“Ten years ago, about one in 10 domestic violence arrests involved women as defendants. Now, it’s one in five in Michigan and Connecticut, one in four in Vermont and Colorado, and more than one in three in New Hampshire. Public officials are trying to figure out what’s going on. They are especially mystified because, according to [The New York Times], the trend ‘so diverges from the widely accepted estimate that 95 percent of batterers are men.’

“Interesting logic: first, a dogma contradicted by virtually all social science research [namely, 95% of batterers are men] becomes ‘widely accepted.’ Then, when it’s disproved by the facts, the response is to ask what’s wrong with the facts.”

—Cathy Young, “Female Aggression—Domestic Violence’s ‘Dirty Little Secret’” (1999)

What the quoted writer means is that when dogma becomes “widely accepted,” it stays “widely accepted.” Time has proven her right. Fifteen years later, that dogma—men are abusers; women are victims—still predominates.

It gets by with a little help from its friends.

It gets by with a little help from its friends.

Some months ago, a post on this blog responded to research conclusions published this year by Prof. Kelly Behre, director of the UC Davis Law School’s Family Protection and Legal Assistance Clinic.

Among those conclusions was that anecdotal reports of procedural abuses, false allegations, and judicial bias by what she calls FRGs (fathers’ rights groups) have no “legitimate” research studies to back them up and should therefore exert no influence on public policy. They should, according to the professor’s own research, be disregarded.

Last month, it was reported that a George Washington University law professor was awarded a $500,000 grant from the National Institute of Justice (i.e., taxpayers) to “conduct a study in which she hopes to show that family courts across the country have fallen into a pattern of awarding custody” of children to fathers who are “known abusers.”

The professor, Joan Meier, directs the university’s Domestic Violence Project. She’s also the “founder and legal director of the Domestic Violence Legal Empowerment and Appeals Project, a nonprofit that [helps] domestic violence survivors receive pro-bono [legal aid].” Her credentials, you’ll notice, are conspicuously similar to those of Prof. Behre, referenced above.

Consider why Prof. Meier was awarded the grant:

She said researchers can say anecdotally that courts have awarded custody to known abusers or fathers whose [partners or ex-partners] have warned could be abusive to children, but researchers and advocates’ sharing their experiences alone hasn’t yet led to change.

Now consider that fathers’ rights researchers and advocates’ sharing their experiences has also yet to lead to change, and appreciate that those researchers and advocates aren’t being cut half-million-dollar checks to compile research data. What they have to say doesn’t accord with the “widely accepted” dogma; it isn’t popular.

Because their anecdotal reports of false allegations, procedural abuses, and judicial bias don’t have any official research to validate them, they’re to be ignored.

Ignoring those reports, in fact, is essential for a hypothesis like Prof. Meier’s to be tenable. It depends on absolutely denying that those whom the professor calls “known abusers” could be men who’ve been falsely implicated.

Prof. Meier says she expects to use the $500,000 federal grant to conclusively expose gender bias in family court against women—and to do it using a study sample of “over 1,000 court cases from the past 15 years” (a study sample, in other words, of fewer than 2,000 cases).

Prof. Meier says she expects to use the $500,000 federal grant to conclusively expose gender bias in family court against women—and to do it using a study sample of “over 1,000 court cases from the past 15 years” (a study sample, in other words, of fewer than 2,000 cases).

For the professor’s hypothesis to be proven “true,” it just has to be shown that in a significant number of the “over 1,000 cases” reviewed, a father awarded custody of children had previously been accused of abuse.

The researchers hope to debunk “junk science” that mothers make false accusations of abuse to alienate fathers from their sons or daughters, a misconception that Meier said has put many children in danger.

Prof. Meier seems to fail to grasp that the complaint is that mothers successfully “make false accusations of abuse to alienate fathers from their sons and daughters.” Even if her study were to show that child custody is awarded to fathers who’ve been successfully accused of abuse, it wouldn’t necessarily prove that the complaint that false accusations are routine is based on “junk science” (unless by that phrase she means science that hasn’t been government-funded and -audited).

Prof. Meier’s assertion that claims of false allegations are a “misconception,” what’s more, ignores that any number of attorneys who practice family law publicly corroborate that so-called misconception. Some indeed say false allegations to gain the advantage in custody battles are commonplace. These are the attorneys who actually practice in the trenches. Their reports, however, are once again only anecdotal.

Fathers and their advocates who claim false accusations are made don’t, of course, misconceive anything. They know what they know; they’ve lived it. The professor’s use of the word misconception is directed at the “people who count,” that is, the policy-makers. What she means is any credibility they might be disposed to show complainants of procedural abuse is based on a misconception. That misconception, apparently, is that men without law degrees could possibly be telling the truth.

The professor’s assertion that reports of false accusations are “junk science,” furthermore, would seem to advocate for good science, and there’s certainly nothing scientific about prejudicially dismissing those reports offhand. Studies like those proposed by Prof. Meier need to be counterbalanced by studies with opposing hypotheses—and they aren’t.

Meier and her team of legal and statistical experts will create a database of court opinions that she hopes will show a pattern that supports her hypothesis, and will then present it to activists, local courts, and organizations that train judges.

Preservation of dogma is a game of ring-around-a-rosy. Advocacy for what’s widely accepted to be true is lavishly funded, and the resultant “science” may then be used to “train” judges how to rule, further reinforcing the dogma.

(If the context of this policy were Russia instead of the United States, would training still be the word we used to mean influencing judges?)

This is how underhand gets the upper hand, and it’s remarkable how openly this kind of business is transacted. No one bats an eye, because it’s “official.”

Prof. Meier may have the best of intentions. The author of this post has never known anyone whom he would characterize as a domestic violence “survivor.” He has no doubt, however, that there are people who are daily subject to violent cruelty, and if he did know someone like that, he’d be grateful that there were people like Prof. Meier looking out for their interests.

Victims need advocates and defenders.

The reality is, though, that victims of domestic violence have quite an abundance of public and private sympathizers, while victims of abuse of civil and criminal processes legislated to protect battered women and children (including restraining orders) receive little public recognition at all. An agency that calls itself the “National Institute of Justice” shouldn’t play (or pay) favorites. Justice would, in fact, advocate that an equal payout be provided to researchers to study the frequency of fraudulent accusations, which can’t be determined from court rulings, because those rulings are influenced if not dictated by the prevailing dogma.

Hypotheses, it’s been amply observed, tend to incline researchers to find evidence of whatever it was they were looking for in the first place (this is called “confirmation bias” or “myside bias”).

Leora Rosen, a former senior social science analyst at the National Institute of Justice, said [Prof. Meier’s] study is unique because it is transparent about its lack of objectivity and looks at family court rather than criminal court cases. She has partnered with Meier for the study.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

Many of the posts published here in 2014 concern how we talk about violence against women.

Many of the posts published here in 2014 concern how we talk about violence against women. I had a brief but enlightening conversation years ago with a detective in my local county attorney’s office. I called to report perjury (lying to the court) by a restraining order petitioner. He sympathized but said his office was too preoccupied with prosecuting more pressing felonies, like murder, to investigate allegations of perjury.

I had a brief but enlightening conversation years ago with a detective in my local county attorney’s office. I called to report perjury (lying to the court) by a restraining order petitioner. He sympathized but said his office was too preoccupied with prosecuting more pressing felonies, like murder, to investigate allegations of perjury. Those accused in civil court, though, are fish in a barrel. Judges are authorized to decide restraining order cases according to personal whim. There’s no “proof beyond a reasonable doubt” criterion to satisfy, and they know they have the green light to rule however they want.

Those accused in civil court, though, are fish in a barrel. Judges are authorized to decide restraining order cases according to personal whim. There’s no “proof beyond a reasonable doubt” criterion to satisfy, and they know they have the green light to rule however they want.

During the term of their relationship, no reports of any kind of domestic conflict were made to authorities.

During the term of their relationship, no reports of any kind of domestic conflict were made to authorities. back was turned. Since the woman’s knuckles were plainly lacerated from punching glass, no arrest ensued. According to the man’s stepmother, the woman lied similarly to procure a protection order a couple of days later.

back was turned. Since the woman’s knuckles were plainly lacerated from punching glass, no arrest ensued. According to the man’s stepmother, the woman lied similarly to procure a protection order a couple of days later.

The reason why, basically, is that the system likes closure. Once it rules on something, it doesn’t want to think about it again.

The reason why, basically, is that the system likes closure. Once it rules on something, it doesn’t want to think about it again.

With regard to the honest representation of facts in court, however, both accusers and judges fudge (and that’s putting it mildly). Each may frame facts to produce a favored impression.

With regard to the honest representation of facts in court, however, both accusers and judges fudge (and that’s putting it mildly). Each may frame facts to produce a favored impression.

The trial court that heard the restraining order case against Mrs. Harman, and whose backroom judgment was overturned by the North Carolina Court of Appeals, had ruled, “Defendant [Harman] has harassed plaintiffs within the meaning of [N.C. Gen. Stat. §] 50C-1(6) and (7) by knowingly publishing electronic or computerized transmissions directed at plaintiffs that torments, terrorizes, or terrifies plaintiffs and serves no legitimate purpose” (italics added).

The trial court that heard the restraining order case against Mrs. Harman, and whose backroom judgment was overturned by the North Carolina Court of Appeals, had ruled, “Defendant [Harman] has harassed plaintiffs within the meaning of [N.C. Gen. Stat. §] 50C-1(6) and (7) by knowingly publishing electronic or computerized transmissions directed at plaintiffs that torments, terrorizes, or terrifies plaintiffs and serves no legitimate purpose” (italics added). Cindie Harman ultimately won the case against her, a case that should never have been entertained by the court in the first place, but a victory that should have reassured her that freedom of speech in our country is a revered and inviolate privilege has had the opposite effect.

Cindie Harman ultimately won the case against her, a case that should never have been entertained by the court in the first place, but a victory that should have reassured her that freedom of speech in our country is a revered and inviolate privilege has had the opposite effect. Pols and corporations engage in flimflam to win votes and increase profit shares. Science, too, seeks acclaim and profit, and judicial motives aren’t so different. Judges know what’s expected of them, and they know how to interpret information to satisfy expectations.

Pols and corporations engage in flimflam to win votes and increase profit shares. Science, too, seeks acclaim and profit, and judicial motives aren’t so different. Judges know what’s expected of them, and they know how to interpret information to satisfy expectations. Since judges can rule however they want, and since they know that very well, they don’t even have to lie, per se, just massage the facts a little. It’s all about which facts are emphasized and which facts are suppressed, how select facts are interpreted, and whether “fear” can be reasonably inferred from those interpretations. A restraining order ruling can only be construed as “wrong” if it can be demonstrated that it violated statutory law (or the source that that law must answer to:

Since judges can rule however they want, and since they know that very well, they don’t even have to lie, per se, just massage the facts a little. It’s all about which facts are emphasized and which facts are suppressed, how select facts are interpreted, and whether “fear” can be reasonably inferred from those interpretations. A restraining order ruling can only be construed as “wrong” if it can be demonstrated that it violated statutory law (or the source that that law must answer to:  Feminism’s foot soldiers in the blogosphere and on social media, finally, spread the “good word,” and John and Jane Doe believe what they’re told—unless or until they’re torturously disabused of their illusions. Stories like those you’ll find

Feminism’s foot soldiers in the blogosphere and on social media, finally, spread the “good word,” and John and Jane Doe believe what they’re told—unless or until they’re torturously disabused of their illusions. Stories like those you’ll find

The 2012-13

The 2012-13  Granted, survey statistics are probably as comprehensive as it’s practical for them to be, and contrary statistics that these figures are rejoined with by advocates for disenfranchised groups like battered men may themselves be based on surveys of even smaller groups of people. All such studies are subject to sampling error, because there’s no practicable means to interview an entire population, and sampling error is hardly the only error inherent to such studies, which are based on reported facts that may be impossible to substantiate.

Granted, survey statistics are probably as comprehensive as it’s practical for them to be, and contrary statistics that these figures are rejoined with by advocates for disenfranchised groups like battered men may themselves be based on surveys of even smaller groups of people. All such studies are subject to sampling error, because there’s no practicable means to interview an entire population, and sampling error is hardly the only error inherent to such studies, which are based on reported facts that may be impossible to substantiate.

After sitting huddled in a corner and pronouncing, “I want to die,” she rallies and confronts her former lover while he’s conducting a business meeting. Without much prelude, she kicks him in the testicles and bloodies his nose.

After sitting huddled in a corner and pronouncing, “I want to die,” she rallies and confronts her former lover while he’s conducting a business meeting. Without much prelude, she kicks him in the testicles and bloodies his nose. Had the man surreptitiously shot the photos and aired them without her consent, she could have taken him to the cleaners. The courts do more than frown upon that kind of thing, especially when the photos are nudies.

Had the man surreptitiously shot the photos and aired them without her consent, she could have taken him to the cleaners. The courts do more than frown upon that kind of thing, especially when the photos are nudies. The account below, by Rosemary Anderson of Australia, was submitted to the e-petition End Restraining Order Abuses (since terminated by its host) and is highlighted here to show (1) that restraining orders are abused not only by intimates but by neighbors and strangers, (2) that the ease with which they’re applied for entices vexatious litigants (especially once their appetite has been whetted), and (3) that restraining orders are abused in countries other than the United States.

The account below, by Rosemary Anderson of Australia, was submitted to the e-petition End Restraining Order Abuses (since terminated by its host) and is highlighted here to show (1) that restraining orders are abused not only by intimates but by neighbors and strangers, (2) that the ease with which they’re applied for entices vexatious litigants (especially once their appetite has been whetted), and (3) that restraining orders are abused in countries other than the United States. The matter began when we opposed the expansion of their egg farm. We did so through the appropriate channels and in the appropriate manner. They have a CCW on their property and for reasons unknown were allowed to build the egg farm far too close to our boundary and house.

The matter began when we opposed the expansion of their egg farm. We did so through the appropriate channels and in the appropriate manner. They have a CCW on their property and for reasons unknown were allowed to build the egg farm far too close to our boundary and house. She once threatened my employer to get me sacked. I had luckily recorded several previous incidents that proved to my boss the lies they tell. They once took us to court over the boundary fence even though we had evidence in the form of letters and photos. Miraculously they won as they brought the non-professional fencing person with them as a witness. We weren’t given the appropriate notice by the court of their witness and could have selected several witnesses of our own to prove the fencing contractor assisted our neighbours to make a false insurance claim. The summons for this also came 18 months after we had given them what we had considered an appropriate payment. They had cashed the cheque and never contacted us in between to dispute it.

She once threatened my employer to get me sacked. I had luckily recorded several previous incidents that proved to my boss the lies they tell. They once took us to court over the boundary fence even though we had evidence in the form of letters and photos. Miraculously they won as they brought the non-professional fencing person with them as a witness. We weren’t given the appropriate notice by the court of their witness and could have selected several witnesses of our own to prove the fencing contractor assisted our neighbours to make a false insurance claim. The summons for this also came 18 months after we had given them what we had considered an appropriate payment. They had cashed the cheque and never contacted us in between to dispute it. J, a single dad who lives in Texas with his two kids, submitted his story as a comment to the blog in September, prefacing it: “I am writing this to share [it] with the rest of my fellow male victims [who] fall in with the dreaded Crazy.”

J, a single dad who lives in Texas with his two kids, submitted his story as a comment to the blog in September, prefacing it: “I am writing this to share [it] with the rest of my fellow male victims [who] fall in with the dreaded Crazy.” Because it was all complete bullsh*t.

Because it was all complete bullsh*t. He gave me the number of an attorney friend who worked in Little Rock. Next thing I knew, I’m having to fax or email every record I kept that shows my whereabouts on that day: gas receipts, store receipts, etc. I had to get a list of movies that I watched from the video download company we use. Cell phone calls. Text messages. (By the way, they really do monitor those. They can pinpoint your exact location, but you have to send a written request.) All of this to prove I was not there. Once I gave that attorney everything, he told me he would go to court that day and ask for an extension of 60 days. And I would still have to show up in Arkansas. Sh*t!

He gave me the number of an attorney friend who worked in Little Rock. Next thing I knew, I’m having to fax or email every record I kept that shows my whereabouts on that day: gas receipts, store receipts, etc. I had to get a list of movies that I watched from the video download company we use. Cell phone calls. Text messages. (By the way, they really do monitor those. They can pinpoint your exact location, but you have to send a written request.) All of this to prove I was not there. Once I gave that attorney everything, he told me he would go to court that day and ask for an extension of 60 days. And I would still have to show up in Arkansas. Sh*t! The day of the court hearing came. I drove out of state to be there. She actually showed in up in court that day. I suspect she didn’t expect I would show. The judge called out our docket. She sat on one side of the courtroom. My attorney and I sat on the other.

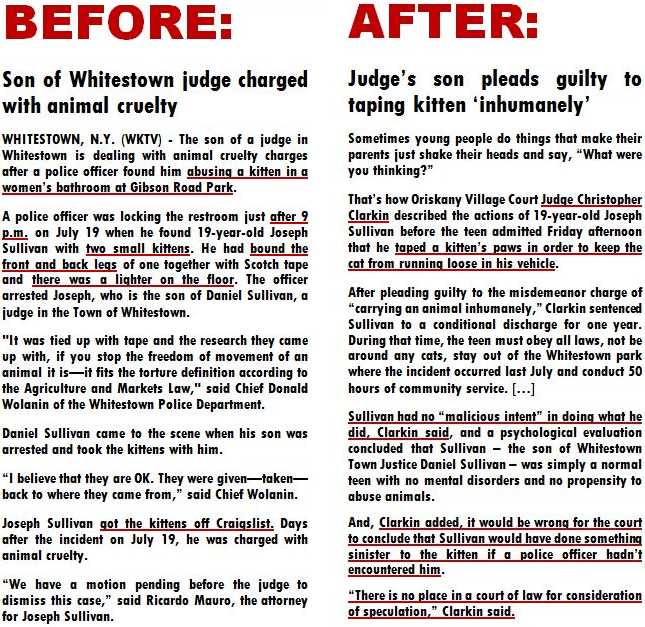

The day of the court hearing came. I drove out of state to be there. She actually showed in up in court that day. I suspect she didn’t expect I would show. The judge called out our docket. She sat on one side of the courtroom. My attorney and I sat on the other. Journalists who recognize the harm of facile or false allegations invariably focus on

Journalists who recognize the harm of facile or false allegations invariably focus on  The implications of restraining orders, what’s more, are generic. There’s no specific charge associated with them. They’re catchalls that categorically imply everything sordid, violent, and creepy. They most urgently suggest stalking, violence, and sexual deviance.

The implications of restraining orders, what’s more, are generic. There’s no specific charge associated with them. They’re catchalls that categorically imply everything sordid, violent, and creepy. They most urgently suggest stalking, violence, and sexual deviance.

I bonded with a client recently while wrestling a tough job to conclusion. I’ll call him “Joe.” Joe and I were talking in his backyard, and he confided to me that his next-door neighbor was “crazy.” She’d reported him to the police “about a 100 times,” he said, including for listening to music after dark on his porch.

I bonded with a client recently while wrestling a tough job to conclusion. I’ll call him “Joe.” Joe and I were talking in his backyard, and he confided to me that his next-door neighbor was “crazy.” She’d reported him to the police “about a 100 times,” he said, including for listening to music after dark on his porch.

It gets by with a little help from its friends.

It gets by with a little help from its friends. Prof. Meier says she expects to use the $500,000 federal grant to conclusively expose gender bias in family court against women—and to do it using a study sample of “over 1,000 court cases from the past 15 years” (a study sample, in other words, of fewer than 2,000 cases).

Prof. Meier says she expects to use the $500,000 federal grant to conclusively expose gender bias in family court against women—and to do it using a study sample of “over 1,000 court cases from the past 15 years” (a study sample, in other words, of fewer than 2,000 cases).

Some recent posts on this blog have touched on what might be called the five magic words, because their utterance may be all that’s required of a petitioner to obtain a restraining order. The five magic words are these: “I’m afraid for my life.”

Some recent posts on this blog have touched on what might be called the five magic words, because their utterance may be all that’s required of a petitioner to obtain a restraining order. The five magic words are these: “I’m afraid for my life.” Gamesmanship in this arena is both bottom-up and top-down. Liars hustle judges…and judges hustle liars along.

Gamesmanship in this arena is both bottom-up and top-down. Liars hustle judges…and judges hustle liars along.

A presumption of people—including even

A presumption of people—including even  People on the outside of the restraining order process imagine that the phrase false accusations refers to elaborately contrived frame-ups. Frame-ups certainly occur, but they’re mostly improvised. We’re talking about processes that are mere minutes in duration (that includes the follow-up hearings that purport to give defendants the chance to refute the allegations against them).

People on the outside of the restraining order process imagine that the phrase false accusations refers to elaborately contrived frame-ups. Frame-ups certainly occur, but they’re mostly improvised. We’re talking about processes that are mere minutes in duration (that includes the follow-up hearings that purport to give defendants the chance to refute the allegations against them). Judge Stump quickly signed the order, and the judge and mamma hustled Linda into a hospital, telling her it was for an appendicitis operation. Linda was then sterilized without her knowledge. Two years later, Linda married a Leo Sparkman and discovered that she had been sterilized without her knowledge. The Sparkmans proceeded to sue mamma, mamma’s attorney, the doctors, the hospital, and Judge Stump, alleging a half-dozen constitutional violations.

Judge Stump quickly signed the order, and the judge and mamma hustled Linda into a hospital, telling her it was for an appendicitis operation. Linda was then sterilized without her knowledge. Two years later, Linda married a Leo Sparkman and discovered that she had been sterilized without her knowledge. The Sparkmans proceeded to sue mamma, mamma’s attorney, the doctors, the hospital, and Judge Stump, alleging a half-dozen constitutional violations.

Buncombe County, North Carolina, where

Buncombe County, North Carolina, where  She says he’s “barked like a dog” at her, recruited “mentally challenged adults” to harass her while shopping, and mooned her friends. She says he’s cyberstalked her, too, besides hacking into her phone and computer.

She says he’s “barked like a dog” at her, recruited “mentally challenged adults” to harass her while shopping, and mooned her friends. She says he’s cyberstalked her, too, besides hacking into her phone and computer. My son’s girlfriend…filed a domestic abuse CPO [civil protection order] against my son, again telling him that he shouldn’t have left her. He hasn’t been served yet—they keep missing him. She calls my son constantly, stringing him along with the idea that she “might” let it go. He’s taking her out to eat, giving her money, staying the night with her. Hoping that she’ll let it go. All that and yet two hearing dates for him have come and gone with her showing up at both his hearings asking for a continuance because he hasn’t been served.

My son’s girlfriend…filed a domestic abuse CPO [civil protection order] against my son, again telling him that he shouldn’t have left her. He hasn’t been served yet—they keep missing him. She calls my son constantly, stringing him along with the idea that she “might” let it go. He’s taking her out to eat, giving her money, staying the night with her. Hoping that she’ll let it go. All that and yet two hearing dates for him have come and gone with her showing up at both his hearings asking for a continuance because he hasn’t been served. That includes control of the truth. Some cases of blackmail this author has been informed of were instances of the parties accused knowing something about their accusers that their accusers didn’t want to get around (usually criminal activity). When the guilty parties no longer trusted that coercion would ensure that those who had the goods on them would keep quiet, they filed restraining orders against them alleging abuse, which instantly discredited anything the people they accused might disclose about their activities.

That includes control of the truth. Some cases of blackmail this author has been informed of were instances of the parties accused knowing something about their accusers that their accusers didn’t want to get around (usually criminal activity). When the guilty parties no longer trusted that coercion would ensure that those who had the goods on them would keep quiet, they filed restraining orders against them alleging abuse, which instantly discredited anything the people they accused might disclose about their activities. A recent NPR story reports that dozens of students who’ve been accused of rape are suing their universities. They allege they were denied due process and fair treatment by college investigative committees, that is, that they were “railroaded” (and publicly humiliated and reviled). The basis for a suit alleging civil rights violations, then, might also exist (that is, independent of claims of material privation). Certainly most or all restraining order defendants and many domestic violence defendants are “railroaded” and subjected to public shaming and social rejection unjustly.

A recent NPR story reports that dozens of students who’ve been accused of rape are suing their universities. They allege they were denied due process and fair treatment by college investigative committees, that is, that they were “railroaded” (and publicly humiliated and reviled). The basis for a suit alleging civil rights violations, then, might also exist (that is, independent of claims of material privation). Certainly most or all restraining order defendants and many domestic violence defendants are “railroaded” and subjected to public shaming and social rejection unjustly. Undertaking a venture like coordinating a class action is beyond the resources of this writer, but anyone with the gumption to try and transform words into action is welcome to post a notice here.

Undertaking a venture like coordinating a class action is beyond the resources of this writer, but anyone with the gumption to try and transform words into action is welcome to post a notice here.

The scales of justice are tipped from the start.

The scales of justice are tipped from the start. The savvy observer will note that suspicion is the motive determiner of liability at all levels. Suspicion informs judicial disposition, subsequent police response to claims of violation, and of course interpretation by third parties, including employers (judges trust accusers, and everyone else trusts judges). Emphatically worthy of remark is that

The savvy observer will note that suspicion is the motive determiner of liability at all levels. Suspicion informs judicial disposition, subsequent police response to claims of violation, and of course interpretation by third parties, including employers (judges trust accusers, and everyone else trusts judges). Emphatically worthy of remark is that  From these concepts, questions immediately present themselves. Are protection orders being utilized in oppressive or unexpected ways? Are the factual scenarios involved similar to what the [legislature] envisioned them to be? Are courts utilizing protection order tools correctly? Are judges issuing ex parte orders that trample upon the rights of innocent people before a hearing is held to determine the validity of specific allegations? Is this area of the law an insufficiently regulated “wild frontier”?

From these concepts, questions immediately present themselves. Are protection orders being utilized in oppressive or unexpected ways? Are the factual scenarios involved similar to what the [legislature] envisioned them to be? Are courts utilizing protection order tools correctly? Are judges issuing ex parte orders that trample upon the rights of innocent people before a hearing is held to determine the validity of specific allegations? Is this area of the law an insufficiently regulated “wild frontier”? While how commonly the process is exploited for ulterior motives is a matter of heated dispute, its availability for abuse is plain. The

While how commonly the process is exploited for ulterior motives is a matter of heated dispute, its availability for abuse is plain. The