“I became suspicious of my own traits after extended contact with another sociopath, with whom I clicked instantly.”

—Clinically diagnosed sociopath

The above remark in an online forum caught my eye, because it validated a suspicion I’ve nursed that sociopathic people identify with and gravitate toward one another. It’s predictable, really, that people with common perspectives should be mutually attracted, as well as drawn to particular fields, for a couple of examples, institutional research and law. Italics that appear in the quoted paragraphs below, which are by the same male speaker, are added. This speaker, whose comments will be illuminating to students of anomalous brains, is not the author of the book whose cover is used as illustration.

“Generally our impulsive and charismatic personalities mean we become friends easily. For example, both of my flatmates are sociopathic, although probably to a lesser degree than myself. I’m able to freely talk with them about manipulative behavior, and we occasionally teach each other tricks based on our own areas of social expertise. Working as a group, we can very easily mask one another and cooperate to more effectively manipulate others. We also mutually operate on the same rationally motivated, prosocial basis, and as a result we find it very easy to trust one another as our motivations are all identical, and we’re aware of that.

“Generally our impulsive and charismatic personalities mean we become friends easily. For example, both of my flatmates are sociopathic, although probably to a lesser degree than myself. I’m able to freely talk with them about manipulative behavior, and we occasionally teach each other tricks based on our own areas of social expertise. Working as a group, we can very easily mask one another and cooperate to more effectively manipulate others. We also mutually operate on the same rationally motivated, prosocial basis, and as a result we find it very easy to trust one another as our motivations are all identical, and we’re aware of that.

“An awful lot of my sociopathic friends are aware, because I had the conversation with them and ‘woke them up.’ I tend to deliberately gather other socios around me and then make them self-aware, which has created a very interesting little social circle around me. We talk about it quite regularly, because it often comes up when we’re venting to each other or discussing our emotional responses.

“Academia is full of narcissists and sociopaths. So is the legal profession. Virtually any ‘prestigious’ career that offers a lot of potential cash will contain socios, but at the same time there will be some of us almost anywhere as many socios choose the easiest lifestyle possible, which isn’t compatible with those sorts of high-level careers. All fringe subcultures have a higher than average representation of socios, and the drug subculture is absolutely infested with them.”

Reading this person’s analysis of the differences between sociopaths and narcissists, which is very self-aware and forthcoming, was equally interesting, and those who’ve been traumatized by personalities of these types, may also find it significant.

“It’s the difference between ‘I am better than those around me’ and ‘I am fundamentally different [from] those around me, because I have a bizarre and somewhat broken brain.’ Narcissists believe they excel because they’re amazing at everything; sociopaths accept that we’re cheating.

“I very rapidly psychoanalyze others and then use their self-image and insecurities against them. For example, say I spot a woman who’s very insecure and in need of male validation. I can compliment her in exactly the way she wants and needs, and as a result foster emotional dependence, which can give me what I want. Or if you’re badly educated and insecure about your intelligence, I’ll show interest in you as an intelligent and well educated man, and tell you how smart I think you are and how much potential you secretly have, and as a result you’ll end [up] feeling ‘special’ and get the feelings of excellence you crave. Which can give me what I want. Etc., etc. It would take a very long time to explain every possible outcome, but generally it relies on telling people what they want to hear. This is my style, though, and some other socios can be VERY different. Female sociopaths tend to use self-victimization and foster ‘white knight’ behavior in men above all else, for example.

“I can be very passionate about some things, and that’s genuine. I care about my closer friends (because they’re mine) and the women I’m sleeping with (because they’re mine). I avoid negatively affecting those people at all and can actually be very, very protective of them—which in practice ends up being a mutually beneficial relationship.”

This person also validated my conviction that narcissists possess a far greater potential to damage others.

“I f*cking hate narcissists. They’re even worse than us, and they manage to delude themselves into believing that they’re the nicest people on earth. I hate the effect they have on other people, because it’s completely, needlessly damaging, and my own ethics are utilitarian, so the sort of wastefully cruel behavior they participate in just strikes me as stupid and childish.”

He corroborates the most basic defining attributes of the sociopath—and the character traits and tendencies he limns are ones familiar to me as a daily reader of people’s ordeals with sociopathic partners or former partners.

“I don’t feel any guilt. I have no idea what guilt even feels like. I have very few emotions at all. Most of my social interactions with non-socios are pure acting. I also have the full-on stereotypical predatory stare unless I remind myself to ‘act’ as if I’m making normal eye contact, which is a dead giveaway. I feel like most people are just zombies rather than real human beings at all.

“I don’t have a conscience. I use the word hate all the time, but I’m not sure I know what it truly means, to be honest.

“Most of my emotions are what is described as ‘shallow’—that is, they are short-lived, theatrical, and don’t affect my thought processes to the same degree as a normal person. Anger is heightened, and I have a capacity for truly blind rage. I have fallen in what I perceived as ‘love’ with another sociopath in the past, but whether that was mutual obsession or what a neurotypical person would describe as ‘love’ is a mystery to me, although I did care about her deeply.

“We’re almost invariably very smart and possessed of higher than average verbal and social intelligence. Acting is just…easy, for us, for some reason. It’s something we all seem to learn naturally. It is absolutely just acting, and if you can watch a professional actor bring tears on command then you understand how we do it.

“I think all sociopaths get off on power. We tend to view ourselves as distinct from other people (in a way that very easily slips into narcissism) and as ‘natural leaders’ (which we sort of are, in all fairness), and we enjoy being in those positions. I enjoy success, and I enjoy demonstrating that I’m more able than others. Sexually, I tend towards being extremely dominant and aggressive; however, I’d rather find submissives who enjoy that experience than shoot myself in the foot by needlessly harming other people. I think this need to demonstrate dominance over others is inherent, but you can deal with it in different ways; I’d rather be heavily involved in BDSM and a careerist assh*le than satisfy my need for dominance by needlessly murdering other human beings, but I do suspect that that need is why the most maladjusted and broken sociopathic individuals sometimes deliberately harm others for kicks, or even kill.

“Fringe sexual preferences [are] virtually ubiquitous. They don’t bother me at all, because they’re really fun—and drug use allows me to experience some of the emotional extremes that I would otherwise be denied.”

He also contradicts the psychopath stereotype.

“Animals love me for some reason. Cats especially will always pick me to sit on if there [are] multiple people in the room. Dogs respond to my eye contact and mannerisms by being very submissive.

“I like cats and dogs, and I enjoy having them around, so I don’t see any reason to hurt them. The idea of hurting an animal does not make me feel guilty at all, but I do see it as unpleasant.”

His derision of narcissists betrays resentment that sociopaths should be popularly or psychologically associated with these undisciplined and self-delusory slaves to their compulsions. Below is his response to the inquiry, “In your [opinion], do narcissists a) know fully that they’re lying when they’re gaslighting you? b) truly believe the twisted version of reality they present you with, or c) talk themselves into believing their own lies gradually because it suits them? This question is something that causes me a lot of pain and confusion when being gaslighted. Some part of me still wants to believe they are good people without malice….”

His derision of narcissists betrays resentment that sociopaths should be popularly or psychologically associated with these undisciplined and self-delusory slaves to their compulsions. Below is his response to the inquiry, “In your [opinion], do narcissists a) know fully that they’re lying when they’re gaslighting you? b) truly believe the twisted version of reality they present you with, or c) talk themselves into believing their own lies gradually because it suits them? This question is something that causes me a lot of pain and confusion when being gaslighted. Some part of me still wants to believe they are good people without malice….”

”This depends on exactly how self-deluding any given narcissist is, and from an external perspective it’s very hard to tell. I avoid gaslighting [see footnote]…but if I [were] to do it, I’d be fully aware that I was lying. On the other hand, narcissists are extremely unlikely to ever admit it to themselves, because their entire self-perception is completely distorted. It’s likely to be a combination of B + C in practice; A would be behavior more characteristic of a true sociopath. Keep in mind that narcissism is a sliding scale of self-delusion in practice; the worst examples will be B, but the majority are likely to be C. A narcissist is just a sociopath who believes [his or her] own bullshit, really. I wouldn’t say they’re ‘good people’ but they’re not fully conscious of what they’re doing.

“Assume everything they say is bullshit until you see at least some evidence. You don’t have to tell them this, but be absolutely cynical.

“Any extreme displays of emotion are not real.

“Do NOT do anything to give them any more power over you than they have—lending or borrowing money, making minor concessions, etc. They will use it against you.

“Narcissists have incredibly unstable self-esteem. Keep this in mind, and you may be able to motivate them into doing what you want to some degree.

“I think sociopaths are born, and narcissists are made from some of those sociopaths. I don’t think every person has the potential to be a true narcissist based on nurture. People who are naturally ‘sociopathic’ aren’t evil, because we can be incredibly socially symbiotic if we’re aware of the value of prosocial behavior.”

It’s fascinating to me to contrast my impression of this highly intelligent man, who’s a self-acknowledged sociopath with a reasoned code of ethics, with what I know of the narcissist, who’s a parasitic sponge and chronic and impulsive liar. The narcissist is infantile; designing, perfidious, and fraudulent to the core; and wantonly vengeful and destructive. This man, who’s clearly very singular in his self-awareness, lucidness, and honesty may be a sociopath, but after observing how willfully “neurotypical” people lie and treacherously betray others, I’d much sooner trust his motives and integrity than theirs.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

Wikipedia: “Gaslighting is a form of mental abuse in which false information is presented with the intent of making a victim doubt his or her own memory, perception, and sanity. Instances may range simply from the denial by an abuser that previous abusive incidents ever occurred up to the staging of bizarre events by the abuser with the intention of disorienting the victim.”

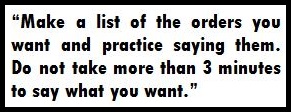

There’s nevertheless value in bringing systemic injustices to the attention of legislators (senators and congressmen and -women), because (1) they make, reform, and repeal laws, and (2) if they hear the same complaints over and over—and especially if they know other people of influence are hearing the same complaints and looking to them for action—there’s a chance some of them might step up.

There’s nevertheless value in bringing systemic injustices to the attention of legislators (senators and congressmen and -women), because (1) they make, reform, and repeal laws, and (2) if they hear the same complaints over and over—and especially if they know other people of influence are hearing the same complaints and looking to them for action—there’s a chance some of them might step up. “

“ The lawyers quoted by reporter, what’s more, refer to criminal cases in which sexual abuse is alleged and, consequently, in which the accused are afforded attorney representation.

The lawyers quoted by reporter, what’s more, refer to criminal cases in which sexual abuse is alleged and, consequently, in which the accused are afforded attorney representation.

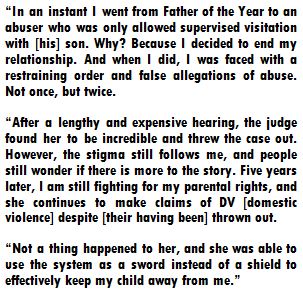

Faith in the conceit that restraining orders are minor impingements on defendants’ lives depends on accepting that being falsely, publically, and permanently labeled a stalker or batterer, for example, shouldn’t interfere with a person’s comfort, equanimity, or ability to realize his or her dreams. Such faith is founded, in other words, on the fantastical belief that wrongful vilification won’t exercise a detrimental influence on a person’s mental state, won’t affect his or her familial and social relationships, won’t negatively impact his or her employment and employability, etc.

Faith in the conceit that restraining orders are minor impingements on defendants’ lives depends on accepting that being falsely, publically, and permanently labeled a stalker or batterer, for example, shouldn’t interfere with a person’s comfort, equanimity, or ability to realize his or her dreams. Such faith is founded, in other words, on the fantastical belief that wrongful vilification won’t exercise a detrimental influence on a person’s mental state, won’t affect his or her familial and social relationships, won’t negatively impact his or her employment and employability, etc.

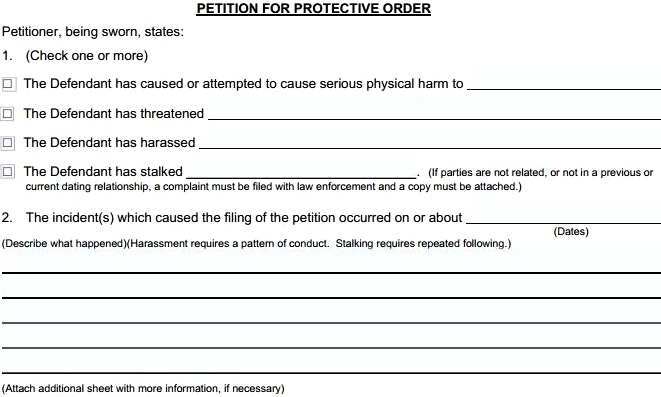

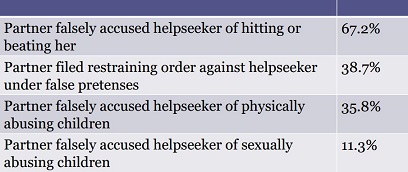

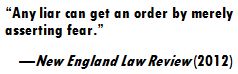

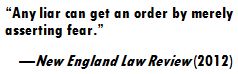

All there is to making allegations on restraining orders is tick boxes and blanks, and there are no bounds imposed upon what allegations can be made. A false applicant merely writes whatever he wants in the spaces provided—and he can use additional pages if he’s feeling inspired. The basis for a woman’s being alleged to be a domestic abuser or even “armed and dangerous” is the unsubstantiated say-so of the petitioner. Can the defendant be a vegetarian single mom or an arthritic, 80-year-old great-grandmother? Sure. The judge who rules on the application won’t have met her and may never even learn what she looks like. She’s just a name.

All there is to making allegations on restraining orders is tick boxes and blanks, and there are no bounds imposed upon what allegations can be made. A false applicant merely writes whatever he wants in the spaces provided—and he can use additional pages if he’s feeling inspired. The basis for a woman’s being alleged to be a domestic abuser or even “armed and dangerous” is the unsubstantiated say-so of the petitioner. Can the defendant be a vegetarian single mom or an arthritic, 80-year-old great-grandmother? Sure. The judge who rules on the application won’t have met her and may never even learn what she looks like. She’s just a name.

Judge Daniel Sanchez issued a restraining order against Letterman based on those allegations. By doing so, it put Letterman on a national list of domestic abusers, gave him a criminal record, took away several of his constitutionally protected rights, and subjected him to criminal prosecution if he contacted Nestler directly or indirectly, or possessed a firearm.

Judge Daniel Sanchez issued a restraining order against Letterman based on those allegations. By doing so, it put Letterman on a national list of domestic abusers, gave him a criminal record, took away several of his constitutionally protected rights, and subjected him to criminal prosecution if he contacted Nestler directly or indirectly, or possessed a firearm. To some degree at least, this understanding restricts all but the mentally ill, who may be delusional, and

To some degree at least, this understanding restricts all but the mentally ill, who may be delusional, and

I’ll give you a for-instance. Let’s say Person A applies for a protection order and claims Person B threatened to rape her and then kill her with a butcher knife.

I’ll give you a for-instance. Let’s say Person A applies for a protection order and claims Person B threatened to rape her and then kill her with a butcher knife. Person A circulates the details she shared with the court, which are embellished and further honed with repetition, among her friends and colleagues over the ensuing days, months, and years.

Person A circulates the details she shared with the court, which are embellished and further honed with repetition, among her friends and colleagues over the ensuing days, months, and years.

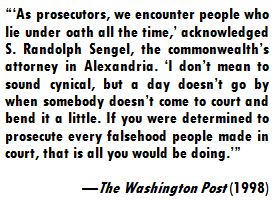

Scholars, members of the clergy, and practitioners of disciplines like medicine, science, and the law, among others from whom we expect scrupulous truthfulness and a contempt for deception, are furthermore no more above lying (or actively or passively abetting fraud) than anyone else.

Scholars, members of the clergy, and practitioners of disciplines like medicine, science, and the law, among others from whom we expect scrupulous truthfulness and a contempt for deception, are furthermore no more above lying (or actively or passively abetting fraud) than anyone else. M.D., Ph.D., Th.D., LL.D.—no one is above lying, and the fact is the better a liar’s credentials are, the more ably s/he expects to and can pull the wool over the eyes of judges, because in the political arena judges occupy, titles carry weight: might makes right.

M.D., Ph.D., Th.D., LL.D.—no one is above lying, and the fact is the better a liar’s credentials are, the more ably s/he expects to and can pull the wool over the eyes of judges, because in the political arena judges occupy, titles carry weight: might makes right. The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin I’ve quoted goes on at some length to detail the difficulties and complexities that unraveling false claims entails for agents of the FBI. Appreciate then how absurd is the state’s faith that a single judge—or a couple of them—can ascertain the truth of civil restraining order allegations by auditing claims in a hearing or hearings arrived at with no prior information, that last mere minutes, and that are furthermore biased by the preconception that the accused is guilty.

The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin I’ve quoted goes on at some length to detail the difficulties and complexities that unraveling false claims entails for agents of the FBI. Appreciate then how absurd is the state’s faith that a single judge—or a couple of them—can ascertain the truth of civil restraining order allegations by auditing claims in a hearing or hearings arrived at with no prior information, that last mere minutes, and that are furthermore biased by the preconception that the accused is guilty.

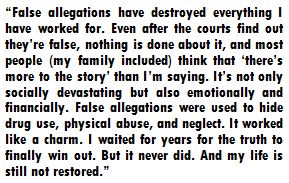

The very real if inconvenient truth remains that victims of false allegations made to authorities and the courts present with the same symptoms highlighted in the epigraph: “fear, anxiety, nervousness, self-blame, anger, shame, and difficulty sleeping”—among a host of others. And that’s just the ones who aren’t robbed of everything that made their lives meaningful, including home, property, and family. In the latter case, post-traumatic stress disorder may be the least of their torments. They may be left homeless, penniless, childless, and emotionally scarred.

The very real if inconvenient truth remains that victims of false allegations made to authorities and the courts present with the same symptoms highlighted in the epigraph: “fear, anxiety, nervousness, self-blame, anger, shame, and difficulty sleeping”—among a host of others. And that’s just the ones who aren’t robbed of everything that made their lives meaningful, including home, property, and family. In the latter case, post-traumatic stress disorder may be the least of their torments. They may be left homeless, penniless, childless, and emotionally scarred.

In fact, what it and any number of others’ ordeals show is that when you offer people an easy means to excite drama and conflict, they’ll exploit it.

In fact, what it and any number of others’ ordeals show is that when you offer people an easy means to excite drama and conflict, they’ll exploit it. Her coterie of girlfriends is transposed straight from the halls of high school. They’re less physically favored than the leader of their pack and content to warm themselves in her aura. The adolescent intrigue injects some color into their treadmill lives, and they savor the vicarious thrill of the hunt. The man is a topic of their daily conversation. The women feel young again for a few months, like conspirators in an unconsummated teen crush.

Her coterie of girlfriends is transposed straight from the halls of high school. They’re less physically favored than the leader of their pack and content to warm themselves in her aura. The adolescent intrigue injects some color into their treadmill lives, and they savor the vicarious thrill of the hunt. The man is a topic of their daily conversation. The women feel young again for a few months, like conspirators in an unconsummated teen crush. The life of the man who’d hospitably welcomed the strangers, shaking hands in good faith and doling out mugs of cheer, is trashed: multiple trips to the police precinct to answer false charges and appeals to the court that only invite censure and further abuse. His record, formerly that of an invisible man, becomes hopelessly corrupted. His artistic endeavor, a labor of love that he’d plied himself at for years and on which he’d banked his future joy and financial comfort, is predictably derailed.

The life of the man who’d hospitably welcomed the strangers, shaking hands in good faith and doling out mugs of cheer, is trashed: multiple trips to the police precinct to answer false charges and appeals to the court that only invite censure and further abuse. His record, formerly that of an invisible man, becomes hopelessly corrupted. His artistic endeavor, a labor of love that he’d plied himself at for years and on which he’d banked his future joy and financial comfort, is predictably derailed. A man eyes a younger, attractive woman at work every day. She’s impressed by him, also, and reciprocates his interest. They have a brief sexual relationship that, unknown to her, is actually an extramarital affair, because the man is married. The younger woman, having naïvely trusted him, is crushed when the man abruptly drops her, possibly cruelly, and she then discovers he has a wife. Maybe she openly confronts him at work. Maybe she calls or texts him. Maybe repeatedly. The man, concerned to preserve appearances and his marriage, applies for a restraining order alleging the woman is harassing him, has become fixated on him, is unhinged. As evidence, he provides phone records, possibly dating from the beginning of the affair—or pre-dating it—besides intimate texts and emails. He may also provide tokens of affection she’d given him, like a birthday card the woman signed and other romantic trifles, and represent them as unwanted or even (implicitly) disturbing. “I’m a married man, Your Honor,” he testifies, admitting nothing, “and this woman’s conduct is threatening my marriage, besides my status at work.”

A man eyes a younger, attractive woman at work every day. She’s impressed by him, also, and reciprocates his interest. They have a brief sexual relationship that, unknown to her, is actually an extramarital affair, because the man is married. The younger woman, having naïvely trusted him, is crushed when the man abruptly drops her, possibly cruelly, and she then discovers he has a wife. Maybe she openly confronts him at work. Maybe she calls or texts him. Maybe repeatedly. The man, concerned to preserve appearances and his marriage, applies for a restraining order alleging the woman is harassing him, has become fixated on him, is unhinged. As evidence, he provides phone records, possibly dating from the beginning of the affair—or pre-dating it—besides intimate texts and emails. He may also provide tokens of affection she’d given him, like a birthday card the woman signed and other romantic trifles, and represent them as unwanted or even (implicitly) disturbing. “I’m a married man, Your Honor,” he testifies, admitting nothing, “and this woman’s conduct is threatening my marriage, besides my status at work.”

Victims of false allegations made on restraining orders may be labeled “stalker,” “batterer,” “sicko,” “sexual harasser,” “child-abuser,” “whore,” or even “rapist”—publicly and permanently—by accusers whose sole motive is to brutalize. And agents of these victims’ own government(s) arbitrarily authorize this bullying and may baselessly and basely participate in it, compounding the injury exponentially.

Victims of false allegations made on restraining orders may be labeled “stalker,” “batterer,” “sicko,” “sexual harasser,” “child-abuser,” “whore,” or even “rapist”—publicly and permanently—by accusers whose sole motive is to brutalize. And agents of these victims’ own government(s) arbitrarily authorize this bullying and may baselessly and basely participate in it, compounding the injury exponentially.

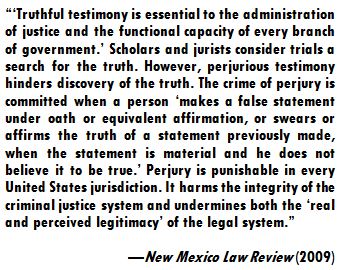

Many restraining order recipients are brought to this site wondering how to recover damages for false allegations and the torments and losses that result from them. Not only is perjury (lying to the court) never prosecuted; it’s never explicitly acknowledged. The question arises whether false accusers

Many restraining order recipients are brought to this site wondering how to recover damages for false allegations and the torments and losses that result from them. Not only is perjury (lying to the court) never prosecuted; it’s never explicitly acknowledged. The question arises whether false accusers  I understand her very well, but at the risk of pointing out the obvious, she shouldn’t have to. False allegations aren’t a withered limb, a ruptured disc, or an autoimmune disease. These latter things are real and unavoidable. Lies aren’t real, and their pain is easily relieved. The lies just have to be rectified.

I understand her very well, but at the risk of pointing out the obvious, she shouldn’t have to. False allegations aren’t a withered limb, a ruptured disc, or an autoimmune disease. These latter things are real and unavoidable. Lies aren’t real, and their pain is easily relieved. The lies just have to be rectified.

Playing the victim is a very potent form of passive aggression when the audience includes authorities and judges. Validation from these audience members is particularly gratifying to the egos of frauds, and both the police and judges have been trained to respond gallantly to the appeals of “damsels in distress.”

Playing the victim is a very potent form of passive aggression when the audience includes authorities and judges. Validation from these audience members is particularly gratifying to the egos of frauds, and both the police and judges have been trained to respond gallantly to the appeals of “damsels in distress.” One of the aforementioned teachers was on his way to Nashville to become a songwriter, that is, a creative artist. Any career in the public eye like this one is vulnerable to being compromised or trashed by a scandal that may be based on nothing but cunning lies or a disturbed person’s fantasies spewed impulsively in a window of five or 10 minutes. Besides the obvious impairment that something like this can exert on income prospects, its psychological effects alone can make performance of a job impossible. And nothing kills income prospects more surely than that.

One of the aforementioned teachers was on his way to Nashville to become a songwriter, that is, a creative artist. Any career in the public eye like this one is vulnerable to being compromised or trashed by a scandal that may be based on nothing but cunning lies or a disturbed person’s fantasies spewed impulsively in a window of five or 10 minutes. Besides the obvious impairment that something like this can exert on income prospects, its psychological effects alone can make performance of a job impossible. And nothing kills income prospects more surely than that. Although men regularly abuse the restraining order process, it’s more likely that tag-team offensives will be by women against men. Women may be goaded on by their parents or siblings, by authorities, by girlfriends, or by dogmatic women’s advocates. The expression of discontentment with a partner may be regarded as grounds enough for exploiting the system to gain a dominant position. These women may feel obligated to follow through to appease peer or social expectations. Or they may feel pumped up enough by peer or social support to follow through on a spiteful impulse. Girlfriends’ responding sympathetically, whether to claims of quarreling with a spouse or boy- or girlfriend or to claims that are clearly hysterical or even preposterous, is both a natural female inclination and one that may steel a false or frivolous complainant’s resolve.

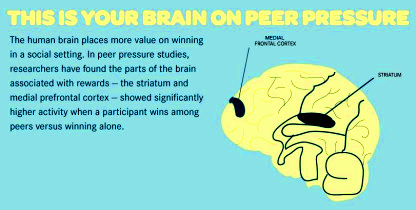

Although men regularly abuse the restraining order process, it’s more likely that tag-team offensives will be by women against men. Women may be goaded on by their parents or siblings, by authorities, by girlfriends, or by dogmatic women’s advocates. The expression of discontentment with a partner may be regarded as grounds enough for exploiting the system to gain a dominant position. These women may feel obligated to follow through to appease peer or social expectations. Or they may feel pumped up enough by peer or social support to follow through on a spiteful impulse. Girlfriends’ responding sympathetically, whether to claims of quarreling with a spouse or boy- or girlfriend or to claims that are clearly hysterical or even preposterous, is both a natural female inclination and one that may steel a false or frivolous complainant’s resolve.

“If we did prosecute perjurers, there’d be no resources left for putting dangerous people behind bars…so we’ll prosecute the people perjurers falsely accuse of being dangerous”—as analysis of most of the arguments made in defense of domestic violence and restraining order policies reveals, the reasoning is circular and smells foul. It’s in fact unreasoned “reasoning” that’s really just something to say to distract attention from unflattering truths that don’t win elections, federal grants, popular esteem, or political favor. So entrenched are these policies and so megalithic (and lucrative) that rhetoric like this actually passes for satisfactory when it’s used by someone in a crisp suit with a crisper title.

“If we did prosecute perjurers, there’d be no resources left for putting dangerous people behind bars…so we’ll prosecute the people perjurers falsely accuse of being dangerous”—as analysis of most of the arguments made in defense of domestic violence and restraining order policies reveals, the reasoning is circular and smells foul. It’s in fact unreasoned “reasoning” that’s really just something to say to distract attention from unflattering truths that don’t win elections, federal grants, popular esteem, or political favor. So entrenched are these policies and so megalithic (and lucrative) that rhetoric like this actually passes for satisfactory when it’s used by someone in a crisp suit with a crisper title. The restraining order process has become a perfunctory routine verging on a skit, a scripted pas de deux between a judge and a complainant. Exposure of the iniquity of this procedural farce hardly requires commentary.

The restraining order process has become a perfunctory routine verging on a skit, a scripted pas de deux between a judge and a complainant. Exposure of the iniquity of this procedural farce hardly requires commentary. The answer to these questions is of course known to (besides men) any number of women who’ve been victimized by the restraining order process. They’re not politicians, though. Or members of the ivory-tower club that determines the course of what we call mainstream feminism. They’re just the people who actually know what they’re talking about, because they’ve been broken by the state like butterflies pinned to a board and slowly vivisected with a nickel by a sadistic child.

The answer to these questions is of course known to (besides men) any number of women who’ve been victimized by the restraining order process. They’re not politicians, though. Or members of the ivory-tower club that determines the course of what we call mainstream feminism. They’re just the people who actually know what they’re talking about, because they’ve been broken by the state like butterflies pinned to a board and slowly vivisected with a nickel by a sadistic child.