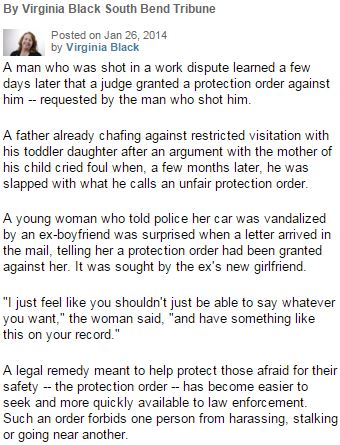

Most restraining orders are issued ex parte, that is, based exclusively on the testimony of the accuser. Making hyped, skewed, or false allegations against someone who’s not there to contradict them, and making those allegations persuasive, isn’t hard. Hearings to finalize orders based on ex parte rulings, furthermore, may begin and end in 10 minutes.

At no stage of the process do allegations meet with eagle-eyed scrutiny.

This shouldn’t be news to anyone, nor should it be news that the effects of picknose adjudications are far-reaching. Based on them, citizens are publicly humiliated and may be deprived of access to their children and property besides denied jobs. Proximal effects of these consequences are stress, emotional turmoil, depression, and disease. (Restraining orders are also a foot in the door from which vexatious litigants can persecute the accused relentlessly, aggravating these effects manifold.)

The accused expect these results to be obvious to judges, and they expect consciousness of them to influence judges’ decisions. They expect judges to care about the truth and to care equally about the lives of those who stand before them. Judges, however, aren’t boy scouts, philosophers, or social workers. They’re just people performing a job. They clock their eight and hit the gate like sanitation workers do—and they may not perceive their job very differently.

There is a difference, though. How judges are to perform their job is prescribed by the law. The indifference of the law is the problem.

Laws concerning restraining orders were hastily slapped together decades ago, and their evolution has been informed by very narrow priorities (mostly prescribed by feminist advocates and VAWA). None of these priorities considers the rights or welfare of the accused. Restraining order law is “women’s law,” and the only historical imperative has been to process, prohibit, punish, and permanently brand purported abusers in the name of protecting those who are “politically disadvantaged.”

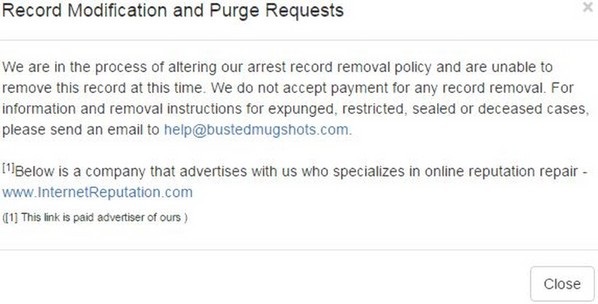

As recent posts have stressed, restraining orders are public records that staunchly resist revision or expungement. While convicted felons may be able to have their criminal records erased, citizens accused on restraining order petitions, even ones that have been dismissed (“thrown out”), must wear their labels forever.

To be accused is to stay accused.

This injustice won a fresh objector recently whose story is telling. I won’t identify him, because he intends to tell the story himself sometime soon, and he hopes to report a happy conclusion. This man made headlines last year when he successfully appealed a restraining order against him in his state’s supreme court. The order was vacated, and that should have been an end on it.

Not long ago, he says, he and his girlfriend were detained by a customs and border official when they attempted to reenter the country after going on a cruise. The dismissed restraining order raised some kind of red flag (in the mind of the official, anyhow). The man wasn’t seriously inconvenienced, and as an American citizen, he faced no risk of being barred from the country.

What was forcibly brought to his attention, though, is that a very dead order of the court still hounded him months after it should have been laid to rest.

The man is an entrepreneur who works for himself, but he’s now cognizant of the potential harm a record like this could have on anyone who’s employed in the public or private sector who’s subject to a thorough background check. The record that got him detained didn’t say “vacated” or “void” or any such thing. It showed, in fact, as current.

That’s because tidy-up isn’t mandated by law; only this is: “Process, prohibit, punish, and permanently brand purported abusers.” Nobody in the system cares what happens afterwards, because no one in the system has to. It’s on to the next “abuser.”

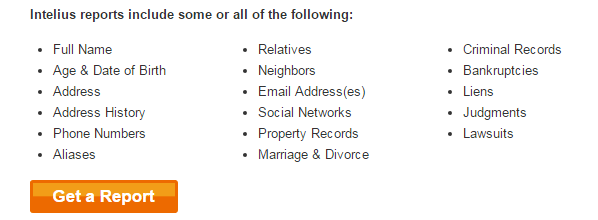

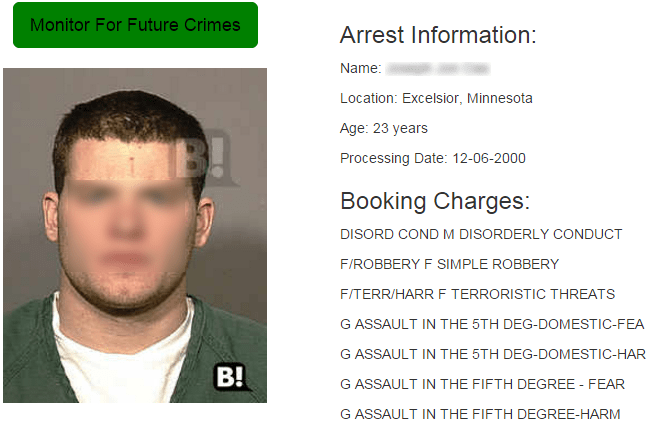

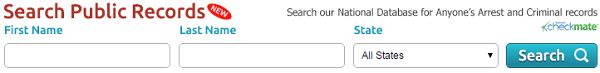

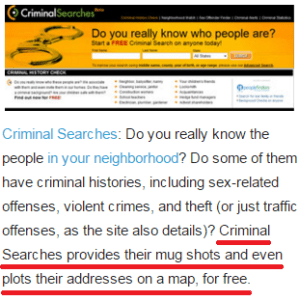

This highlights a broader fact about restraining orders. They’re prejudicial, and because they’re pumped into statewide and national databases, they’re subject to free interpretation by anyone in the system—or anyone with access to the public record…which is anyone.

Summary:

- A judge interprets some superficial claims made by a complainant and enters a “preliminary” (ex parte) order. This is then permanently entered into the public record, including into state and federal registries.

- The order may be finalized, or it may be “tossed.” Either way, the initial judge’s (five-minute) impression is preserved.

- Any other cog in the system, whether a clerk of the court, police officer, or other public official, can see this record and freely interpret its significance.

- Any private party, what’s more (e.g., an employer, a loan officer, a landlord, a student, a client, a girl- or boyfriend, a child’s school administrator, etc.), is also invited to freely interpret the significance of an order that may bear a title as fatal to the accused’s popularity and prospects as “emergency protective order for stalking and sexual assault.” (Even if such an order is tossed after the defendant is afforded the chance to defend him- or herself—or because the plaintiff voluntarily had the order dismissed—the permanent record still says, “emergency protective order for stalking and sexual assault,” and it says it right next to the defendant’s name.)

What might be called cruel and unusual punishment isn’t acknowledged by our government as unjust or even unfair.

Copyright © 2016 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*When the writer of this post was first accused in 2006, he inquired with two clerks at the Pima County Superior Courthouse about where to file a brief to a judge. The male of the pair, upon hearing what the matter was about, fixed him with a knowing look and gratuitously remarked, “She wants you to stay away from her, right?” My accuser, a married woman who deceived multiple judges, was someone I had only ever encountered outside of my own house (where she nightly hung around in the dark). Pococurante orders of the court license any arrogant twit to form whatever conclusion s/he wants…and to pronounce that conclusion with righteous contempt.