“She habitually engages in psychological projection. She has caused me to be compelled under threat of arrest and prosecution for failure to appear to attend court on her frivolous lawsuits 25 times. Yes! Twenty-five times. The frivolous prosecutions started in 2011, and they are still raging. I have been cited back to court on her application for a new restraining order on the 12th and a criminal warrant for cyberstalking on the 17th of this month. She has tried so many times to have me jailed I have lost count.”

—Larry Smith, author of BuncyBlawg.com (2014)

The quotation above is an excerpt from an email sent to the creator of “Neighbors from Hell” on ABC’s 20/20. The Feb. 8 email was a sorely persecuted man’s response to being fingered on Facebook as a candidate for the series by his neighbor, Marty Tackitt-Grist, who has forced him to appear before judges nearly 30 times in the span of a few years to answer “two restraining orders, three show-cause orders, two cyberstalking arrests, and a failure-to-appear arrest and jailing despite faxes from two doctors that I was too crippled, disabled, and suffering from herniated discs to be able to attend court.”

Here’s the reply the email elicited from ABC’s Bob Borzotta: “Hi Larry, I don’t seem to have heard further from her. Sounds like quite a situation….” Cursory validations like this one are the closest thing to solace that victims of chronic legal abuses can expect.

Here’s the reply the email elicited from ABC’s Bob Borzotta: “Hi Larry, I don’t seem to have heard further from her. Sounds like quite a situation….” Cursory validations like this one are the closest thing to solace that victims of chronic legal abuses can expect.

Concern shown by the police and courts to complaints from attention-seekers can make them feel like celebrities. Random wild accusations are all it takes for the perennial extra in life to realize his or her name in lights.

Not unpredictably, the thrill is addictive.

I think I first heard from Larry, the author of BuncyBlawg.com, in 2013—or maybe it was 2012. In the artificial limbo created by “high-conflict” people like the one he describes in the epigraph, temporal guideposts are few and far between. A target like Larry can find him- or herself living the same day over and over for years, because s/he’s unable to plan, look forward to anything, or even enjoy a moment’s tranquility.

The target of a high-conflict person is perpetually on the defensive, trying to recover his or her former life from the unrelenting grasp of a crank with an extreme (and often pathological) investment in eroding that life for self-aggrandizement and -gratification.

The target of a high-conflict person is perpetually on the defensive, trying to recover his or her former life from the unrelenting grasp of a crank with an extreme (and often pathological) investment in eroding that life for self-aggrandizement and -gratification.

Among Larry’s neighbor’s published allegations are that he’s a disbarred attorney who “embezzled from his clients” and a textbook psychopath, that he has “barked like a dog for hours” to provoke another neighbor’s (imaginary) dog to howl at her, that he has called her names, that he has enlisted “mentally challenged adults” to harass her while shopping, that he has cyberstalked her, that he has “hacked into phones” and computers, that he has tried to cause her (and “many others”) to lose their jobs by “reporting false information,” that he has made false complaints about her “to every city, state, and county service,” that he sends her mail “constantly,” and that he has “mooned” her neighbors and friends.

The ease with which a restraining order is obtained encourages outrageous defamations like these (Larry’s neighbor has sworn out two). Once a high-conflict person sees how readily any fantastical allegation can be put over on the police and courts, s/he’s inspired to unleash his or her imagination. That piece of paper not only licenses lies; it motivates them.

The ease with which a restraining order is obtained encourages outrageous defamations like these (Larry’s neighbor has sworn out two). Once a high-conflict person sees how readily any fantastical allegation can be put over on the police and courts, s/he’s inspired to unleash his or her imagination. That piece of paper not only licenses lies; it motivates them.

Larry’s a quiet guy with a degenerative spinal disorder who’s been progressively going deaf for 25 years. He lives for his three toy poodles and watches birds. “I grew up,” he says, “in a little Arcadian valley here in western North Carolina with the nicest people, mostly farmers; and I guess my youth just left me naïve about some people. I always saw the good in them.” Larry began practicing law in 1973 in Asheville but voluntarily withdrew from the profession in 1986, because he was disgusted by the corruption—and the irony of having his retirement years fouled by that corruption isn’t lost on him.

You might guess his accuser’s motive to be that of a woman scorned, but Larry’s association with her has never exceeded that of the usual neighborly sort. He reports, however, that she has alleged in court that he covets her and nurses unrequited longings and desires.

Compare the details of the infamous David Letterman case, and see if you don’t note the same correspondence Larry has.

That’s the horror that only the objects of high-conflict people’s fixations understand. Stalkers and “secret admirers” procure restraining orders to get attention and embed themselves in other’s lives—like shrapnel.

That’s the horror that only the objects of high-conflict people’s fixations understand. Stalkers and “secret admirers” procure restraining orders to get attention and embed themselves in other’s lives—like shrapnel.

This writer has been in and out of court for eight years subsequent to encountering a stranger standing outside of his residence one day…and naïvely welcoming her. One respondent to this blog reported having had a restraining order issued against her by a man she sometimes encountered by her home who always made a point of noticing her but with whom she’d never exchanged a single word.

It isn’t only intimates and exes who lie to subject targets to public humiliation and punishment. Sometimes it’s lurkers and passers-by, covert observers who peer between fence slats and entertain fantasies—or, as in Larry’s case, a neighbor who feels s/he’s been slighted or wronged according to metrics that only make sense to him or her.

Larry thinks the unilateral feud that has exploded the last several years of his life originates with his complaining about cats his neighbor housed, after they savaged the fledgling birds that have always been his springtime joy to watch.

For 25 years I have lived on this street with lovely people. We always got along, although one or two you had to watch. During most of that 25 years, there have been three different owners of the house across the street. The other two we dearly loved. The last one, the incarnation of purest evil, moved here in 2005. She was a divorcée who volunteered that her divorce was especially nasty, the first red flag which I foolishly disregarded: She constantly badmouthed her ex. For the first few years, we were friends, but as time went by she became an almost insufferable mooch and just way too friendly, expecting more attention from her neighbors, and from us, than we wanted to give. Sometime in early 2011, I left her a voicemail and told her I didn’t want to be close friends with her anymore. She was a hoverer, she manipulated, she was a narcissist. And the message meant that I did not want to be called on to mow her lawn anymore, or help her trim her trees, or lend her tools, or watch her pet while she was gone, or help her move heavy loads like furniture, or listen to her constant whining. I just wanted to cool it with her.

In the spring of 2011, she had been converting her home to a sort of boarding house and brought in tenants, and [between] them they had two cats that constantly prowled, especially the tenant’s. What became very irksome to me was the tenant’s cat creeping into our yard and killing our baby birds, which we always looked forward to in the spring. And the minute I brought it up with her, she pitched a fit, and so did the tenant. So for the first two months of baby bird season, [their] cats killed all our fledglings and the mother songbirds—wrens, cardinals, robins, mockingbirds, towhees, mourning doves, even the hummingbirds, just wiped them out. I finally got in touch with our Animal Services officers, but by that time bird season was over with, and you know something, [she] began going about telling neighbors that I was a disbarred lawyer (a particularly nasty slander). One thing led to another, and finally the tenant with the marauding cat moved away, but the irreparable damage was done, and all through the summer I had been warned by other neighbors that the neighbor from hell was plotting revenge.

In the spring of 2011, she had been converting her home to a sort of boarding house and brought in tenants, and [between] them they had two cats that constantly prowled, especially the tenant’s. What became very irksome to me was the tenant’s cat creeping into our yard and killing our baby birds, which we always looked forward to in the spring. And the minute I brought it up with her, she pitched a fit, and so did the tenant. So for the first two months of baby bird season, [their] cats killed all our fledglings and the mother songbirds—wrens, cardinals, robins, mockingbirds, towhees, mourning doves, even the hummingbirds, just wiped them out. I finally got in touch with our Animal Services officers, but by that time bird season was over with, and you know something, [she] began going about telling neighbors that I was a disbarred lawyer (a particularly nasty slander). One thing led to another, and finally the tenant with the marauding cat moved away, but the irreparable damage was done, and all through the summer I had been warned by other neighbors that the neighbor from hell was plotting revenge.

I went to her one day and asked her if there was anything I could do to make it so we could at least drop all the nasty hostilities. She exploded. Next thing I knew, she had three police cruisers here with a false tale that I was “harassing” her and calling her names. This was no surprise, because early on I learned not to believe a thing she said because she just made up the most unbelievable tales about her personal crises. One of the five cops who came spoke with me in the yard, and I thought this would all blow over, but in a few days a process server was banging on the door with papers to serve me. I met him in a commercial parking lot nearby and accepted the lawsuit, an application for a restraining order, a TRO, and, well, a great big wad of lies. It was a shocker. And little did I know that the very day I received this horse-choking wad of papers, at around 10:15 a.m., [she] was back in the courthouse filing another affidavit to have me ordered to show cause why I should not be jailed for contempt. In other words, before I even had notice of the TRO, she was trying to have me jailed for violating it. That’s just how damn mean that woman is.

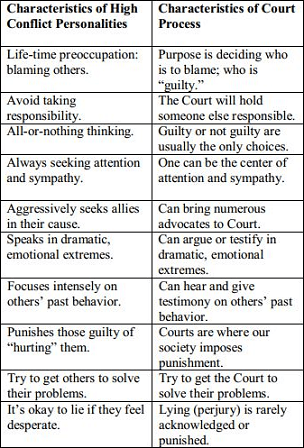

High-conflict people are driven by a lust to punish—any slight is a provocation to go to war—and their craving for attention can be boundless. Judicial process rewards both.

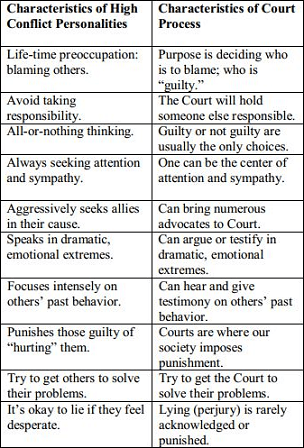

This table, prepared by attorneys Beth E. Maultsby and Kathryn Flowers Samler for the 2013 State Bar of Texas Annual Advanced Family Law Course, shows how high-conflict people and court process are an exquisitely infernal fit. Its authors’ characterization of high-conflict people’s willingness to lie (“if they feel desperate”) is generous. Many lie both on impulse or reflex and with deliberate cunning, though their chain of reasoning may be utterly bizarre.

Restraining orders are easily obtained, particularly by histrionic women. Once petitioners—especially high-conflict petitioners—realize how readily the state’s prepared to credit any evil nonsense they sputter or spew, and once they realize, too, the social hay they can make out of reporting to others that they “had to get a restraining order” (a five-minute affair), they can become accusation junkies.

Larry has responded in the most reasonable way he can to his situation. He’s voiced his outrage and continues to in a blog, and the vehemence of his criticisms might lead some who don’t know Larry to dismiss him as a crank. If you consulted his blog, you’d see it’s fairly rawboned and hardly suggests the craftsmanship of a technical wizard who can hack email accounts and remotely eavesdrop on telephone conversations. What the commentaries there suggest, rather, is the moral umbrage of an intelligent man who’s been acutely, even traumatically sensitized to injustice.

Here’s the diabolical beauty of our restraining order process. Judges accept allegations of abuse at face value and don’t scruple about incising them on the public records of those accused. They furthermore expect those who are defamed to pacifically tolerate public allegations that may have no relationship with reality whatever or may be the opposite of the truth, may be scandalous, and may destroy them socially, professionally, and psychologically. Judges, besides, make the accused vulnerable to any further allegations their accusers may hanker to concoct, which can land them in jail and give them criminal records. And finally judges react with disgust and contempt when the accused ventilate anger, which they may even be punished for doing.

Judicial reasoning apparently runs something like this: If you’re angry about false allegations, then they weren’t false; if you’re not angry about false allegations, then they weren’t false.

Larry’s been jailed, Larry’s been reported to the police a dozen times or more, an officer has rested the laser sight of her sidearm on him through the window of his residence, and the number of times he’s been summoned to court is closing on 30.

The allegations against him have been false. How angry should he be?

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

There are a lot of things judges don’t know, but the law isn’t one of them. Restraining orders are a lawless arena, anyway, so there’s not much to know.

There are a lot of things judges don’t know, but the law isn’t one of them. Restraining orders are a lawless arena, anyway, so there’s not much to know.

A: Right (

A: Right (

During the term of their relationship, no reports of any kind of domestic conflict were made to authorities.

During the term of their relationship, no reports of any kind of domestic conflict were made to authorities. back was turned. Since the woman’s knuckles were plainly lacerated from punching glass, no arrest ensued. According to the man’s stepmother, the woman lied similarly to procure a protection order a couple of days later.

back was turned. Since the woman’s knuckles were plainly lacerated from punching glass, no arrest ensued. According to the man’s stepmother, the woman lied similarly to procure a protection order a couple of days later.

The reason why, basically, is that the system likes closure. Once it rules on something, it doesn’t want to think about it again.

The reason why, basically, is that the system likes closure. Once it rules on something, it doesn’t want to think about it again.

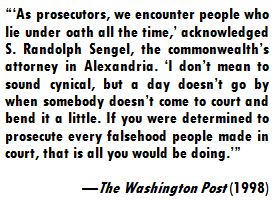

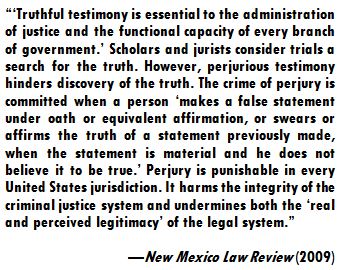

With regard to the honest representation of facts in court, however, both accusers and judges fudge (and that’s putting it mildly). Each may frame facts to produce a favored impression.

With regard to the honest representation of facts in court, however, both accusers and judges fudge (and that’s putting it mildly). Each may frame facts to produce a favored impression.

A recent NPR story reports that dozens of students who’ve been accused of rape are suing their universities. They allege they were denied due process and fair treatment by college investigative committees, that is, that they were “railroaded” (and publicly humiliated and reviled). The basis for a suit alleging civil rights violations, then, might also exist (that is, independent of claims of material privation). Certainly most or all restraining order defendants and many domestic violence defendants are “railroaded” and subjected to public shaming and social rejection unjustly.

A recent NPR story reports that dozens of students who’ve been accused of rape are suing their universities. They allege they were denied due process and fair treatment by college investigative committees, that is, that they were “railroaded” (and publicly humiliated and reviled). The basis for a suit alleging civil rights violations, then, might also exist (that is, independent of claims of material privation). Certainly most or all restraining order defendants and many domestic violence defendants are “railroaded” and subjected to public shaming and social rejection unjustly. Undertaking a venture like coordinating a class action is beyond the resources of this writer, but anyone with the gumption to try and transform words into action is welcome to post a notice here.

Undertaking a venture like coordinating a class action is beyond the resources of this writer, but anyone with the gumption to try and transform words into action is welcome to post a notice here.

The scales of justice are tipped from the start.

The scales of justice are tipped from the start. The savvy observer will note that suspicion is the motive determiner of liability at all levels. Suspicion informs judicial disposition, subsequent police response to claims of violation, and of course interpretation by third parties, including employers (judges trust accusers, and everyone else trusts judges). Emphatically worthy of remark is that

The savvy observer will note that suspicion is the motive determiner of liability at all levels. Suspicion informs judicial disposition, subsequent police response to claims of violation, and of course interpretation by third parties, including employers (judges trust accusers, and everyone else trusts judges). Emphatically worthy of remark is that  From these concepts, questions immediately present themselves. Are protection orders being utilized in oppressive or unexpected ways? Are the factual scenarios involved similar to what the [legislature] envisioned them to be? Are courts utilizing protection order tools correctly? Are judges issuing ex parte orders that trample upon the rights of innocent people before a hearing is held to determine the validity of specific allegations? Is this area of the law an insufficiently regulated “wild frontier”?

From these concepts, questions immediately present themselves. Are protection orders being utilized in oppressive or unexpected ways? Are the factual scenarios involved similar to what the [legislature] envisioned them to be? Are courts utilizing protection order tools correctly? Are judges issuing ex parte orders that trample upon the rights of innocent people before a hearing is held to determine the validity of specific allegations? Is this area of the law an insufficiently regulated “wild frontier”? While how commonly the process is exploited for ulterior motives is a matter of heated dispute, its availability for abuse is plain. The

While how commonly the process is exploited for ulterior motives is a matter of heated dispute, its availability for abuse is plain. The

The news story the epigraph was excerpted from was prompted by a recent murder in Oregon and explores the impotence of restraining orders, in particular to “stop bullets.” Just as shooting sprees inspire reporters to investigate gun legislation, murder victims who had applied for restraining orders that proved worthless inspire reporters to investigate restraining order policies. The presumption, always, is that the law failed.

The news story the epigraph was excerpted from was prompted by a recent murder in Oregon and explores the impotence of restraining orders, in particular to “stop bullets.” Just as shooting sprees inspire reporters to investigate gun legislation, murder victims who had applied for restraining orders that proved worthless inspire reporters to investigate restraining order policies. The presumption, always, is that the law failed.

“For some people it’s more dangerous [to get a restraining order],” said Kim Larson, director for Marion County District Attorney Victim Assistance Division. “Sometimes it makes people really angry, getting served with a restraining order.”

“For some people it’s more dangerous [to get a restraining order],” said Kim Larson, director for Marion County District Attorney Victim Assistance Division. “Sometimes it makes people really angry, getting served with a restraining order.”

Here are two recent headlines that caught my eye: “

Here are two recent headlines that caught my eye: “ Recognize that in these rare instances when perjury statutes are enforced, the motive is political impression management (government face-saving). Everyday claimants who lie to judges are never charged at all, because the victims of their lies (moms, dads,

Recognize that in these rare instances when perjury statutes are enforced, the motive is political impression management (government face-saving). Everyday claimants who lie to judges are never charged at all, because the victims of their lies (moms, dads,  Here’s the reply the email elicited from ABC’s Bob Borzotta: “Hi Larry, I don’t seem to have heard further from her. Sounds like quite a situation….” Cursory validations like this one are the closest thing to solace that victims of chronic legal abuses can expect.

Here’s the reply the email elicited from ABC’s Bob Borzotta: “Hi Larry, I don’t seem to have heard further from her. Sounds like quite a situation….” Cursory validations like this one are the closest thing to solace that victims of chronic legal abuses can expect. The target of a high-conflict person is perpetually on the defensive, trying to recover his or her former life from the unrelenting grasp of a crank with an extreme (and often pathological) investment in eroding that life for self-aggrandizement and -gratification.

The target of a high-conflict person is perpetually on the defensive, trying to recover his or her former life from the unrelenting grasp of a crank with an extreme (and often pathological) investment in eroding that life for self-aggrandizement and -gratification. The ease with which a restraining order is obtained encourages outrageous defamations like these (Larry’s neighbor has sworn out two). Once a high-conflict person sees how readily

The ease with which a restraining order is obtained encourages outrageous defamations like these (Larry’s neighbor has sworn out two). Once a high-conflict person sees how readily

In the spring of 2011, she had been converting her home to a sort of boarding house and brought in tenants, and [between] them they had two cats that constantly prowled, especially the tenant’s. What became very irksome to me was the tenant’s cat creeping into our yard and killing our baby birds, which we always looked forward to in the spring. And the minute I brought it up with her, she pitched a fit, and so did the tenant. So for the first two months of baby bird season, [their] cats killed all our fledglings and the mother songbirds—wrens, cardinals, robins, mockingbirds, towhees, mourning doves, even the hummingbirds, just wiped them out. I finally got in touch with our Animal Services officers, but by that time bird season was over with, and you know something, [she] began going about telling neighbors that I was a disbarred lawyer (a particularly nasty slander). One thing led to another, and finally the tenant with the marauding cat moved away, but the irreparable damage was done, and all through the summer I had been warned by other neighbors that the neighbor from hell was plotting revenge.

In the spring of 2011, she had been converting her home to a sort of boarding house and brought in tenants, and [between] them they had two cats that constantly prowled, especially the tenant’s. What became very irksome to me was the tenant’s cat creeping into our yard and killing our baby birds, which we always looked forward to in the spring. And the minute I brought it up with her, she pitched a fit, and so did the tenant. So for the first two months of baby bird season, [their] cats killed all our fledglings and the mother songbirds—wrens, cardinals, robins, mockingbirds, towhees, mourning doves, even the hummingbirds, just wiped them out. I finally got in touch with our Animal Services officers, but by that time bird season was over with, and you know something, [she] began going about telling neighbors that I was a disbarred lawyer (a particularly nasty slander). One thing led to another, and finally the tenant with the marauding cat moved away, but the irreparable damage was done, and all through the summer I had been warned by other neighbors that the neighbor from hell was plotting revenge.

“

“ The lawyers quoted by reporter, what’s more, refer to criminal cases in which sexual abuse is alleged and, consequently, in which the accused are afforded attorney representation.

The lawyers quoted by reporter, what’s more, refer to criminal cases in which sexual abuse is alleged and, consequently, in which the accused are afforded attorney representation.

Faith in the conceit that restraining orders are minor impingements on defendants’ lives depends on accepting that being falsely, publically, and permanently labeled a stalker or batterer, for example, shouldn’t interfere with a person’s comfort, equanimity, or ability to realize his or her dreams. Such faith is founded, in other words, on the fantastical belief that wrongful vilification won’t exercise a detrimental influence on a person’s mental state, won’t affect his or her familial and social relationships, won’t negatively impact his or her employment and employability, etc.

Faith in the conceit that restraining orders are minor impingements on defendants’ lives depends on accepting that being falsely, publically, and permanently labeled a stalker or batterer, for example, shouldn’t interfere with a person’s comfort, equanimity, or ability to realize his or her dreams. Such faith is founded, in other words, on the fantastical belief that wrongful vilification won’t exercise a detrimental influence on a person’s mental state, won’t affect his or her familial and social relationships, won’t negatively impact his or her employment and employability, etc.

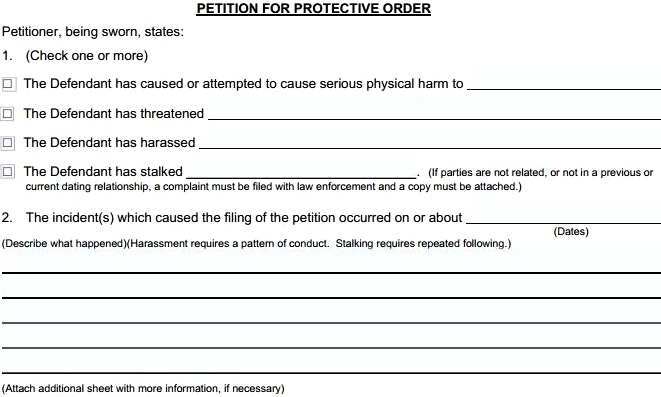

All there is to making allegations on restraining orders is tick boxes and blanks, and there are no bounds imposed upon what allegations can be made. A false applicant merely writes whatever he wants in the spaces provided—and he can use additional pages if he’s feeling inspired. The basis for a woman’s being alleged to be a domestic abuser or even “armed and dangerous” is the unsubstantiated say-so of the petitioner. Can the defendant be a vegetarian single mom or an arthritic, 80-year-old great-grandmother? Sure. The judge who rules on the application won’t have met her and may never even learn what she looks like. She’s just a name.

All there is to making allegations on restraining orders is tick boxes and blanks, and there are no bounds imposed upon what allegations can be made. A false applicant merely writes whatever he wants in the spaces provided—and he can use additional pages if he’s feeling inspired. The basis for a woman’s being alleged to be a domestic abuser or even “armed and dangerous” is the unsubstantiated say-so of the petitioner. Can the defendant be a vegetarian single mom or an arthritic, 80-year-old great-grandmother? Sure. The judge who rules on the application won’t have met her and may never even learn what she looks like. She’s just a name.

Judge Daniel Sanchez issued a restraining order against Letterman based on those allegations. By doing so, it put Letterman on a national list of domestic abusers, gave him a criminal record, took away several of his constitutionally protected rights, and subjected him to criminal prosecution if he contacted Nestler directly or indirectly, or possessed a firearm.

Judge Daniel Sanchez issued a restraining order against Letterman based on those allegations. By doing so, it put Letterman on a national list of domestic abusers, gave him a criminal record, took away several of his constitutionally protected rights, and subjected him to criminal prosecution if he contacted Nestler directly or indirectly, or possessed a firearm. To some degree at least, this understanding restricts all but the mentally ill, who may be delusional, and

To some degree at least, this understanding restricts all but the mentally ill, who may be delusional, and

I’ll give you a for-instance. Let’s say Person A applies for a protection order and claims Person B threatened to rape her and then kill her with a butcher knife.

I’ll give you a for-instance. Let’s say Person A applies for a protection order and claims Person B threatened to rape her and then kill her with a butcher knife. Person A circulates the details she shared with the court, which are embellished and further honed with repetition, among her friends and colleagues over the ensuing days, months, and years.

Person A circulates the details she shared with the court, which are embellished and further honed with repetition, among her friends and colleagues over the ensuing days, months, and years. Scholars, members of the clergy, and practitioners of disciplines like medicine, science, and the law, among others from whom we expect scrupulous truthfulness and a contempt for deception, are furthermore no more above lying (or actively or passively abetting fraud) than anyone else.

Scholars, members of the clergy, and practitioners of disciplines like medicine, science, and the law, among others from whom we expect scrupulous truthfulness and a contempt for deception, are furthermore no more above lying (or actively or passively abetting fraud) than anyone else. M.D., Ph.D., Th.D., LL.D.—no one is above lying, and the fact is the better a liar’s credentials are, the more ably s/he expects to and can pull the wool over the eyes of judges, because in the political arena judges occupy, titles carry weight: might makes right.

M.D., Ph.D., Th.D., LL.D.—no one is above lying, and the fact is the better a liar’s credentials are, the more ably s/he expects to and can pull the wool over the eyes of judges, because in the political arena judges occupy, titles carry weight: might makes right. The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin I’ve quoted goes on at some length to detail the difficulties and complexities that unraveling false claims entails for agents of the FBI. Appreciate then how absurd is the state’s faith that a single judge—or a couple of them—can ascertain the truth of civil restraining order allegations by auditing claims in a hearing or hearings arrived at with no prior information, that last mere minutes, and that are furthermore biased by the preconception that the accused is guilty.

The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin I’ve quoted goes on at some length to detail the difficulties and complexities that unraveling false claims entails for agents of the FBI. Appreciate then how absurd is the state’s faith that a single judge—or a couple of them—can ascertain the truth of civil restraining order allegations by auditing claims in a hearing or hearings arrived at with no prior information, that last mere minutes, and that are furthermore biased by the preconception that the accused is guilty.

The very real if inconvenient truth remains that victims of false allegations made to authorities and the courts present with the same symptoms highlighted in the epigraph: “fear, anxiety, nervousness, self-blame, anger, shame, and difficulty sleeping”—among a host of others. And that’s just the ones who aren’t robbed of everything that made their lives meaningful, including home, property, and family. In the latter case, post-traumatic stress disorder may be the least of their torments. They may be left homeless, penniless, childless, and emotionally scarred.

The very real if inconvenient truth remains that victims of false allegations made to authorities and the courts present with the same symptoms highlighted in the epigraph: “fear, anxiety, nervousness, self-blame, anger, shame, and difficulty sleeping”—among a host of others. And that’s just the ones who aren’t robbed of everything that made their lives meaningful, including home, property, and family. In the latter case, post-traumatic stress disorder may be the least of their torments. They may be left homeless, penniless, childless, and emotionally scarred.

In fact, what it and any number of others’ ordeals show is that when you offer people an easy means to excite drama and conflict, they’ll exploit it.

In fact, what it and any number of others’ ordeals show is that when you offer people an easy means to excite drama and conflict, they’ll exploit it. Her coterie of girlfriends is transposed straight from the halls of high school. They’re less physically favored than the leader of their pack and content to warm themselves in her aura. The adolescent intrigue injects some color into their treadmill lives, and they savor the vicarious thrill of the hunt. The man is a topic of their daily conversation. The women feel young again for a few months, like conspirators in an unconsummated teen crush.

Her coterie of girlfriends is transposed straight from the halls of high school. They’re less physically favored than the leader of their pack and content to warm themselves in her aura. The adolescent intrigue injects some color into their treadmill lives, and they savor the vicarious thrill of the hunt. The man is a topic of their daily conversation. The women feel young again for a few months, like conspirators in an unconsummated teen crush. The life of the man who’d hospitably welcomed the strangers, shaking hands in good faith and doling out mugs of cheer, is trashed: multiple trips to the police precinct to answer false charges and appeals to the court that only invite censure and further abuse. His record, formerly that of an invisible man, becomes hopelessly corrupted. His artistic endeavor, a labor of love that he’d plied himself at for years and on which he’d banked his future joy and financial comfort, is predictably derailed.

The life of the man who’d hospitably welcomed the strangers, shaking hands in good faith and doling out mugs of cheer, is trashed: multiple trips to the police precinct to answer false charges and appeals to the court that only invite censure and further abuse. His record, formerly that of an invisible man, becomes hopelessly corrupted. His artistic endeavor, a labor of love that he’d plied himself at for years and on which he’d banked his future joy and financial comfort, is predictably derailed. A man eyes a younger, attractive woman at work every day. She’s impressed by him, also, and reciprocates his interest. They have a brief sexual relationship that, unknown to her, is actually an extramarital affair, because the man is married. The younger woman, having naïvely trusted him, is crushed when the man abruptly drops her, possibly cruelly, and she then discovers he has a wife. Maybe she openly confronts him at work. Maybe she calls or texts him. Maybe repeatedly. The man, concerned to preserve appearances and his marriage, applies for a restraining order alleging the woman is harassing him, has become fixated on him, is unhinged. As evidence, he provides phone records, possibly dating from the beginning of the affair—or pre-dating it—besides intimate texts and emails. He may also provide tokens of affection she’d given him, like a birthday card the woman signed and other romantic trifles, and represent them as unwanted or even (implicitly) disturbing. “I’m a married man, Your Honor,” he testifies, admitting nothing, “and this woman’s conduct is threatening my marriage, besides my status at work.”

A man eyes a younger, attractive woman at work every day. She’s impressed by him, also, and reciprocates his interest. They have a brief sexual relationship that, unknown to her, is actually an extramarital affair, because the man is married. The younger woman, having naïvely trusted him, is crushed when the man abruptly drops her, possibly cruelly, and she then discovers he has a wife. Maybe she openly confronts him at work. Maybe she calls or texts him. Maybe repeatedly. The man, concerned to preserve appearances and his marriage, applies for a restraining order alleging the woman is harassing him, has become fixated on him, is unhinged. As evidence, he provides phone records, possibly dating from the beginning of the affair—or pre-dating it—besides intimate texts and emails. He may also provide tokens of affection she’d given him, like a birthday card the woman signed and other romantic trifles, and represent them as unwanted or even (implicitly) disturbing. “I’m a married man, Your Honor,” he testifies, admitting nothing, “and this woman’s conduct is threatening my marriage, besides my status at work.”