Since the publication of this post, the “research paper” it responds to has been removed from the Internet.

“I had a false allegation of domestic violence ordered against me on June 19, 2006. It was based on lies, but the local sheriff’s office and state attorney’s office didn’t care that he was a covert, lying narcissist. I doubt they ever heard of the term, in fact. I made the mistake of moving back in with him in September 2008.

“Last year, on July 23, 2013, he, with the help of his conniving sister, literally abandoned me. Left me without transportation and tried to have the electricity cut off. However, the electric company told him it was unlawful to do so. I am disabled, because of him, and have been fighting to get my life, reputation, and sanity restored. It has been over a year, and while life goes on for him, I am still struggling from deep scars of betrayal, lies, and his continued smear campaign against me.

“I thank you for the opportunity to speak out and stand with other true victims of abuse. You see, it isn’t just women who abuse the system, but men, as well.”

—Female e-petition respondent (August 30, 2014)

Contrast this woman’s story with this excerpt from a UC Davis Law Prof. Kelly Behre’s 2014 research paper:

At first glance, the modern fathers’ rights movement and law reform efforts appear progressive, as do the names and rhetoric of the “father’s rights” and “children’s rights” groups advocating for the reforms. They appear a long way removed from the activists who climbed on bridges dressed in superhero costumes or the member martyred by the movement after setting himself on fire on courthouse steps. Their use of civil rights language and appeal to formal gender equality is compelling. But a closer look reveals a social movement increasingly identifying itself as the opposition to the battered women’s movement and intimate partner violence advocates. Beneath a veneer of gender equality language and increased political savviness remains misogynistic undertones and a call to reinforce patriarchy.

The professor’s perceptions aren’t wrong. Her perspective, however, is limited, because stories like the one in the epigraph fall outside of the boundaries of her focus and awareness (and her interest and allegiance, besides).

What isn’t appreciated by critics of various men’s rights advocacy groups is that these groups’ own criticisms are provoked by legal inequities that are inspired and reinforced by feminist groups and their socially networked loyalists. These feminist groups arrogate to themselves the championship of female causes, among them that of battered women. Feminists are the movers behind the “battered women’s movement.”

What isn’t appreciated by critics of various men’s rights advocacy groups is that these groups’ own criticisms are provoked by legal inequities that are inspired and reinforced by feminist groups and their socially networked loyalists. These feminist groups arrogate to themselves the championship of female causes, among them that of battered women. Feminists are the movers behind the “battered women’s movement.”

Those who criticize unfair laws and policies that purport to protect battered women are not “pro-domestic violence”; they’re anti-injustice, which may well mean they’re anti-feminist, and this can be construed as “opposition to the battered women’s movement.” The opposition, however, is to what the feminist movement has wrought. No one is “for” the battery of women or “against” the protection of battered women.

To put this across in a way a feminist can appreciate, to believe women should have the right to abort a fetus is not the same thing as being “pro-abortion.” No one is “for” abortion, and no one is “for” domestic violence. (“Yay, abortion” is never a sign you’ll see brandished by a picketer at a pro-choice demonstration.)

The Daily Beast op-ed this excerpt is drawn from criticizes a group called “Women Against Feminism” and asserts that feminism is defined by the conviction that “men and women should be social, political, and economic equals.” If this were strictly true, then inequities in judicial process that favor female complainants would be a target of feminism’s censure instead of its vigorous support.

The “clash” the professor constructs in her paper is not, strictly speaking, adversarial, and thinking of it this way is the source of the systemic injustices complained of by the groups she targets. Portraying it as a gender conflict is also archly self-serving, because it represents men’s rights groups as “the enemy.” Drawing an Us vs. Them dichotomy (standard practice in the law) promotes a far more visceral opposition to the plaints of men’s groups than the professor’s 64-page evidentiary survey could ever hope to (“Oh, they’re against us, are they?”).

The basic, rational argument against laws intended to curb violence against women is that they privilege women’s interests and deem women more (credit)worthy than men, which has translated to plaintiffs’ being regarded as more “honest” than defendants, and this accounts for female defendants’ also being victimized by false allegations.

(Women, too, are the victims of false restraining orders and fraudulent accusations of domestic abuse. Consequently, women also lose their jobs, their children, their good names, their health, their social credibility, etc.)

The thesis of the professor’s densely annotated paper (“Digging beneath the Equality Language: The Influence of the Father’s Rights Movement on Intimate Partner Violence Public Policy Debates and Family Law Reform”) is that allegations of legal inequities by men’s groups shouldn’t be preferred to facts, and that only facts should exercise influence on decision-making. This assertion is controverted by the professor’s defense of judicial decisions that may be based on no ascertainable facts whatever—and need not be according to the law. The professor on the one hand denounces finger-pointing from men’s groups and on the other hand defends finger-pointing by complainants of abuse, who are predominately women.

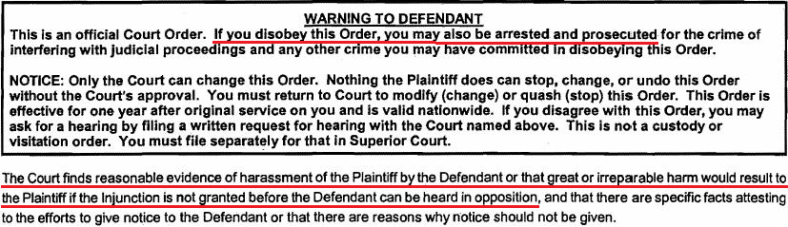

In the arena of law this post concerns, the courts typically follow the dictum that the person pointing the finger is right (and this person is usually female). In other words, the courts judge allegations to be facts. In many instances, what’s more, state law authorizes this formulation. It grants judges the authority “at their discretion” to rule according to accusations and nothing more. Hearsay is fine (and, for example, in California where the professor teaches, the law explicitly says hearsay is fine). The expression of a feeling of danger (genuinely felt or not) suffices as evidence of danger.

The professor’s defense of judicial decision-making based on finger-pointing rather undercuts the credibility of her 64-page polemic against decision-making based on finger-pointing by men’s groups that allege judicial inequities. The professor’s arguments, then, reduce to this position: women’s entitlement to be heeded is greater than men’s.

The problem with critiques of male opposition to domestic violence and restraining order statutes is that those critiques stem from the false presuppositions that (1) the statutes are fair and constitutionally conscientious (they’re not), (2) adjudications based on those statutes are even-handed and just (they’re not), and (3) no one ever exploits those statutes for malicious or otherwise self-serving ends by lying (they do—because they can, for the reasons enumerated above).

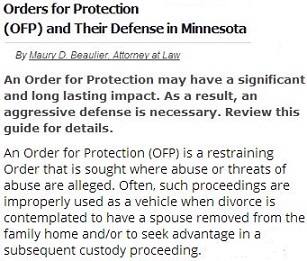

Attorneys acknowledge procedural abuses are common.

Many critiques of men’s, father’s, and children’s rights groups fail to even recognize that motives for lying exist. What presupposition underlies this? That everyone’s an angel? If everyone were an angel, we wouldn’t need laws at all. Or is the presupposition that women are angels? A woman should know better.

A casual Google query will turn up any number of licensed, practicing attorneys all over the country who acknowledge restraining orders and domestic violence laws are abused and offer their services to the falsely accused. Surely the professor wouldn’t allege that these attorneys are fishing for clients who don’t exist—and pretending there’s a problem that doesn’t exist—because they, too, are part of the “anti-battered-women conspiracy.”

The professor’s evidentiary pastiche is at points compelling—it’s only natural that a lot of rage will have been ventilated by people who’ve had their lives torn apart—but her paper’s arguments are finally, exactly like those they criticize, tendentious.

It’s obvious what the professor’s “side” is.

(She accordingly identifies her opposition indiscriminately. For example, the blog you’re right now reading was labeled the product of a father’s rights group or “FRG” in the footnotes of the professor’s paper. This blog is authored by one person only, and he’s not a father. Wronged dads have this writer’s sympathies, but this blog has no affiliation with any groups.)

The professor carefully prefaces her points with phrases like “Researchers have noted,” which gives them the veneer of plausibility but ignores this obvious question: where do the loyalties of those “researchers” lie? The professor cites, for example, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s equation of SAVE Services with a hate group. An attentive survey of SAVE’s reportage, however, would suggest little correspondence. The professor doesn’t quote any of SAVE’s reports; she simply quotes an opposing group’s denunciation of them as being on a par with white supremacist propaganda.

The professor carefully prefaces her points with phrases like “Researchers have noted,” which gives them the veneer of plausibility but ignores this obvious question: where do the loyalties of those “researchers” lie? The professor cites, for example, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s equation of SAVE Services with a hate group. An attentive survey of SAVE’s reportage, however, would suggest little correspondence. The professor doesn’t quote any of SAVE’s reports; she simply quotes an opposing group’s denunciation of them as being on a par with white supremacist propaganda.

(What the professor does quote are some statistics generated by SAVE that she contends are dubious, like estimates of the number and costs of false and frivolous prosecutions. Such estimates must necessarily be speculative, because there are no means of conclusively determining the degree or extent of false allegations. Lies are seldom if ever acknowledged by the courts even if they’re detected. This fact, again, is one that’s corroborated by any number of attorneys who practice in the trenches. Perjury is rarely recognized or punished, so there are no ironclad statistics on its prevalence for advocacy groups to adduce.)

Besides plainly lacking neutrality, insofar as no comparative critical analysis of feminist rhetoric is performed, the professor’s logocentric orientation wants compassion. How much of what she perceives (or at least represents) as bigoted or even crazy would seem all too human if she were to ask herself, for instance, how would I feel if my children were ripped from me by the state in response to lies from someone I trusted, and I were falsely labeled a monster and kicked shoeless to the curb? Were she to ask herself this question and answer it honestly, most of the outraged and inflammatory language she finds offensively “vitriolic” and incendiary would quite suddenly seem understandable, if not sympathetic.

The professor’s approach is instead coolly legalistic, which is exactly the approach that has spawned the heated actions and language she finds objectionable.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

After sitting huddled in a corner and pronouncing, “I want to die,” she rallies and confronts her former lover while he’s conducting a business meeting. Without much prelude, she kicks him in the testicles and bloodies his nose.

After sitting huddled in a corner and pronouncing, “I want to die,” she rallies and confronts her former lover while he’s conducting a business meeting. Without much prelude, she kicks him in the testicles and bloodies his nose. Had the man surreptitiously shot the photos and aired them without her consent, she could have taken him to the cleaners. The courts do more than frown upon that kind of thing, especially when the photos are nudies.

Had the man surreptitiously shot the photos and aired them without her consent, she could have taken him to the cleaners. The courts do more than frown upon that kind of thing, especially when the photos are nudies. The account below, by Rosemary Anderson of Australia, was submitted to the e-petition End Restraining Order Abuses (since terminated by its host) and is highlighted here to show (1) that restraining orders are abused not only by intimates but by neighbors and strangers, (2) that the ease with which they’re applied for entices vexatious litigants (especially once their appetite has been whetted), and (3) that restraining orders are abused in countries other than the United States.

The account below, by Rosemary Anderson of Australia, was submitted to the e-petition End Restraining Order Abuses (since terminated by its host) and is highlighted here to show (1) that restraining orders are abused not only by intimates but by neighbors and strangers, (2) that the ease with which they’re applied for entices vexatious litigants (especially once their appetite has been whetted), and (3) that restraining orders are abused in countries other than the United States. The matter began when we opposed the expansion of their egg farm. We did so through the appropriate channels and in the appropriate manner. They have a CCW on their property and for reasons unknown were allowed to build the egg farm far too close to our boundary and house.

The matter began when we opposed the expansion of their egg farm. We did so through the appropriate channels and in the appropriate manner. They have a CCW on their property and for reasons unknown were allowed to build the egg farm far too close to our boundary and house. She once threatened my employer to get me sacked. I had luckily recorded several previous incidents that proved to my boss the lies they tell. They once took us to court over the boundary fence even though we had evidence in the form of letters and photos. Miraculously they won as they brought the non-professional fencing person with them as a witness. We weren’t given the appropriate notice by the court of their witness and could have selected several witnesses of our own to prove the fencing contractor assisted our neighbours to make a false insurance claim. The summons for this also came 18 months after we had given them what we had considered an appropriate payment. They had cashed the cheque and never contacted us in between to dispute it.

She once threatened my employer to get me sacked. I had luckily recorded several previous incidents that proved to my boss the lies they tell. They once took us to court over the boundary fence even though we had evidence in the form of letters and photos. Miraculously they won as they brought the non-professional fencing person with them as a witness. We weren’t given the appropriate notice by the court of their witness and could have selected several witnesses of our own to prove the fencing contractor assisted our neighbours to make a false insurance claim. The summons for this also came 18 months after we had given them what we had considered an appropriate payment. They had cashed the cheque and never contacted us in between to dispute it. J, a single dad who lives in Texas with his two kids, submitted his story as a comment to the blog in September, prefacing it: “I am writing this to share [it] with the rest of my fellow male victims [who] fall in with the dreaded Crazy.”

J, a single dad who lives in Texas with his two kids, submitted his story as a comment to the blog in September, prefacing it: “I am writing this to share [it] with the rest of my fellow male victims [who] fall in with the dreaded Crazy.” Because it was all complete bullsh*t.

Because it was all complete bullsh*t. He gave me the number of an attorney friend who worked in Little Rock. Next thing I knew, I’m having to fax or email every record I kept that shows my whereabouts on that day: gas receipts, store receipts, etc. I had to get a list of movies that I watched from the video download company we use. Cell phone calls. Text messages. (By the way, they really do monitor those. They can pinpoint your exact location, but you have to send a written request.) All of this to prove I was not there. Once I gave that attorney everything, he told me he would go to court that day and ask for an extension of 60 days. And I would still have to show up in Arkansas. Sh*t!

He gave me the number of an attorney friend who worked in Little Rock. Next thing I knew, I’m having to fax or email every record I kept that shows my whereabouts on that day: gas receipts, store receipts, etc. I had to get a list of movies that I watched from the video download company we use. Cell phone calls. Text messages. (By the way, they really do monitor those. They can pinpoint your exact location, but you have to send a written request.) All of this to prove I was not there. Once I gave that attorney everything, he told me he would go to court that day and ask for an extension of 60 days. And I would still have to show up in Arkansas. Sh*t! The day of the court hearing came. I drove out of state to be there. She actually showed in up in court that day. I suspect she didn’t expect I would show. The judge called out our docket. She sat on one side of the courtroom. My attorney and I sat on the other.

The day of the court hearing came. I drove out of state to be there. She actually showed in up in court that day. I suspect she didn’t expect I would show. The judge called out our docket. She sat on one side of the courtroom. My attorney and I sat on the other. Journalists who recognize the harm of facile or false allegations invariably focus on

Journalists who recognize the harm of facile or false allegations invariably focus on  The implications of restraining orders, what’s more, are generic. There’s no specific charge associated with them. They’re catchalls that categorically imply everything sordid, violent, and creepy. They most urgently suggest stalking, violence, and sexual deviance.

The implications of restraining orders, what’s more, are generic. There’s no specific charge associated with them. They’re catchalls that categorically imply everything sordid, violent, and creepy. They most urgently suggest stalking, violence, and sexual deviance.

I bonded with a client recently while wrestling a tough job to conclusion. I’ll call him “Joe.” Joe and I were talking in his backyard, and he confided to me that his next-door neighbor was “crazy.” She’d reported him to the police “about a 100 times,” he said, including for listening to music after dark on his porch.

I bonded with a client recently while wrestling a tough job to conclusion. I’ll call him “Joe.” Joe and I were talking in his backyard, and he confided to me that his next-door neighbor was “crazy.” She’d reported him to the police “about a 100 times,” he said, including for listening to music after dark on his porch.

It gets by with a little help from its friends.

It gets by with a little help from its friends. Prof. Meier says she expects to use the $500,000 federal grant to conclusively expose gender bias in family court against women—and to do it using a study sample of “over 1,000 court cases from the past 15 years” (a study sample, in other words, of fewer than 2,000 cases).

Prof. Meier says she expects to use the $500,000 federal grant to conclusively expose gender bias in family court against women—and to do it using a study sample of “over 1,000 court cases from the past 15 years” (a study sample, in other words, of fewer than 2,000 cases).

Some recent posts on this blog have touched on what might be called the five magic words, because their utterance may be all that’s required of a petitioner to obtain a restraining order. The five magic words are these: “I’m afraid for my life.”

Some recent posts on this blog have touched on what might be called the five magic words, because their utterance may be all that’s required of a petitioner to obtain a restraining order. The five magic words are these: “I’m afraid for my life.” Gamesmanship in this arena is both bottom-up and top-down. Liars hustle judges…and judges hustle liars along.

Gamesmanship in this arena is both bottom-up and top-down. Liars hustle judges…and judges hustle liars along.

A presumption of people—including even

A presumption of people—including even  People on the outside of the restraining order process imagine that the phrase false accusations refers to elaborately contrived frame-ups. Frame-ups certainly occur, but they’re mostly improvised. We’re talking about processes that are mere minutes in duration (that includes the follow-up hearings that purport to give defendants the chance to refute the allegations against them).

People on the outside of the restraining order process imagine that the phrase false accusations refers to elaborately contrived frame-ups. Frame-ups certainly occur, but they’re mostly improvised. We’re talking about processes that are mere minutes in duration (that includes the follow-up hearings that purport to give defendants the chance to refute the allegations against them). Judge Stump quickly signed the order, and the judge and mamma hustled Linda into a hospital, telling her it was for an appendicitis operation. Linda was then sterilized without her knowledge. Two years later, Linda married a Leo Sparkman and discovered that she had been sterilized without her knowledge. The Sparkmans proceeded to sue mamma, mamma’s attorney, the doctors, the hospital, and Judge Stump, alleging a half-dozen constitutional violations.

Judge Stump quickly signed the order, and the judge and mamma hustled Linda into a hospital, telling her it was for an appendicitis operation. Linda was then sterilized without her knowledge. Two years later, Linda married a Leo Sparkman and discovered that she had been sterilized without her knowledge. The Sparkmans proceeded to sue mamma, mamma’s attorney, the doctors, the hospital, and Judge Stump, alleging a half-dozen constitutional violations.

My son’s girlfriend…filed a domestic abuse CPO [civil protection order] against my son, again telling him that he shouldn’t have left her. He hasn’t been served yet—they keep missing him. She calls my son constantly, stringing him along with the idea that she “might” let it go. He’s taking her out to eat, giving her money, staying the night with her. Hoping that she’ll let it go. All that and yet two hearing dates for him have come and gone with her showing up at both his hearings asking for a continuance because he hasn’t been served.

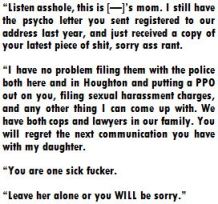

My son’s girlfriend…filed a domestic abuse CPO [civil protection order] against my son, again telling him that he shouldn’t have left her. He hasn’t been served yet—they keep missing him. She calls my son constantly, stringing him along with the idea that she “might” let it go. He’s taking her out to eat, giving her money, staying the night with her. Hoping that she’ll let it go. All that and yet two hearing dates for him have come and gone with her showing up at both his hearings asking for a continuance because he hasn’t been served. That includes control of the truth. Some cases of blackmail this author has been informed of were instances of the parties accused knowing something about their accusers that their accusers didn’t want to get around (usually criminal activity). When the guilty parties no longer trusted that coercion would ensure that those who had the goods on them would keep quiet, they filed restraining orders against them alleging abuse, which instantly discredited anything the people they accused might disclose about their activities.

That includes control of the truth. Some cases of blackmail this author has been informed of were instances of the parties accused knowing something about their accusers that their accusers didn’t want to get around (usually criminal activity). When the guilty parties no longer trusted that coercion would ensure that those who had the goods on them would keep quiet, they filed restraining orders against them alleging abuse, which instantly discredited anything the people they accused might disclose about their activities. A recent NPR story reports that dozens of students who’ve been accused of rape are suing their universities. They allege they were denied due process and fair treatment by college investigative committees, that is, that they were “railroaded” (and publicly humiliated and reviled). The basis for a suit alleging civil rights violations, then, might also exist (that is, independent of claims of material privation). Certainly most or all restraining order defendants and many domestic violence defendants are “railroaded” and subjected to public shaming and social rejection unjustly.

A recent NPR story reports that dozens of students who’ve been accused of rape are suing their universities. They allege they were denied due process and fair treatment by college investigative committees, that is, that they were “railroaded” (and publicly humiliated and reviled). The basis for a suit alleging civil rights violations, then, might also exist (that is, independent of claims of material privation). Certainly most or all restraining order defendants and many domestic violence defendants are “railroaded” and subjected to public shaming and social rejection unjustly. Undertaking a venture like coordinating a class action is beyond the resources of this writer, but anyone with the gumption to try and transform words into action is welcome to post a notice here.

Undertaking a venture like coordinating a class action is beyond the resources of this writer, but anyone with the gumption to try and transform words into action is welcome to post a notice here.

The scales of justice are tipped from the start.

The scales of justice are tipped from the start. The savvy observer will note that suspicion is the motive determiner of liability at all levels. Suspicion informs judicial disposition, subsequent police response to claims of violation, and of course interpretation by third parties, including employers (judges trust accusers, and everyone else trusts judges). Emphatically worthy of remark is that

The savvy observer will note that suspicion is the motive determiner of liability at all levels. Suspicion informs judicial disposition, subsequent police response to claims of violation, and of course interpretation by third parties, including employers (judges trust accusers, and everyone else trusts judges). Emphatically worthy of remark is that  From these concepts, questions immediately present themselves. Are protection orders being utilized in oppressive or unexpected ways? Are the factual scenarios involved similar to what the [legislature] envisioned them to be? Are courts utilizing protection order tools correctly? Are judges issuing ex parte orders that trample upon the rights of innocent people before a hearing is held to determine the validity of specific allegations? Is this area of the law an insufficiently regulated “wild frontier”?

From these concepts, questions immediately present themselves. Are protection orders being utilized in oppressive or unexpected ways? Are the factual scenarios involved similar to what the [legislature] envisioned them to be? Are courts utilizing protection order tools correctly? Are judges issuing ex parte orders that trample upon the rights of innocent people before a hearing is held to determine the validity of specific allegations? Is this area of the law an insufficiently regulated “wild frontier”? While how commonly the process is exploited for ulterior motives is a matter of heated dispute, its availability for abuse is plain. The

While how commonly the process is exploited for ulterior motives is a matter of heated dispute, its availability for abuse is plain. The

The news story the epigraph was excerpted from was prompted by a recent murder in Oregon and explores the impotence of restraining orders, in particular to “stop bullets.” Just as shooting sprees inspire reporters to investigate gun legislation, murder victims who had applied for restraining orders that proved worthless inspire reporters to investigate restraining order policies. The presumption, always, is that the law failed.

The news story the epigraph was excerpted from was prompted by a recent murder in Oregon and explores the impotence of restraining orders, in particular to “stop bullets.” Just as shooting sprees inspire reporters to investigate gun legislation, murder victims who had applied for restraining orders that proved worthless inspire reporters to investigate restraining order policies. The presumption, always, is that the law failed.

“For some people it’s more dangerous [to get a restraining order],” said Kim Larson, director for Marion County District Attorney Victim Assistance Division. “Sometimes it makes people really angry, getting served with a restraining order.”

“For some people it’s more dangerous [to get a restraining order],” said Kim Larson, director for Marion County District Attorney Victim Assistance Division. “Sometimes it makes people really angry, getting served with a restraining order.” My ex-husband’s family just filed their second bogus restraining order against me to overturn custody of our 13-year-old. The first one, three years ago, I spent three months and $25,000 to fight, and got my son back. This one? I promised myself not to fight if they tried again, and I didn’t and lost today in court. They upheld the emergency order of protection and extended a restraining order against me for no contact with my own son for nothing I did at all—for two years. My son wants to be with them, so I’m not fighting. I just don’t want him to grow up thinking I did anything wrong and that’s why they took him from me. I don’t need to lose any more money and get fired from any more jobs trying to fight…. I’m done.

My ex-husband’s family just filed their second bogus restraining order against me to overturn custody of our 13-year-old. The first one, three years ago, I spent three months and $25,000 to fight, and got my son back. This one? I promised myself not to fight if they tried again, and I didn’t and lost today in court. They upheld the emergency order of protection and extended a restraining order against me for no contact with my own son for nothing I did at all—for two years. My son wants to be with them, so I’m not fighting. I just don’t want him to grow up thinking I did anything wrong and that’s why they took him from me. I don’t need to lose any more money and get fired from any more jobs trying to fight…. I’m done. Feminists are encouraged to respond to this mom’s story, whether with sympathy or criticism. The court process she’s a victim of isn’t one this writer condones. Let’s hear from some people who do condone it.

Feminists are encouraged to respond to this mom’s story, whether with sympathy or criticism. The court process she’s a victim of isn’t one this writer condones. Let’s hear from some people who do condone it.

On 15 March 2009 at 11.07pm: Hi there! How are you? I am lying in my bed and thinking…I miss you and miss having you in my life and I would love to have you back in it…. I do have a lot of issues, I know, and I suppose I am a difficult woman at times…. In the same breath, I could have made the biggest tit out of myself now, because you might have met someone else…. Deep down inside I hope you miss me as much as I miss you! […] I don’t want you to feel that I am pressurising you….

On 15 March 2009 at 11.07pm: Hi there! How are you? I am lying in my bed and thinking…I miss you and miss having you in my life and I would love to have you back in it…. I do have a lot of issues, I know, and I suppose I am a difficult woman at times…. In the same breath, I could have made the biggest tit out of myself now, because you might have met someone else…. Deep down inside I hope you miss me as much as I miss you! […] I don’t want you to feel that I am pressurising you…. A female respondent to the blog brought my attention to the three-year-old story out of Cape Town, South Africa from which the epigraph is excerpted. It’s about a man who was served with a domestic violence restraining order (later revised to a stalking protection order) petitioned by a woman he’d threatened to “un-friend” on Facebook and with whom he’d never had a domestic relationship (he says they had fatefully “kissed once or twice” during a “brief fling”). The order was apparently the tag-team brainchild of this woman, who would be called a stalker according to even the most forgiving standards, and another woman, an attorney the man had dated for six months.

A female respondent to the blog brought my attention to the three-year-old story out of Cape Town, South Africa from which the epigraph is excerpted. It’s about a man who was served with a domestic violence restraining order (later revised to a stalking protection order) petitioned by a woman he’d threatened to “un-friend” on Facebook and with whom he’d never had a domestic relationship (he says they had fatefully “kissed once or twice” during a “brief fling”). The order was apparently the tag-team brainchild of this woman, who would be called a stalker according to even the most forgiving standards, and another woman, an attorney the man had dated for six months.

Here are two recent headlines that caught my eye: “

Here are two recent headlines that caught my eye: “ Recognize that in these rare instances when perjury statutes are enforced, the motive is political impression management (government face-saving). Everyday claimants who lie to judges are never charged at all, because the victims of their lies (moms, dads,

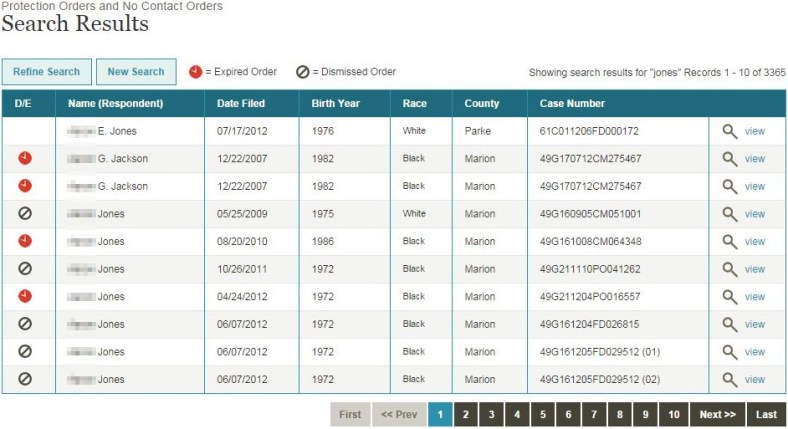

Recognize that in these rare instances when perjury statutes are enforced, the motive is political impression management (government face-saving). Everyday claimants who lie to judges are never charged at all, because the victims of their lies (moms, dads,  One of the thrusts of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) has been to establish public restraining order registries like those that identify sex offenders.

One of the thrusts of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) has been to establish public restraining order registries like those that identify sex offenders.

pay them money I didn’t even owe! This person was my babysitter, who is the most manipulative, money hungry witch. I just didn’t know it until now.

pay them money I didn’t even owe! This person was my babysitter, who is the most manipulative, money hungry witch. I just didn’t know it until now.

Appreciate that the court’s basis for issuing the document capped with the “Warning” pictured above is nothing more than some allegations from the order’s plaintiff, allegations scrawled on a form and typically made orally to a judge in four or five minutes.

Appreciate that the court’s basis for issuing the document capped with the “Warning” pictured above is nothing more than some allegations from the order’s plaintiff, allegations scrawled on a form and typically made orally to a judge in four or five minutes.

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

What isn’t appreciated by critics of various men’s rights advocacy groups is that these groups’ own criticisms are provoked by legal inequities that are inspired and reinforced by feminist groups and their socially networked loyalists. These feminist groups arrogate to themselves the championship of female causes, among them that of battered women. Feminists are the movers behind the “battered women’s movement.”

What isn’t appreciated by critics of various men’s rights advocacy groups is that these groups’ own criticisms are provoked by legal inequities that are inspired and reinforced by feminist groups and their socially networked loyalists. These feminist groups arrogate to themselves the championship of female causes, among them that of battered women. Feminists are the movers behind the “battered women’s movement.”

The professor carefully prefaces her points with phrases like “Researchers have noted,” which gives them the veneer of plausibility but ignores this obvious question: where do the loyalties of those “researchers” lie? The professor cites, for example, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s equation of SAVE Services with a hate group. An attentive survey of SAVE’s reportage, however, would suggest little correspondence. The professor doesn’t quote any of SAVE’s reports; she simply quotes an opposing group’s denunciation of them as being on a par with white supremacist propaganda.

The professor carefully prefaces her points with phrases like “Researchers have noted,” which gives them the veneer of plausibility but ignores this obvious question: where do the loyalties of those “researchers” lie? The professor cites, for example, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s equation of SAVE Services with a hate group. An attentive survey of SAVE’s reportage, however, would suggest little correspondence. The professor doesn’t quote any of SAVE’s reports; she simply quotes an opposing group’s denunciation of them as being on a par with white supremacist propaganda.

Grant Dossetto has a degree in finance he can’t use.

Grant Dossetto has a degree in finance he can’t use. Though his mother lived to see him earn his degree with honors in 2009, neither of Grant’s parents will ever know that their investment in their son’s success was betrayed or that his professional aspirations were dashed, because they’ve passed away.

Though his mother lived to see him earn his degree with honors in 2009, neither of Grant’s parents will ever know that their investment in their son’s success was betrayed or that his professional aspirations were dashed, because they’ve passed away. In Grant’s home state of Michigan, this qualifies as service. No copy of the order was ever provided to him.

In Grant’s home state of Michigan, this qualifies as service. No copy of the order was ever provided to him. No surprise, Grant has “suffered from severe depression that still surfaces at times now.” His case exemplifies the justice system’s willingness to compound the stresses of real exigencies like family crises with false exigencies like nonexistent danger.

No surprise, Grant has “suffered from severe depression that still surfaces at times now.” His case exemplifies the justice system’s willingness to compound the stresses of real exigencies like family crises with false exigencies like nonexistent danger.

The judge who issued the 2010 order, James Biernat, Sr., is famous for presiding over the “Comic Book Murder” case. It was big enough to make Dateline and the other true crime outlets. He overturned a guilty conviction from a jury and demanded a retrial. The action was extraordinary, held up on appeal by a split decision. The Macomb prosecutor publically rebuked him as being soft on crime. That made national news. All the cable outlets covered the second trial, which yielded the same result: guilty. He was rebuked by two dozen jurors, three appellate justices, and the prosecutor. It’s funny, if he had just given me a hearing, let alone a second, I truly believe a PPO would never have been issued.

The judge who issued the 2010 order, James Biernat, Sr., is famous for presiding over the “Comic Book Murder” case. It was big enough to make Dateline and the other true crime outlets. He overturned a guilty conviction from a jury and demanded a retrial. The action was extraordinary, held up on appeal by a split decision. The Macomb prosecutor publically rebuked him as being soft on crime. That made national news. All the cable outlets covered the second trial, which yielded the same result: guilty. He was rebuked by two dozen jurors, three appellate justices, and the prosecutor. It’s funny, if he had just given me a hearing, let alone a second, I truly believe a PPO would never have been issued.

Members of the legislative subcommittee referenced in The Courant article reportedly expect to improve their understanding of the flaws inherent in the restraining order process by taking a field trip. They plan “a ‘ride along’ with the representative of the state marshals on the panel…to learn more about how restraining orders are served.”

Members of the legislative subcommittee referenced in The Courant article reportedly expect to improve their understanding of the flaws inherent in the restraining order process by taking a field trip. They plan “a ‘ride along’ with the representative of the state marshals on the panel…to learn more about how restraining orders are served.”