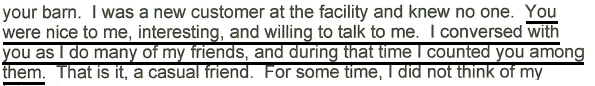

The author of this post recently chipped off a bit more of his dilapidated front teeth on the brim of the coffee mug that’s virtually wedded to his hands. After years of demoralization in the courts, he depends on external energy sources to triumph over inertia and earn a living. The occasion of the damage was his running to give a stylist-in-training a $5 tip for an $8 haircut. This is where one can easily find himself after 12 years of abuse in the court and by the court, whose handsomely paid judges almost invariably excuse themselves for their arrogance, their misperceptions, their shortsightedness, and their professional failings. The exercise of dominance over the lives of others should at the very least demand scrupulous care. This post is inspired by its utter absence.

I occasionally corresponded with UCLA Law Prof. Eugene Volokh in 2016 and 2017 when he consulted with my attorneys in advance of an appeal of numerous unlawful “prior restraints” imposed upon my freedom of speech in 2013 (by a judge who has since been shamed off the bench), and Prof. Volokh was very charitable with his time.

UCLA Law Prof. Eugene Volokh before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee in 2017

I don’t know him well enough to bother him with inquiries about his classroom curricula, though. So I don’t really know the answer to the question posed in this post’s title.

I can, however, surmise.

Prof. Volokh, aided by a gifted law student, Alison Boaz, invested more than a little time in preparing an amicus brief to the Arizona Court of Appeals on my behalf. This is a very big deal. I know, too, that Prof. Volokh is a brilliant jurist, that his arguments to the court were unassailable, and that the court’s disregard for those arguments (which weren’t even mentioned) is a symptom of crap practice that I believe to be pandemic to the point of institutionalization.

(I have no doubt Prof. Volokh would express qualms he had more circumspectly—neutrality comes harder for those who’ve been in the defendant’s seat—but I don’t think he would find much fault with my characterization insofar as it concerns respect for liberties guaranteed by the First Amendment.)

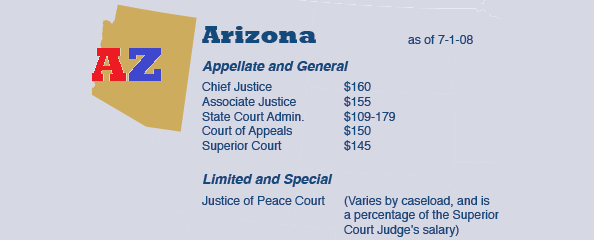

Arizona Chief Justice Scott Bales, who has beautiful teeth, a state that a $160,000 salary and a $130,000/year pension should guarantee he always enjoys

Certainly one way Prof. Volokh could recover on his investment in my case would be to use the ruling returned by Arizona Court of Appeals judges Philip Espinosa, Sean Brearcliffe, and Christopher Staring to show his First Amendment students what they’re up against, namely, recalcitrantly erroneous (i.e., crap) practice by state courts.

In the last post, I shared some informed impressions of some of the judges who’ve weighed in against me over the past 13 years. It’s mostly been crap practice all the way up the ladder, and I know from years of correspondence with others all over the country (and abroad) that my experience is unexceptional.

In 2017, much more knowledgeable after a decade of legal abuse, I succeeded in having two Tucson municipal court judges verbally spanked for abuse of discretion (which roughly translates to judicial abuse of authority), and one of them, Judge Wendy Million, could be said to have literally written the book on protective order law (which will only seem ironic to those who’ve never found themselves in its crosshairs). Judges in this arena can’t even be relied upon to observe statutory requirements let alone comport themselves with anything approaching rigor, impartiality, or politeness.

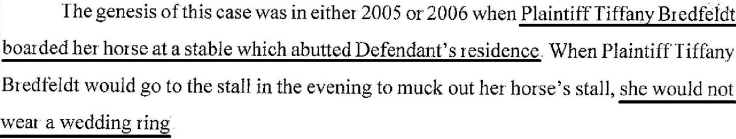

People like Arizona Supreme Court Chief Justice W. Scott Bales, who has backed a proposal to raise judicial salaries by $15,000, shouldn’t be concerned, in this writer’s opinion, about whether judges are getting paid lavishly enough (already $100,000 to $160,000 per plus lifetime pensions that alone exceed the yearly incomes of most of those whose lives they impact and whose labor provides for their salaries).

What people like Scott Bales should be concerned about is whether judges are actually earning anywhere near their purported value.

Copyright © 2019 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*The professor referenced in this post, Eugene Volokh, is a renowned constitutional scholar, and his blog, The Volokh Conspiracy, which is listed by the ABA Journal in its “Blawg 100 Hall of Fame,” appears on the website of The Washington Post. I discerned no hint that the Arizona Court of Appeals judges also referenced in this post had ever heard his name. Prof. Volokh addressed the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee the same year he addressed them.