Grant Dossetto has a degree in finance he can’t use.

Grant Dossetto has a degree in finance he can’t use.

That’s because a personal protection order (PPO) was petitioned against him in 2010 by a friend, and the law mandates that all restraining order recipients be registered in the FBI’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database—indefinitely.

The Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 requires those working in my field to be fingerprinted and to submit that to the FBI national database. This is on top of normal background checks, disclosure of any and all charitable donations as well as political donations, etc. Ironically we don’t have to pee in a cup for a drug test, but everything else goes well beyond that which my engineering friends et al. have been subjected to. I went to the Livonia police department and had my prints pressed in ink the old fashioned way on the standard card to be delivered to my employer by my first week of employment. The card then was supposed to find its way to the proper regulatory authorities before getting passed through the system.

A month after I began work at the brokerage, I was called by my boss after hours and told to mail back in my key. He fired me while out of town over the phone.

Grant is 27 years old, and he can never realize his ambition to be a stockbroker.

To this day, I have never been sponsored to get my licenses, and I am sure I never will. I can pass the CFA [to become a chartered financial analyst] but cannot take an order for a trade. The PPO destroyed my career.

Though his mother lived to see him earn his degree with honors in 2009, neither of Grant’s parents will ever know that their investment in their son’s success was betrayed or that his professional aspirations were dashed, because they’ve passed away.

Though his mother lived to see him earn his degree with honors in 2009, neither of Grant’s parents will ever know that their investment in their son’s success was betrayed or that his professional aspirations were dashed, because they’ve passed away.

When my father had a heart attack, I was just 14 years old. He passed in his sleep. Before my mom had dragged him off to bed, he had fallen asleep in my room while we were watching TV together and drooled on my pillow. When he didn’t wake the next morning, I can remember opening his mouth to try to resuscitate him and seeing how his tongue was already blackened from lack of oxygen. It was the first time I had to let in an EMT through the wide double front doors to go through the motions to tend to someone who was already gone.

Grant’s mother died in 2010 just days before Grant got word of the court order that identified him as a threat to the safety of a woman he hadn’t even seen in over a year.

I was celebrating a birthday party with my twin brother. He had just been commissioned as an artillery officer in the Marine Corps and was heading to Fort Sill in Oklahoma for training in a couple weeks, so it was a going away party as well. It ended with me carrying my mom up from the bottom of the stairs that led to the basement, blood trickling from the back of her head. She had had a stroke bringing up a food tray and collapsed. The right hemisphere of her brain immediately ceased all activity. I got to stand over another pair of EMTs, this time dabbing her eyes with a tissue. The pupils, fully dilated, failed to show any reaction. She maintained enough brain function to throw up, trying to recover from the worst concussion you could imagine, but by the next day a second opinion came back that she could not survive. My brother and I pulled the plug and held her hand until she forgot to breathe on her own. It took less than a half hour. It was a brilliantly sunny Michigan May day, those days that make suffering through the gray winter worth it. It’s hard to imagine something more at odds with how I felt.

Grant learned a protection order had been issued against him two days later. Notice of it was waiting for him upon his return from the funeral home in the form of a business card a sheriff handed his stepdad.

In Grant’s home state of Michigan, this qualifies as service. No copy of the order was ever provided to him.

In Grant’s home state of Michigan, this qualifies as service. No copy of the order was ever provided to him.

I called the sheriff back, and he went through what I would later come to find out was the front page of the order. He asked me to drive to downtown Detroit, a half hour away, to be served the order. Seeing as I had seven hours of funeral activities in a day and a half, I told him that would be impossible. He said he’d mail it to me. I was never notified that I had just days to appeal or given an explanation of the consequences of the order. The order was never mailed to me. I tried twice to notify the officer that I had not received the PPO. He brushed it off once, and the second call went to voicemail and was never returned.

Grant was denied the opportunity to defend himself in court against an accuser he hadn’t even been in physical proximity to.

The last thing I had said to her was that my mom had died, and I was giving the eulogy at the funeral and would like her there even though we had our differences. The order had been issued ex parte, which requires the court to classify me as an immediate threat who will cause imminent and irreparable damage, per Michigan law. I did not meet those criteria. The hearing was held without my knowledge or participation.

No surprise, Grant has “suffered from severe depression that still surfaces at times now.” His case exemplifies the justice system’s willingness to compound the stresses of real exigencies like family crises with false exigencies like nonexistent danger.

No surprise, Grant has “suffered from severe depression that still surfaces at times now.” His case exemplifies the justice system’s willingness to compound the stresses of real exigencies like family crises with false exigencies like nonexistent danger.

My grandparents were going through their own personal troubles. One had emergency quadruple bypass surgery and is suffering from dementia. One was declared terminal and hung on for two and a half years as his kidneys shut down until he was also unable to tell reality from fiction. One had a hip replacement turn into a seven-surgery odyssey that involved a severe staph infection that ravaged her for most of a year. She needed over 50 blood transfusions over that period and has just recovered from fatigue in the past 12 months. I got a lifetime of bad news I couldn’t control in a couple years, and it took its toll on me.

The order of the court that turned Grant’s career path into a blind alley was petitioned by a woman whose own prospects, Grant says, declined during his senior year of college.

We enjoyed movies, card games (she cheats at euchre), parties, went to school football and hockey games. She sought me out in the parking lot of the campus church and asked me to sit with her at mass. I can’t think of an act of friendship much more intimate than that. When we were close, she was on the dean’s list.

I had been friends with her from September, sophomore year of college until midway through my senior year. In a month, I went from being someone she talked to on Facebook at one in the morning and publically said she loved to being accused of felony property damage—tire-slashing, in particular.

She had gotten involved with a bad crowd, joined a terrible varsity team at school. In April of my junior year, she asked a mutual friend of ours to do cocaine—not exactly something a happy person says. The next fall, I heard about how her parents didn’t give a damn about her, and in November she called my roommate and me over only to snap at us until she kicked us out just before 10 to take a tablespoon of Nyquil that would force her to sleep. She also talked about how she had been getting dizzy and suffering from vertigo, which got her a prescription medication. A doctor had said it was iron deficiency. I can tell you from personal experience it was stress. Her grades slipped to C’s.

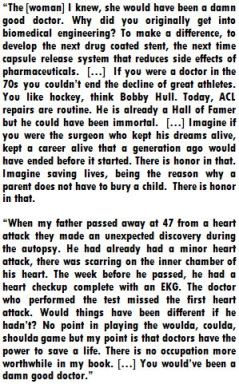

This letter of encouragement represents the “misconduct” of Grant’s that his accuser and the court deemed evidence of “imminent” and potentially “irreparable” harm. The letter ends, “Do what you were meant to do. Be the person you were meant to be.”

As Grant charts his relationship, he urged his friend to make “wholesale changes” and was punished for his concern. “I was sharp,” he says, “but only after I had exhausted every other option.”

Houghton is a small town—population around 10,000—and our school has an undergrad student body of about 6,000. Wal-Mart and not much else is a big deal there as the copper and iron mines shut down decades ago driving out industry and families with it. Not surprisingly, we saw each other a lot the second half of my senior year. I saw her at the gym, had class in an adjacent room two days a week, she worked next door to my lab twice a week, and I worked in the same building as her lab.

I stopped by her house because it was a bad situation given the fact the last thing she had said to me were criminal allegations. We talked for hours, getting along enough that I sincerely believed we had patched things up. She was still miserable, though. One thing got her to brighten up like the girl I first became friends with, and that was a goal to go to med school, a reasonable one for a biomedical engineer.

I invited her out to the movies with my housemates whom she was friends with. I said she should come to the surprise birthday party I was helping to throw for a mutual friend. I tried to get her back to the group she was successful with. For that I got another round of false allegations (destroying the front quarter panel of her car).

When a protection order was issued against Grant in 2010, he hadn’t seen his accuser in over a year. The sheriff who notified him of the order “essentially told [him he] had been contacting her, and now [he] couldn’t.” Grant only got a look at the order that he was never served this month (four years later).

The first time I saw it was two weeks ago. It is a permanent file in the Macomb County Courthouse, file #10-2184-PH. I was marked a threat by my government without me present or ever having physical possession of the order. There is no way for me to have the order removed.

Grant’s former friend, the petitioner of the protection order, had gotten a job after college that apparently hadn’t worked out and returned home. In 2013, the office Grant worked in was slated to relocate near her (in a town of 10,000 residents).

I texted her, because I knew that was a problem. Given what she sent back, I replied that I was going to have to seriously consider leaving my job unless I got assurances from her this wouldn’t be an issue.

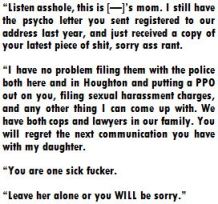

Grant received actual threats from the family of his accuser but says he has never considered applying for a protection order himself.

Grant’s texts instead inspired his accuser to dash to the nearest courthouse all over again.

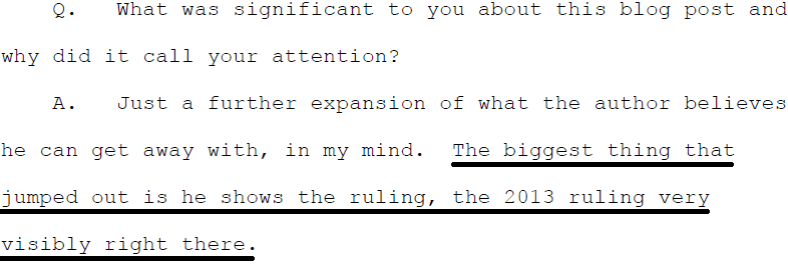

In April 2013, she filed another PPO against me even though I had not seen her in over four years. I had made no attempt to try and meet up with her. It was also issued ex parte, probably because of the first one. She began texting me less than three days after it had taken effect and didn’t show up to the appeals hearing that I scheduled. I missed parts of three days of work to fight an order that she didn’t even feel like defending. In two weeks, the same court, Wayne County this time, ruled against me then for me.

What Grant means is the same court that deemed him a “threat” (sight unseen) was content to consider him benign a couple weeks later just because the protection order petitioner didn’t make a follow-up appearance. His observations underscore the cattle-call nature of restraining order adjudications that readily implicate defendants as criminal menaces but may just as readily conclude they’re harmless and send them home.

Mine was not the only PPO to be overturned—far from it—and the entire docket (about 12 cases) was decided in less than 30 minutes after we waited over an hour for the judge, who was late. Is that justice? How can I ever respect the courts again?

The same orders Grant says were summarily dismissed had just as summarily been approved days or weeks earlier. Restraining orders are typically rubber-stamped upon a few minutes’ “deliberation.”

I sued her after that. In her response to my complaint, she admitted that I had never done anything illegal. You wouldn’t know that by my public record.

Grant dropped the lawsuit, which communicated that he wouldn’t tolerate further prosecutions. The 2010 PPO remains on his record, however, and the stain not only galls him but has derailed his life.

The judge who issued the 2010 order, James Biernat, Sr., is famous for presiding over the “Comic Book Murder” case. It was big enough to make Dateline and the other true crime outlets. He overturned a guilty conviction from a jury and demanded a retrial. The action was extraordinary, held up on appeal by a split decision. The Macomb prosecutor publically rebuked him as being soft on crime. That made national news. All the cable outlets covered the second trial, which yielded the same result: guilty. He was rebuked by two dozen jurors, three appellate justices, and the prosecutor. It’s funny, if he had just given me a hearing, let alone a second, I truly believe a PPO would never have been issued.

The judge who issued the 2010 order, James Biernat, Sr., is famous for presiding over the “Comic Book Murder” case. It was big enough to make Dateline and the other true crime outlets. He overturned a guilty conviction from a jury and demanded a retrial. The action was extraordinary, held up on appeal by a split decision. The Macomb prosecutor publically rebuked him as being soft on crime. That made national news. All the cable outlets covered the second trial, which yielded the same result: guilty. He was rebuked by two dozen jurors, three appellate justices, and the prosecutor. It’s funny, if he had just given me a hearing, let alone a second, I truly believe a PPO would never have been issued.

A questionable judge who is soft on guilty murderers didn’t have a problem destroying a 23-year-old he had never met for non-threatening, legal contact. How could you not believe that the system is hopelessly broken?

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

Since this writing, Grant has channeled his thwarted energies into creative writing and completed a novel, The Hopping Bird, which has been praised in Kirkus Reviews: “Harold Freeman enjoyed success as a player, which included a World Series championship, until it was cut short due to injury. His managerial career has not been as smooth, but that is all behind him as he takes the reins of the Toledo Mud Hens for the 2014 season. After a last place finish in the International League’s West Division a season ago, can he turn the team around?”

Since this writing, Grant has channeled his thwarted energies into creative writing and completed a novel, The Hopping Bird, which has been praised in Kirkus Reviews: “Harold Freeman enjoyed success as a player, which included a World Series championship, until it was cut short due to injury. His managerial career has not been as smooth, but that is all behind him as he takes the reins of the Toledo Mud Hens for the 2014 season. After a last place finish in the International League’s West Division a season ago, can he turn the team around?”

Not one of those things has affected me as deeply as being on the receiving end of a sociopath’s lies, and the legal system’s subsequent validation of those lies. There is no “coming out the other side” of a public, on-the-legal-record character assassination. It gnaws at me on a near-daily basis like one of those worms that lives inside those Mexican jumping beans for sale to tourists on the counters of countless cheesy gift shops in Tijuana.

Not one of those things has affected me as deeply as being on the receiving end of a sociopath’s lies, and the legal system’s subsequent validation of those lies. There is no “coming out the other side” of a public, on-the-legal-record character assassination. It gnaws at me on a near-daily basis like one of those worms that lives inside those Mexican jumping beans for sale to tourists on the counters of countless cheesy gift shops in Tijuana. These days, when sleep escapes me, which seems to be fairly frequently, I often relive the various court hearings associated with this shit show. One is the court hearing for the restraining order that my abuser sought against me (and which was granted) based on his completely vague, bullshit story that he felt “afraid” of me—this from the beast that had assaulted me on numerous occasions, slashed my tires, and had a documented history of abusing previous girlfriends. Another is his trial for assault and battery, during which I was forced to undergo a hostile, nasty, and innuendo-laced cross-examination by his scumbag defense attorney in front of a courtroom full of strangers. But the hearing that really gnaws at me and fills me with an almost homicidal enmity for the judge overseeing it is the one where I was requesting a restraining order against my abuser, this after a particularly heinous assault in the days following my cancer diagnosis and my partial mastectomy.

These days, when sleep escapes me, which seems to be fairly frequently, I often relive the various court hearings associated with this shit show. One is the court hearing for the restraining order that my abuser sought against me (and which was granted) based on his completely vague, bullshit story that he felt “afraid” of me—this from the beast that had assaulted me on numerous occasions, slashed my tires, and had a documented history of abusing previous girlfriends. Another is his trial for assault and battery, during which I was forced to undergo a hostile, nasty, and innuendo-laced cross-examination by his scumbag defense attorney in front of a courtroom full of strangers. But the hearing that really gnaws at me and fills me with an almost homicidal enmity for the judge overseeing it is the one where I was requesting a restraining order against my abuser, this after a particularly heinous assault in the days following my cancer diagnosis and my partial mastectomy. I will have that prick’s bogus restraining order on my record today, tomorrow, next week, and on and on into perpetuity. I am a licensed professional whose employers require a full background check prior to being hired. I honestly don’t know how that restraining order was missed by the company that my most recent employer contracted to perform my pre-employment vetting. I live with the ever-present dread that someday, someone will unearth the perverse landmine that my abusive ex planted in my legal record, and that dread hasn’t lessened one whit since the day the restraining order was granted.

I will have that prick’s bogus restraining order on my record today, tomorrow, next week, and on and on into perpetuity. I am a licensed professional whose employers require a full background check prior to being hired. I honestly don’t know how that restraining order was missed by the company that my most recent employer contracted to perform my pre-employment vetting. I live with the ever-present dread that someday, someone will unearth the perverse landmine that my abusive ex planted in my legal record, and that dread hasn’t lessened one whit since the day the restraining order was granted. I don’t believe this registry will ever be abolished, because restraining order abuse isn’t “sexy” and no one thinks it could ever happen to her, but can we at least limit who can access this information and the circumstances under which they can access it? It’s mind-boggling to me. It’s just so goddamn devastating to the people who are unfairly stigmatized, and, call me pessimistic, but I don’t think these casualties will ever have a voice.

I don’t believe this registry will ever be abolished, because restraining order abuse isn’t “sexy” and no one thinks it could ever happen to her, but can we at least limit who can access this information and the circumstances under which they can access it? It’s mind-boggling to me. It’s just so goddamn devastating to the people who are unfairly stigmatized, and, call me pessimistic, but I don’t think these casualties will ever have a voice.

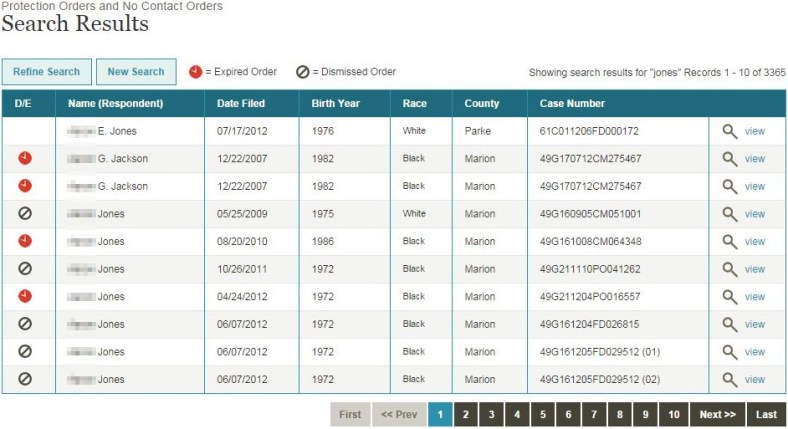

It’s hard to tell whether this is a goad or a guarantee: “Find Restraining Order Records For Anyone Instantly!” Either way, it’s enticing.

It’s hard to tell whether this is a goad or a guarantee: “Find Restraining Order Records For Anyone Instantly!” Either way, it’s enticing. Which appraisal of the significance of restraining orders do you think more closely corresponds to the public’s? (That is a rhetorical question, yes.)

Which appraisal of the significance of restraining orders do you think more closely corresponds to the public’s? (That is a rhetorical question, yes.) Ease of access to restraining order records by the general public differs from state to state. In

Ease of access to restraining order records by the general public differs from state to state. In

People falsely alleged to be abusers on restraining order petitions, particularly men, are treated like brutes, sex offenders, and scum by officers of the court and its staff, besides by authorities and any number of others. Some report their own relatives remain suspicious—often based merely on finger-pointing that’s validated by some judge in a few-minute procedure (and that’s when relatives aren’t the ones making the false allegations).

People falsely alleged to be abusers on restraining order petitions, particularly men, are treated like brutes, sex offenders, and scum by officers of the court and its staff, besides by authorities and any number of others. Some report their own relatives remain suspicious—often based merely on finger-pointing that’s validated by some judge in a few-minute procedure (and that’s when relatives aren’t the ones making the false allegations). So…slanders and libels made by abuse of court process aren’t actionable, slanders and libels that completely sunder the lives of the wrongly accused, who can’t even get them expunged from their records to simply reset their fractured lives to zero.

So…slanders and libels made by abuse of court process aren’t actionable, slanders and libels that completely sunder the lives of the wrongly accused, who can’t even get them expunged from their records to simply reset their fractured lives to zero. One of the thrusts of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) has been to establish public restraining order registries like those that identify sex offenders.

One of the thrusts of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) has been to establish public restraining order registries like those that identify sex offenders.

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

Grant Dossetto has a degree in finance he can’t use.

Grant Dossetto has a degree in finance he can’t use. Though his mother lived to see him earn his degree with honors in 2009, neither of Grant’s parents will ever know that their investment in their son’s success was betrayed or that his professional aspirations were dashed, because they’ve passed away.

Though his mother lived to see him earn his degree with honors in 2009, neither of Grant’s parents will ever know that their investment in their son’s success was betrayed or that his professional aspirations were dashed, because they’ve passed away. In Grant’s home state of Michigan, this qualifies as service. No copy of the order was ever provided to him.

In Grant’s home state of Michigan, this qualifies as service. No copy of the order was ever provided to him. No surprise, Grant has “suffered from severe depression that still surfaces at times now.” His case exemplifies the justice system’s willingness to compound the stresses of real exigencies like family crises with false exigencies like nonexistent danger.

No surprise, Grant has “suffered from severe depression that still surfaces at times now.” His case exemplifies the justice system’s willingness to compound the stresses of real exigencies like family crises with false exigencies like nonexistent danger.

The judge who issued the 2010 order, James Biernat, Sr., is famous for presiding over the “Comic Book Murder” case. It was big enough to make Dateline and the other true crime outlets. He overturned a guilty conviction from a jury and demanded a retrial. The action was extraordinary, held up on appeal by a split decision. The Macomb prosecutor publically rebuked him as being soft on crime. That made national news. All the cable outlets covered the second trial, which yielded the same result: guilty. He was rebuked by two dozen jurors, three appellate justices, and the prosecutor. It’s funny, if he had just given me a hearing, let alone a second, I truly believe a PPO would never have been issued.

The judge who issued the 2010 order, James Biernat, Sr., is famous for presiding over the “Comic Book Murder” case. It was big enough to make Dateline and the other true crime outlets. He overturned a guilty conviction from a jury and demanded a retrial. The action was extraordinary, held up on appeal by a split decision. The Macomb prosecutor publically rebuked him as being soft on crime. That made national news. All the cable outlets covered the second trial, which yielded the same result: guilty. He was rebuked by two dozen jurors, three appellate justices, and the prosecutor. It’s funny, if he had just given me a hearing, let alone a second, I truly believe a PPO would never have been issued.

It’s often reported by recipients of restraining orders that the cops and constables who serve them recognize they’re stigmatizing.

It’s often reported by recipients of restraining orders that the cops and constables who serve them recognize they’re stigmatizing. “Obscure public records” is how some officers of the court think of restraining orders. In the age of the Internet, there are no such things. Many judges are in their 60s and 70s, however, and scarcely know the first thing about the Internet, let alone Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. They’re still living in the days of mimeographs and microfiche.

“Obscure public records” is how some officers of the court think of restraining orders. In the age of the Internet, there are no such things. Many judges are in their 60s and 70s, however, and scarcely know the first thing about the Internet, let alone Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. They’re still living in the days of mimeographs and microfiche.

Defendants’ being railroaded, of course, is nothing extraordinary. “Emergency” restraining orders may allow respondents only a weekend to prepare before having to appear in court to answer allegations—very possibly false allegations—that have the potential to permanently alter the course of their lives.

Defendants’ being railroaded, of course, is nothing extraordinary. “Emergency” restraining orders may allow respondents only a weekend to prepare before having to appear in court to answer allegations—very possibly false allegations—that have the potential to permanently alter the course of their lives.

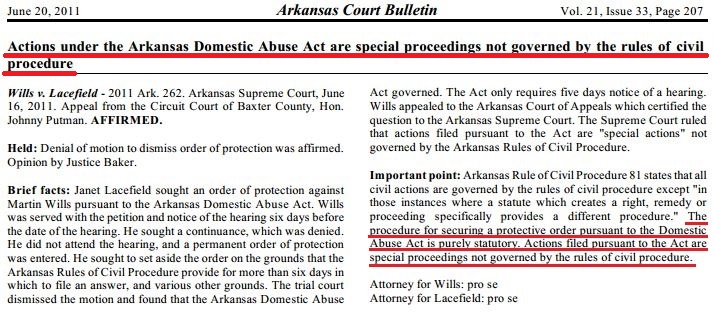

Judge Daniel Sanchez issued a restraining order against Letterman based on those allegations. By doing so, it put Letterman on a national list of domestic abusers, gave him a criminal record, took away several of his constitutionally protected rights, and subjected him to criminal prosecution if he contacted Nestler directly or indirectly, or possessed a firearm.

Judge Daniel Sanchez issued a restraining order against Letterman based on those allegations. By doing so, it put Letterman on a national list of domestic abusers, gave him a criminal record, took away several of his constitutionally protected rights, and subjected him to criminal prosecution if he contacted Nestler directly or indirectly, or possessed a firearm. To some degree at least, this understanding restricts all but the mentally ill, who may be delusional, and

To some degree at least, this understanding restricts all but the mentally ill, who may be delusional, and

I’ll give you a for-instance. Let’s say Person A applies for a protection order and claims Person B threatened to rape her and then kill her with a butcher knife.

I’ll give you a for-instance. Let’s say Person A applies for a protection order and claims Person B threatened to rape her and then kill her with a butcher knife. Person A circulates the details she shared with the court, which are embellished and further honed with repetition, among her friends and colleagues over the ensuing days, months, and years.

Person A circulates the details she shared with the court, which are embellished and further honed with repetition, among her friends and colleagues over the ensuing days, months, and years.

Victims of false allegations made on restraining orders may be labeled “stalker,” “batterer,” “sicko,” “sexual harasser,” “child-abuser,” “whore,” or even “rapist”—publicly and permanently—by accusers whose sole motive is to brutalize. And agents of these victims’ own government(s) arbitrarily authorize this bullying and may baselessly and basely participate in it, compounding the injury exponentially.

Victims of false allegations made on restraining orders may be labeled “stalker,” “batterer,” “sicko,” “sexual harasser,” “child-abuser,” “whore,” or even “rapist”—publicly and permanently—by accusers whose sole motive is to brutalize. And agents of these victims’ own government(s) arbitrarily authorize this bullying and may baselessly and basely participate in it, compounding the injury exponentially.