“Rejecting the trial court’s concentration solely on the most recent event, we held it to be ‘essential that the court avoid an unduly narrow focus. One cannot determine whether [a CPO is appropriate] by simply examining the most recent episode. Rather, the judge must be apprised of the entire mosaic.’”

—District of Columbia Court of Appeals

The acronym CPO in the epigraph stands for “civil protection order.” Consider what the epigraph says. If it surprises you, that’s probably because you’ve been a restraining order defendant or known someone who was. Almost 20 years after the publication of this opinion by the court, judges continue to take little or no interest in the history of relationship conflict. “The most recent episode” (i.e., whatever a complainant happens to be complaining about) is all judges typically concern themselves with. (Allegations from the accused of chronic abuse by the complainant may be completely disregarded; trial judges prefer their facts in black-and-white.)

Bloggers and columnists like Jonathan Turley and Eugene Volokh, both of them legal scholars, are Johnny-on-the-spot when it comes to reporting groundbreaking court rulings.

Yet so occult are restraining order trials (i.e., hidden from view) that there’s no one who’s aware of merely significant findings in this arena of law. Nor is there anyone who monitors whether significant or even groundbreaking findings exercise any actual influence on everyday trial practice.

The restraining order process is unpoliced.

Law Prof. Aaron Caplan has remarked (2013):

As with family law, civil harassment law has a way of encouraging some judges to dispense freewheeling, Solomonic justice according to their visions of proper behavior and the best interests of the parties. Judges’ legal instincts are not helped by the accelerated and abbreviated procedures required by the statutes. The parties are rarely represented by counsel, and ex parte orders are encouraged, which means courts may not hear the necessary facts and legal arguments. Very few civil harassment cases lead to appeals, let alone appeals with published opinions. As a result, civil harassment law tends to operate with a shortage of two things we ordinarily rely upon to ensure accurate decision-making by trial courts: the adversary system and appellate review.

The areas of law in which rulings are commonly complained of as outrageous—domestic violence law, family law, and restraining order law—are essentially “backroom.” They’re unregulated.

The author of BuncyBlawg.com, a former trial attorney who is the best monitor this writer knows of, yesterday shared a link to a 1999 ruling out of the Capitol that underscores the disconnect between how the higher courts say restraining order trials should be conducted and how they’re actually conducted.

In Tyree v. Evans, the appellate judges rejected practices that are still common today, if not universally standard. Not only is it the case, as Prof. Caplan has asserted, that appellate review of restraining order rulings is lacking; the few appellate rulings that emerge may be ignored.

Here’s a summary of Tyree v. Evans:

In this case of alleged domestic violence involving an unmarried couple, the trial judge issued a one-year civil protection order (CPO) against the defendant, Bernard Tyree, without permitting Tyree’s attorney to cross-examine the complainant, Juanita Evans. Observing that unlike Mr. Tyree, Ms. Evans was not represented by counsel, the judge stated that Tyree “has no right to confront or cross-examine her. This is a civil proceeding.”

The District of Columbia Court of Appeals ruled to vacate the order (i.e., to “toss” it) on these bases: “Under American practice…adversarial cross-examination is a right of the party against whom a witness is offered”; “the judge may not preclude the opposing party from exercising the basic rights of a litigant.”

The defendant on the restraining order was denied the right to cross-examine the prosecuting witness (i.e., the plaintiff). The court judged this to be inconsistent with basic civil procedure, and it made this determination almost 20 years ago.

Nevertheless, it’s still common (if not standard) practice today to deny a defendant the right to cross-examine his or her accuser. Instead, the court may (may) allow a defendant to ask questions of the judge who may (may) relay those questions to the plaintiff.

Alternatively, a judge may simply refuse to listen to a defense that s/he feels is unworthy. There is no oversight of this arena of law; what trial judges say goes.

In Tyree v. Evans, the court determined that “interrogation by the judge is not a sufficient substitute for cross-examination….” Seven years after this ruling, when the writer of this post was in court, he was informed that he could not question his accuser but could only pose questions through the judge.

Even when bad practice is denounced by the court, nothing changes.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*Restraining order appellants who were denied the opportunity to cross-examine their accusers may cite conclusions of the court like those introduced in this post as grounds for dismissal of the orders against them.

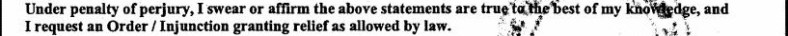

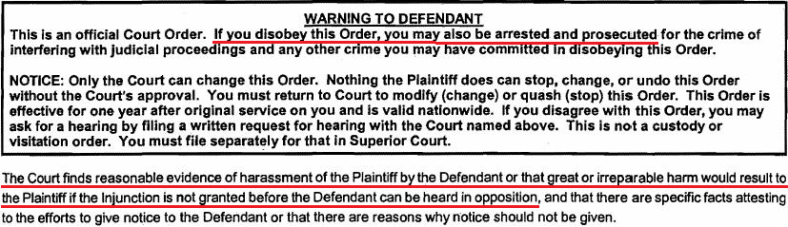

Appreciate that the court’s basis for issuing the document capped with the “Warning” pictured above is nothing more than some allegations from the order’s plaintiff, allegations scrawled on a form and typically made orally to a judge in four or five minutes.

Appreciate that the court’s basis for issuing the document capped with the “Warning” pictured above is nothing more than some allegations from the order’s plaintiff, allegations scrawled on a form and typically made orally to a judge in four or five minutes.