Court records are available for public consumption, freely or for a few dollars, besides people’s home addresses, telephone numbers, birth dates and ages, work histories, list of associates and family members, etc. Men and women falsely targeted for blame in drive-thru court procedures may be fined or jailed for airing information about their accusers’ conduct that’s far less sensitive than what anyone with an Internet connection and a credit card can glean in five minutes—which may include decisions against men and women falsely targeted for blame in drive-thru court procedures….

Decisions of the court in public proceedings are public records.

Remarkably, not even judges grasp the significance of the word public. More astonishing than that many judges today don’t know the first thing about the Internet is that no one in government seems to think it’s important that they be instructed.

The conditioned imperative is blame…and the consequences be damned.

Billions of federal tax dollars have been dedicated over the past 20 years to biasing police and judicial responses to accusations of abuse, but not one has been earmarked to show judges how the Internet works and how the public records they generate may be used.

This post will attempt to amend the lapse.

Here are a mere handful of websites that peddle so-called “private” information:

- backgroundalert.com

- beenverified.com

- checkpeople.com

- instantcheckmate.com

- intelius.com

- peoplefinders.com

- spock.com

- switchboard.com

- truthfinder.com

- ussearch.com

- whitepages.com

What follows is a demonstration of how they work.

In the most recent fiction-based prosecution against the author of this post, it was ruled by a superior court judge that I violated the privacy of my accuser by discussing her motives online, and I was unlawfully prohibited from publicly referencing her in future. My judge was Carmine Cornelio, and here is what is returned (at no charge) if I enter his first and last names into SwitchBoard.com:

- his middle initial,

- his approximate age,

- his phone number (a landline provided by Coxcom),

- his home address (and a map showing where his home is located),

- a tab that provides directions to his house,

- a tab that leads to information about his neighbors,

- the names of a couple of “people [he] may know,” and

- an invitation to “View [his] Background & Public Record Information.”

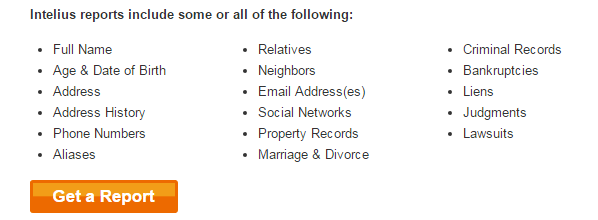

If I enter his name into Intelius.com (again for free), his age is confirmed to be 64, and I’m provided with the names of five of his relatives, as well as his address history, aliases, and prior jobs he’s held (he’s identified as an attorney but not a judge). All of this is right there on the surface. If I cared to know more, here’s what else I could learn for a trivial fee:

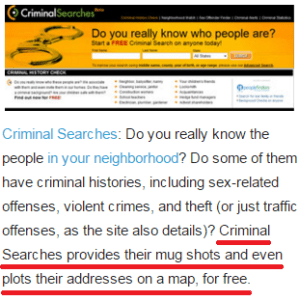

Matthew Chan of Defiantly.net has recently chronicled the case of a New Jersey man, Bruce Aristeo, who was jailed for six months for “vlogging” about a woman who accused him of abuse after he was issued something called an “indefinite temporary restraining order.” The judge didn’t even view the contents of the YouTube videos his ruling was based on. I’ve viewed some of their contents, which are mostly satire and fully protected under the First Amendment, and they’re a lot less invasive that an Intelius report. Mr. Aristeo has been arrested at least four times based on allegations he says are false, and those arrests are all public records that may be pulled from an Intelius report, by an employer, for instance, or a prospective girlfriend.

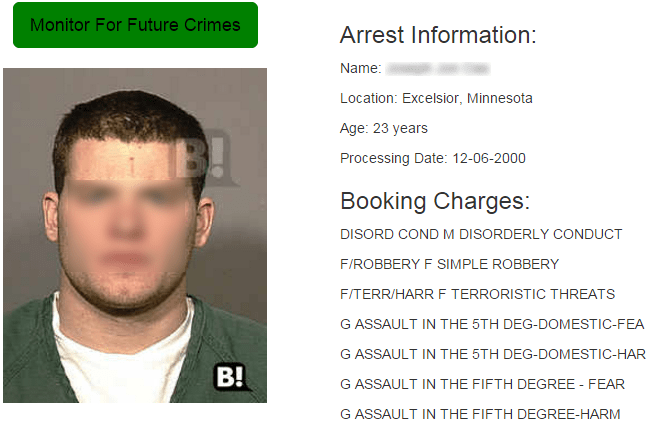

Below is a screenshot from a website called BustedMugshots.com (a product of U.S. Data Co. Ltd.).

I was told by this man’s sister that accusations against him were falsified:

It makes me wonder, how common is this? Because my own brother had his girlfriend and mother of his child accuse him of rape a few years ago. He went to prison for it even though she later recanted her lie, but the case was already in the court’s hands and they wouldn’t accept her testimony. She truly ruined his life.

This certainly isn’t something a viewer of this record (e.g., an employer, a neighbor, or a girlfriend) would conclude. Significantly, also, this record is 15 years old. Court records, besides being very public, are very permanent.

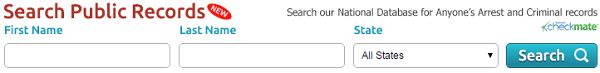

Twice on the same page featuring the above record appears this search bar:

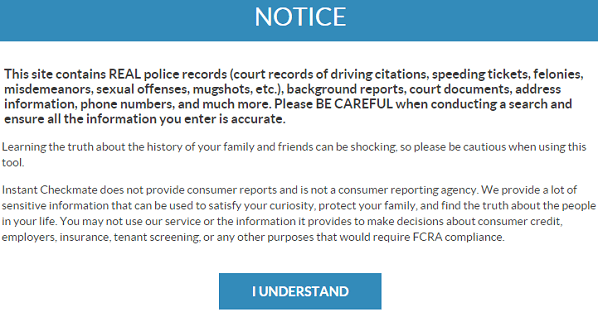

It encourages the viewer to look up the public records of yet other people. A button under the mugshot offers the viewer the option to “Order Complete Background Report” from the same “National Database” (called “Instant Checkmate”). The viewer is also invited to enroll in a service that notifies him or her of future arrests of the same person (“Monitor For Future Crimes”).

People, possibly on arrantly false grounds, are set up as targets for constant and endless scrutiny…to which they can hardly be insensitive.

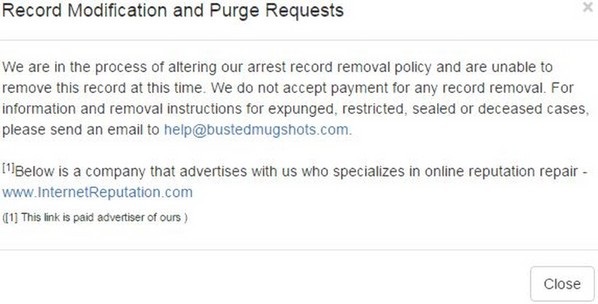

While a line of text under the mugshot suggests a person can “Request This Record to be Modified or Purged,” here’s what pops up when you click its hyperlink:

It’s a tease. The website will only remove the record if it’s been ordered sealed or vacated by the court, or if the person it identifies has died. The blurb hastily clarifies that BustedMugshots.com isn’t out to blackmail people. It doesn’t have to: It collects fees from its advertisers.

Besides advertising the services of Instant Checkmate, BustedMugshots.com advertises for InternetReputation.com, with which the notice above tacitly urges someone with a mugshot published online to inquire (“Protect Your Online Privacy”).

Observe the squeeze: Damning information is published (legally) for the person it concerns to see. That person also sees that anyone can access this and other sensitive information, and is urged to exploit the services of a company that offers to protect his or her reputation…for a fee.

Observe the squeeze: Damning information is published (legally) for the person it concerns to see. That person also sees that anyone can access this and other sensitive information, and is urged to exploit the services of a company that offers to protect his or her reputation…for a fee.

(Summary in media res: A person may be falsely accused in a farcical “trial” and emotionally and financially devastated. S/he may be arrested and imprisoned based on lies. The records may be used to further maim him or her in additional prosecutions. And—and—the records of all of these proceedings, based on a fraud or frauds, may be aired publicly. But the accused may not discuss them defensively without risk of court censure. No wonder, then, that some victims of procedural abuse never want to leave the house and flinch when the doorbell rings.)

This blog concerns restraining orders, which can be obtained easily on hyped or fraudulent grounds and make defendants vulnerable to arrest and conviction for “crimes” that only they can commit, for example, sending an email or placing a phone call.

Vigilant response to any claimed violation of an order has been vigorously conditioned for decades (by the Office on Violence Against Women), and it’s not uncommon for people to report that they’ve been arrested multiple times for falsified violations of restraining orders with falsified bases (see above).

On top of all of this, the records generated by this mischief can be legally published or sold, and the government, besides, has its own public databases that may be freely accessed by anyone with an Internet connection.

These are among the reasons why principle must be restored to process.

Copyright © 2016 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*BustedMugshots.com includes this contemptible sentence in its disclaimer: “The data may not reflect the status of current charges or convictions and all individuals are presumed innocent until proven guilty in a court of law.” Sure they are.

It’s hard to tell whether this is a goad or a guarantee: “Find Restraining Order Records For Anyone Instantly!” Either way, it’s enticing.

It’s hard to tell whether this is a goad or a guarantee: “Find Restraining Order Records For Anyone Instantly!” Either way, it’s enticing. Which appraisal of the significance of restraining orders do you think more closely corresponds to the public’s? (That is a rhetorical question, yes.)

Which appraisal of the significance of restraining orders do you think more closely corresponds to the public’s? (That is a rhetorical question, yes.) Ease of access to restraining order records by the general public differs from state to state. In

Ease of access to restraining order records by the general public differs from state to state. In  One of the aforementioned teachers was on his way to Nashville to become a songwriter, that is, a creative artist. Any career in the public eye like this one is vulnerable to being compromised or trashed by a scandal that may be based on nothing but cunning lies or a disturbed person’s fantasies spewed impulsively in a window of five or 10 minutes. Besides the obvious impairment that something like this can exert on income prospects, its psychological effects alone can make performance of a job impossible. And nothing kills income prospects more surely than that.

One of the aforementioned teachers was on his way to Nashville to become a songwriter, that is, a creative artist. Any career in the public eye like this one is vulnerable to being compromised or trashed by a scandal that may be based on nothing but cunning lies or a disturbed person’s fantasies spewed impulsively in a window of five or 10 minutes. Besides the obvious impairment that something like this can exert on income prospects, its psychological effects alone can make performance of a job impossible. And nothing kills income prospects more surely than that.