This blog was inspired by firsthand experience with judicial iniquity.

This blog was inspired by firsthand experience with judicial iniquity.

Its author has never been accused of violence, doesn’t sanction violence except in self-defense or the defense of others, and has been a practicing vegetarian since adolescence. I have, what’s more, hazarded my life going to the aid of non-human animals. In one instance, I lost the use of my hand for a year; in another, I had various of my bones fractured or crushed, and that damage is permanent.

Although I’ve never been accused of violence (only its threat: “Will I be attacked?”), I know very well I might have been accused of violence, and I know with absolute certainty that the false accusation could have stuck—and easily—regardless of my ethical scruples and what my commitment to them has cost me.

Who people are, what they stand for, and what they have or haven’t done—these make no difference when they’re falsely fingered by a dedicated accuser who alleges abuse or fear.

This is wrong, categorically wrong, and the only arguments for maintenance of the status quo are ones that favor a particular interest group or political persuasion, which means those arguments contravene the rule of constitutional law.

Justice that isn’t equitable isn’t justice. Arguments for the perpetuation of the same ol’ same ol’, then, are nonstarters. Dogma continues to prevail, however, by distraction: “a majority of rapes go unreported,” “most battered women suffer in silence,” “domestic violence is epidemic” (men have it coming to them). Invocation of social ills that have no bearing on individual cases has determined public policy and conditioned judicial impulse.

Justice that isn’t equitable isn’t justice. Arguments for the perpetuation of the same ol’ same ol’, then, are nonstarters. Dogma continues to prevail, however, by distraction: “a majority of rapes go unreported,” “most battered women suffer in silence,” “domestic violence is epidemic” (men have it coming to them). Invocation of social ills that have no bearing on individual cases has determined public policy and conditioned judicial impulse.

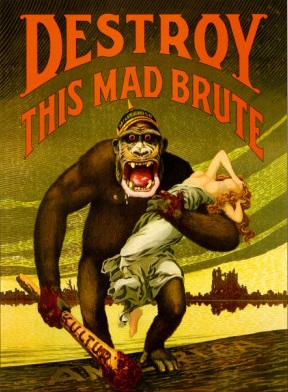

Injustice, no surprise, arouses animosity; injustice that confounds lives, moreover, provokes rage, predictably and justly. This post looks at how that rage is severed from its roots—injustice—and held aloft like a monster’s decapitated head to be scorned and reviled.

I first learned of the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) from a research paper published by Law Professor Kelly Behre this year that equates men’s rights activism with hatemongering. I later heard this position of the SPLC’s reiterated in an NPR piece about the first International Conference on Men’s Issues.

Injustice, it should be noted preliminarily, is of no lesser interest to women than to men. Both men and women are abused by laws and practices purportedly established to protect women, laws and practices that inform civil, criminal, and family court proceedings.

Groups like the SPLC, however, represent opposition to these laws and practices as originating strictly from MRAs, or men’s rights activists, whom they dismiss as senseless haters. This lumping is characteristic of the smoke-and-mirrors tactics favored by those allied to various women’s causes. They limn the divide as being between irrationally irate men and battered women’s advocates (or between “abusers” and “victims”).

They don’t necessarily deny there’s a middle ground; they just ignore it. Consequently, they situate themselves external to it. There are no women’s rights activists (“WRAs”?) who mediate between extremes. They’re one of the extremes.

They don’t necessarily deny there’s a middle ground; they just ignore it. Consequently, they situate themselves external to it. There are no women’s rights activists (“WRAs”?) who mediate between extremes. They’re one of the extremes.

I’m a free agent, and this blog isn’t associated with any group, though the above-mentioned law professor, Dr. Behre, identifies the blog in her paper as authored by an “FRG” (father’s rights group), based on my early on citing the speculative statistic that as many as 80% of restraining orders are said to be “unnecessary” or based on false claims, which may in fact be true even if Dr. Behre finds the estimate unscientific. (Survey statistics cited by women’s advocates and represented as fact are no more ascertainably conclusive; they’re only perceived as more “legitimate.”)

SAVE Services, one of the nonprofits to cite a 2008 West Virginia study from which the roughly 80% or 4-out-of-5 statistic is derived, is characterized by the SPLC and consequently Dr. Behre as being on a par with a “hate group,” like white supremacists. It isn’t, and the accusation is silly, besides nasty. This kind of facile association, though, has proven to be very effective at neutering opposing perspectives, even moderate and disciplined ones. Journalists, the propagators of information, may more readily credit a nonprofit like the SPLC, which identifies itself as a law center and has a longer and more illustrious history, than it may SAVE, which is also a nonprofit. The SPLC’s motto, “Fighting Hate • Teaching Tolerance • Seeking Justice,” could just as aptly be applied to SAVE’s basic endeavor.

On the left is a symbol for the Ku Klux Klan; on the right, the symbol for feminist solidarity. The images have common features, and their juxtaposition suggests the two groups are linked. This little gimmick exemplifies how guilt by association works.

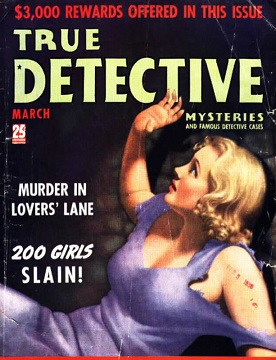

The SPLC’s rhetorical strategy, an m.o. typical of those with the same political orientation, is as follows: (1) scour websites and forums in the “manosphere” for soundbites that include heated denunciations and misogynistic epithets, (2) assemble a catalog of websites and forums that espouse or can be said to sympathize with extremist convictions or positions, and (3) lump all websites and forums speaking to discrimination against men together and collectively label them misogynistic. Thus reports like these: “Misogyny: The Sites” and “Men’s Rights Movement Spreads False Claims about Women.”

Cherry-picked posts, positions, and quotations are highlighted; arguments are desiccated into ideological blurbs punctuated with indelicate words; and all voices are mashed up into a uniform, sinister hiss.

The SPLC’s explicit criticism may not be unwarranted, but coming as it does from a “law center” whose emblem is a set of balanced scales, that criticism is fairly reproached for its carelessness and chauvinism. There are no qualifications to suggest there’s any merit to the complaints that the SPLC criticizes.

The SPLC’s criticism, rather, invites its audience to conclude that complaints of feminist-motivated iniquities in the justice system are merely hate rhetoric, which makes the SPLC’s criticism a PC version of hate rhetoric. The bias is just reversed.

Complaints from the “[mad]manosphere” that are uncivil (or even rabid) aren’t necessarily invalid. The knee-jerk  urge to denounce angry rhetoric betrays how conditioned we’ve been by the prevailing dogma. No one is outraged that people may be falsely implicated as stalkers, batterers, and child molesters in public trials. Nor is anyone outraged that the falsely accused may consequently be forbidden access to their children, jackbooted from their homes, denied employment, and left stranded and stigmatized. This isn’t considered abusive, let alone acknowledged for the social obscenity that it is. “Abusive” is when the falsely implicated who’ve been typified as brutes and sex offenders and who’ve been deprived of everything that meant anything to them complain about it.

urge to denounce angry rhetoric betrays how conditioned we’ve been by the prevailing dogma. No one is outraged that people may be falsely implicated as stalkers, batterers, and child molesters in public trials. Nor is anyone outraged that the falsely accused may consequently be forbidden access to their children, jackbooted from their homes, denied employment, and left stranded and stigmatized. This isn’t considered abusive, let alone acknowledged for the social obscenity that it is. “Abusive” is when the falsely implicated who’ve been typified as brutes and sex offenders and who’ve been deprived of everything that meant anything to them complain about it.

Impolitely. (What would Mrs. Grundy say?)

There’s no question the system is corrupt, and the SPLC doesn’t say it isn’t. It reinforces the corruption by caricaturing the opposition as a horde of frothing woman-haters.

Enter Betty Krachey, a Tennessee woman who knows court corruption intimately. Betty launched a website and e-petition this year to urge her state to prosecute false accusers after being issued an injunction that labeled her a domestic abuser and that she alleges was based on fraud and motivated by spite and greed. Ask her if she’s angry about that, and she’ll probably say you’re damn right. (Her life has nothing to do with whether “most battered women suffer in silence” or “a majority of rapes go unreported,” and those facts in no way justify her being railroaded and menaced by the state.)

I made this website to make people aware of Order of Protections & restraining orders being taken out on innocent people based on false allegations so a vindictive person can gain control with the help of authorities. The false accusers are being allowed to walk away and pay NO consequences for swearing to lies to get these orders! […]

I know that, in my case, the judge didn’t know me. Even though I talked to the magistrate the day BEFORE the order of protection was taken out on me & I told him what I heard [he] had planned for me. They didn’t know that I might have superpowers where I could cause him bodily harm 4 1/2 miles away. SO they had no choice but to protect [him] from me. BUT when they found out this order of protection was based on lies that he swore to, and he used the county in a cunning and vindictive way to get me kicked out of the house – HE SHOULD HAVE HAD TO PAY SOME CONSEQUENCES INSTEAD OF BEING ALLOWED TO WALK AWAY LIKE NOTHING HAPPENED!!!!

Seems like a fair point, and it’s fair points like Betty’s that get talked around and over. There are no legal advocates with the SPLC’s clout looking out for people like Betty; they’re busy making claims like hers seem anomalous, trivial, or crackpot.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*Betty reports she’s been in conference with one of her state’s representatives and has been told she has “a good chance at getting this law changed,” albeit too belatedly to affect her own circumstances. Says Betty, “I still want the law changed to hold false accusers accountable!” Amen to that.

During the term of their relationship, no reports of any kind of domestic conflict were made to authorities.

During the term of their relationship, no reports of any kind of domestic conflict were made to authorities. back was turned. Since the woman’s knuckles were plainly lacerated from punching glass, no arrest ensued. According to the man’s stepmother, the woman lied similarly to procure a protection order a couple of days later.

back was turned. Since the woman’s knuckles were plainly lacerated from punching glass, no arrest ensued. According to the man’s stepmother, the woman lied similarly to procure a protection order a couple of days later.

The reason why, basically, is that the system likes closure. Once it rules on something, it doesn’t want to think about it again.

The reason why, basically, is that the system likes closure. Once it rules on something, it doesn’t want to think about it again.

Judge Stump quickly signed the order, and the judge and mamma hustled Linda into a hospital, telling her it was for an appendicitis operation. Linda was then sterilized without her knowledge. Two years later, Linda married a Leo Sparkman and discovered that she had been sterilized without her knowledge. The Sparkmans proceeded to sue mamma, mamma’s attorney, the doctors, the hospital, and Judge Stump, alleging a half-dozen constitutional violations.

Judge Stump quickly signed the order, and the judge and mamma hustled Linda into a hospital, telling her it was for an appendicitis operation. Linda was then sterilized without her knowledge. Two years later, Linda married a Leo Sparkman and discovered that she had been sterilized without her knowledge. The Sparkmans proceeded to sue mamma, mamma’s attorney, the doctors, the hospital, and Judge Stump, alleging a half-dozen constitutional violations.

People falsely alleged to be abusers on restraining order petitions, particularly men, are treated like brutes, sex offenders, and scum by officers of the court and its staff, besides by authorities and any number of others. Some report their own relatives remain suspicious—often based merely on finger-pointing that’s validated by some judge in a few-minute procedure (and that’s when relatives aren’t the ones making the false allegations).

People falsely alleged to be abusers on restraining order petitions, particularly men, are treated like brutes, sex offenders, and scum by officers of the court and its staff, besides by authorities and any number of others. Some report their own relatives remain suspicious—often based merely on finger-pointing that’s validated by some judge in a few-minute procedure (and that’s when relatives aren’t the ones making the false allegations). So…slanders and libels made by abuse of court process aren’t actionable, slanders and libels that completely sunder the lives of the wrongly accused, who can’t even get them expunged from their records to simply reset their fractured lives to zero.

So…slanders and libels made by abuse of court process aren’t actionable, slanders and libels that completely sunder the lives of the wrongly accused, who can’t even get them expunged from their records to simply reset their fractured lives to zero. My son’s girlfriend…filed a domestic abuse CPO [civil protection order] against my son, again telling him that he shouldn’t have left her. He hasn’t been served yet—they keep missing him. She calls my son constantly, stringing him along with the idea that she “might” let it go. He’s taking her out to eat, giving her money, staying the night with her. Hoping that she’ll let it go. All that and yet two hearing dates for him have come and gone with her showing up at both his hearings asking for a continuance because he hasn’t been served.

My son’s girlfriend…filed a domestic abuse CPO [civil protection order] against my son, again telling him that he shouldn’t have left her. He hasn’t been served yet—they keep missing him. She calls my son constantly, stringing him along with the idea that she “might” let it go. He’s taking her out to eat, giving her money, staying the night with her. Hoping that she’ll let it go. All that and yet two hearing dates for him have come and gone with her showing up at both his hearings asking for a continuance because he hasn’t been served. That includes control of the truth. Some cases of blackmail this author has been informed of were instances of the parties accused knowing something about their accusers that their accusers didn’t want to get around (usually criminal activity). When the guilty parties no longer trusted that coercion would ensure that those who had the goods on them would keep quiet, they filed restraining orders against them alleging abuse, which instantly discredited anything the people they accused might disclose about their activities.

That includes control of the truth. Some cases of blackmail this author has been informed of were instances of the parties accused knowing something about their accusers that their accusers didn’t want to get around (usually criminal activity). When the guilty parties no longer trusted that coercion would ensure that those who had the goods on them would keep quiet, they filed restraining orders against them alleging abuse, which instantly discredited anything the people they accused might disclose about their activities. A recent NPR story reports that dozens of students who’ve been accused of rape are suing their universities. They allege they were denied due process and fair treatment by college investigative committees, that is, that they were “railroaded” (and publicly humiliated and reviled). The basis for a suit alleging civil rights violations, then, might also exist (that is, independent of claims of material privation). Certainly most or all restraining order defendants and many domestic violence defendants are “railroaded” and subjected to public shaming and social rejection unjustly.

A recent NPR story reports that dozens of students who’ve been accused of rape are suing their universities. They allege they were denied due process and fair treatment by college investigative committees, that is, that they were “railroaded” (and publicly humiliated and reviled). The basis for a suit alleging civil rights violations, then, might also exist (that is, independent of claims of material privation). Certainly most or all restraining order defendants and many domestic violence defendants are “railroaded” and subjected to public shaming and social rejection unjustly. Undertaking a venture like coordinating a class action is beyond the resources of this writer, but anyone with the gumption to try and transform words into action is welcome to post a notice here.

Undertaking a venture like coordinating a class action is beyond the resources of this writer, but anyone with the gumption to try and transform words into action is welcome to post a notice here.

The scales of justice are tipped from the start.

The scales of justice are tipped from the start. The savvy observer will note that suspicion is the motive determiner of liability at all levels. Suspicion informs judicial disposition, subsequent police response to claims of violation, and of course interpretation by third parties, including employers (judges trust accusers, and everyone else trusts judges). Emphatically worthy of remark is that

The savvy observer will note that suspicion is the motive determiner of liability at all levels. Suspicion informs judicial disposition, subsequent police response to claims of violation, and of course interpretation by third parties, including employers (judges trust accusers, and everyone else trusts judges). Emphatically worthy of remark is that  From these concepts, questions immediately present themselves. Are protection orders being utilized in oppressive or unexpected ways? Are the factual scenarios involved similar to what the [legislature] envisioned them to be? Are courts utilizing protection order tools correctly? Are judges issuing ex parte orders that trample upon the rights of innocent people before a hearing is held to determine the validity of specific allegations? Is this area of the law an insufficiently regulated “wild frontier”?

From these concepts, questions immediately present themselves. Are protection orders being utilized in oppressive or unexpected ways? Are the factual scenarios involved similar to what the [legislature] envisioned them to be? Are courts utilizing protection order tools correctly? Are judges issuing ex parte orders that trample upon the rights of innocent people before a hearing is held to determine the validity of specific allegations? Is this area of the law an insufficiently regulated “wild frontier”? While how commonly the process is exploited for ulterior motives is a matter of heated dispute, its availability for abuse is plain. The

While how commonly the process is exploited for ulterior motives is a matter of heated dispute, its availability for abuse is plain. The

The news story the epigraph was excerpted from was prompted by a recent murder in Oregon and explores the impotence of restraining orders, in particular to “stop bullets.” Just as shooting sprees inspire reporters to investigate gun legislation, murder victims who had applied for restraining orders that proved worthless inspire reporters to investigate restraining order policies. The presumption, always, is that the law failed.

The news story the epigraph was excerpted from was prompted by a recent murder in Oregon and explores the impotence of restraining orders, in particular to “stop bullets.” Just as shooting sprees inspire reporters to investigate gun legislation, murder victims who had applied for restraining orders that proved worthless inspire reporters to investigate restraining order policies. The presumption, always, is that the law failed.

“For some people it’s more dangerous [to get a restraining order],” said Kim Larson, director for Marion County District Attorney Victim Assistance Division. “Sometimes it makes people really angry, getting served with a restraining order.”

“For some people it’s more dangerous [to get a restraining order],” said Kim Larson, director for Marion County District Attorney Victim Assistance Division. “Sometimes it makes people really angry, getting served with a restraining order.”

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

Consider that if millions of people (counting both false accusers and the falsely accused) are every year having it impressed upon them by judges that lying is not only okay but profitable, then social ethics is taking a pretty significant hit—and at a pretty significant rate.

Consider that if millions of people (counting both false accusers and the falsely accused) are every year having it impressed upon them by judges that lying is not only okay but profitable, then social ethics is taking a pretty significant hit—and at a pretty significant rate. “

“ A false restraining order litigant with a malicious yen may leave a courthouse shortly after entering it having gained sole entitlement to a residence, attendant properties, and children, possibly while displacing blame from him- or herself for misconduct, and having enjoyed the reward of an authority figure’s undivided attention won at the expense of his or her victim.

A false restraining order litigant with a malicious yen may leave a courthouse shortly after entering it having gained sole entitlement to a residence, attendant properties, and children, possibly while displacing blame from him- or herself for misconduct, and having enjoyed the reward of an authority figure’s undivided attention won at the expense of his or her victim.

“

“ The lawyers quoted by reporter, what’s more, refer to criminal cases in which sexual abuse is alleged and, consequently, in which the accused are afforded attorney representation.

The lawyers quoted by reporter, what’s more, refer to criminal cases in which sexual abuse is alleged and, consequently, in which the accused are afforded attorney representation.

Faith in the conceit that restraining orders are minor impingements on defendants’ lives depends on accepting that being falsely, publically, and permanently labeled a stalker or batterer, for example, shouldn’t interfere with a person’s comfort, equanimity, or ability to realize his or her dreams. Such faith is founded, in other words, on the fantastical belief that wrongful vilification won’t exercise a detrimental influence on a person’s mental state, won’t affect his or her familial and social relationships, won’t negatively impact his or her employment and employability, etc.

Faith in the conceit that restraining orders are minor impingements on defendants’ lives depends on accepting that being falsely, publically, and permanently labeled a stalker or batterer, for example, shouldn’t interfere with a person’s comfort, equanimity, or ability to realize his or her dreams. Such faith is founded, in other words, on the fantastical belief that wrongful vilification won’t exercise a detrimental influence on a person’s mental state, won’t affect his or her familial and social relationships, won’t negatively impact his or her employment and employability, etc.

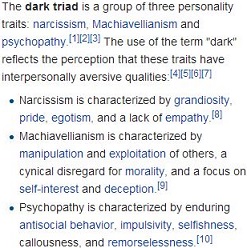

It turns out there’s a sexy phrase for the collective personality traits exhibited by manipulators of this sort: the “

It turns out there’s a sexy phrase for the collective personality traits exhibited by manipulators of this sort: the “

The Dark Triad traits should be associated with preferring casual relationships of one kind or another. Narcissism in particular should be associated with desiring a variety of relationships. Narcissism is the most social of the three, having an approach orientation towards friends (Foster & Trimm, 2008) and an externally validated ‘ego’ (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008). By preferring a range of relationships, narcissists are better suited to reinforce their sense of self. Therefore, although collectively the Dark Triad traits will be correlated with preferring different casual sex relationships, after controlling for the shared variability among the three traits, we expect that narcissism will correlate with preferences for one-night stands and friend[s]-with-benefits.

The Dark Triad traits should be associated with preferring casual relationships of one kind or another. Narcissism in particular should be associated with desiring a variety of relationships. Narcissism is the most social of the three, having an approach orientation towards friends (Foster & Trimm, 2008) and an externally validated ‘ego’ (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008). By preferring a range of relationships, narcissists are better suited to reinforce their sense of self. Therefore, although collectively the Dark Triad traits will be correlated with preferring different casual sex relationships, after controlling for the shared variability among the three traits, we expect that narcissism will correlate with preferences for one-night stands and friend[s]-with-benefits. What we’re talking about in the context of abuse of restraining orders are people who exploit others and then exploit legal process as a convenient means to discard them when they’re through (while whitewashing their own behaviors, procuring additional narcissistic supply in the forms of attention and special treatment, and possibly exacting a measure of revenge if they feel they’ve been criticized or contemned).

What we’re talking about in the context of abuse of restraining orders are people who exploit others and then exploit legal process as a convenient means to discard them when they’re through (while whitewashing their own behaviors, procuring additional narcissistic supply in the forms of attention and special treatment, and possibly exacting a measure of revenge if they feel they’ve been criticized or contemned). I tend to manipulate others to get my way.

I tend to manipulate others to get my way.

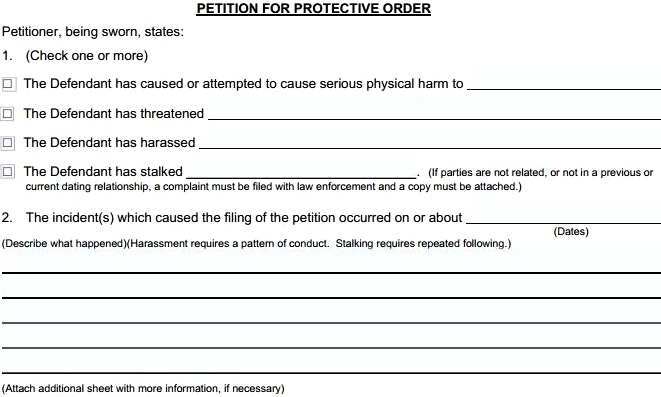

All there is to making allegations on restraining orders is tick boxes and blanks, and there are no bounds imposed upon what allegations can be made. A false applicant merely writes whatever he wants in the spaces provided—and he can use additional pages if he’s feeling inspired. The basis for a woman’s being alleged to be a domestic abuser or even “armed and dangerous” is the unsubstantiated say-so of the petitioner. Can the defendant be a vegetarian single mom or an arthritic, 80-year-old great-grandmother? Sure. The judge who rules on the application won’t have met her and may never even learn what she looks like. She’s just a name.

All there is to making allegations on restraining orders is tick boxes and blanks, and there are no bounds imposed upon what allegations can be made. A false applicant merely writes whatever he wants in the spaces provided—and he can use additional pages if he’s feeling inspired. The basis for a woman’s being alleged to be a domestic abuser or even “armed and dangerous” is the unsubstantiated say-so of the petitioner. Can the defendant be a vegetarian single mom or an arthritic, 80-year-old great-grandmother? Sure. The judge who rules on the application won’t have met her and may never even learn what she looks like. She’s just a name.

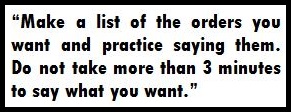

The same impulsive emotional reasoning exemplified by this foot-stamping is what’s suggested by the search terms that introduce this post (to which I could have appended thousands more of a similar nature).

The same impulsive emotional reasoning exemplified by this foot-stamping is what’s suggested by the search terms that introduce this post (to which I could have appended thousands more of a similar nature). The thrust of today’s mainstream ideological feminism is to blame, subjugate, and punish, not unify. Feminism has betrayed itself.

The thrust of today’s mainstream ideological feminism is to blame, subjugate, and punish, not unify. Feminism has betrayed itself. Restraining orders are by and large sought impulsively—in the millions every year. Both motives and the engine that generates them are virtually automatic.

Restraining orders are by and large sought impulsively—in the millions every year. Both motives and the engine that generates them are virtually automatic.

Judge Daniel Sanchez issued a restraining order against Letterman based on those allegations. By doing so, it put Letterman on a national list of domestic abusers, gave him a criminal record, took away several of his constitutionally protected rights, and subjected him to criminal prosecution if he contacted Nestler directly or indirectly, or possessed a firearm.

Judge Daniel Sanchez issued a restraining order against Letterman based on those allegations. By doing so, it put Letterman on a national list of domestic abusers, gave him a criminal record, took away several of his constitutionally protected rights, and subjected him to criminal prosecution if he contacted Nestler directly or indirectly, or possessed a firearm. To some degree at least, this understanding restricts all but the mentally ill, who may be delusional, and

To some degree at least, this understanding restricts all but the mentally ill, who may be delusional, and

I’ll give you a for-instance. Let’s say Person A applies for a protection order and claims Person B threatened to rape her and then kill her with a butcher knife.

I’ll give you a for-instance. Let’s say Person A applies for a protection order and claims Person B threatened to rape her and then kill her with a butcher knife. Person A circulates the details she shared with the court, which are embellished and further honed with repetition, among her friends and colleagues over the ensuing days, months, and years.

Person A circulates the details she shared with the court, which are embellished and further honed with repetition, among her friends and colleagues over the ensuing days, months, and years.

Note that the odds of its being accurate, assuming all conditions are equal, may be only slightly better than a coin flip’s.

Note that the odds of its being accurate, assuming all conditions are equal, may be only slightly better than a coin flip’s. Restraining orders are understood to be issued to “sickos.” Nobody hears “restraining order” and thinks “Little Rascal.”

Restraining orders are understood to be issued to “sickos.” Nobody hears “restraining order” and thinks “Little Rascal.”

No argument here.

No argument here. to the procurement of restraining orders, which are presumed to be sought by those in need of protection.

to the procurement of restraining orders, which are presumed to be sought by those in need of protection. Such hearings are far more perfunctory than probative. Basically a judge is just looking for a few cue words to run with and may literally be satisfied by a plaintiff’s saying, “I’m afraid.” (Talk show host

Such hearings are far more perfunctory than probative. Basically a judge is just looking for a few cue words to run with and may literally be satisfied by a plaintiff’s saying, “I’m afraid.” (Talk show host

Restraining orders are maliciously abused—not sometimes, but often. Typically this is done in heat to hurt or hurt back, to shift blame for abusive misconduct, or to gain the upper hand in a conflict that may have far-reaching consequences.

Restraining orders are maliciously abused—not sometimes, but often. Typically this is done in heat to hurt or hurt back, to shift blame for abusive misconduct, or to gain the upper hand in a conflict that may have far-reaching consequences.

A recent male respondent to this blog, for example, reports encountering an ex while out with his kids and being lured over, complimented, etc. (“Here, boy! Come!”), following which the woman reported to the police that she was terribly alarmed by the encounter and, while brandishing a restraining order application she’d filled out, had the man charged with stalking. Though the meeting was recorded on store surveillance video and was unremarkable, the woman had no difficulty persuading a male officer that she responded to the man in a friendly manner because she was afraid of him (a single father out with his two little kids). The man also reports (desperately and apologetic for being a “bother”) that he and his children have been baited and threatened on Facebook, including by a female friend of his ex’s and by strangers.

A recent male respondent to this blog, for example, reports encountering an ex while out with his kids and being lured over, complimented, etc. (“Here, boy! Come!”), following which the woman reported to the police that she was terribly alarmed by the encounter and, while brandishing a restraining order application she’d filled out, had the man charged with stalking. Though the meeting was recorded on store surveillance video and was unremarkable, the woman had no difficulty persuading a male officer that she responded to the man in a friendly manner because she was afraid of him (a single father out with his two little kids). The man also reports (desperately and apologetic for being a “bother”) that he and his children have been baited and threatened on Facebook, including by a female friend of his ex’s and by strangers.

What a broader yet nuanced definition of stalking like Dr. Palmatier’s reveals is that what makes someone a stalker isn’t how his or her target perceives him or her; it’s how s/he perceives his or her target: as an object (what stalking literally means is the stealthy pursuit of prey—that is, food).

What a broader yet nuanced definition of stalking like Dr. Palmatier’s reveals is that what makes someone a stalker isn’t how his or her target perceives him or her; it’s how s/he perceives his or her target: as an object (what stalking literally means is the stealthy pursuit of prey—that is, food). Placed in proper perspective, then, not all acts of stalkers are rejected or alarming, because their targets don’t perceive their motives as deviant or predatory. The overtures of stalkers, interpreted as normal courtship behaviors, may be invited or even welcomed by the unsuspecting.

Placed in proper perspective, then, not all acts of stalkers are rejected or alarming, because their targets don’t perceive their motives as deviant or predatory. The overtures of stalkers, interpreted as normal courtship behaviors, may be invited or even welcomed by the unsuspecting. courts by disordered personalities as stalkers ignite in them the need to clear their names, on which their livelihoods may depend (never mind their sanity); and their determination, which for obvious reasons may be obsessive, seemingly corroborates stalkers’ false allegations of stalking.

courts by disordered personalities as stalkers ignite in them the need to clear their names, on which their livelihoods may depend (never mind their sanity); and their determination, which for obvious reasons may be obsessive, seemingly corroborates stalkers’ false allegations of stalking.

Contemplating these statements should also make clear the all-but-impossible task that counteracting the fraudulent allegations of high-conflict people can pose, both because disordered personalities lie without compunction and because they’re intensely invested in domination, blaming, and punishment.

Contemplating these statements should also make clear the all-but-impossible task that counteracting the fraudulent allegations of high-conflict people can pose, both because disordered personalities lie without compunction and because they’re intensely invested in domination, blaming, and punishment. I’ve read Freud, Lacan, and some other abstruse psychology texts, because I was trained as a literary analyst, and psychological theories are sometimes used by textual critics as interpretive prisms. None of these equipped me, though, to understand the kind of person who would wantonly lie to police officers and judges, enlist others in smear campaigns, and/or otherwise engage in dedicatedly vicious misconduct.

I’ve read Freud, Lacan, and some other abstruse psychology texts, because I was trained as a literary analyst, and psychological theories are sometimes used by textual critics as interpretive prisms. None of these equipped me, though, to understand the kind of person who would wantonly lie to police officers and judges, enlist others in smear campaigns, and/or otherwise engage in dedicatedly vicious misconduct.