“The first time ‘Misty’ broke into the backyard to pound and scream at the bedroom window, the police handcuffed her and said—her face pressed to the hood of the idling black-and-white—that she was not to return. I figured we would never see her again after that early morning in 2012. But the next night, around 1 a.m., I was in bed with my new boyfriend, ‘Scott,’ and we heard the bedroom door slowly crack open. Scott jumped up. ‘No! You can’t be here!’ he shouted, all high-pitched.”

—“This Restraining Order Expires on Tuesday”

Here’s a fascinating look at the female drama behind restraining orders. Its author is a gifted writer, and it’s an engaging read.

The subject of the piece, who’s called “Misty,” actually responds to it in the comments section—repeatedly—and calls some of its details into question, including ones that suggest speculation by the author (which, while imaginative, is nevertheless scrupulous and plausible). The writer, Natasha, was Misty’s rival in a love triangle. She apparently replaced Misty before Misty was prepared to relinquish her man.

That first night, [Scott and I] stayed at my house, and after having an intimate conversation in bed, we noticed his phone had 41 missed calls from Misty.

Then came the texts. She was at his house.

12:03 AM: Where are you? I’m staying here

12:05 AM: Please come back. I’m not going to lose you. I’m not going to give up. Please come back I want to see you. I love you

12:06 AM: I’m too drunk to drive home, can I please stay?

12:10 AM: Ok I’m staying.

Scott turned off the phone. The next morning when we checked again there were 16 more:

6:41 AM: By the way the pup tore the shit out of the house, but don’t worry I cleaned it up. If you can’t take care of him then you need to put him up for adoption.

To judge from Misty’s not contradicting the meat of the story (see the comments that follow it), its more titillating details are substantially accurate—and include serial calls and text messages to a nonresponsive ex, camping out in his yard, and even entering his house uninvited.

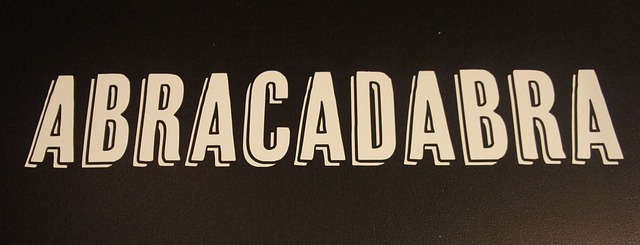

Hollywood representations like this one are seldom mirrored in real life. True “fatal attractions” are rare. High-conflict people, though, aren’t as rare as most imagine, which would be better known were their spiteful urges literally murderous (or even significantly violent). Attacks are typically insidious in their effects rather than bloody.

I tried to relax in Scott’s bed and just as I did, Misty appeared in the doorway.

“No! You can’t be here!” Scott cried, as he scrambled out of the sheets.

“I just came to see about the dog!” Misty shouted, rushing towards Scott.

Scott managed to wrangle Misty backwards away from the bed but she broke through and, before I could get fully to my feet, her arm swung back and I felt a fleshy thud against the side of my head.

She looked me in the eye, her nose ring glinting in the lamplight. “That’s what you get, you fat c[—],” she said.

She swooshed around, threw open the door (she had broken in through the window), and ran away into the night.

There was another series of confrontations with Misty but most of them took place in a courtroom, or through the unregulated space of fake Facebook profiles and anonymous emails. In the days after our first six-month order expired in 2013, Scott’s phone buzzed at 1 a.m.

It was a text message from Misty that just read: “Hi.”

Misty’s claim that her rival engaged in some passive-aggressive payback after a restraining order was procured also sounds credible:

Did you tell the people reading this article that you sent me a blank text from your boyfriend’s new phone during the restraining order period? I responded asking “who is this?” Natasha then proceeded to call the cops and told them I had violated the order. The judge laughed at it.

I’m no more a psychologist than Natasha, who chronicles the escapade, and I don’t know that her diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD) would be confirmed by a clinician, but I think there’s more than a hint of personality-disordered aggression in Misty’s conduct (that reported and that on display in the comments section beneath the story). Of the various personality disorders that typify high-conflict people, what’s more, BPD seems the best fit.

The individual with BPD demonstrates a wide range of impulsive behaviors, particularly those that are self destructive. BPD is characterized by wide mood swings, intense anger even at benign events, and idealization followed by devaluation. The BPD individual’s emotional life is a rollercoaster and his/her interpersonal relationships are particularly unstable. Typically, the individual with BPD has serious problems with boundaries. They become quickly involved in relationships with people, and then quickly become disappointed with them. They make great demands on other people, and easily become frightened of being abandoned by them.

Most suggestive of a disordered personality is the lack of shame or remorse in Misty’s responses. Her impulse is to blame, derogate, and punish:

One day I will laugh at her and said moron’s obese, ugly children and thank the lord they are not mine. I will defend myself to the end! A gigantic f[—] you to all is well deserved. I really can’t help the fact that she’s ugly. Jealousy is a horribly disease. I can’t really think of any other reason why she’d carry this drama on so long, they clearly talk about me. I’m flattered.

A high-conflict person may act impulsively—i.e., in hot blood—but having a personality disorder doesn’t mean someone is insane or psychotic. After an outburst of pique, rage may cool to mute hostility—which may nevertheless endure and continue to flare for years. (It’s perhaps telling, though, that wrathful women are often portrayed brandishing knives. It’s our go-to image for invoking vengeful malice.)

There’s a temptation to wonder whether all of this couldn’t have been resolved by talking things through. The reactions of the couple, like the behavior of Misty’s that motivated it, might be considered hysterical. On the other hand, had the man in the middle shown empathy and tried to assuage Misty’s feelings, he might have been the one who ended up on the receiving end of a restraining order.

This happens.

People like Misty are on both sides of restraining order and related prosecutions. Dare to imagine what Misty would be like as an accuser—the absence of conscience and the vengeful vehemence—and you’ll have an idea of what those who are falsely fingered as abusers are subject to. They’re menaced not by repeated home intrusions but by repeated abuses of process (false allegations to the police and court), which are at least as invasive and far more lasting and pernicious in their effects and consequences.

Something the story significantly highlights is feminine volatility. Feminism (itself often markedly hostile) would have us believe women are categorically passive, nurturing, and vulnerable. It’s men who are possessive, domineering, and dangerous.

The active agents in this story are the women; the guy (the “bone of contention”) is strictly peripheral.

Copyright © 2018 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*The author of RestrainingOrderBlog.com (now apparently defunct) alleged his accuser was a borderline personality.

Feminists, of course, are not thinking about all this psychology going on behind the scenes.

Feminists, of course, are not thinking about all this psychology going on behind the scenes.

whispered about then, can marry in a majority of states. When I was a kid, it was shaming for bra straps or underpants bands to be visible. Today they’re exposed on purpose.

whispered about then, can marry in a majority of states. When I was a kid, it was shaming for bra straps or underpants bands to be visible. Today they’re exposed on purpose. What once upon a time made this a worthy compromise of defendants’ constitutionally guaranteed expectation of

What once upon a time made this a worthy compromise of defendants’ constitutionally guaranteed expectation of  The account below, by Rosemary Anderson of Australia, was submitted to the e-petition End Restraining Order Abuses (since terminated by its host) and is highlighted here to show (1) that restraining orders are abused not only by intimates but by neighbors and strangers, (2) that the ease with which they’re applied for entices vexatious litigants (especially once their appetite has been whetted), and (3) that restraining orders are abused in countries other than the United States.

The account below, by Rosemary Anderson of Australia, was submitted to the e-petition End Restraining Order Abuses (since terminated by its host) and is highlighted here to show (1) that restraining orders are abused not only by intimates but by neighbors and strangers, (2) that the ease with which they’re applied for entices vexatious litigants (especially once their appetite has been whetted), and (3) that restraining orders are abused in countries other than the United States. The matter began when we opposed the expansion of their egg farm. We did so through the appropriate channels and in the appropriate manner. They have a CCW on their property and for reasons unknown were allowed to build the egg farm far too close to our boundary and house.

The matter began when we opposed the expansion of their egg farm. We did so through the appropriate channels and in the appropriate manner. They have a CCW on their property and for reasons unknown were allowed to build the egg farm far too close to our boundary and house. She once threatened my employer to get me sacked. I had luckily recorded several previous incidents that proved to my boss the lies they tell. They once took us to court over the boundary fence even though we had evidence in the form of letters and photos. Miraculously they won as they brought the non-professional fencing person with them as a witness. We weren’t given the appropriate notice by the court of their witness and could have selected several witnesses of our own to prove the fencing contractor assisted our neighbours to make a false insurance claim. The summons for this also came 18 months after we had given them what we had considered an appropriate payment. They had cashed the cheque and never contacted us in between to dispute it.

She once threatened my employer to get me sacked. I had luckily recorded several previous incidents that proved to my boss the lies they tell. They once took us to court over the boundary fence even though we had evidence in the form of letters and photos. Miraculously they won as they brought the non-professional fencing person with them as a witness. We weren’t given the appropriate notice by the court of their witness and could have selected several witnesses of our own to prove the fencing contractor assisted our neighbours to make a false insurance claim. The summons for this also came 18 months after we had given them what we had considered an appropriate payment. They had cashed the cheque and never contacted us in between to dispute it. I bonded with a client recently while wrestling a tough job to conclusion. I’ll call him “Joe.” Joe and I were talking in his backyard, and he confided to me that his next-door neighbor was “crazy.” She’d reported him to the police “about a 100 times,” he said, including for listening to music after dark on his porch.

I bonded with a client recently while wrestling a tough job to conclusion. I’ll call him “Joe.” Joe and I were talking in his backyard, and he confided to me that his next-door neighbor was “crazy.” She’d reported him to the police “about a 100 times,” he said, including for listening to music after dark on his porch.

Buncombe County, North Carolina, where

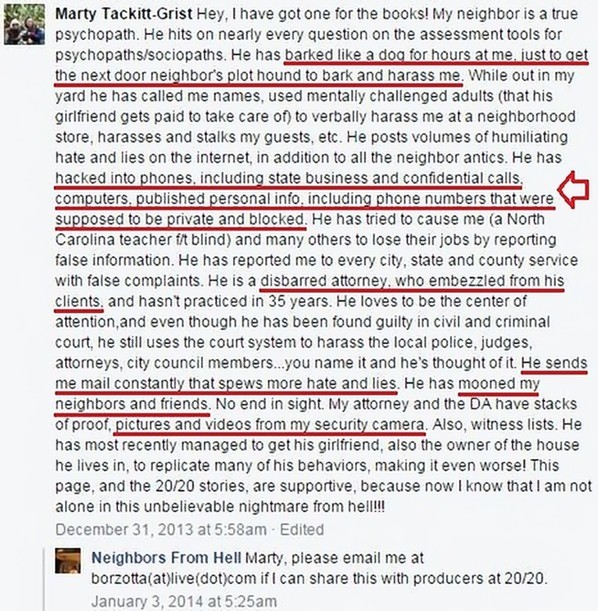

Buncombe County, North Carolina, where  She says he’s “barked like a dog” at her, recruited “mentally challenged adults” to harass her while shopping, and mooned her friends. She says he’s cyberstalked her, too, besides hacking into her phone and computer.

She says he’s “barked like a dog” at her, recruited “mentally challenged adults” to harass her while shopping, and mooned her friends. She says he’s cyberstalked her, too, besides hacking into her phone and computer. Here’s the reply the email elicited from ABC’s Bob Borzotta: “Hi Larry, I don’t seem to have heard further from her. Sounds like quite a situation….” Cursory validations like this one are the closest thing to solace that victims of chronic legal abuses can expect.

Here’s the reply the email elicited from ABC’s Bob Borzotta: “Hi Larry, I don’t seem to have heard further from her. Sounds like quite a situation….” Cursory validations like this one are the closest thing to solace that victims of chronic legal abuses can expect. The target of a high-conflict person is perpetually on the defensive, trying to recover his or her former life from the unrelenting grasp of a crank with an extreme (and often pathological) investment in eroding that life for self-aggrandizement and -gratification.

The target of a high-conflict person is perpetually on the defensive, trying to recover his or her former life from the unrelenting grasp of a crank with an extreme (and often pathological) investment in eroding that life for self-aggrandizement and -gratification. The ease with which a restraining order is obtained encourages outrageous defamations like these (Larry’s neighbor has sworn out two). Once a high-conflict person sees how readily

The ease with which a restraining order is obtained encourages outrageous defamations like these (Larry’s neighbor has sworn out two). Once a high-conflict person sees how readily

In the spring of 2011, she had been converting her home to a sort of boarding house and brought in tenants, and [between] them they had two cats that constantly prowled, especially the tenant’s. What became very irksome to me was the tenant’s cat creeping into our yard and killing our baby birds, which we always looked forward to in the spring. And the minute I brought it up with her, she pitched a fit, and so did the tenant. So for the first two months of baby bird season, [their] cats killed all our fledglings and the mother songbirds—wrens, cardinals, robins, mockingbirds, towhees, mourning doves, even the hummingbirds, just wiped them out. I finally got in touch with our Animal Services officers, but by that time bird season was over with, and you know something, [she] began going about telling neighbors that I was a disbarred lawyer (a particularly nasty slander). One thing led to another, and finally the tenant with the marauding cat moved away, but the irreparable damage was done, and all through the summer I had been warned by other neighbors that the neighbor from hell was plotting revenge.

In the spring of 2011, she had been converting her home to a sort of boarding house and brought in tenants, and [between] them they had two cats that constantly prowled, especially the tenant’s. What became very irksome to me was the tenant’s cat creeping into our yard and killing our baby birds, which we always looked forward to in the spring. And the minute I brought it up with her, she pitched a fit, and so did the tenant. So for the first two months of baby bird season, [their] cats killed all our fledglings and the mother songbirds—wrens, cardinals, robins, mockingbirds, towhees, mourning doves, even the hummingbirds, just wiped them out. I finally got in touch with our Animal Services officers, but by that time bird season was over with, and you know something, [she] began going about telling neighbors that I was a disbarred lawyer (a particularly nasty slander). One thing led to another, and finally the tenant with the marauding cat moved away, but the irreparable damage was done, and all through the summer I had been warned by other neighbors that the neighbor from hell was plotting revenge.

The lawyers quoted by reporter, what’s more, refer to criminal cases in which sexual abuse is alleged and, consequently, in which the accused are afforded attorney representation.

The lawyers quoted by reporter, what’s more, refer to criminal cases in which sexual abuse is alleged and, consequently, in which the accused are afforded attorney representation.

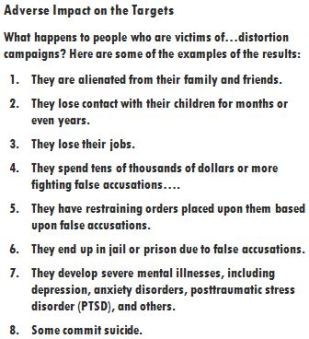

Faith in the conceit that restraining orders are minor impingements on defendants’ lives depends on accepting that being falsely, publically, and permanently labeled a stalker or batterer, for example, shouldn’t interfere with a person’s comfort, equanimity, or ability to realize his or her dreams. Such faith is founded, in other words, on the fantastical belief that wrongful vilification won’t exercise a detrimental influence on a person’s mental state, won’t affect his or her familial and social relationships, won’t negatively impact his or her employment and employability, etc.

Faith in the conceit that restraining orders are minor impingements on defendants’ lives depends on accepting that being falsely, publically, and permanently labeled a stalker or batterer, for example, shouldn’t interfere with a person’s comfort, equanimity, or ability to realize his or her dreams. Such faith is founded, in other words, on the fantastical belief that wrongful vilification won’t exercise a detrimental influence on a person’s mental state, won’t affect his or her familial and social relationships, won’t negatively impact his or her employment and employability, etc.

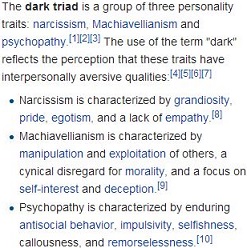

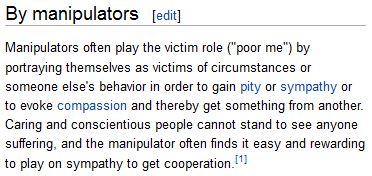

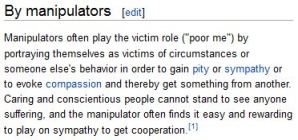

It turns out there’s a sexy phrase for the collective personality traits exhibited by manipulators of this sort: the “

It turns out there’s a sexy phrase for the collective personality traits exhibited by manipulators of this sort: the “

The Dark Triad traits should be associated with preferring casual relationships of one kind or another. Narcissism in particular should be associated with desiring a variety of relationships. Narcissism is the most social of the three, having an approach orientation towards friends (Foster & Trimm, 2008) and an externally validated ‘ego’ (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008). By preferring a range of relationships, narcissists are better suited to reinforce their sense of self. Therefore, although collectively the Dark Triad traits will be correlated with preferring different casual sex relationships, after controlling for the shared variability among the three traits, we expect that narcissism will correlate with preferences for one-night stands and friend[s]-with-benefits.

The Dark Triad traits should be associated with preferring casual relationships of one kind or another. Narcissism in particular should be associated with desiring a variety of relationships. Narcissism is the most social of the three, having an approach orientation towards friends (Foster & Trimm, 2008) and an externally validated ‘ego’ (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008). By preferring a range of relationships, narcissists are better suited to reinforce their sense of self. Therefore, although collectively the Dark Triad traits will be correlated with preferring different casual sex relationships, after controlling for the shared variability among the three traits, we expect that narcissism will correlate with preferences for one-night stands and friend[s]-with-benefits. What we’re talking about in the context of abuse of restraining orders are people who exploit others and then exploit legal process as a convenient means to discard them when they’re through (while whitewashing their own behaviors, procuring additional narcissistic supply in the forms of attention and special treatment, and possibly exacting a measure of revenge if they feel they’ve been criticized or contemned).

What we’re talking about in the context of abuse of restraining orders are people who exploit others and then exploit legal process as a convenient means to discard them when they’re through (while whitewashing their own behaviors, procuring additional narcissistic supply in the forms of attention and special treatment, and possibly exacting a measure of revenge if they feel they’ve been criticized or contemned). I tend to manipulate others to get my way.

I tend to manipulate others to get my way.

Judge Daniel Sanchez issued a restraining order against Letterman based on those allegations. By doing so, it put Letterman on a national list of domestic abusers, gave him a criminal record, took away several of his constitutionally protected rights, and subjected him to criminal prosecution if he contacted Nestler directly or indirectly, or possessed a firearm.

Judge Daniel Sanchez issued a restraining order against Letterman based on those allegations. By doing so, it put Letterman on a national list of domestic abusers, gave him a criminal record, took away several of his constitutionally protected rights, and subjected him to criminal prosecution if he contacted Nestler directly or indirectly, or possessed a firearm. To some degree at least, this understanding restricts all but the mentally ill, who may be delusional, and

To some degree at least, this understanding restricts all but the mentally ill, who may be delusional, and

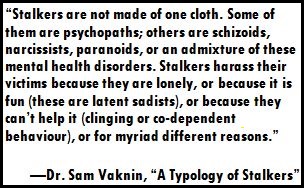

What a broader yet nuanced definition of stalking like Dr. Palmatier’s reveals is that what makes someone a stalker isn’t how his or her target perceives him or her; it’s how s/he perceives his or her target: as an object (what stalking literally means is the stealthy pursuit of prey—that is, food).

What a broader yet nuanced definition of stalking like Dr. Palmatier’s reveals is that what makes someone a stalker isn’t how his or her target perceives him or her; it’s how s/he perceives his or her target: as an object (what stalking literally means is the stealthy pursuit of prey—that is, food). Placed in proper perspective, then, not all acts of stalkers are rejected or alarming, because their targets don’t perceive their motives as deviant or predatory. The overtures of stalkers, interpreted as normal courtship behaviors, may be invited or even welcomed by the unsuspecting.

Placed in proper perspective, then, not all acts of stalkers are rejected or alarming, because their targets don’t perceive their motives as deviant or predatory. The overtures of stalkers, interpreted as normal courtship behaviors, may be invited or even welcomed by the unsuspecting. courts by disordered personalities as stalkers ignite in them the need to clear their names, on which their livelihoods may depend (never mind their sanity); and their determination, which for obvious reasons may be obsessive, seemingly corroborates stalkers’ false allegations of stalking.

courts by disordered personalities as stalkers ignite in them the need to clear their names, on which their livelihoods may depend (never mind their sanity); and their determination, which for obvious reasons may be obsessive, seemingly corroborates stalkers’ false allegations of stalking.

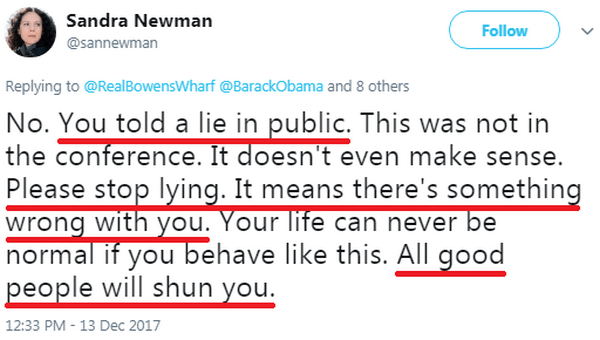

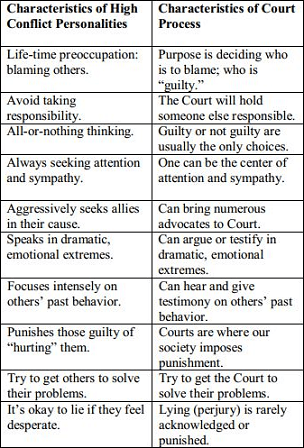

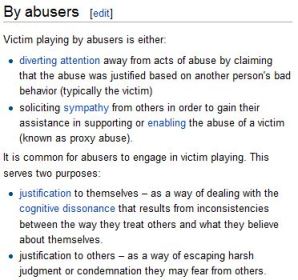

Contemplating these statements should also make clear the all-but-impossible task that counteracting the fraudulent allegations of high-conflict people can pose, both because disordered personalities lie without compunction and because they’re intensely invested in domination, blaming, and punishment.

Contemplating these statements should also make clear the all-but-impossible task that counteracting the fraudulent allegations of high-conflict people can pose, both because disordered personalities lie without compunction and because they’re intensely invested in domination, blaming, and punishment. I’ve read Freud, Lacan, and some other abstruse psychology texts, because I was trained as a literary analyst, and psychological theories are sometimes used by textual critics as interpretive prisms. None of these equipped me, though, to understand the kind of person who would wantonly lie to police officers and judges, enlist others in smear campaigns, and/or otherwise engage in dedicatedly vicious misconduct.

I’ve read Freud, Lacan, and some other abstruse psychology texts, because I was trained as a literary analyst, and psychological theories are sometimes used by textual critics as interpretive prisms. None of these equipped me, though, to understand the kind of person who would wantonly lie to police officers and judges, enlist others in smear campaigns, and/or otherwise engage in dedicatedly vicious misconduct.

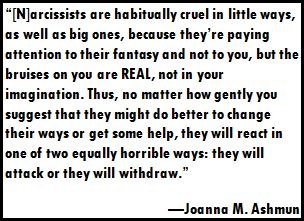

If you’ve been attacked serially by someone you trusted who’s abused legal process to hurt you, spread false rumors about you, made false allegations against you, and otherwise manipulated others to join in bullying you (possibly over a period spanning years and despite your reasonable attempts to settle the situation), your persecutor is an example of the high-conflict person to whom the epigraph refers, and understanding his or her motives may be of value to your self-protection.

If you’ve been attacked serially by someone you trusted who’s abused legal process to hurt you, spread false rumors about you, made false allegations against you, and otherwise manipulated others to join in bullying you (possibly over a period spanning years and despite your reasonable attempts to settle the situation), your persecutor is an example of the high-conflict person to whom the epigraph refers, and understanding his or her motives may be of value to your self-protection. The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin I’ve quoted goes on at some length to detail the difficulties and complexities that unraveling false claims entails for agents of the FBI. Appreciate then how absurd is the state’s faith that a single judge—or a couple of them—can ascertain the truth of civil restraining order allegations by auditing claims in a hearing or hearings arrived at with no prior information, that last mere minutes, and that are furthermore biased by the preconception that the accused is guilty.

The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin I’ve quoted goes on at some length to detail the difficulties and complexities that unraveling false claims entails for agents of the FBI. Appreciate then how absurd is the state’s faith that a single judge—or a couple of them—can ascertain the truth of civil restraining order allegations by auditing claims in a hearing or hearings arrived at with no prior information, that last mere minutes, and that are furthermore biased by the preconception that the accused is guilty.

What I discovered was that group-bullying certainly is a recognized social phenomenon among kids, and it’s one that’s given rise to the coinage cyberbullying and been credited with inspiring teen suicide. The clinical term for this conduct is

What I discovered was that group-bullying certainly is a recognized social phenomenon among kids, and it’s one that’s given rise to the coinage cyberbullying and been credited with inspiring teen suicide. The clinical term for this conduct is

In “

In “

In fact, what it and any number of others’ ordeals show is that when you offer people an easy means to excite drama and conflict, they’ll exploit it.

In fact, what it and any number of others’ ordeals show is that when you offer people an easy means to excite drama and conflict, they’ll exploit it.