“Contemplating, undergoing, or having undergone a lawsuit is disruptive. The experience saps energy and distracts the litigant from the normal daily preoccupations that we call ‘life.’ Litigants, who commonly feel alone, isolated, and helpless, are challenged to confront and manage the emotional burden of the legal process. The distress of litigation can be expressed in multiple symptoms: sleeplessness, anger, frustration, humiliation, headaches, difficulty concentrating, loss of self-confidence, indecision, anxiety, despondency: the picture has much in common with the symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).”

—Dr. Larry H. Strasburger (1999)

Prior posts on this blog have considered Legal Abuse Syndrome (LAS), a concept proposed by marriage and family therapist Karin Huffer that has been discounted by the courts as a “novel theory.” This post spotlights a journal monograph published almost 20 years ago by psychiatrist Larry H. Strasburger that unequivocally states Dr. Huffer isn’t wrong and the courts are.

Dr. Strasburger’s comments in “The Litigant-Patient: Mental Health Consequences of Civil Litigation” are based on his having treated the legally abused (who may include anyone who’s been exposed to litigation).

The therapist of a litigant will encounter not only the trauma that produced the lawsuit, but the distress and disruption of litigation as well, including the delays, rehashing and reliving the original trauma, and challenges to honesty and integrity. The patient may come after years of feeling frustrated and thwarted by a system that moves at a snail’s pace, preventing the litigant from putting the issue of the litigation behind him [or her] and “moving on” with life. Gutheil et al. have recently coined the term “critogenic harm” to describe these emotional harms resulting from the legal process itself.

The term “critogenic harm,” by its etymology, refers to the psychic damages that arise from judgment, i.e., the pain and humiliation of being verbally attacked and publicly disparaged.

This, the reader will note, is a blaring clinical denunciation of those self-appointed, armchair authorities who would deny the damages of false prosecution. Nearly two decades after the publication of the journal article this post examines, such deniers are everywhere, including in the mainstream press.

This, the reader will note, is a blaring clinical denunciation of those self-appointed, armchair authorities who would deny the damages of false prosecution. Nearly two decades after the publication of the journal article this post examines, such deniers are everywhere, including in the mainstream press.

The deniers, according to the experts, are talking out of their blowholes. Mere accusation, ignoring the effects of protracted legal battles, drives some to suicide and multitudes more into agoraphobic withdrawal.

The adversarial system is also a threat to the maintenance of personal boundaries. Formal complaints, interrogatories, depositions, public testimony, and cross-examination are intrusive procedures that aggravate feelings previously caused by trauma. Such procedures amplify feelings that the world is an unsafe place, redoubling the litigant’s need to regain a sense of control—often in any way he or she can, including exhibiting characteristic symptoms or defenses. It is not unusual to find entries such as the following in the medical records of litigants: “Janet is hearing voices to cut herself again after talking to her lawyer today.” Similarly, a male plaintiff in a sexual harassment suit threatened violence when he was informed that he was to be deposed, and he required hospitalization.

Exposure to civil process can very literally drive people nuts, and inspire in them urges to commit violence, whether to themselves or others.

Consider Dr. Strasburger’s remarks in the context of restraining order abuse and appreciate that the strains they describe can be compounded by loss of residence (some defendants are left homeless), loss of family, loss of income, loss of employment/career, loss of property, etc. Those so deprived may accordingly become estranged from friends and relations, if not socially ostracized. (They must also live with the consciousness that they’re vulnerable to warrantless arrest at any time.)

Litigants are often further distressed as various members of their support systems “burn out.” Their need for human connection and their need to talk about their experience often exceed the tolerance of family members and friends. Embarrassment and humiliation shrink their social world.

That’s besides the discord and isolation caused by a damning accusation, which may be accepted as fact even by kith and kin. Loyalties may become divided, and the accused may be spurned based on allegations that aren’t true. The sources of outrage to the mind and emotions multiply like cancer cells.

It should come as no surprise then that many who complain of procedural abuse report they’re in therapy. If the costs weren’t prohibitive to most, they might all be. Desolating, as Dr. Strasburger points out, is that even if this were the case, the promise of “healing” isn’t necessarily good. The therapist’s role may be little more than cheerleader.

Psychotherapy for a patient involved in ongoing litigation can take on the aspects of managing a continuing crisis. The therapist, facing this need for crisis management, may be providing support more than insight.

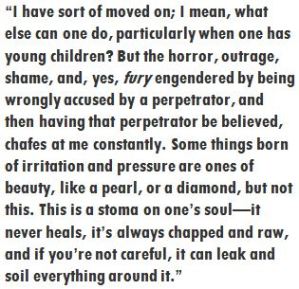

Litigation (or its aftermath) may become consuming; normal, healthy activities are suspended. (One woman this author has corresponded with laments she hasn’t known intimate contact in years; a recent female commenter, alienated from her child, refers to herself as a living homicide.) People may become stuck in a tape loop perpetuated by interminable indeterminacy, insurmountable loss, and a galling sense of injustice.

The legal battle enables people to put their lives on “hold,” thereby avoiding other aspects of their lives (e.g., “How can I be intimate with you when I’m involved in this lawsuit?”). The patient may be so attuned to psycholegal issues and hypotheses that she focuses thereupon in resistance to dealing with significant personal conflict. As a result, she is continually “pleading her case” in the therapy hour.

This cognitive rut exemplifies Legal Abuse Syndrome, and the state may be unending.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*The journal article cited in this post may be introduced to the court by litigants in need of an authoritative voice to validate complaints of pain and suffering induced by fraudulent or vexatious prosecution.