This blog was inspired by firsthand experience with judicial iniquity.

This blog was inspired by firsthand experience with judicial iniquity.

Its author has never been accused of violence, doesn’t sanction violence except in self-defense or the defense of others, and has been a practicing vegetarian since adolescence. I have, what’s more, hazarded my life going to the aid of non-human animals. In one instance, I lost the use of my hand for a year; in another, I had various of my bones fractured or crushed, and that damage is permanent.

Although I’ve never been accused of violence (only its threat: “Will I be attacked?”), I know very well I might have been accused of violence, and I know with absolute certainty that the false accusation could have stuck—and easily—regardless of my ethical scruples and what my commitment to them has cost me.

Who people are, what they stand for, and what they have or haven’t done—these make no difference when they’re falsely fingered by a dedicated accuser who alleges abuse or fear.

This is wrong, categorically wrong, and the only arguments for maintenance of the status quo are ones that favor a particular interest group or political persuasion, which means those arguments contravene the rule of constitutional law.

Justice that isn’t equitable isn’t justice. Arguments for the perpetuation of the same ol’ same ol’, then, are nonstarters. Dogma continues to prevail, however, by distraction: “a majority of rapes go unreported,” “most battered women suffer in silence,” “domestic violence is epidemic” (men have it coming to them). Invocation of social ills that have no bearing on individual cases has determined public policy and conditioned judicial impulse.

Justice that isn’t equitable isn’t justice. Arguments for the perpetuation of the same ol’ same ol’, then, are nonstarters. Dogma continues to prevail, however, by distraction: “a majority of rapes go unreported,” “most battered women suffer in silence,” “domestic violence is epidemic” (men have it coming to them). Invocation of social ills that have no bearing on individual cases has determined public policy and conditioned judicial impulse.

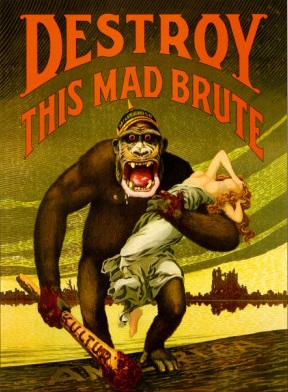

Injustice, no surprise, arouses animosity; injustice that confounds lives, moreover, provokes rage, predictably and justly. This post looks at how that rage is severed from its roots—injustice—and held aloft like a monster’s decapitated head to be scorned and reviled.

I first learned of the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) from a research paper published by Law Professor Kelly Behre this year that equates men’s rights activism with hatemongering. I later heard this position of the SPLC’s reiterated in an NPR piece about the first International Conference on Men’s Issues.

Injustice, it should be noted preliminarily, is of no lesser interest to women than to men. Both men and women are abused by laws and practices purportedly established to protect women, laws and practices that inform civil, criminal, and family court proceedings.

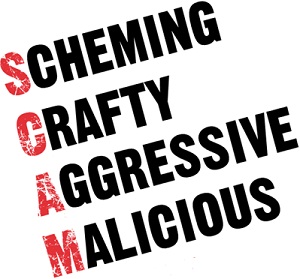

Groups like the SPLC, however, represent opposition to these laws and practices as originating strictly from MRAs, or men’s rights activists, whom they dismiss as senseless haters. This lumping is characteristic of the smoke-and-mirrors tactics favored by those allied to various women’s causes. They limn the divide as being between irrationally irate men and battered women’s advocates (or between “abusers” and “victims”).

They don’t necessarily deny there’s a middle ground; they just ignore it. Consequently, they situate themselves external to it. There are no women’s rights activists (“WRAs”?) who mediate between extremes. They’re one of the extremes.

They don’t necessarily deny there’s a middle ground; they just ignore it. Consequently, they situate themselves external to it. There are no women’s rights activists (“WRAs”?) who mediate between extremes. They’re one of the extremes.

I’m a free agent, and this blog isn’t associated with any group, though the above-mentioned law professor, Dr. Behre, identifies the blog in her paper as authored by an “FRG” (father’s rights group), based on my early on citing the speculative statistic that as many as 80% of restraining orders are said to be “unnecessary” or based on false claims, which may in fact be true even if Dr. Behre finds the estimate unscientific. (Survey statistics cited by women’s advocates and represented as fact are no more ascertainably conclusive; they’re only perceived as more “legitimate.”)

SAVE Services, one of the nonprofits to cite a 2008 West Virginia study from which the roughly 80% or 4-out-of-5 statistic is derived, is characterized by the SPLC and consequently Dr. Behre as being on a par with a “hate group,” like white supremacists. It isn’t, and the accusation is silly, besides nasty. This kind of facile association, though, has proven to be very effective at neutering opposing perspectives, even moderate and disciplined ones. Journalists, the propagators of information, may more readily credit a nonprofit like the SPLC, which identifies itself as a law center and has a longer and more illustrious history, than it may SAVE, which is also a nonprofit. The SPLC’s motto, “Fighting Hate • Teaching Tolerance • Seeking Justice,” could just as aptly be applied to SAVE’s basic endeavor.

On the left is a symbol for the Ku Klux Klan; on the right, the symbol for feminist solidarity. The images have common features, and their juxtaposition suggests the two groups are linked. This little gimmick exemplifies how guilt by association works.

The SPLC’s rhetorical strategy, an m.o. typical of those with the same political orientation, is as follows: (1) scour websites and forums in the “manosphere” for soundbites that include heated denunciations and misogynistic epithets, (2) assemble a catalog of websites and forums that espouse or can be said to sympathize with extremist convictions or positions, and (3) lump all websites and forums speaking to discrimination against men together and collectively label them misogynistic. Thus reports like these: “Misogyny: The Sites” and “Men’s Rights Movement Spreads False Claims about Women.”

Cherry-picked posts, positions, and quotations are highlighted; arguments are desiccated into ideological blurbs punctuated with indelicate words; and all voices are mashed up into a uniform, sinister hiss.

The SPLC’s explicit criticism may not be unwarranted, but coming as it does from a “law center” whose emblem is a set of balanced scales, that criticism is fairly reproached for its carelessness and chauvinism. There are no qualifications to suggest there’s any merit to the complaints that the SPLC criticizes.

The SPLC’s criticism, rather, invites its audience to conclude that complaints of feminist-motivated iniquities in the justice system are merely hate rhetoric, which makes the SPLC’s criticism a PC version of hate rhetoric. The bias is just reversed.

Complaints from the “[mad]manosphere” that are uncivil (or even rabid) aren’t necessarily invalid. The knee-jerk  urge to denounce angry rhetoric betrays how conditioned we’ve been by the prevailing dogma. No one is outraged that people may be falsely implicated as stalkers, batterers, and child molesters in public trials. Nor is anyone outraged that the falsely accused may consequently be forbidden access to their children, jackbooted from their homes, denied employment, and left stranded and stigmatized. This isn’t considered abusive, let alone acknowledged for the social obscenity that it is. “Abusive” is when the falsely implicated who’ve been typified as brutes and sex offenders and who’ve been deprived of everything that meant anything to them complain about it.

urge to denounce angry rhetoric betrays how conditioned we’ve been by the prevailing dogma. No one is outraged that people may be falsely implicated as stalkers, batterers, and child molesters in public trials. Nor is anyone outraged that the falsely accused may consequently be forbidden access to their children, jackbooted from their homes, denied employment, and left stranded and stigmatized. This isn’t considered abusive, let alone acknowledged for the social obscenity that it is. “Abusive” is when the falsely implicated who’ve been typified as brutes and sex offenders and who’ve been deprived of everything that meant anything to them complain about it.

Impolitely. (What would Mrs. Grundy say?)

There’s no question the system is corrupt, and the SPLC doesn’t say it isn’t. It reinforces the corruption by caricaturing the opposition as a horde of frothing woman-haters.

Enter Betty Krachey, a Tennessee woman who knows court corruption intimately. Betty launched a website and e-petition this year to urge her state to prosecute false accusers after being issued an injunction that labeled her a domestic abuser and that she alleges was based on fraud and motivated by spite and greed. Ask her if she’s angry about that, and she’ll probably say you’re damn right. (Her life has nothing to do with whether “most battered women suffer in silence” or “a majority of rapes go unreported,” and those facts in no way justify her being railroaded and menaced by the state.)

I made this website to make people aware of Order of Protections & restraining orders being taken out on innocent people based on false allegations so a vindictive person can gain control with the help of authorities. The false accusers are being allowed to walk away and pay NO consequences for swearing to lies to get these orders! […]

I know that, in my case, the judge didn’t know me. Even though I talked to the magistrate the day BEFORE the order of protection was taken out on me & I told him what I heard [he] had planned for me. They didn’t know that I might have superpowers where I could cause him bodily harm 4 1/2 miles away. SO they had no choice but to protect [him] from me. BUT when they found out this order of protection was based on lies that he swore to, and he used the county in a cunning and vindictive way to get me kicked out of the house – HE SHOULD HAVE HAD TO PAY SOME CONSEQUENCES INSTEAD OF BEING ALLOWED TO WALK AWAY LIKE NOTHING HAPPENED!!!!

Seems like a fair point, and it’s fair points like Betty’s that get talked around and over. There are no legal advocates with the SPLC’s clout looking out for people like Betty; they’re busy making claims like hers seem anomalous, trivial, or crackpot.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*Betty reports she’s been in conference with one of her state’s representatives and has been told she has “a good chance at getting this law changed,” albeit too belatedly to affect her own circumstances. Says Betty, “I still want the law changed to hold false accusers accountable!” Amen to that.

The posited “80%” statistic was seized upon by critics of the restraining order process and bruited broadly on the Internet. I published it myself, and this blog, accordingly, was cited in Prof. Behre’s paper as the product of an “FRG.” It’s actually the product of a single tired and uninspired man who knows that false accusations are made.

The posited “80%” statistic was seized upon by critics of the restraining order process and bruited broadly on the Internet. I published it myself, and this blog, accordingly, was cited in Prof. Behre’s paper as the product of an “FRG.” It’s actually the product of a single tired and uninspired man who knows that false accusations are made.

urge to denounce angry rhetoric betrays how conditioned we’ve been by the prevailing dogma. No one is outraged that people may be falsely implicated as stalkers, batterers, and child molesters in public trials. Nor is anyone outraged that the falsely accused may consequently be forbidden access to their children, jackbooted from their homes, denied employment, and left stranded and stigmatized. This isn’t considered abusive, let alone acknowledged for the social obscenity that it is. “Abusive” is when the falsely implicated who’ve been typified as brutes and sex offenders and who’ve been deprived of everything that meant anything to them complain about it.

urge to denounce angry rhetoric betrays how conditioned we’ve been by the prevailing dogma. No one is outraged that people may be falsely implicated as stalkers, batterers, and child molesters in public trials. Nor is anyone outraged that the falsely accused may consequently be forbidden access to their children, jackbooted from their homes, denied employment, and left stranded and stigmatized. This isn’t considered abusive, let alone acknowledged for the social obscenity that it is. “Abusive” is when the falsely implicated who’ve been typified as brutes and sex offenders and who’ve been deprived of everything that meant anything to them complain about it.

J, a single dad who lives in Texas with his two kids, submitted his story as a comment to the blog in September, prefacing it: “I am writing this to share [it] with the rest of my fellow male victims [who] fall in with the dreaded Crazy.”

J, a single dad who lives in Texas with his two kids, submitted his story as a comment to the blog in September, prefacing it: “I am writing this to share [it] with the rest of my fellow male victims [who] fall in with the dreaded Crazy.” Because it was all complete bullsh*t.

Because it was all complete bullsh*t. He gave me the number of an attorney friend who worked in Little Rock. Next thing I knew, I’m having to fax or email every record I kept that shows my whereabouts on that day: gas receipts, store receipts, etc. I had to get a list of movies that I watched from the video download company we use. Cell phone calls. Text messages. (By the way, they really do monitor those. They can pinpoint your exact location, but you have to send a written request.) All of this to prove I was not there. Once I gave that attorney everything, he told me he would go to court that day and ask for an extension of 60 days. And I would still have to show up in Arkansas. Sh*t!

He gave me the number of an attorney friend who worked in Little Rock. Next thing I knew, I’m having to fax or email every record I kept that shows my whereabouts on that day: gas receipts, store receipts, etc. I had to get a list of movies that I watched from the video download company we use. Cell phone calls. Text messages. (By the way, they really do monitor those. They can pinpoint your exact location, but you have to send a written request.) All of this to prove I was not there. Once I gave that attorney everything, he told me he would go to court that day and ask for an extension of 60 days. And I would still have to show up in Arkansas. Sh*t! The day of the court hearing came. I drove out of state to be there. She actually showed in up in court that day. I suspect she didn’t expect I would show. The judge called out our docket. She sat on one side of the courtroom. My attorney and I sat on the other.

The day of the court hearing came. I drove out of state to be there. She actually showed in up in court that day. I suspect she didn’t expect I would show. The judge called out our docket. She sat on one side of the courtroom. My attorney and I sat on the other. Journalists who recognize the harm of facile or false allegations invariably focus on

Journalists who recognize the harm of facile or false allegations invariably focus on  The implications of restraining orders, what’s more, are generic. There’s no specific charge associated with them. They’re catchalls that categorically imply everything sordid, violent, and creepy. They most urgently suggest stalking, violence, and sexual deviance.

The implications of restraining orders, what’s more, are generic. There’s no specific charge associated with them. They’re catchalls that categorically imply everything sordid, violent, and creepy. They most urgently suggest stalking, violence, and sexual deviance.

People falsely alleged to be abusers on restraining order petitions, particularly men, are treated like brutes, sex offenders, and scum by officers of the court and its staff, besides by authorities and any number of others. Some report their own relatives remain suspicious—often based merely on finger-pointing that’s validated by some judge in a few-minute procedure (and that’s when relatives aren’t the ones making the false allegations).

People falsely alleged to be abusers on restraining order petitions, particularly men, are treated like brutes, sex offenders, and scum by officers of the court and its staff, besides by authorities and any number of others. Some report their own relatives remain suspicious—often based merely on finger-pointing that’s validated by some judge in a few-minute procedure (and that’s when relatives aren’t the ones making the false allegations). So…slanders and libels made by abuse of court process aren’t actionable, slanders and libels that completely sunder the lives of the wrongly accused, who can’t even get them expunged from their records to simply reset their fractured lives to zero.

So…slanders and libels made by abuse of court process aren’t actionable, slanders and libels that completely sunder the lives of the wrongly accused, who can’t even get them expunged from their records to simply reset their fractured lives to zero. Under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), some

Under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), some  All of this is to say that if you issue 60 restraining orders against nonviolent people to every one issued against a violent aggressor, violations of restraining orders resulting in injuries or death will be comparatively few respective to the total number of people “restrained.” It skews the odds in favor of positive perception.

All of this is to say that if you issue 60 restraining orders against nonviolent people to every one issued against a violent aggressor, violations of restraining orders resulting in injuries or death will be comparatively few respective to the total number of people “restrained.” It skews the odds in favor of positive perception.

My son’s girlfriend…filed a domestic abuse CPO [civil protection order] against my son, again telling him that he shouldn’t have left her. He hasn’t been served yet—they keep missing him. She calls my son constantly, stringing him along with the idea that she “might” let it go. He’s taking her out to eat, giving her money, staying the night with her. Hoping that she’ll let it go. All that and yet two hearing dates for him have come and gone with her showing up at both his hearings asking for a continuance because he hasn’t been served.

My son’s girlfriend…filed a domestic abuse CPO [civil protection order] against my son, again telling him that he shouldn’t have left her. He hasn’t been served yet—they keep missing him. She calls my son constantly, stringing him along with the idea that she “might” let it go. He’s taking her out to eat, giving her money, staying the night with her. Hoping that she’ll let it go. All that and yet two hearing dates for him have come and gone with her showing up at both his hearings asking for a continuance because he hasn’t been served. That includes control of the truth. Some cases of blackmail this author has been informed of were instances of the parties accused knowing something about their accusers that their accusers didn’t want to get around (usually criminal activity). When the guilty parties no longer trusted that coercion would ensure that those who had the goods on them would keep quiet, they filed restraining orders against them alleging abuse, which instantly discredited anything the people they accused might disclose about their activities.

That includes control of the truth. Some cases of blackmail this author has been informed of were instances of the parties accused knowing something about their accusers that their accusers didn’t want to get around (usually criminal activity). When the guilty parties no longer trusted that coercion would ensure that those who had the goods on them would keep quiet, they filed restraining orders against them alleging abuse, which instantly discredited anything the people they accused might disclose about their activities. A recent NPR story reports that dozens of students who’ve been accused of rape are suing their universities. They allege they were denied due process and fair treatment by college investigative committees, that is, that they were “railroaded” (and publicly humiliated and reviled). The basis for a suit alleging civil rights violations, then, might also exist (that is, independent of claims of material privation). Certainly most or all restraining order defendants and many domestic violence defendants are “railroaded” and subjected to public shaming and social rejection unjustly.

A recent NPR story reports that dozens of students who’ve been accused of rape are suing their universities. They allege they were denied due process and fair treatment by college investigative committees, that is, that they were “railroaded” (and publicly humiliated and reviled). The basis for a suit alleging civil rights violations, then, might also exist (that is, independent of claims of material privation). Certainly most or all restraining order defendants and many domestic violence defendants are “railroaded” and subjected to public shaming and social rejection unjustly. Undertaking a venture like coordinating a class action is beyond the resources of this writer, but anyone with the gumption to try and transform words into action is welcome to post a notice here.

Undertaking a venture like coordinating a class action is beyond the resources of this writer, but anyone with the gumption to try and transform words into action is welcome to post a notice here.

The scales of justice are tipped from the start.

The scales of justice are tipped from the start. The savvy observer will note that suspicion is the motive determiner of liability at all levels. Suspicion informs judicial disposition, subsequent police response to claims of violation, and of course interpretation by third parties, including employers (judges trust accusers, and everyone else trusts judges). Emphatically worthy of remark is that

The savvy observer will note that suspicion is the motive determiner of liability at all levels. Suspicion informs judicial disposition, subsequent police response to claims of violation, and of course interpretation by third parties, including employers (judges trust accusers, and everyone else trusts judges). Emphatically worthy of remark is that  From these concepts, questions immediately present themselves. Are protection orders being utilized in oppressive or unexpected ways? Are the factual scenarios involved similar to what the [legislature] envisioned them to be? Are courts utilizing protection order tools correctly? Are judges issuing ex parte orders that trample upon the rights of innocent people before a hearing is held to determine the validity of specific allegations? Is this area of the law an insufficiently regulated “wild frontier”?

From these concepts, questions immediately present themselves. Are protection orders being utilized in oppressive or unexpected ways? Are the factual scenarios involved similar to what the [legislature] envisioned them to be? Are courts utilizing protection order tools correctly? Are judges issuing ex parte orders that trample upon the rights of innocent people before a hearing is held to determine the validity of specific allegations? Is this area of the law an insufficiently regulated “wild frontier”? While how commonly the process is exploited for ulterior motives is a matter of heated dispute, its availability for abuse is plain. The

While how commonly the process is exploited for ulterior motives is a matter of heated dispute, its availability for abuse is plain. The

The news story the epigraph was excerpted from was prompted by a recent murder in Oregon and explores the impotence of restraining orders, in particular to “stop bullets.” Just as shooting sprees inspire reporters to investigate gun legislation, murder victims who had applied for restraining orders that proved worthless inspire reporters to investigate restraining order policies. The presumption, always, is that the law failed.

The news story the epigraph was excerpted from was prompted by a recent murder in Oregon and explores the impotence of restraining orders, in particular to “stop bullets.” Just as shooting sprees inspire reporters to investigate gun legislation, murder victims who had applied for restraining orders that proved worthless inspire reporters to investigate restraining order policies. The presumption, always, is that the law failed.

“For some people it’s more dangerous [to get a restraining order],” said Kim Larson, director for Marion County District Attorney Victim Assistance Division. “Sometimes it makes people really angry, getting served with a restraining order.”

“For some people it’s more dangerous [to get a restraining order],” said Kim Larson, director for Marion County District Attorney Victim Assistance Division. “Sometimes it makes people really angry, getting served with a restraining order.”

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

Ironic is that Dr. Behre’s denial of men’s groups’ position that men aren’t treated fairly is itself unfair.

Ironic is that Dr. Behre’s denial of men’s groups’ position that men aren’t treated fairly is itself unfair. A theme that emerges upon consideration of

A theme that emerges upon consideration of  It’s ironic that the focus of those who should be most sensitized to injustice is so narrow. Ironic, moreover, is that “emotional abuse” is frequently a component of state definitions of domestic violence. The state recognizes the harm of emotional violence done in the home but conveniently regards the same conduct as harmless when it uses the state as its instrument.

It’s ironic that the focus of those who should be most sensitized to injustice is so narrow. Ironic, moreover, is that “emotional abuse” is frequently a component of state definitions of domestic violence. The state recognizes the harm of emotional violence done in the home but conveniently regards the same conduct as harmless when it uses the state as its instrument. Here’s yet another irony. Too often the perspectives of those who decry injustices are partisan. Feminists themselves are liable to see only one side.

Here’s yet another irony. Too often the perspectives of those who decry injustices are partisan. Feminists themselves are liable to see only one side. Now consider the motives of false allegations and their certain and potential effects: isolation, termination of employment and impediment to or negation of employability, inaccessibility to children (who are used as leverage), and being forced to live on limited means (while possibly being required under threat of punishment to provide spousal and child support) and perhaps being left with no home to furnish or automobile to drive at all.

Now consider the motives of false allegations and their certain and potential effects: isolation, termination of employment and impediment to or negation of employability, inaccessibility to children (who are used as leverage), and being forced to live on limited means (while possibly being required under threat of punishment to provide spousal and child support) and perhaps being left with no home to furnish or automobile to drive at all. The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin I’ve quoted goes on at some length to detail the difficulties and complexities that unraveling false claims entails for agents of the FBI. Appreciate then how absurd is the state’s faith that a single judge—or a couple of them—can ascertain the truth of civil restraining order allegations by auditing claims in a hearing or hearings arrived at with no prior information, that last mere minutes, and that are furthermore biased by the preconception that the accused is guilty.

The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin I’ve quoted goes on at some length to detail the difficulties and complexities that unraveling false claims entails for agents of the FBI. Appreciate then how absurd is the state’s faith that a single judge—or a couple of them—can ascertain the truth of civil restraining order allegations by auditing claims in a hearing or hearings arrived at with no prior information, that last mere minutes, and that are furthermore biased by the preconception that the accused is guilty. One of the aforementioned teachers was on his way to Nashville to become a songwriter, that is, a creative artist. Any career in the public eye like this one is vulnerable to being compromised or trashed by a scandal that may be based on nothing but cunning lies or a disturbed person’s fantasies spewed impulsively in a window of five or 10 minutes. Besides the obvious impairment that something like this can exert on income prospects, its psychological effects alone can make performance of a job impossible. And nothing kills income prospects more surely than that.

One of the aforementioned teachers was on his way to Nashville to become a songwriter, that is, a creative artist. Any career in the public eye like this one is vulnerable to being compromised or trashed by a scandal that may be based on nothing but cunning lies or a disturbed person’s fantasies spewed impulsively in a window of five or 10 minutes. Besides the obvious impairment that something like this can exert on income prospects, its psychological effects alone can make performance of a job impossible. And nothing kills income prospects more surely than that.

Because restraining orders place no limitations on the actions of their plaintiffs (that is, their applicants), stalkers who successfully petition for restraining orders (which are easily had by fraud) may follow their targets around; call, text, or email them; or show up at their homes or places of work with no fear of rejection or repercussion. In fact, any acts to drive them off may be represented to authorities as violations of those stalkers’ restraining orders. It’s very conceivable that a stalker could even assault his or her victim with complete impunity, representing the act of violence as self-defense (and at least one such victim of assault has been brought to this blog).

Because restraining orders place no limitations on the actions of their plaintiffs (that is, their applicants), stalkers who successfully petition for restraining orders (which are easily had by fraud) may follow their targets around; call, text, or email them; or show up at their homes or places of work with no fear of rejection or repercussion. In fact, any acts to drive them off may be represented to authorities as violations of those stalkers’ restraining orders. It’s very conceivable that a stalker could even assault his or her victim with complete impunity, representing the act of violence as self-defense (and at least one such victim of assault has been brought to this blog).

A principle of law that everyone ensnarled in any sort of legal shenanigan should be aware of is stare decisis. This Latin phrase means “to abide by, or adhere to, decided things” (Black’s Law Dictionary). Law proceeds and “evolves” in accordance with stare decisis.

A principle of law that everyone ensnarled in any sort of legal shenanigan should be aware of is stare decisis. This Latin phrase means “to abide by, or adhere to, decided things” (Black’s Law Dictionary). Law proceeds and “evolves” in accordance with stare decisis.

The

The  Not many years ago, philosopher Harry Frankfurt published a treatise that I was amused to discover called

Not many years ago, philosopher Harry Frankfurt published a treatise that I was amused to discover called  The logical extension of there being no consequences for lying is there being no consequences for lying back. Bigger and better.

The logical extension of there being no consequences for lying is there being no consequences for lying back. Bigger and better.

The 148 search engine terms that appear below—at least one to two dozen of which concern false allegations—are ones that brought readers to this blog between the hours of 12 a.m. and 7:21 p.m. yesterday (and don’t include an additional 49 “unknown search terms”).

The 148 search engine terms that appear below—at least one to two dozen of which concern false allegations—are ones that brought readers to this blog between the hours of 12 a.m. and 7:21 p.m. yesterday (and don’t include an additional 49 “unknown search terms”).

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.