“[W]hy would someone lie about being sexually assaulted? What could be gained from that? Nothing, really.”

—Tracie Egan Morrissey, Jezebel (Feb. 28, 2014)

The quotation above derives from a piece titled, “Rape, Lies and the Internet: The Story of Conor Oberst and His Accuser.” It’s spotlighted because it echoes the sentiment expressed by the writer of the prior post’s epigraph, who’s also a feminist and who betrays the same blindness.

What’s disturbing to the author of the blog you’re reading is that feminists who ask questions like Ms. Morrissey’s make a strong case for rape denial, because it might just as unreasonably be asked, “Why would someone sexually assault anyone? What could be gained from that?”

What could be “gained” from raping someone is the same thing that could be “gained” from lying about being raped—or lying about any number of other offenses: the exultation of control (i.e., power, dominance).

Other reasons for lying suggested by Ms. Morrisey’s own reportage are attention-seeking, self-aggrandizement, and mythomania. There have also been a number of publicized cases about false rape accusations’ being used for concealment of sexual infidelity. Two hyperlinks in this post lead to stories exemplifying this motive. Of course (and significantly), none of these motives applies exclusively to false rape claims. Besides avarice and malice, they’re common motives among false accusers (of all types). People hurt people…to hurt people. Appetites, least of all vicious ones, don’t answer to sense.

The previous post emphasized the emotional trauma of accusation, particularly false accusation, by highlighting a number of suicides reported in the news.

Suicide is a recognized consequence of bullying; name-calling and public humiliation are recognized as among the forms that bullying takes; and falsely branding someone a stalker, rapist, child abuser, or killer, for example, certainly qualifies as publicly humiliating name-calling.

Whether someone is disparaged on the playground, on Facebook, in a courtroom, or in the headlines makes absolutely no difference; the effect is the same, and it may be unbearable.

This stuff shouldn’t need to be pointed out to grown-ups. But since the fatal consequences of false accusation don’t support any dominant political agendas—and may undermine them—they’re ignored. That people are harried and hectored by lies, sometimes to death, is an inconvenient truth.

At least it is here. Many of the news clippings featured in the last post notably originate from the U.K., as do two of the clippings below. Journalism is far more balanced there, and it’s less taboo to call a jade a jade. A Jezebel reporter might denounce this as “misogynistic,” but truth isn’t misogynistic; it’s just the truth, and it doesn’t play favorites (nor should its purveyors).

This post looks at the other lethal upshot of false accusation: murder. The stories that follow are about people who existed and now do not.

The point of introducing these stories isn’t to assert incidents like these are common; the point is to reveal the emotions that are inspired by false accusations, whether by women, by men, or by mobs. It’s also to reveal their consequences…writ large and lurid. These same emotions are aroused in cops and judges no less than they are in anyone else. False accusers know what reactions they can expect, and they know how to manipulate their audience—and bending others to do their will is thrilling.

Nothing makes the emotions provoked by accusation more manifest than when accusation inspires others to beat someone to death—or set him ablaze.

This is nevertheless typically lost on reporters and their viewers and readers. The details that are stressed and eagerly sought are who got it, and how. Why, which is always the more speculative aspect, is in its broader implications the most important one, however.

Gore is sexy. It’s what gets airplay and column space. It’s an attention-grabber and a ratings booster. Nothing draws the eye like the color red.

What sensation eclipses, though, is that for every false accusation that ends in red, thousands or hundreds of thousands end in gray, an interminable state of disquiet, disease, and dolor.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*Jezebel, if I’m remembering my Bible stories right, was a mass murderer who was condemned for promoting a false dogma. (Among her victims was a man she had judicially executed.)

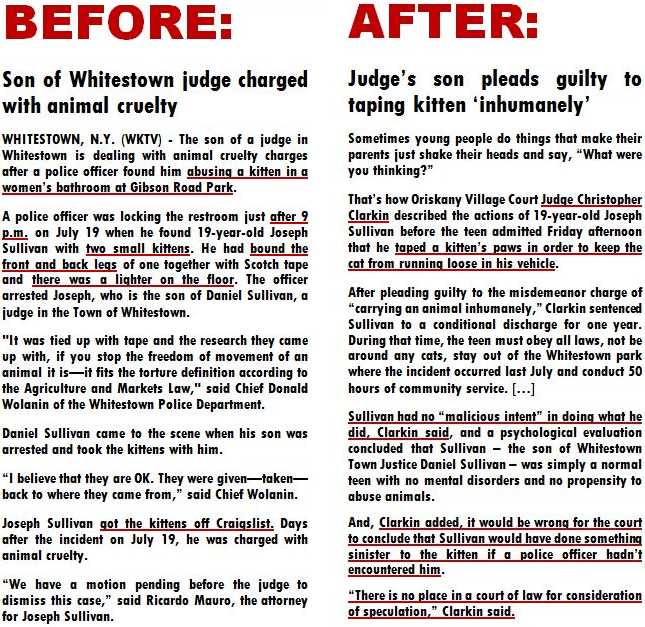

33-year-old Heather Coglaiti went to the Corpus Christi Police Department (CCPD) to report that her on-again-off-again boyfriend, José Calderon, had threatened to hurt her, and had slashed her car tires.

33-year-old Heather Coglaiti went to the Corpus Christi Police Department (CCPD) to report that her on-again-off-again boyfriend, José Calderon, had threatened to hurt her, and had slashed her car tires. This isn’t pettifoggery. Distinctions like this aren’t minor, and they betray how we interpret allegations: We believe they must be true. Objectivity, if not skepticism, though, is the journalist’s brief, not credulity.

This isn’t pettifoggery. Distinctions like this aren’t minor, and they betray how we interpret allegations: We believe they must be true. Objectivity, if not skepticism, though, is the journalist’s brief, not credulity.

Feminist attorney and writer

Feminist attorney and writer  Pols and corporations engage in flimflam to win votes and increase profit shares. Science, too, seeks acclaim and profit, and judicial motives aren’t so different. Judges know what’s expected of them, and they know how to interpret information to satisfy expectations.

Pols and corporations engage in flimflam to win votes and increase profit shares. Science, too, seeks acclaim and profit, and judicial motives aren’t so different. Judges know what’s expected of them, and they know how to interpret information to satisfy expectations. Since judges can rule however they want, and since they know that very well, they don’t even have to lie, per se, just massage the facts a little. It’s all about which facts are emphasized and which facts are suppressed, how select facts are interpreted, and whether “fear” can be reasonably inferred from those interpretations. A restraining order ruling can only be construed as “wrong” if it can be demonstrated that it violated statutory law (or the source that that law must answer to:

Since judges can rule however they want, and since they know that very well, they don’t even have to lie, per se, just massage the facts a little. It’s all about which facts are emphasized and which facts are suppressed, how select facts are interpreted, and whether “fear” can be reasonably inferred from those interpretations. A restraining order ruling can only be construed as “wrong” if it can be demonstrated that it violated statutory law (or the source that that law must answer to:  Feminism’s foot soldiers in the blogosphere and on social media, finally, spread the “good word,” and John and Jane Doe believe what they’re told—unless or until they’re torturously disabused of their illusions. Stories like those you’ll find

Feminism’s foot soldiers in the blogosphere and on social media, finally, spread the “good word,” and John and Jane Doe believe what they’re told—unless or until they’re torturously disabused of their illusions. Stories like those you’ll find

The scales of justice are tipped from the start.

The scales of justice are tipped from the start. The savvy observer will note that suspicion is the motive determiner of liability at all levels. Suspicion informs judicial disposition, subsequent police response to claims of violation, and of course interpretation by third parties, including employers (judges trust accusers, and everyone else trusts judges). Emphatically worthy of remark is that

The savvy observer will note that suspicion is the motive determiner of liability at all levels. Suspicion informs judicial disposition, subsequent police response to claims of violation, and of course interpretation by third parties, including employers (judges trust accusers, and everyone else trusts judges). Emphatically worthy of remark is that  From these concepts, questions immediately present themselves. Are protection orders being utilized in oppressive or unexpected ways? Are the factual scenarios involved similar to what the [legislature] envisioned them to be? Are courts utilizing protection order tools correctly? Are judges issuing ex parte orders that trample upon the rights of innocent people before a hearing is held to determine the validity of specific allegations? Is this area of the law an insufficiently regulated “wild frontier”?

From these concepts, questions immediately present themselves. Are protection orders being utilized in oppressive or unexpected ways? Are the factual scenarios involved similar to what the [legislature] envisioned them to be? Are courts utilizing protection order tools correctly? Are judges issuing ex parte orders that trample upon the rights of innocent people before a hearing is held to determine the validity of specific allegations? Is this area of the law an insufficiently regulated “wild frontier”? While how commonly the process is exploited for ulterior motives is a matter of heated dispute, its availability for abuse is plain. The

While how commonly the process is exploited for ulterior motives is a matter of heated dispute, its availability for abuse is plain. The

The news story the epigraph was excerpted from was prompted by a recent murder in Oregon and explores the impotence of restraining orders, in particular to “stop bullets.” Just as shooting sprees inspire reporters to investigate gun legislation, murder victims who had applied for restraining orders that proved worthless inspire reporters to investigate restraining order policies. The presumption, always, is that the law failed.

The news story the epigraph was excerpted from was prompted by a recent murder in Oregon and explores the impotence of restraining orders, in particular to “stop bullets.” Just as shooting sprees inspire reporters to investigate gun legislation, murder victims who had applied for restraining orders that proved worthless inspire reporters to investigate restraining order policies. The presumption, always, is that the law failed.

“For some people it’s more dangerous [to get a restraining order],” said Kim Larson, director for Marion County District Attorney Victim Assistance Division. “Sometimes it makes people really angry, getting served with a restraining order.”

“For some people it’s more dangerous [to get a restraining order],” said Kim Larson, director for Marion County District Attorney Victim Assistance Division. “Sometimes it makes people really angry, getting served with a restraining order.”