Since the publication of this post, the “research paper” it responds to has been removed from the Internet.

“I had a false allegation of domestic violence ordered against me on June 19, 2006. It was based on lies, but the local sheriff’s office and state attorney’s office didn’t care that he was a covert, lying narcissist. I doubt they ever heard of the term, in fact. I made the mistake of moving back in with him in September 2008.

“Last year, on July 23, 2013, he, with the help of his conniving sister, literally abandoned me. Left me without transportation and tried to have the electricity cut off. However, the electric company told him it was unlawful to do so. I am disabled, because of him, and have been fighting to get my life, reputation, and sanity restored. It has been over a year, and while life goes on for him, I am still struggling from deep scars of betrayal, lies, and his continued smear campaign against me.

“I thank you for the opportunity to speak out and stand with other true victims of abuse. You see, it isn’t just women who abuse the system, but men, as well.”

—Female e-petition respondent (August 30, 2014)

Contrast this woman’s story with this excerpt from a UC Davis Law Prof. Kelly Behre’s 2014 research paper:

At first glance, the modern fathers’ rights movement and law reform efforts appear progressive, as do the names and rhetoric of the “father’s rights” and “children’s rights” groups advocating for the reforms. They appear a long way removed from the activists who climbed on bridges dressed in superhero costumes or the member martyred by the movement after setting himself on fire on courthouse steps. Their use of civil rights language and appeal to formal gender equality is compelling. But a closer look reveals a social movement increasingly identifying itself as the opposition to the battered women’s movement and intimate partner violence advocates. Beneath a veneer of gender equality language and increased political savviness remains misogynistic undertones and a call to reinforce patriarchy.

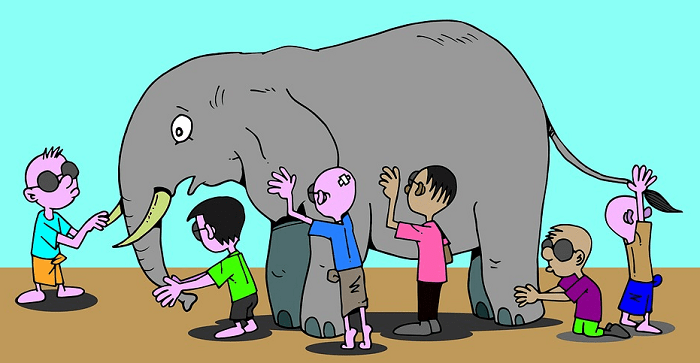

The professor’s perceptions aren’t wrong. Her perspective, however, is limited, because stories like the one in the epigraph fall outside of the boundaries of her focus and awareness (and her interest and allegiance, besides).

What isn’t appreciated by critics of various men’s rights advocacy groups is that these groups’ own criticisms are provoked by legal inequities that are inspired and reinforced by feminist groups and their socially networked loyalists. These feminist groups arrogate to themselves the championship of female causes, among them that of battered women. Feminists are the movers behind the “battered women’s movement.”

What isn’t appreciated by critics of various men’s rights advocacy groups is that these groups’ own criticisms are provoked by legal inequities that are inspired and reinforced by feminist groups and their socially networked loyalists. These feminist groups arrogate to themselves the championship of female causes, among them that of battered women. Feminists are the movers behind the “battered women’s movement.”

Those who criticize unfair laws and policies that purport to protect battered women are not “pro-domestic violence”; they’re anti-injustice, which may well mean they’re anti-feminist, and this can be construed as “opposition to the battered women’s movement.” The opposition, however, is to what the feminist movement has wrought. No one is “for” the battery of women or “against” the protection of battered women.

To put this across in a way a feminist can appreciate, to believe women should have the right to abort a fetus is not the same thing as being “pro-abortion.” No one is “for” abortion, and no one is “for” domestic violence. (“Yay, abortion” is never a sign you’ll see brandished by a picketer at a pro-choice demonstration.)

The Daily Beast op-ed this excerpt is drawn from criticizes a group called “Women Against Feminism” and asserts that feminism is defined by the conviction that “men and women should be social, political, and economic equals.” If this were strictly true, then inequities in judicial process that favor female complainants would be a target of feminism’s censure instead of its vigorous support.

The “clash” the professor constructs in her paper is not, strictly speaking, adversarial, and thinking of it this way is the source of the systemic injustices complained of by the groups she targets. Portraying it as a gender conflict is also archly self-serving, because it represents men’s rights groups as “the enemy.” Drawing an Us vs. Them dichotomy (standard practice in the law) promotes a far more visceral opposition to the plaints of men’s groups than the professor’s 64-page evidentiary survey could ever hope to (“Oh, they’re against us, are they?”).

The basic, rational argument against laws intended to curb violence against women is that they privilege women’s interests and deem women more (credit)worthy than men, which has translated to plaintiffs’ being regarded as more “honest” than defendants, and this accounts for female defendants’ also being victimized by false allegations.

(Women, too, are the victims of false restraining orders and fraudulent accusations of domestic abuse. Consequently, women also lose their jobs, their children, their good names, their health, their social credibility, etc.)

The thesis of the professor’s densely annotated paper (“Digging beneath the Equality Language: The Influence of the Father’s Rights Movement on Intimate Partner Violence Public Policy Debates and Family Law Reform”) is that allegations of legal inequities by men’s groups shouldn’t be preferred to facts, and that only facts should exercise influence on decision-making. This assertion is controverted by the professor’s defense of judicial decisions that may be based on no ascertainable facts whatever—and need not be according to the law. The professor on the one hand denounces finger-pointing from men’s groups and on the other hand defends finger-pointing by complainants of abuse, who are predominately women.

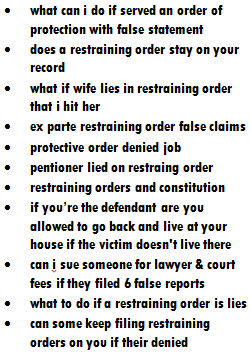

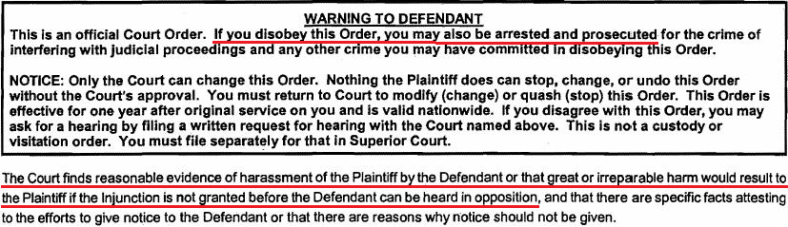

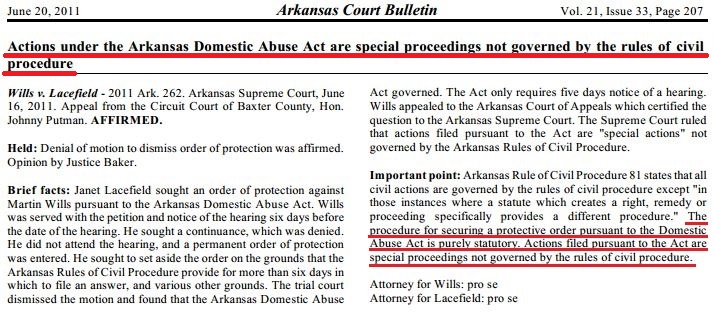

In the arena of law this post concerns, the courts typically follow the dictum that the person pointing the finger is right (and this person is usually female). In other words, the courts judge allegations to be facts. In many instances, what’s more, state law authorizes this formulation. It grants judges the authority “at their discretion” to rule according to accusations and nothing more. Hearsay is fine (and, for example, in California where the professor teaches, the law explicitly says hearsay is fine). The expression of a feeling of danger (genuinely felt or not) suffices as evidence of danger.

The professor’s defense of judicial decision-making based on finger-pointing rather undercuts the credibility of her 64-page polemic against decision-making based on finger-pointing by men’s groups that allege judicial inequities. The professor’s arguments, then, reduce to this position: women’s entitlement to be heeded is greater than men’s.

The problem with critiques of male opposition to domestic violence and restraining order statutes is that those critiques stem from the false presuppositions that (1) the statutes are fair and constitutionally conscientious (they’re not), (2) adjudications based on those statutes are even-handed and just (they’re not), and (3) no one ever exploits those statutes for malicious or otherwise self-serving ends by lying (they do—because they can, for the reasons enumerated above).

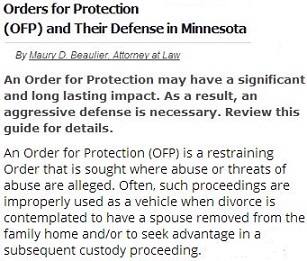

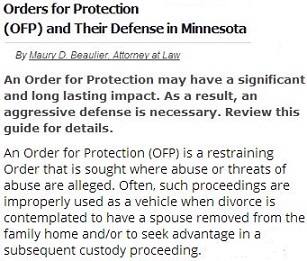

Attorneys acknowledge procedural abuses are common.

Many critiques of men’s, father’s, and children’s rights groups fail to even recognize that motives for lying exist. What presupposition underlies this? That everyone’s an angel? If everyone were an angel, we wouldn’t need laws at all. Or is the presupposition that women are angels? A woman should know better.

A casual Google query will turn up any number of licensed, practicing attorneys all over the country who acknowledge restraining orders and domestic violence laws are abused and offer their services to the falsely accused. Surely the professor wouldn’t allege that these attorneys are fishing for clients who don’t exist—and pretending there’s a problem that doesn’t exist—because they, too, are part of the “anti-battered-women conspiracy.”

The professor’s evidentiary pastiche is at points compelling—it’s only natural that a lot of rage will have been ventilated by people who’ve had their lives torn apart—but her paper’s arguments are finally, exactly like those they criticize, tendentious.

It’s obvious what the professor’s “side” is.

(She accordingly identifies her opposition indiscriminately. For example, the blog you’re right now reading was labeled the product of a father’s rights group or “FRG” in the footnotes of the professor’s paper. This blog is authored by one person only, and he’s not a father. Wronged dads have this writer’s sympathies, but this blog has no affiliation with any groups.)

The professor carefully prefaces her points with phrases like “Researchers have noted,” which gives them the veneer of plausibility but ignores this obvious question: where do the loyalties of those “researchers” lie? The professor cites, for example, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s equation of SAVE Services with a hate group. An attentive survey of SAVE’s reportage, however, would suggest little correspondence. The professor doesn’t quote any of SAVE’s reports; she simply quotes an opposing group’s denunciation of them as being on a par with white supremacist propaganda.

The professor carefully prefaces her points with phrases like “Researchers have noted,” which gives them the veneer of plausibility but ignores this obvious question: where do the loyalties of those “researchers” lie? The professor cites, for example, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s equation of SAVE Services with a hate group. An attentive survey of SAVE’s reportage, however, would suggest little correspondence. The professor doesn’t quote any of SAVE’s reports; she simply quotes an opposing group’s denunciation of them as being on a par with white supremacist propaganda.

(What the professor does quote are some statistics generated by SAVE that she contends are dubious, like estimates of the number and costs of false and frivolous prosecutions. Such estimates must necessarily be speculative, because there are no means of conclusively determining the degree or extent of false allegations. Lies are seldom if ever acknowledged by the courts even if they’re detected. This fact, again, is one that’s corroborated by any number of attorneys who practice in the trenches. Perjury is rarely recognized or punished, so there are no ironclad statistics on its prevalence for advocacy groups to adduce.)

Besides plainly lacking neutrality, insofar as no comparative critical analysis of feminist rhetoric is performed, the professor’s logocentric orientation wants compassion. How much of what she perceives (or at least represents) as bigoted or even crazy would seem all too human if she were to ask herself, for instance, how would I feel if my children were ripped from me by the state in response to lies from someone I trusted, and I were falsely labeled a monster and kicked shoeless to the curb? Were she to ask herself this question and answer it honestly, most of the outraged and inflammatory language she finds offensively “vitriolic” and incendiary would quite suddenly seem understandable, if not sympathetic.

The professor’s approach is instead coolly legalistic, which is exactly the approach that has spawned the heated actions and language she finds objectionable.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

Her statement owns that “false reports [of rape] do really exist.” It also owns that they’re “incredibly damaging.” But it completely discounts the damage to the people falsely accused by those reports.

Her statement owns that “false reports [of rape] do really exist.” It also owns that they’re “incredibly damaging.” But it completely discounts the damage to the people falsely accused by those reports.

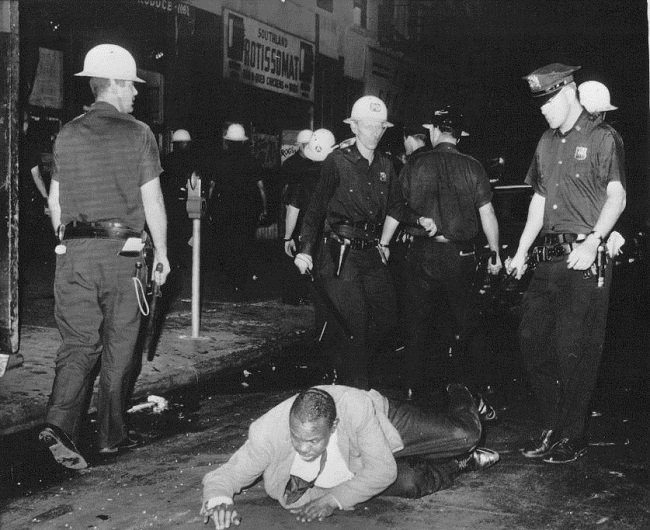

I hope the outraged title of this piece reaches its attention, because the story below exemplifies a modern manifestation of racial bigotry and violence, and it’s one the Southern Poverty Law Center

I hope the outraged title of this piece reaches its attention, because the story below exemplifies a modern manifestation of racial bigotry and violence, and it’s one the Southern Poverty Law Center

Appreciate that the court’s basis for issuing the document capped with the “Warning” pictured above is nothing more than some allegations from the order’s plaintiff, allegations scrawled on a form and typically made orally to a judge in four or five minutes.

Appreciate that the court’s basis for issuing the document capped with the “Warning” pictured above is nothing more than some allegations from the order’s plaintiff, allegations scrawled on a form and typically made orally to a judge in four or five minutes.

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

What isn’t appreciated by critics of various men’s rights advocacy groups is that these groups’ own criticisms are provoked by legal inequities that are inspired and reinforced by feminist groups and their socially networked loyalists. These feminist groups arrogate to themselves the championship of female causes, among them that of battered women. Feminists are the movers behind the “battered women’s movement.”

What isn’t appreciated by critics of various men’s rights advocacy groups is that these groups’ own criticisms are provoked by legal inequities that are inspired and reinforced by feminist groups and their socially networked loyalists. These feminist groups arrogate to themselves the championship of female causes, among them that of battered women. Feminists are the movers behind the “battered women’s movement.”

The professor carefully prefaces her points with phrases like “Researchers have noted,” which gives them the veneer of plausibility but ignores this obvious question: where do the loyalties of those “researchers” lie? The professor cites, for example, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s equation of SAVE Services with a hate group. An attentive survey of SAVE’s reportage, however, would suggest little correspondence. The professor doesn’t quote any of SAVE’s reports; she simply quotes an opposing group’s denunciation of them as being on a par with white supremacist propaganda.

The professor carefully prefaces her points with phrases like “Researchers have noted,” which gives them the veneer of plausibility but ignores this obvious question: where do the loyalties of those “researchers” lie? The professor cites, for example, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s equation of SAVE Services with a hate group. An attentive survey of SAVE’s reportage, however, would suggest little correspondence. The professor doesn’t quote any of SAVE’s reports; she simply quotes an opposing group’s denunciation of them as being on a par with white supremacist propaganda.

Members of the legislative subcommittee referenced in The Courant article reportedly expect to improve their understanding of the flaws inherent in the restraining order process by taking a field trip. They plan “a ‘ride along’ with the representative of the state marshals on the panel…to learn more about how restraining orders are served.”

Members of the legislative subcommittee referenced in The Courant article reportedly expect to improve their understanding of the flaws inherent in the restraining order process by taking a field trip. They plan “a ‘ride along’ with the representative of the state marshals on the panel…to learn more about how restraining orders are served.”

Its introduction, at least, was gripping to read: “At what was billed as the first annual international conference on men’s issues, feminists were ruining everything.” I was keen to hear about how the meeting was disrupted by a mob of angry women swinging truncheons.

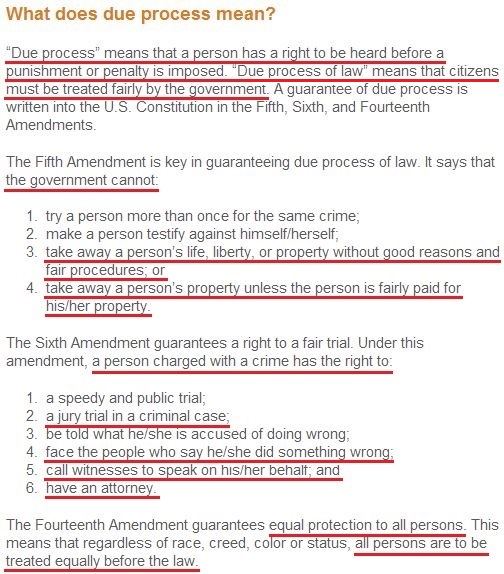

Its introduction, at least, was gripping to read: “At what was billed as the first annual international conference on men’s issues, feminists were ruining everything.” I was keen to hear about how the meeting was disrupted by a mob of angry women swinging truncheons. I’m sympathetic to men’s plaints about legal mockeries that trash lives, including those of children, so I found the MSNBC coverage offensively yellow-tinged in more senses than one, but I’m not what feminists call an MRA or “men’s rights activist.” I don’t think men need any rights the Constitution doesn’t already promise them. What they need is for their government to recognize and honor those rights. The objection to feminism is that it has induced the state to act in wanton violation of citizens’ civil entitlements—not just men’s, but women’s, too.

I’m sympathetic to men’s plaints about legal mockeries that trash lives, including those of children, so I found the MSNBC coverage offensively yellow-tinged in more senses than one, but I’m not what feminists call an MRA or “men’s rights activist.” I don’t think men need any rights the Constitution doesn’t already promise them. What they need is for their government to recognize and honor those rights. The objection to feminism is that it has induced the state to act in wanton violation of citizens’ civil entitlements—not just men’s, but women’s, too. To illustrate, take the

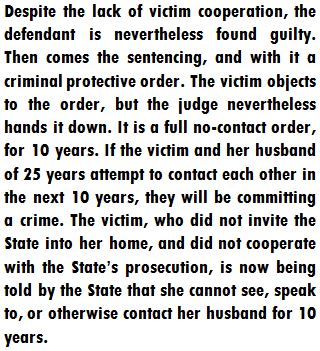

To illustrate, take the  Women I’ve corresponded with in the three years I’ve maintained this blog have reported being stripped of their dignity and good repute, their livelihoods, their homes and possessions, and even their children according to prejudicial laws and court processes that are feminist handiworks. These laws and processes favor plaintiffs, who are typically women, so their prejudices are favored by feminists. Feminists decry inequality when it’s non-advantageous. They’re otherwise cool with it. What’s more, when victims of the cause’s interests are women, those victims are just as indifferently shrugged off—as “casualties of war,” perhaps.

Women I’ve corresponded with in the three years I’ve maintained this blog have reported being stripped of their dignity and good repute, their livelihoods, their homes and possessions, and even their children according to prejudicial laws and court processes that are feminist handiworks. These laws and processes favor plaintiffs, who are typically women, so their prejudices are favored by feminists. Feminists decry inequality when it’s non-advantageous. They’re otherwise cool with it. What’s more, when victims of the cause’s interests are women, those victims are just as indifferently shrugged off—as “casualties of war,” perhaps.

I’ve written before about “

I’ve written before about “

A defendant is deprived of liberty and often property, besides, without compensation and in accordance with manifestly unfair procedures concluded in minutes =

A defendant is deprived of liberty and often property, besides, without compensation and in accordance with manifestly unfair procedures concluded in minutes =  A theme that emerges upon consideration of

A theme that emerges upon consideration of  It’s ironic that the focus of those who should be most sensitized to injustice is so narrow. Ironic, moreover, is that “emotional abuse” is frequently a component of state definitions of domestic violence. The state recognizes the harm of emotional violence done in the home but conveniently regards the same conduct as harmless when it uses the state as its instrument.

It’s ironic that the focus of those who should be most sensitized to injustice is so narrow. Ironic, moreover, is that “emotional abuse” is frequently a component of state definitions of domestic violence. The state recognizes the harm of emotional violence done in the home but conveniently regards the same conduct as harmless when it uses the state as its instrument. Here’s yet another irony. Too often the perspectives of those who decry injustices are partisan. Feminists themselves are liable to see only one side.

Here’s yet another irony. Too often the perspectives of those who decry injustices are partisan. Feminists themselves are liable to see only one side. Now consider the motives of false allegations and their certain and potential effects: isolation, termination of employment and impediment to or negation of employability, inaccessibility to children (who are used as leverage), and being forced to live on limited means (while possibly being required under threat of punishment to provide spousal and child support) and perhaps being left with no home to furnish or automobile to drive at all.

Now consider the motives of false allegations and their certain and potential effects: isolation, termination of employment and impediment to or negation of employability, inaccessibility to children (who are used as leverage), and being forced to live on limited means (while possibly being required under threat of punishment to provide spousal and child support) and perhaps being left with no home to furnish or automobile to drive at all.

Defendants’ being railroaded, of course, is nothing extraordinary. “Emergency” restraining orders may allow respondents only a weekend to prepare before having to appear in court to answer allegations—very possibly false allegations—that have the potential to permanently alter the course of their lives.

Defendants’ being railroaded, of course, is nothing extraordinary. “Emergency” restraining orders may allow respondents only a weekend to prepare before having to appear in court to answer allegations—very possibly false allegations—that have the potential to permanently alter the course of their lives. The answer to these questions is of course known to (besides men) any number of women who’ve been victimized by the restraining order process. They’re not politicians, though. Or members of the ivory-tower club that determines the course of what we call mainstream feminism. They’re just the people who actually know what they’re talking about, because they’ve been broken by the state like butterflies pinned to a board and slowly vivisected with a nickel by a sadistic child.

The answer to these questions is of course known to (besides men) any number of women who’ve been victimized by the restraining order process. They’re not politicians, though. Or members of the ivory-tower club that determines the course of what we call mainstream feminism. They’re just the people who actually know what they’re talking about, because they’ve been broken by the state like butterflies pinned to a board and slowly vivisected with a nickel by a sadistic child. Consider: If someone falsely circulates that you’re a sexual harasser, stalker, and/or violent threat—possibly endangering your employment, to say nothing of savaging you psychologically—you can report that person to the police, seek a restraining order against that person for harassment, and/or sue that person for defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress. If, however, that person first obtains a restraining order against you based on the same false allegations—which is simply a matter of filling out a form and lying to a judge for five or 10 minutes—s/he can then circulate those allegations, which have been officially recognized as legitimate on an order of the court, with impunity. Your credibility, both among colleagues, perhaps, as well as with authorities and the courts, is instantly shot. You may, besides, be subject to police interference based on further false allegations, or even jailed (arrest for violation of a restraining order doesn’t require that the arresting officer actually witness or have incontrovertible proof of anything). And if you are arrested, your credibility is so hopelessly compromised that a false accuser can successfully continue a campaign of harassment indefinitely. Not only that, s/he can expect to do so with the solicitous support and approval of all those who recognize him or her as a “victim” (which may be practically everyone).

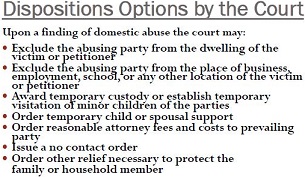

Consider: If someone falsely circulates that you’re a sexual harasser, stalker, and/or violent threat—possibly endangering your employment, to say nothing of savaging you psychologically—you can report that person to the police, seek a restraining order against that person for harassment, and/or sue that person for defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress. If, however, that person first obtains a restraining order against you based on the same false allegations—which is simply a matter of filling out a form and lying to a judge for five or 10 minutes—s/he can then circulate those allegations, which have been officially recognized as legitimate on an order of the court, with impunity. Your credibility, both among colleagues, perhaps, as well as with authorities and the courts, is instantly shot. You may, besides, be subject to police interference based on further false allegations, or even jailed (arrest for violation of a restraining order doesn’t require that the arresting officer actually witness or have incontrovertible proof of anything). And if you are arrested, your credibility is so hopelessly compromised that a false accuser can successfully continue a campaign of harassment indefinitely. Not only that, s/he can expect to do so with the solicitous support and approval of all those who recognize him or her as a “victim” (which may be practically everyone). This means defendants can be denied access to the family pet(s), besides.

This means defendants can be denied access to the family pet(s), besides.

Following Tylenol’s being tampered with in 1981, everything from diced onions to multivitamins requires a safety seal. Naive trust was violated, and legislators responded.

Following Tylenol’s being tampered with in 1981, everything from diced onions to multivitamins requires a safety seal. Naive trust was violated, and legislators responded.