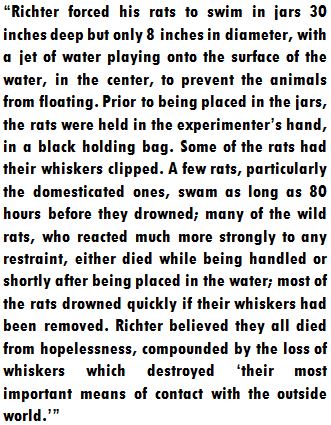

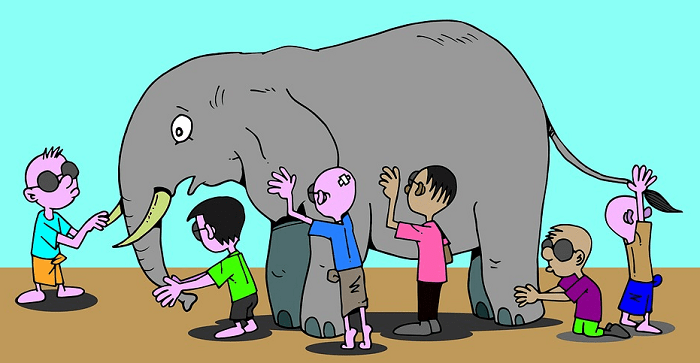

“Learned helplessness is behavior typical of an organism (human or animal) that has endured repeated painful or otherwise aversive stimuli which it was unable to escape or avoid. After such experience, the organism often fails to learn escape or avoidance in new situations where such behavior would be effective. In other words, the organism seems to have learned that it is helpless in aversive situations, that it has lost control, and so it gives up trying. Such an organism is said to have acquired learned helplessness. Learned helplessness theory is the view that clinical depression and related mental illnesses may result from such real or perceived absence of control over the outcome of a situation.”

—Wikipedia

I introduced this psychological theory to a judge in 2010 when I filed a lawsuit against a woman who falsely accused me to the police and multiple courts in 2006. The accusations began in March, and before the close of July, she had defrauded at least four judges.

To be falsely accused is bewildering; it savages the mind. To then learn that efforts to expose the truth are met by judges not with keen interest and probing questions but variably with mute indifference, scornful derision, and offhand dismissal—that’s to have it firmly impressed upon you that resistance is futile. Worse, it’s to learn that resistance compounds the frustration and pain.

The system isn’t on your side, and bucking it for many is just an invitation to be scourged afresh.

After attempting some direct appeals to people who, I reasoned, might care more about the truth than the court did (2007), then writing about the business online (2008), then employing an attorney to mediate a resolution (2009), all of which efforts were met with stony silence, I filed a lawsuit (on my own).

That was in 2010. By then, unknown to me, the statutes of limitation on the civil torts I alleged—fraud, false light, defamation, and intentional infliction of emotional distress—had flown. My accuser’s attorney, with mock ingenuousness, wondered to the court why I hadn’t filed my suit in 2006, right after having had the court twice swat down my appeals.

I offered the explanation to the judge that people who go through this become conditioned to helplessness (or hopelessness), because process militates against the proposition that a claimant of abuse has engaged in deception. The righteous indignation and outrage of the wronged defendant gradually succumb to the inevitable conclusion that facts, truth, and reason are impotent against fraud and judicial bias. (The defendant lives besides under the constant menace of unwarranted arrest.)

I offered the explanation to the judge that people who go through this become conditioned to helplessness (or hopelessness), because process militates against the proposition that a claimant of abuse has engaged in deception. The righteous indignation and outrage of the wronged defendant gradually succumb to the inevitable conclusion that facts, truth, and reason are impotent against fraud and judicial bias. (The defendant lives besides under the constant menace of unwarranted arrest.)

I didn’t know I could prosecute a lawsuit on my own until a legal assistant told me so in 2009, which I also told the judge. I might have been motivated to find out sooner if I’d had the least faith that a judge would heed my testimony.

My accuser’s attorney disdained the explanation for my tardy filing as “self-diagnosis,” and the judge eagerly echoed his assessment and dismissed the case (the court’s interest is in economy, not truth or justice). What was another six months of my life? (Letters from a physician and a therapist, along with witness affidavits, including one from a former cop, made no difference.)

I wasn’t wrong, though. People who defy a rigged system—whether restraining order defendants, domestic violence defendants, or family court defendants—can be conditioned to helplessness, and many accordingly report experiencing posttraumatic stress (which fortifies their distrust and their aversion to further rude scrutiny and contemptuous treatment from the court).

A lesson to take from this is that the “high road” (i.e., trusting in facts, truth, and reason) is a detour to hell. If I had known in 2006 what I know today, I could have extricated myself from my accuser’s false accusations in five minutes by playing the game according to her rules, which were “whatever works.”

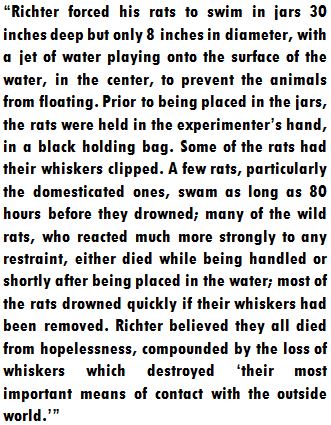

The studies from which the term “learned helplessness” emerged were studies of drowned rats and tortured dogs. Playing fair (or aspiring to saintliness by never uttering an ill word against your accuser) is noble, but nobly drowned is still drowned. If an accuser lies about you, denounce him or her as a liar. Similarly, if a process of law is bullshit, call it what it is.

Some respondents to this blog, even after they’ve been through the courthouse ringer, retain a beleaguered faith in ethics. They believe that if injustice is laid bare to a discerning audience by rhetorical appeals to reason and decency, this will spur change. “Our objective is to fix the problem, not the blame” was quoted in a recent comment.

The abstract and impersonal may be informative, but they don’t arouse curiosity, because they don’t inflame the passions; controversy does. Advocates of the “high road” eschew naming names, for example, because it’s aggressive. Avoidance of confrontation, however, accomplishes little and exemplifies “learned helplessness.” The “high road” is safe and tame, and it leads to a dead-end.

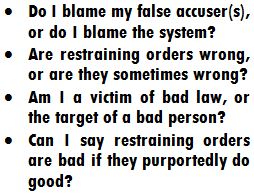

The reason restraining order abuse endures is that the abused are paralyzed by indecisiveness. They won’t knuckle down and demand that a flawed process be repealed.

Among people who’ve been damaged by fraudulent abuse of restraining orders and related civil court procedures that are supposed to protect the defenseless, you’ve got, for instance, your liberals who’ll defend the process on principle, because they insist it must be preserved to protect the vulnerable, and they’ll fence-sit just to spite conservatives who flatly denounce the process as a governmental intrusion that undermines family.

Among people who’ve been damaged by fraudulent abuse of restraining orders and related civil court procedures that are supposed to protect the defenseless, you’ve got, for instance, your liberals who’ll defend the process on principle, because they insist it must be preserved to protect the vulnerable, and they’ll fence-sit just to spite conservatives who flatly denounce the process as a governmental intrusion that undermines family.

Liberals and women who identify with legitimately victimized women feel obligated to “negotiate the gray space” and acknowledge the pros and cons of “women’s law.”

Then you have people (of whatever political allegiance or none) who believe that if you eliminated procedural inequities and ensured that defendants’ due process rights were observed, the system would work fine.

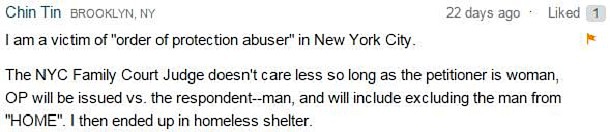

Maybe they believe a process that allows a person in Nevada to mosey into a courthouse, fill out some forms, and accuse a person in Wyoming of “stalking” or “domestic violence,” necessitating that the person in Wyoming hustle him- or herself to Nevada to present a defense within the week, can be made fair, and maybe they don’t know that the same Nevadan can prosecute the same claim over and over against the same Wyomingite (three times, six times, a dozen times, or more).

Maybe they believe that appeals to public conscience will urge the passage of laws that require free legal counsel be provided to defendants.

This would mean that if, say, a million restraining orders are petitioned a year, and legal representation for each defendant in each case could be capped at $2,000 (which might translate to a feeble defense, anyway), state governments would be required to shell out $2,000,000,000 to make everything “fair and square.” But that’s not all. If government gave free representation to “abusers,” advocates for “victims” would demand the same for them. So your $2,000,000,000 would become $4,000,000,000.

That’s per annum. (Also, the hypothetical Wyomingite would still need to travel to Nevada, and who’s paying for that?)

Others believe that if lying (perjury) were prosecuted, that would straighten things out. The costs to prosecute what may be hundreds of thousands of liars a year might be less than $4,000,000,000…or it might not be. Too, how do you prove someone is lying about an emotional state, like “fear”? How do you prove an alleged event didn’t happen?

You can’t, not conclusively, which is what a criminal prosecution requires.

More say appeal to your senator, to the president, to the press…nicely and cogently. They follow a utopian faith that basic decency will prevail if “the problem” is exposed.

As a rhetorical stance, the position has its merits. It suggests calmness and rationality, and calmness and rationality should recommend attention from others. “We’re calm and rational,” proponents of the position imply, “so when we say there’s a problem in need of fixing, it’s calmness and rationality speaking, not anger.”

The limitation is that no one who needs to be convinced has a motive to listen. No one can be made to care about abstractions like equity and due process when in the other ear they’re being cited statistics about epidemic violence.

Everything to do with the law is adversarial. If you seek to revise it without being personal or confrontational, the soonest you can expect a just reward is in the afterlife.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*Splendid writers, particularly Cathy Young, have responsibly and lucidly exposed “the problem” for 20 years in major news outlets. The system has responded with statutes that are broader, laxer, and more punishing.

Among people who’ve been damaged by fraudulent abuse of restraining orders and related civil court procedures that are supposed to protect the defenseless, you’ve got, for instance, your liberals who’ll defend the process on principle, because they insist it must be preserved to protect the vulnerable, and they’ll fence-sit just to spite conservatives who flatly denounce the process as a governmental intrusion that undermines family.

Among people who’ve been damaged by fraudulent abuse of restraining orders and related civil court procedures that are supposed to protect the defenseless, you’ve got, for instance, your liberals who’ll defend the process on principle, because they insist it must be preserved to protect the vulnerable, and they’ll fence-sit just to spite conservatives who flatly denounce the process as a governmental intrusion that undermines family.

Feminists, of course, are not thinking about all this psychology going on behind the scenes.

Feminists, of course, are not thinking about all this psychology going on behind the scenes. According to a

According to a

Her statement owns that “false reports [of rape] do really exist.” It also owns that they’re “incredibly damaging.” But it completely discounts the damage to the people falsely accused by those reports.

Her statement owns that “false reports [of rape] do really exist.” It also owns that they’re “incredibly damaging.” But it completely discounts the damage to the people falsely accused by those reports.

I grudgingly constructed a page this week on Facebook, which confirmed to me two things I already knew: (1) I really hate Facebook, and (2) women are more socially networked than men.

I grudgingly constructed a page this week on Facebook, which confirmed to me two things I already knew: (1) I really hate Facebook, and (2) women are more socially networked than men. Notice that 200 to 400 times greater interest in bonding with people concerned with women’s rights has been shown than interest in bonding with people concerned with men’s rights. That’s a lot…A LOT a lot.

Notice that 200 to 400 times greater interest in bonding with people concerned with women’s rights has been shown than interest in bonding with people concerned with men’s rights. That’s a lot…A LOT a lot.

I started to include the contents of this post in the last one, “

I started to include the contents of this post in the last one, “ It’s an attractively tidy idea and syncs up with feminist dogma nicely, but it’s critically shallow, besides ethically and empathically vacuous.

It’s an attractively tidy idea and syncs up with feminist dogma nicely, but it’s critically shallow, besides ethically and empathically vacuous. Those who posit that complainants of courthouse dirty dealings are predominately angry white men aren’t necessarily wrong, but they may be right for reasons they haven’t considered.

Those who posit that complainants of courthouse dirty dealings are predominately angry white men aren’t necessarily wrong, but they may be right for reasons they haven’t considered. a New York Jew. While neither one’s conclusions can be dismissed offhand, their cultural and class remove from the subjects of Dr. Kimmel’s book makes their identification with those subjects suspect, and Ms. Rosin’s objectivity and access are plainly dubious. From Ms. Rosin’s review: “Kimmel’s balance of critical distance and empathy works best in his chapter on the fathers’ rights movement, a subset of the men’s rights movement. Members of this group are generally men coming out of bitter divorce proceedings who believe the courts cheated them out of the chance to be close to their children.” Contrast this confidently categorical interpretation of men’s and fathers’ complaints to this firsthand account by a father who was ruined by “bitter divorce proceedings”: “

a New York Jew. While neither one’s conclusions can be dismissed offhand, their cultural and class remove from the subjects of Dr. Kimmel’s book makes their identification with those subjects suspect, and Ms. Rosin’s objectivity and access are plainly dubious. From Ms. Rosin’s review: “Kimmel’s balance of critical distance and empathy works best in his chapter on the fathers’ rights movement, a subset of the men’s rights movement. Members of this group are generally men coming out of bitter divorce proceedings who believe the courts cheated them out of the chance to be close to their children.” Contrast this confidently categorical interpretation of men’s and fathers’ complaints to this firsthand account by a father who was ruined by “bitter divorce proceedings”: “