I remarked to a commenter the other day that when I became a vegetarian in the ’80s, I was still a kid, and my family took it as an affront, which was a common reaction then. Today, everyone’s a vegetarian or “tried vegetarianism” or has “thought about becoming a vegetarian.” Other subjects that were outré or taboo in my childhood like atheism, cross-dressing, and depression—they’re no longer stigmatized, either (in the main). Gay people, who were only  whispered about then, can marry in a majority of states. When I was a kid, it was shaming for bra straps or underpants bands to be visible. Today they’re exposed on purpose.

whispered about then, can marry in a majority of states. When I was a kid, it was shaming for bra straps or underpants bands to be visible. Today they’re exposed on purpose.

It’s a brave new world.

While domestic violence is no more comfortable a topic of conversation now than it was then, it’s also hardly hush-hush. When restraining orders were conceived, it was unmentionable, and that was the problem. It was impossible for battered women to reliably get help. They faced alienation from their families and even ridicule from the police if they summoned the courage to ask for it. They were trapped.

Restraining orders cut through all of the red tape and made it possible for battered women to go straight to the courthouse to talk one-on-one with a judge and get immediate relief. The intention, at least, was good.

It’s probable, too, that when restraining orders were enacted way back when, their exploitation was minimal. It wouldn’t have occurred to many people to abuse them, just as it wouldn’t have occurred to lawmakers that anyone would take advantage.

This isn’t 1979. Times have changed and with them social perceptions and ethics. Reporting domestic violence isn’t an act of moral apostasy. It’s widely encouraged.

No one has gone back, however, and reconsidered the justice of a procedure of law that omits all safeguards against misuse. Restraining orders circumvent investigation by police and the vetting of accusations by district attorneys. They allow individuals to prosecute allegations all on their own, trusting that those individuals won’t lie about fear or abuse, despite the fact that there are any number of compelling motives to do so, including greed/profit, spite, victim-playing, revenge, mental illness, personality disorder, bullying, blame-shifting, cover-up, infidelity/adultery, blackmail, coercion, citizenship, stalking, and the mere desire for attention.

Restraining orders laws have steadily accreted even as the original (problematic) blueprint has remained unchanged. Claims no longer need to be of domestic violence (though its legal definition has grown so broad as to be virtually all-inclusive, anyway). They can be of harassment, “stalking,” threat, or just inspiring vague unease.

These aren’t claims that are hard to manufacture, and they don’t have to be proved (and there’s no ascertaining the truth of alleged “feelings” or “beliefs,” anyway, just as there’s no defense against them). Due to decades of feminist lobbying, moreover, judges are predisposed to issue restraining orders on little or no more basis than a petitioner’s saying s/he needs one.

What once upon a time made this a worthy compromise of defendants’ constitutionally guaranteed expectation of due process and equitable treatment under the law no longer does. The anticipation of rejection or ridicule that women who reported domestic violence in the ’70s and ’80s faced from police, and which recommended a workaround like the restraining order, is now anachronistic.

What once upon a time made this a worthy compromise of defendants’ constitutionally guaranteed expectation of due process and equitable treatment under the law no longer does. The anticipation of rejection or ridicule that women who reported domestic violence in the ’70s and ’80s faced from police, and which recommended a workaround like the restraining order, is now anachronistic.

Prevailing reflex from authorities has swiveled 180 degrees. If anything, the conditioned reaction to claims of abuse is their eager investigation; it’s compulsory policy.

Laws that authorize restraining order judges, based exclusively on their discretion, to impose sanctions on defendants like registry in public databases that can permanently foul employment prospects, removal from their homes, and denial of access to their kids and property are out of date. Their license has expired.

Besides material privations, defendants against allegations made in brief trips to the courthouse are subjected to humiliation and abuse that’s lastingly traumatic. Making false claims is a simple matter, and offering damning misrepresentations that don’t even depend on lies is simpler yet.

What shouldn’t be possible happens. A lot. Almost as bad is that we make believe it doesn’t.

Just as it was wrong to avert our eyes from domestic violence 30 years ago, it’s wrong to pretend that attempts to curb it since haven’t fostered new forms of taunting, terrorism, and torment that use the state as their agent.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

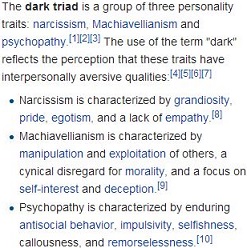

It turns out there’s a sexy phrase for the collective personality traits exhibited by manipulators of this sort: the “

It turns out there’s a sexy phrase for the collective personality traits exhibited by manipulators of this sort: the “

The Dark Triad traits should be associated with preferring casual relationships of one kind or another. Narcissism in particular should be associated with desiring a variety of relationships. Narcissism is the most social of the three, having an approach orientation towards friends (Foster & Trimm, 2008) and an externally validated ‘ego’ (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008). By preferring a range of relationships, narcissists are better suited to reinforce their sense of self. Therefore, although collectively the Dark Triad traits will be correlated with preferring different casual sex relationships, after controlling for the shared variability among the three traits, we expect that narcissism will correlate with preferences for one-night stands and friend[s]-with-benefits.

The Dark Triad traits should be associated with preferring casual relationships of one kind or another. Narcissism in particular should be associated with desiring a variety of relationships. Narcissism is the most social of the three, having an approach orientation towards friends (Foster & Trimm, 2008) and an externally validated ‘ego’ (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008). By preferring a range of relationships, narcissists are better suited to reinforce their sense of self. Therefore, although collectively the Dark Triad traits will be correlated with preferring different casual sex relationships, after controlling for the shared variability among the three traits, we expect that narcissism will correlate with preferences for one-night stands and friend[s]-with-benefits. What we’re talking about in the context of abuse of restraining orders are people who exploit others and then exploit legal process as a convenient means to discard them when they’re through (while whitewashing their own behaviors, procuring additional narcissistic supply in the forms of attention and special treatment, and possibly exacting a measure of revenge if they feel they’ve been criticized or contemned).

What we’re talking about in the context of abuse of restraining orders are people who exploit others and then exploit legal process as a convenient means to discard them when they’re through (while whitewashing their own behaviors, procuring additional narcissistic supply in the forms of attention and special treatment, and possibly exacting a measure of revenge if they feel they’ve been criticized or contemned). I tend to manipulate others to get my way.

I tend to manipulate others to get my way. I came upon a monograph recently that articulates various motives for the commission of fraud, including to bolster an offender’s ego or sense of personal agency, to dominate and/or humiliate his or her victim, to contain a threat to his or her continued goal attainment, or to otherwise exert control over a situation.

I came upon a monograph recently that articulates various motives for the commission of fraud, including to bolster an offender’s ego or sense of personal agency, to dominate and/or humiliate his or her victim, to contain a threat to his or her continued goal attainment, or to otherwise exert control over a situation.