“The restraining order law is perhaps the second most unconstitutional abomination in our legal system, after our so-called child protection (DSS) laws. The restraining order process is designed to allow an order to be issued very easily, and to be appealed, stopped, or vacated only with the utmost difficulty….

“The motives for this law are legion. First, it makes the Commonwealth a bunch of money by allowing it to leverage massive Federal grants. It makes feminist victim groups a lot of money by providing millions in state and federal grants to stop ‘domestic violence.’ It makes lawyers and court personnel a lot money as they administer the Godzilla-sized system they have built to deal with these orders. It makes police a lot of money, as they are able to leverage huge grants for arrests of violators. It makes mental health professionals a lot of money dealing with the mandatory therapy always required in these situations. It makes thousands of social workers a lot of money providing social services for all the families that the law destroys. It makes dozens of men’s batterers programs a lot of money providing anger management treatment ordered by courts in these proceedings.”

—Attorney Gregory Hession

The aggregation of money is not only the dirty little secret behind the perpetuation of constitutionally insupportable restraining order laws that are a firmly rooted institution in this country and in many others across the globe; money is also what ensures that very few mainstream public figures ever voice dissenting views on the legitimacy and justice of restraining orders.

Lawyers and judges I’ve talked to readily own their disenchantment with restraining order policy and don’t hesitate to acknowledge its malodor. It’s very rare, though, to find a quotation in print from an officer of the court that says as much. Job security is as important to them as it is to the next guy, and restraining orders are a political hot potato, because the feminist lobby is a powerful one and one that’s not distinguished for its temperateness or receptiveness to compromise or criticism.

Lawyers and judges I’ve talked to readily own their disenchantment with restraining order policy and don’t hesitate to acknowledge its malodor. It’s very rare, though, to find a quotation in print from an officer of the court that says as much. Job security is as important to them as it is to the next guy, and restraining orders are a political hot potato, because the feminist lobby is a powerful one and one that’s not distinguished for its temperateness or receptiveness to compromise or criticism.

I’m not employed as an investigative journalist. I’m a would-be kids’ humorist who earns his crust as a manual laborer and sometime editor of student essays and flier copy. My available research tools are a beater laptop and Google.

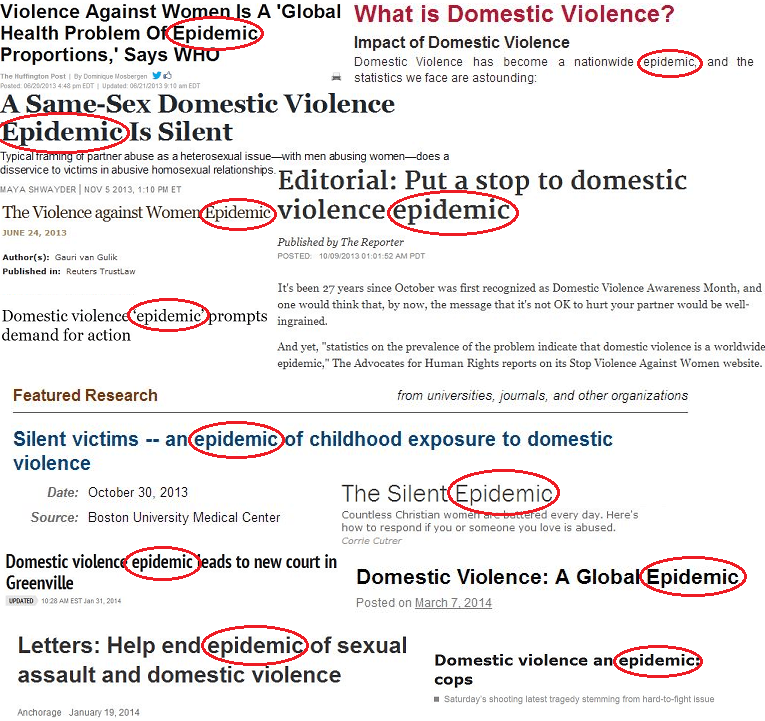

What a casual search engine query returned to me in terms of numbers and government rhetoric that substantiate the arguments made in this post’s epigraph is this (emphases in the excerpts below are added):

Grants to Encourage Arrest Policies and Enforcement of Protection Orders Program

Number: 16.590

Agency: Department of Justice

Office: Violence Against Women Office

Program Information

Authorization:

Violence Against Women and Department of Justice Reauthorization Act of 2005, Title I, Section 102, Public Law 109-162; Violence Against Women Act of 2000, Public Law 106-386; Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, 42 U.S.C. 3796hh, as amended.

Objectives:

To encourage States, Indian tribal governments, State and local courts (including juvenile courts), tribal courts, and units of local government to treat domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking as serious violations of criminal law.

Types of Assistance:

PROJECT GRANTS

Uses and Use Restrictions:

Grants may be used for the following statutory program purposes: (1) To implement proarrest programs and policies in police departments, including policies for protection order violations. (2) To develop policies, educational programs, protection order registries, and training in police departments to improve tracking of cases involving domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking. Policies, educational programs, protection order registries, and training described in this paragraph shall incorporate confidentiality, and privacy protections for victims of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking. (3) To centralize and coordinate police enforcement, prosecution, or judicial responsibility for domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking cases in teams or units of police officers, prosecutors, parole and probation officers, or judges. (4) To coordinate computer tracking systems to ensure communication between police, prosecutors, parole and probation officers, and both criminal and family courts. (5) To strengthen legal advocacy service programs for victims of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking, including strengthening assistance to such victims in immigration matters. (6) To educate judges in criminal and civil courts (including juvenile courts) about domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking and to improve judicial handling of such cases. (7) To provide technical assistance and computer and other equipment to police departments, prosecutors, courts, and tribal jurisdictions to facilitate the widespread enforcement of protection orders, including interstate enforcement, enforcement between States and tribal jurisdictions, and enforcement between tribal jurisdictions. (8) To develop or strengthen policies and training for police, prosecutors, and the judiciary in recognizing, investigating, and prosecuting instances of domestic violence and sexual assault against older individuals (as defined in section 3002 of this title) and individuals with disabilities (as defined in section 12102(2) of this title). (9) To develop State, tribal, territorial, or local policies, procedures, and protocols for preventing dual arrests and prosecutions in cases of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking, and to develop effective methods for identifying the pattern and history of abuse that indicates which party is the actual perpetrator of abuse. (10) To plan, develop and establish comprehensive victim service and support centers, such as family justice centers, designed to bring together victim advocates from non-profit, non-governmental victim services organizations, law enforcement officers, prosecutors, probation officers, governmental victim assistants, forensic medical professionals, civil legal attorneys, chaplains, legal advocates, representatives from community-based organizations and other relevant public or private agencies or organizations into one centralized location, in order to improve safety, access to services, and confidentiality for victims and families. Although funds may be used to support the colocation of project partners under this paragraph, funds may not support construction or major renovation expenses or activities that fall outside of the scope of the other statutory purpose areas. (11) To develop and implement policies and training for police, prosecutors, probation and parole officers, and the judiciary in recognizing, investigating, and prosecuting instances of sexual assault, with an emphasis on recognizing the threat to the community for repeat crime perpetration by such individuals. (12) To develop, enhance, and maintain protection order registries. (13) To develop human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing programs for sexual assault perpetrators and notification and counseling protocols.

Applicant Eligibility:

Grants are available to States, Indian tribal governments, units of local government, and State, tribal, territorial, and local courts.

Beneficiary Eligibility:

Beneficiaries include criminal and tribal justice practitioners, domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault and stalking victim advocates, and other service providers who respond to victims of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking.

Credentials/Documentation:

According to 42 U.S.C. § 3796hh(c), to be eligible to receive funding through this Program, applicants must:

(1) certify that their laws or official policies–

(A) encourage or mandate arrests of domestic violence offenders based on probable cause that an offense has been committed; and

(B) encourage or mandate arrest of domestic violence offenders who violate the terms of a valid and outstanding protection order;

(2) demonstrate that their laws, policies, or practices and their training programs

discourage dual arrests of offender and victim;

(3) certify that their laws, policies, or practices prohibit issuance of mutual restraining orders of protection except in cases where both spouses file a claim and the court makes detailed findings of fact indicating that both spouses acted primarily as aggressors and that neither spouse acted primarily in self-defense; and

(4) certify that their laws, policies, and practices do not require, in connection with the prosecution of any misdemeanor or felony domestic violence offense, or in connection with the filing, issuance, registration, or service of a protection order, or a petition for a protection order, to protect a victim of sexual assault, domestic violence, or stalking, that the victim bear the costs associated with the filing of criminal charges against the offender, or the costs associated with the filing, issuance, registration, or service of a warrant, protection order, petition for a protection order, or witness subpoena, whether issued inside or outside the State, Tribal or local jurisdiction; and

(5) certify that their laws, policies, or practices ensure that—

(A) no law enforcement officer, prosecuting officer or other government official shall ask or require an adult, youth, or child victim of a sex offense as defined under Federal, Tribal, State, Territorial, or local law to submit to a polygraph examination or other truth telling device as a condition for proceeding with the investigation of such an offense; and

(B) the refusal of a victim to submit to an examination described in subparagraph (A) shall not prevent the investigation of the offense.

Range and Average of Financial Assistance:

Range: $176,735–$1,167,713

Average: $571,816.

That’s a pretty fair lump of dough, and what it’s for—among other things as you’ll notice if you read between the lines—is to “educate” our police officers and judges about what their priorities should be.

Note that eligibility requirements for receiving grants through this program include (1) the prohibition of counter-injunctions, that is, restraining orders counter-filed by people who have had restraining orders issued against them; (2) the issuance of restraining orders at no cost to their applicants; and (3) the acceptance of plaintiffs’ allegations on faith. Note, also, that one of the objectives of this program is to promote the establishment of registries that make the names of restraining order recipients conveniently available to the general public.

The legitimacy of these grants (“grants” having a more benevolent resonance to it than “inducements”) goes largely uncontested, because who’s going to say they’re “for” crimes against women and children?

The rhetorical design of all things related to the administration of restraining orders and the laws that authorize them is ingenious and, on its surface, unimpeachable.

By everyone, that is, except the victims of a process that is as manifestly and multifariously crooked as a papier-mâché flagpole.

Paying authorities and the judiciary to assume a preferential disposition toward restraining order applicants completely undermines the principles of impartiality and fair and equal treatment that our system of laws was established upon.

It isn’t cash this process needs. It’s change.

Copyright © 2013 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

Plainly restraining orders have put no dent in the problem. What’s more, it’s possible they’ve made it worse.

Plainly restraining orders have put no dent in the problem. What’s more, it’s possible they’ve made it worse. Feminism doesn’t appeal to or cultivate sympathy; it largely strives to chastise and dominate, which can only foster misogyny.

Feminism doesn’t appeal to or cultivate sympathy; it largely strives to chastise and dominate, which can only foster misogyny. On balance, the curative value of restraining orders is null if not negative. Per capita, that is, they do more harm than good. And the impact of each instance of abuse of power is chain-reactive, because every victim has relatives and friends who may be jarred by its reverberations.

On balance, the curative value of restraining orders is null if not negative. Per capita, that is, they do more harm than good. And the impact of each instance of abuse of power is chain-reactive, because every victim has relatives and friends who may be jarred by its reverberations.

tenets of law, like impartiality, diligent deliberation, and

tenets of law, like impartiality, diligent deliberation, and  A theme that emerges upon consideration of

A theme that emerges upon consideration of  It’s ironic that the focus of those who should be most sensitized to injustice is so narrow. Ironic, moreover, is that “emotional abuse” is frequently a component of state definitions of domestic violence. The state recognizes the harm of emotional violence done in the home but conveniently regards the same conduct as harmless when it uses the state as its instrument.

It’s ironic that the focus of those who should be most sensitized to injustice is so narrow. Ironic, moreover, is that “emotional abuse” is frequently a component of state definitions of domestic violence. The state recognizes the harm of emotional violence done in the home but conveniently regards the same conduct as harmless when it uses the state as its instrument. Here’s yet another irony. Too often the perspectives of those who decry injustices are partisan. Feminists themselves are liable to see only one side.

Here’s yet another irony. Too often the perspectives of those who decry injustices are partisan. Feminists themselves are liable to see only one side. Now consider the motives of false allegations and their certain and potential effects: isolation, termination of employment and impediment to or negation of employability, inaccessibility to children (who are used as leverage), and being forced to live on limited means (while possibly being required under threat of punishment to provide spousal and child support) and perhaps being left with no home to furnish or automobile to drive at all.

Now consider the motives of false allegations and their certain and potential effects: isolation, termination of employment and impediment to or negation of employability, inaccessibility to children (who are used as leverage), and being forced to live on limited means (while possibly being required under threat of punishment to provide spousal and child support) and perhaps being left with no home to furnish or automobile to drive at all.

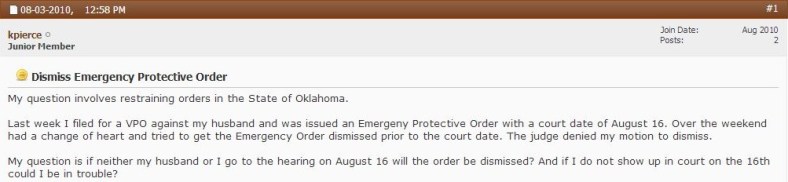

Notable, contrariwise, however, is that the respondent discourages the petitioner of the restraining order, who’s admitted to proceeding impulsively, from following through with her expressed intention to rectify an act that may have been motivated by spite. The respondent is the executive director of

Notable, contrariwise, however, is that the respondent discourages the petitioner of the restraining order, who’s admitted to proceeding impulsively, from following through with her expressed intention to rectify an act that may have been motivated by spite. The respondent is the executive director of

The biggest challenge to sensitizing people to abusive restraining order policies that are readily and pervasively exploited by malicious litigants can be summed up in a single word: sex.

The biggest challenge to sensitizing people to abusive restraining order policies that are readily and pervasively exploited by malicious litigants can be summed up in a single word: sex.

Note that the odds of its being accurate, assuming all conditions are equal, may be only slightly better than a coin flip’s.

Note that the odds of its being accurate, assuming all conditions are equal, may be only slightly better than a coin flip’s. Restraining orders are understood to be issued to “sickos.” Nobody hears “restraining order” and thinks “Little Rascal.”

Restraining orders are understood to be issued to “sickos.” Nobody hears “restraining order” and thinks “Little Rascal.”

No argument here.

No argument here. to the procurement of restraining orders, which are presumed to be sought by those in need of protection.

to the procurement of restraining orders, which are presumed to be sought by those in need of protection. Such hearings are far more perfunctory than probative. Basically a judge is just looking for a few cue words to run with and may literally be satisfied by a plaintiff’s saying, “I’m afraid.” (Talk show host

Such hearings are far more perfunctory than probative. Basically a judge is just looking for a few cue words to run with and may literally be satisfied by a plaintiff’s saying, “I’m afraid.” (Talk show host  Those who profit politically and monetarily by the misery inflicted through court processes that are easily abused by the “morally unencumbered” love all this conflict and misdirected rage, which only ensure that these corrupt processes continue to thrive.

Those who profit politically and monetarily by the misery inflicted through court processes that are easily abused by the “morally unencumbered” love all this conflict and misdirected rage, which only ensure that these corrupt processes continue to thrive.

“If we did prosecute perjurers, there’d be no resources left for putting dangerous people behind bars…so we’ll prosecute the people perjurers falsely accuse of being dangerous”—as analysis of most of the arguments made in defense of domestic violence and restraining order policies reveals, the reasoning is circular and smells foul. It’s in fact unreasoned “reasoning” that’s really just something to say to distract attention from unflattering truths that don’t win elections, federal grants, popular esteem, or political favor. So entrenched are these policies and so megalithic (and lucrative) that rhetoric like this actually passes for satisfactory when it’s used by someone in a crisp suit with a crisper title.

“If we did prosecute perjurers, there’d be no resources left for putting dangerous people behind bars…so we’ll prosecute the people perjurers falsely accuse of being dangerous”—as analysis of most of the arguments made in defense of domestic violence and restraining order policies reveals, the reasoning is circular and smells foul. It’s in fact unreasoned “reasoning” that’s really just something to say to distract attention from unflattering truths that don’t win elections, federal grants, popular esteem, or political favor. So entrenched are these policies and so megalithic (and lucrative) that rhetoric like this actually passes for satisfactory when it’s used by someone in a crisp suit with a crisper title. What this blog and

What this blog and

I’ve recently observed that several jobs in the legal and government spheres are ones people with so-called psychopathic traits are said to gravitate toward: lawyer, police officer, and civil servant (judges are both lawyers and civil servants). Other “

I’ve recently observed that several jobs in the legal and government spheres are ones people with so-called psychopathic traits are said to gravitate toward: lawyer, police officer, and civil servant (judges are both lawyers and civil servants). Other “ That’s why I’m particularly impressed when I encounter writers whose literary protests are not only controlled but very lucid and balanced. One such writer maintains a blog titled

That’s why I’m particularly impressed when I encounter writers whose literary protests are not only controlled but very lucid and balanced. One such writer maintains a blog titled  This means defendants can be denied access to the family pet(s), besides.

This means defendants can be denied access to the family pet(s), besides.

Those most dramatically impacted by restraining order abuse, its victims, are typically only heard to peep and grumble here and there.

Those most dramatically impacted by restraining order abuse, its victims, are typically only heard to peep and grumble here and there.

Following Tylenol’s being tampered with in 1981, everything from diced onions to multivitamins requires a safety seal. Naive trust was violated, and legislators responded.

Following Tylenol’s being tampered with in 1981, everything from diced onions to multivitamins requires a safety seal. Naive trust was violated, and legislators responded.

A person who obtains a fraudulent restraining order or otherwise abuses the system to bring you down with false allegations does so because you didn’t bend to his or her will like you were supposed to do.

A person who obtains a fraudulent restraining order or otherwise abuses the system to bring you down with false allegations does so because you didn’t bend to his or her will like you were supposed to do.

I’ve recently tried to debunk some of the

I’ve recently tried to debunk some of the

What most people don’t get about restraining orders is how much they have in common with Mad Libs. You know, that party game where you fill in random nouns, verbs, and modifiers to concoct a zany story? What petitioners fill in the blanks on restraining order applications with is typically more deliberate but may be no less farcical.

What most people don’t get about restraining orders is how much they have in common with Mad Libs. You know, that party game where you fill in random nouns, verbs, and modifiers to concoct a zany story? What petitioners fill in the blanks on restraining order applications with is typically more deliberate but may be no less farcical.

Lawyers and judges I’ve talked to readily own their disenchantment with restraining order policy and don’t hesitate to acknowledge its malodor. It’s very rare, though, to find a quotation in print from an officer of the court that says as much. Job security is as important to them as it is to the next guy, and restraining orders are a political hot potato, because the feminist lobby is a powerful one and one that’s not distinguished for its temperateness or receptiveness to compromise or criticism.

Lawyers and judges I’ve talked to readily own their disenchantment with restraining order policy and don’t hesitate to acknowledge its malodor. It’s very rare, though, to find a quotation in print from an officer of the court that says as much. Job security is as important to them as it is to the next guy, and restraining orders are a political hot potato, because the feminist lobby is a powerful one and one that’s not distinguished for its temperateness or receptiveness to compromise or criticism.