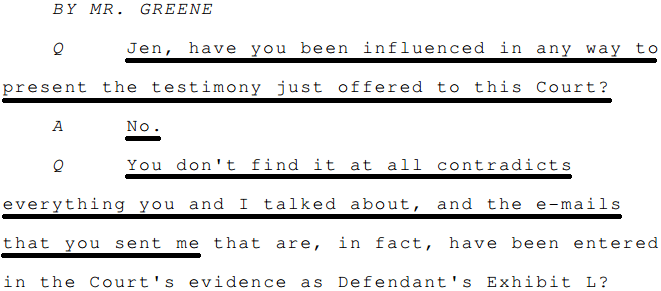

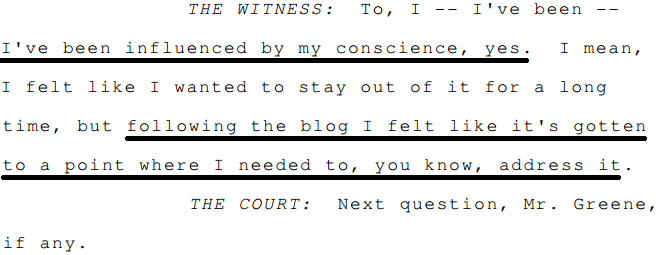

JENNIFER TERPSTRA, on cross-examination by the writer on May 20, 2013:

Over coffee with the writer in 2012, Terpstra complained of financial problems. She also remarked, “Tiffany’s dad has a lot of money.” Tiffany and Phil Bredfeldt’s was a mutually prosperous union of two wealthy, fundamentalist Christian families. Phil Bredfeldt’s father was his best man in 2001; his sister Sara was a bridesmaid; and Tiffany Bredfeldt’s brother, Jon Hargis, was a groomsman. Four years later, Sara Bredfeldt was married to a medical student, Roberto “Bobby” Rojas, who is today an M.D. (Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee).

Tiffany Bredfeldt’s father, Timothy “Tim” Hargis, is or was a bank vice president (First Security of Arkansas), as was his father before him. Phil Bredfeldt’s father, Raymond “Ray” Bredfeldt, is a family physician who practiced privately and besides rented his credentials to Arkansas Blue Cross and Blue Shield for some dozen years. The starting salary for an ABCBS regional medical director is today around $180,000. Dr. Ray Bredfeldt, M.D., had volunteered to join Terpstra in giving witness testimony in 2016 that was meant to induce the court to jail the writer while the writer’s own father, who didn’t graduate from high school, lay dying—in a home in foreclosure. Ray and Ruth Bredfeldt and Tim and GaLyn Hargis have known of what this post details from the start and have temporized for over a decade rather than acknowledge any liability for their families’ ways. “It’s what people like that do,” Terpstra commented to the writer in 2012. (Testifying in 2016, while his father was nearby, Phil Bredfeldt acknowledged on the stand that he was very aware of Terpstra’s 2012 emails. He quoted a post about them. Construing his statements to the court, the only thing that disturbed him about the emails was their contents’ being public.)

Tiffany Bredfeldt’s father, Timothy “Tim” Hargis, is or was a bank vice president (First Security of Arkansas), as was his father before him. Phil Bredfeldt’s father, Raymond “Ray” Bredfeldt, is a family physician who practiced privately and besides rented his credentials to Arkansas Blue Cross and Blue Shield for some dozen years. The starting salary for an ABCBS regional medical director is today around $180,000. Dr. Ray Bredfeldt, M.D., had volunteered to join Terpstra in giving witness testimony in 2016 that was meant to induce the court to jail the writer while the writer’s own father, who didn’t graduate from high school, lay dying—in a home in foreclosure. Ray and Ruth Bredfeldt and Tim and GaLyn Hargis have known of what this post details from the start and have temporized for over a decade rather than acknowledge any liability for their families’ ways. “It’s what people like that do,” Terpstra commented to the writer in 2012. (Testifying in 2016, while his father was nearby, Phil Bredfeldt acknowledged on the stand that he was very aware of Terpstra’s 2012 emails. He quoted a post about them. Construing his statements to the court, the only thing that disturbed him about the emails was their contents’ being public.)

The court was told on Dec. 21, 2016, that Terpstra, who was sued to have her evicted from her house the year before, had moved from Arizona to Texas, where Tiffany and Phil Bredfeldt have resided since 2006 (in a house Terpstra told the writer that Tiffany Bredfeldt’s father had bought for them)—and the writer would be surprised if Terpstra’s legal representation in 2016 and 2017 cost her a penny.

JENNIFER TERPSTRA, on cross-examination by the writer on May 20, 2013:

JENNIFER TERPSTRA, in an email to the writer sent June 7, 2012:

JENNIFER TERPSTRA, on cross-examination by the writer on May 20, 2013:

JENNIFER TERPSTRA, in an email to the writer sent June 3, 2012:

Jennifer Oas-Terpstra, whom the writer has met three times in his life and only once in the past decade (and with whom he has had no contact since 2012), brought three legal actions against him in 2016 that each sought to suppress the emails quoted above—emails that today implicate both Bredfeldt and her (and criminal statutes of limitation, like those for false reporting and forswearing, stop running when perpetrators are outside of the state’s boundaries). Terpstra’s actions included a criminal prosecution, dismissed seven months later, in which Bredfeldt was also named a plaintiff, and a restraining order identical to the one Bredfeldt petitioned in 2006, which had inspired this blog and inspired Terpstra to tell the writer in 2012: “I can’t even begin to imagine what the past years have been like for you.” Terpstra’s restraining order was dismissed 20 months later.

Here are the allegations Terpstra made in her affidavit. These ex parte allegations remain a public record indefinitely. Here, in contrast, is how “vindication” from them appears. The writer was told that this handwritten dismissal, which required eight months of appeals to obtain, exists as a piece of paper only and won’t be reflected in the digitized record. Judge Antonio Riojas, who granted the Aug. 25, 2017 dismissal, accordingly recommended that the writer “carry [it] with [him].” His clerk provided the writer with the yellow copy of the triplicate form, the one meant for the plaintiff, who never appeared in court and will never be criminally accountable for her false allegations to the police in 2015 and 2016.

“I’ve been doing this for 20 years,” Judge Riojas told the writer, “and I’ve never known a police [officer] or a prosecutor to charge someone for…false reports, no matter how blatant….” He added: “I wish they would, because I think people come in, and they say things that are just blatantly false—and lying.” A false or vexatious complainant “can keep filing as much as [s/he] wants,” Judge Riojas said (costing an attorney-represented defendant thousands of dollars a pop and his or her accuser nothing; application is free to all comers). “There is no mechanism to stop someone from filing these orders.” What may be worse, even a dismissed order, the judge explained, “can’t be expunged” (and anything may be alleged on a fill-in-the-blank civil injunction form, for example, rape, conspiracy to commit murder, or cross-dressing; whether heinous or merely humiliating, allegations that may be irrelevant to the approval of a keep-away order and/or that may never be litigated in court, let alone substantiated, will still be preserved indefinitely in the public record above a judge’s signature). Significantly, Judge Riojas, who is the presiding magistrate of the Tucson municipal court (and a member of the Arizona Judicial Council and the Task Force on Fair Justice for All), agreed that restraining orders were “abused”. Of that, he said, “[t]here’s no doubt.”

(In a given year, there are reportedly 5,000 active restraining orders in Tucson City Court, which recently added an annex dedicated to their administration exclusively—and the municipal court is just one of three courts in Tucson that issue such orders.)

Judge Wendy Million

The reason Judge Riojas had to dismiss the order against the writer, nine months after he requested his day in court, was that the writer had been denied his statutory right to a hearing by Judge Wendy Million, necessitating a lengthy appeal and her admonishment by Superior Court Judge Catherine Woods for abuse of discretion. (Among approximately 15 judges to have been exposed to some aspect of this matter, Judge Woods was the first to return a ruling clearly untainted by political motives, for which she has this defendant’s highest respect.) Judge Million, who twice continued the writer’s hearing until the injunction expired and then nominated the case a “dead file,” notably coordinates Tucson’s domestic violence court and is acknowledged as an editor of Arizona’s Domestic Violence and Protective Order Bench Book. Dismissal of the case was further delayed by Judge Cynthia Kuhn, who was first assigned to the writer’s superior court appeal. Judge Kuhn sua sponte (that is, without being asked) granted Terpstra’s attorney additional time to respond to the writer’s appellate memorandum—and then abruptly recused herself, citing an unspecified “conflict of interest” as the reason.

Terpstra, in the first of the 22 emails she sent him in 2012, had told the writer: “I have this deeply engrained distrust of the law and the courts and avoid them at all cost.” Besides witnessing against him in May 2013, accusing him to the police in Nov. 2015, petitioning a civil injunction and instigating a criminal prosecution a month after that, filing a second police report in Jan. 2016, and threatening to sue him in federal court for copyright infringement 14 weeks later, Terpstra was poised to witness against the writer all over again that summer in the lawsuit brought by Bredfeldt and her husband that demanded the writer be jailed for contempt of the 2013 prior restraint. In between, in 2014, Terpstra prosecuted her husband, alleging domestic violence. A relative of his, who afterwards wept, told the writer in 2016 that she believed the man was relentlessly provoked, which the writer finds more than credible. In a voicemail Terpstra left him in 2012 (in which she tacitly identifies Bredfeldt as a “crazy person” from the writer’s “life book”), Terpstra told the writer someone had “threatened to call the police on [her].” Later, by phone, she clarified that this was another man she had been corresponding with that year—who blamed her for a woman’s suicide.

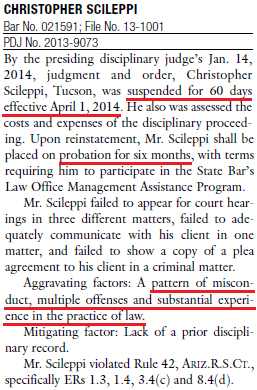

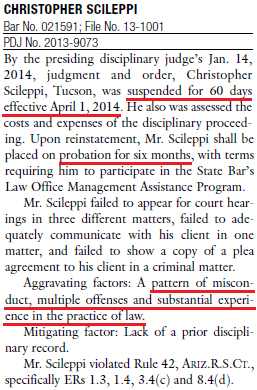

Attorney Christopher Scileppi

Bredfeldt and Terpstra, (carrion) birds of a feather, were represented by the same (criminal) attorney in 2016 and 2017, Christopher “Chris” Scileppi, whose plumage is no different from theirs. Scileppi attained minor notoriety in 2008 for having been given a hug by his “very close friend” the mayor in front of jurors at a rape trial in which Scileppi represented one of the alleged rapists of a 15-year-old girl. Scileppi remarked to the outraged judge: “Courtrooms are open to the public, and I don’t think it is inappropriate when high-profile people come in and show support for somebody who is on trial.” Scileppi’s client was cut free, but the mayor later did a stint in prison for public corruption despite Scileppi’s representation.

Showing the same unscrupulousness during hearings in the 2016 civil case, Bredfeldt v. Greene, Scileppi threatened in open court to prosecute the writer for purported felony crimes (“extortion” and “aggravated harassment,” specifically) to intimidate him into capitulating to Bredfeldt’s censorship demands, then offered to drop the lawsuit if the writer agreed to leave this site invisible to the public and accessible by request only (apparently because his clients’ fear would be eased if they didn’t know what was on the writer’s mind), and finally, as a Parthian shot, directed the judge to jail the writer for the nonpayment of a $350 sanction from 2013 (explained below): “Put him in contempt,” Scileppi said, “and somebody can post a bond and pay that and then he will be released as soon as that bond is posted….”

Scileppi, who was suspended for 60 days and placed on six months’ probation in 2014 for violating various ethical rules (ERs), endeavored to convince the 2016 court that the writer had “terrorize[d], demonize[d], harass[ed], and defame[d]” the Bredfeldts, in particular through the use of “[meta] tags” on this blog, that is, keywords that describe its contents. These terms, which haven’t been used by any major search engine in eight years, were alleged to have hijacked the Bredfeldts’ public images on Google and to have “contact[ed]” anyone whose name appeared among them. Because a Google Alert Phil Bredfeldt had “set up” had allegedly been triggered by tags on the blog (in publications to the world at large), that was said to represent illicit “communication [and] contact” by the writer with Mr. Bredfeldt and his wife. Scileppi enlisted an information technology expert, “part-time professor” and (criminal) attorney Brian Chase, to loosely substantiate this theory on the stand. Lamely objecting to an eminent constitutional scholar’s weighing in as an amicus curiae (Latin for “friend of the court”), Scileppi also defended the 2013 prior restraint last year before the Arizona Court of Appeals. He told the court that the writer was the liar.

Scileppi, who was suspended for 60 days and placed on six months’ probation in 2014 for violating various ethical rules (ERs), endeavored to convince the 2016 court that the writer had “terrorize[d], demonize[d], harass[ed], and defame[d]” the Bredfeldts, in particular through the use of “[meta] tags” on this blog, that is, keywords that describe its contents. These terms, which haven’t been used by any major search engine in eight years, were alleged to have hijacked the Bredfeldts’ public images on Google and to have “contact[ed]” anyone whose name appeared among them. Because a Google Alert Phil Bredfeldt had “set up” had allegedly been triggered by tags on the blog (in publications to the world at large), that was said to represent illicit “communication [and] contact” by the writer with Mr. Bredfeldt and his wife. Scileppi enlisted an information technology expert, “part-time professor” and (criminal) attorney Brian Chase, to loosely substantiate this theory on the stand. Lamely objecting to an eminent constitutional scholar’s weighing in as an amicus curiae (Latin for “friend of the court”), Scileppi also defended the 2013 prior restraint last year before the Arizona Court of Appeals. He told the court that the writer was the liar.

Jeffrey “25% OFF ALL MONTH LONG” Marks, the low-rent opportunist who represented Tiffany Bredfeldt in 2010 and 2013, and is quoted below, represented her in 2016, also, but was hastily replaced after the writer was granted a court-appointed lawyer of his own. Marks, like his replacement, Scileppi, attempted to induce the court to stifle even third-party criticism of Bredfeldt, for example, that of Georgia entrepreneur Matthew Chan, who (aided by Prof. Eugene Volokh) successfully appealed a prior restraint in 2015 in his state’s supreme court and who introduced the writer to the finer points of First Amendment law.

To explain away Terpstra’s emails to the writer in 2012 and the contradictory testimony she gave a year later, Scileppi told Judge Catherine Woods in 2017 that “[i]n the midst of Greene’s harassment of Dr. Bredfeldt, [Terpstra] reached out to Greene and met with him. Through meeting with Greene, Terpstra became privy to his harassment of Dr. Bredfeldt.” In contrast to Scileppi’s claims, which Judge Woods shrewdly disregarded, Terpstra had offered to help the writer settle the conflict with Bredfeldt in 2012 (three months after Terpstra “reached out to [the writer] and met with him”). In an email Terpstra sent the writer on July 18 of that year (the first of four she sent that day), she wrote: “Maybe I can be a go between if the pastor [Jeremy Cheezum, a brother-in-law of Phil Bredfeldt’s] will not. I told Tiffany we met for coffee.” The email ended, “Hoping for the best.” That was the last day the writer heard from Terpstra, who is notably the mother of two college-aged daughters. Desperate to raise money to secure a surgery for his dog to enable her to run and jump again—something else Terpstra had said she was eager to help him accomplish—the writer scarcely gave Terpstra another thought until she appeared as a surprise witness 10 months later and deceived the court for Bredfeldt.

The other friend of Bredfeldt’s the writer met at his home in 2005, Dr. Carlotta Groves, a reported recipient of $740,000 in scientific research grants who uses the alias “Jahchannah” and identifies herself as a “Black Hebrew Israelite” and “servant of Yah,” lives in Arizona but apparently couldn’t be persuaded to give witness testimony for Bredfeldt in either 2013 or 2016. Like Terpstra did in the first of her emails to the writer in 2012, Groves told him in a blog comment around the same time that her own brother had been falsely accused. Terpstra said her brother had been falsely accused of rape and that it had “truly ruined his life.” For 12 years, Groves has done what Terpstra did for six: spectate. Groves, a DVM and a Ph.D. (who “love[s] to read and support aspiring authors!”), works at a low-cost veterinary clinic in Tucson.

TIFFANY BREDFELDT, on cross-examination by the writer on May 20, 2013:

TIFFANY BREDFELDT, on cross-examination by the writer on May 20, 2013:

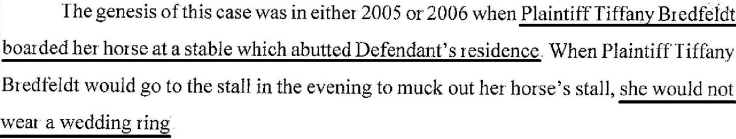

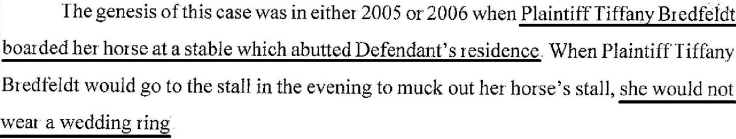

JEFFREY MARKS, Bredfeldt’s attorney, speaking for her in a memorandum to the court filed July 10, 2013:

The difference between Bredfeldt’s attorney’s offhand estimation, “2005 or 2006,” was a year of this writer’s life (and his friends’ and his family’s). The year after the “genesis of this case” was one the writer spent every waking moment conscious he could be arrested without a warrant based on a further contrived allegation by Bredfeldt (in which case the writer’s dog, who was part Rottweiler and vigorously barked at any approaching stranger, could easily have been shot and killed).

Contrary to Marks’s claim, Bredfeldt employed others to tend to her horse’s daily hygiene in 2005. Within six or seven weeks of her installing her horse 30′ from the writer’s residence, it became lame and could not even be ridden, after which Bredfeldt increased the frequency of her nighttime visits.

Marks, who boasts of having served as a superior court judge himself, also tells the court in this memorandum, which was captioned, “Plaintiffs’ Response to Defendant’s ‘Chronology of Tiffany Bredfeldt’s 2006 Frauds,’” that “[e]ven assuming arguendo that Plaintiff Tiffany Bredfeldt is a chronic liar, her veracity is totally irrelevant to the necessity to restrain Defendant’s [speech] conduct.” Marks moved the 2013 court to strike the writer’s “scandalous” chronology from the record so that it couldn’t be accessed by the public. The judge, Carmine Cornelio, complied, rebuked the writer, and sanctioned him $350 for filing the brief, despite having invited him to: “Mr. Greene,” the judge had said in open court, “you can file anything you want.” Then the judge permanently prohibited the writer from telling anyone else what that chronology related—including by word of mouth. Bredfeldt’s handmaidens, Honeycutt and Terpstra, said exactly what they knew they should to inspire the illegal injunction. The judge permanently prohibited the writer from talking about them, also, including by reporting the testimony they gave in a public proceeding in the United States of America.

Marks, who boasts of having served as a superior court judge himself, also tells the court in this memorandum, which was captioned, “Plaintiffs’ Response to Defendant’s ‘Chronology of Tiffany Bredfeldt’s 2006 Frauds,’” that “[e]ven assuming arguendo that Plaintiff Tiffany Bredfeldt is a chronic liar, her veracity is totally irrelevant to the necessity to restrain Defendant’s [speech] conduct.” Marks moved the 2013 court to strike the writer’s “scandalous” chronology from the record so that it couldn’t be accessed by the public. The judge, Carmine Cornelio, complied, rebuked the writer, and sanctioned him $350 for filing the brief, despite having invited him to: “Mr. Greene,” the judge had said in open court, “you can file anything you want.” Then the judge permanently prohibited the writer from telling anyone else what that chronology related—including by word of mouth. Bredfeldt’s handmaidens, Honeycutt and Terpstra, said exactly what they knew they should to inspire the illegal injunction. The judge permanently prohibited the writer from talking about them, also, including by reporting the testimony they gave in a public proceeding in the United States of America.

(Last year, two days before the writer’s attorney would file an appeal reminding an American court that citizens of this country enjoy freedom of speech, The New York Times published an editorial on censorship in China adapted from an essay by iconic artist and agitator Ai Weiwei. In it, Ai argues that censorship, an essential tool of oppression, does the opposite of pacify: It stimulates “behavior [that] can become wild, abnormal and violent.” Having to live with lies, as Ai told NPR in an interview in 2013, “is suffocating. It’s like bad air all the time.”)

MICHAEL HONEYCUTT, on cross-examination by the writer on May 20, 2013:

MICHAEL HONEYCUTT, on direct examination by Bredfeldt’s attorney, Jeffrey Marks, on May 20, 2013:

The testimony of “Where’s my mike?” Honeycutt exemplifies how the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality responds to “pretty significant allegations” of ethical misconduct by its scientists: It ignores the allegations…and abets the misconduct.

Under Arizona law, a “false sworn statement in regard to a material issue” is perjury, a felony crime. Honeycutt influentially testified in 2013 that the writer had called Bredfeldt a “fraudulent scientist.” Here, in contrast, is what the writer told Honeycutt in 2011, in a letter that is today a public document.

In the Texas Observer the summer before last, Naveena Sadasivam reported that “Honeycutt sent at least 100 emails to state air pollution regulators, university professors and industry representatives and lawyers asking them to send the EPA a letter supporting his nomination to the Clean Air Science Advisory Committee….” Probably none of them sought to have him silenced on pain of imprisonment for requesting support. In a further instance of incandescent hypocrisy, Honeycutt is quoted in the story as pronouncing: “Ideology is different from science and data.” The reader is invited to consider which master Honeycutt was serving when he testified against this writer four and a half years ago.

In the Texas Observer the summer before last, Naveena Sadasivam reported that “Honeycutt sent at least 100 emails to state air pollution regulators, university professors and industry representatives and lawyers asking them to send the EPA a letter supporting his nomination to the Clean Air Science Advisory Committee….” Probably none of them sought to have him silenced on pain of imprisonment for requesting support. In a further instance of incandescent hypocrisy, Honeycutt is quoted in the story as pronouncing: “Ideology is different from science and data.” The reader is invited to consider which master Honeycutt was serving when he testified against this writer four and a half years ago.

After a hearing held on July 15, 2016, during which her husband had testified he was “frighten[ed],” Tiffany Bredfeldt swore in court, “God damn it,” because instead of ordering that the writer be jailed, the judge had stayed the proceedings pending further briefings from the attorneys on the First Amendment. Then, less than a year after the writer had buried his best friend and a few months before the writer’s father would succumb to cancer by starving to death, Bredfeldt laughed. She said Honeycutt had joked that her prosecution of the writer was “good experience” for when she gave expert witness testimony. “That’s something we have to do,” Bredfeldt explained to her entourage.

Copyright © 2018 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

DR. MICHAEL HONEYCUTT, PH.D.:

DR. TIFFANY BREDFELDT, PH.D.:

Tiffany Bredfeldt’s father, Timothy “Tim” Hargis, is or was a

Tiffany Bredfeldt’s father, Timothy “Tim” Hargis, is or was a

Not only is false accusation culture real; it extends beyond the quad.

Not only is false accusation culture real; it extends beyond the quad. Feminists provoke animosity—which rightly or wrongly may be directed toward all women—and then they denounce that animosity as misogyny…which provokes more animosity…which is denounced as misogyny (and on and on). “Rape deniers” may simply be people who’ve been conditioned to distrust accusations of violence from women and to hate feminists.

Feminists provoke animosity—which rightly or wrongly may be directed toward all women—and then they denounce that animosity as misogyny…which provokes more animosity…which is denounced as misogyny (and on and on). “Rape deniers” may simply be people who’ve been conditioned to distrust accusations of violence from women and to hate feminists. Pols and corporations engage in flimflam to win votes and increase profit shares. Science, too, seeks acclaim and profit, and judicial motives aren’t so different. Judges know what’s expected of them, and they know how to interpret information to satisfy expectations.

Pols and corporations engage in flimflam to win votes and increase profit shares. Science, too, seeks acclaim and profit, and judicial motives aren’t so different. Judges know what’s expected of them, and they know how to interpret information to satisfy expectations. Since judges can rule however they want, and since they know that very well, they don’t even have to lie, per se, just massage the facts a little. It’s all about which facts are emphasized and which facts are suppressed, how select facts are interpreted, and whether “fear” can be reasonably inferred from those interpretations. A restraining order ruling can only be construed as “wrong” if it can be demonstrated that it violated statutory law (or the source that that law must answer to:

Since judges can rule however they want, and since they know that very well, they don’t even have to lie, per se, just massage the facts a little. It’s all about which facts are emphasized and which facts are suppressed, how select facts are interpreted, and whether “fear” can be reasonably inferred from those interpretations. A restraining order ruling can only be construed as “wrong” if it can be demonstrated that it violated statutory law (or the source that that law must answer to:  Feminism’s foot soldiers in the blogosphere and on social media, finally, spread the “good word,” and John and Jane Doe believe what they’re told—unless or until they’re torturously disabused of their illusions. Stories like those you’ll find

Feminism’s foot soldiers in the blogosphere and on social media, finally, spread the “good word,” and John and Jane Doe believe what they’re told—unless or until they’re torturously disabused of their illusions. Stories like those you’ll find

It gets by with a little help from its friends.

It gets by with a little help from its friends. Prof. Meier says she expects to use the $500,000 federal grant to conclusively expose gender bias in family court against women—and to do it using a study sample of “over 1,000 court cases from the past 15 years” (a study sample, in other words, of fewer than 2,000 cases).

Prof. Meier says she expects to use the $500,000 federal grant to conclusively expose gender bias in family court against women—and to do it using a study sample of “over 1,000 court cases from the past 15 years” (a study sample, in other words, of fewer than 2,000 cases).

Some recent posts on this blog have touched on what might be called the five magic words, because their utterance may be all that’s required of a petitioner to obtain a restraining order. The five magic words are these: “I’m afraid for my life.”

Some recent posts on this blog have touched on what might be called the five magic words, because their utterance may be all that’s required of a petitioner to obtain a restraining order. The five magic words are these: “I’m afraid for my life.” Gamesmanship in this arena is both bottom-up and top-down. Liars hustle judges…and judges hustle liars along.

Gamesmanship in this arena is both bottom-up and top-down. Liars hustle judges…and judges hustle liars along.

People falsely alleged to be abusers on restraining order petitions, particularly men, are treated like brutes, sex offenders, and scum by officers of the court and its staff, besides by authorities and any number of others. Some report their own relatives remain suspicious—often based merely on finger-pointing that’s validated by some judge in a few-minute procedure (and that’s when relatives aren’t the ones making the false allegations).

People falsely alleged to be abusers on restraining order petitions, particularly men, are treated like brutes, sex offenders, and scum by officers of the court and its staff, besides by authorities and any number of others. Some report their own relatives remain suspicious—often based merely on finger-pointing that’s validated by some judge in a few-minute procedure (and that’s when relatives aren’t the ones making the false allegations). So…slanders and libels made by abuse of court process aren’t actionable, slanders and libels that completely sunder the lives of the wrongly accused, who can’t even get them expunged from their records to simply reset their fractured lives to zero.

So…slanders and libels made by abuse of court process aren’t actionable, slanders and libels that completely sunder the lives of the wrongly accused, who can’t even get them expunged from their records to simply reset their fractured lives to zero. Under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), some

Under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), some  All of this is to say that if you issue 60 restraining orders against nonviolent people to every one issued against a violent aggressor, violations of restraining orders resulting in injuries or death will be comparatively few respective to the total number of people “restrained.” It skews the odds in favor of positive perception.

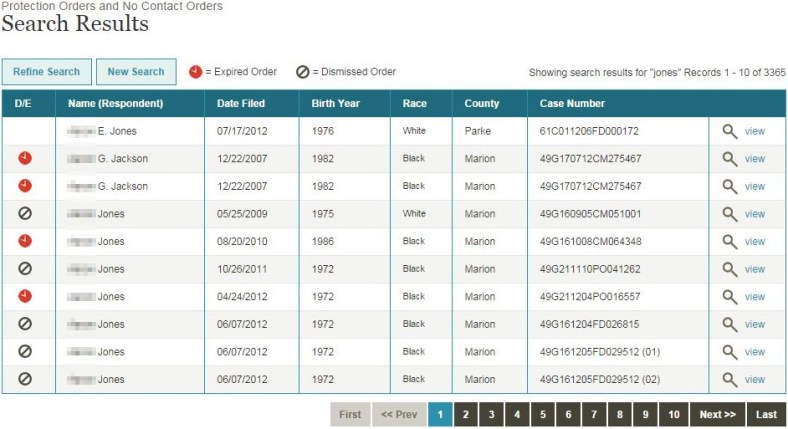

All of this is to say that if you issue 60 restraining orders against nonviolent people to every one issued against a violent aggressor, violations of restraining orders resulting in injuries or death will be comparatively few respective to the total number of people “restrained.” It skews the odds in favor of positive perception. One of the thrusts of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) has been to establish public restraining order registries like those that identify sex offenders.

One of the thrusts of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) has been to establish public restraining order registries like those that identify sex offenders.

Ironic is that Dr. Behre’s denial of men’s groups’ position that men aren’t treated fairly is itself unfair.

Ironic is that Dr. Behre’s denial of men’s groups’ position that men aren’t treated fairly is itself unfair.