“False Accusations, Distortion Campaigns, and Smear Campaigns can all be used with or without a grain of truth, and have the potential to cause enormous emotional hurt to the victim or even impact [his or her] professional or personal reputation and character.”

—“False Accusations and Distortion Campaigns”

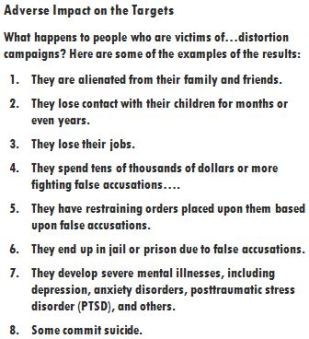

There are several fine explications on the Internet about the smear campaigns of false accusers. Some sketch method and motive generally; some catalog specific damages that ensue when lies are fed to the police and courts.

This survey of “adverse impacts” is credited to lies told by people with borderline personality disorder. Conducting “distortion campaigns” isn’t exclusive to BPDs, however, and the “adverse impacts” are the same, irrespective of campaigners’ particular cognitive kinks.

The valuable role of the police and courts in the prosecution of campaigns to slander, libel, and otherwise bully and defame can’t be overstated. They’re instrumental to a well-orchestrated character assassination.

Lies can be told to anyone, of course, and lies told to anyone can have toxic effects. The right lie told in a workplace, for example, can cost someone a job and impair or imperil a career.

Lies told to police and judges—especially judges—they’re the real wrecking balls, though. False allegations of threat or abuse are handily put over in restraining order or domestic violence procedures, and they endure indefinitely (and embolden accusers to tell further lies, which are that much more persuasive).

Among the motives of false accusation are blame-shifting (cover-up), attention, profit, and revenge (all corroborated by the FBI). Lying, however, may become its own motive, particularly when the target of lies resists. The appetite for malice, once rewarded, may persist long after an initial (possibly impulsive) goal is realized. Smear campaigns that employ legal abuse may go on for years, or indefinitely (usually depending on the stamina of the falsely accused to fight back).

Legitimation of lies by the court both encourages lying and reinforces lies told to others. Consider the implications of this pronouncement: “I had to take out a restraining order on her.” Who’s going to question whether the grounds were real or the testimony was true? Moreover, who’s going to question anything said about the accused once that claim has been made? It’s open season.

In the accuser’s circle, at least—which may be broad and influential—no one may even entertain a doubt, and the falsely accused can’t know who’s been told what and often can’t safely inquire.

Judgments enable smear and distortion campaigners to slander, libel, and otherwise bully with impunity, because their targets have been discredited and left defenseless (judges may even punish them for lawfully exercising their First Amendment rights and effectively gag them). The courts, besides, may rule that specific lies are “true,”  thereby making the slanders and libels impervious to legal relief. Statements that are “true” aren’t defamatory. The man or woman, for instance, who’s wrongly found guilty of domestic violence (and entered into a police database) may be called a domestic abuser completely on the up and up (to friends, family, or neighbors, for example, or to staff at a child’s school).

thereby making the slanders and libels impervious to legal relief. Statements that are “true” aren’t defamatory. The man or woman, for instance, who’s wrongly found guilty of domestic violence (and entered into a police database) may be called a domestic abuser completely on the up and up (to friends, family, or neighbors, for example, or to staff at a child’s school).

Lies become facts that may be shared with anybody and publicly (court rulings are public records). Smear campaigners don’t limit themselves to court-validated lies, either, but it seldom comes back to bite them once a solid foundation has been laid.

Some so-called high-conflict people, the sorts described in the epigraph, conduct their smear or distortion campaigns brazenly and confrontationally. Some poison insidiously, spreading rumors behind closed doors, in conversation and private correspondence. As Dr. Tara Palmatier has remarked, social media also present them with attractive and potent platforms (and many respondents to this blog report being tarred on Facebook or even mobbed, i.e., bullied by multiple parties, including strangers).

Even when false accusers’ claims are outlandish and over the top, like these posted on Facebook by North Carolinian Marty Tackitt-Grist, they’re rarely viewed with suspicion—and almost never if a court ruling (or rulings) in the accusers’ favor can be asserted. The man accused in this comment to ABC’s 20/20 is a retiree with three toy poodles and a passion for aviation who couldn’t “hack” firewood without pain, because his spine is deformed. He is a retired lawyer, but he wasn’t “disbarred” and hasn’t “embezzled” (or, for that matter, “mooned” anyone). He has, however, been jailed consequent to insistent and serial falsehoods from his patently disturbed neighbor…who’s a schoolteacher.

For Crazy, social media websites are an endless source of attention, self-promotion, self-aggrandizement, and a sophisticated weapon. Many narcissists, histrionics, borderlines, and other self-obsessed, abusive personality types use Facebook, Twitter, and the like to run smear campaigns, to make false allegations, to perpetrate parental alienation, and to stalk and harass their targets while simultaneously portraying themselves as the much maligned victim, superwoman, and/or mother of the year.

(A respondent to this blog who’s been relentlessly harried by lies for two years, who’s consequently homeless and penniless, and who’s taken flight to another state, recently reported that a woman who’d offered her aid suddenly and inexplicably defriended her on Facebook and shut her out without a word. Her “friend” had evidently been gotten to.)

(An advocate for legal reform who was falsely accused in court last year by her husband and succeeded in having the allegations against her dismissed reports that he afterwards circulated it around town that she tried to kill him.)

I was falsely accused in 2006 by a woman who had nightly hung around outside of my house for a season. She was married and concealed the fact. Then she lied to conceal the concealment and the behavior that motivated the concealment. She has sustained her fictions (and honed them) for nearly 10 years. People like this build tissues of lies, aptly and commonly called webs.

Their infrastructures are visible, but many strands may not be…and the spinners never stop spinning.

The personality types associated with chronic lying are often represented as serpentine, arachnoid, or vampiric. This ironically feeds into some false accusers’ delusions of potency. Instead of shaming them, it turns them on.

I know from corresponding with many others who’ve endured the same traumas I have that they’ve been induced to do the same thing I did: write to others to defend the truth and hope to gain an advocate to help them unsnarl a skein of falsehoods that propelled them face-first into a slough of despond. (Why people write, if clarification is needed, is because there is no other way to articulate what are often layered and “bizarre” frauds.)

I know with heart-wrenching certainty, also, that these others’ honest and plaintive missives have probably been received with exactly the same suspicion, contempt, and apprehension that mine were. It’s a hideous irony that attempts to dispel false accusations are typically perceived as confirmations of them, including by the court. To complain of being called a stalker, for example, is interpreted as an act of stalking. There’s a kind of awful beauty to the synergy of procedural abuse and lies. (Judges pat bullies on the head and send them home with smiles on their faces.)

Smear campaigns wrap up false accusations authorized by the court with a ribbon and a bow.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

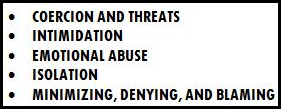

*The name Machiavelli, referenced in the title of this post, is associated with the use of any means necessary to obtain political dominion (i.e., power and control). Psychologists have adapted the name to characterize one aspect of a syzygy of virulent character traits called “The Dark Triad.”

whispered about then, can marry in a majority of states. When I was a kid, it was shaming for bra straps or underpants bands to be visible. Today they’re exposed on purpose.

whispered about then, can marry in a majority of states. When I was a kid, it was shaming for bra straps or underpants bands to be visible. Today they’re exposed on purpose. What once upon a time made this a worthy compromise of defendants’ constitutionally guaranteed expectation of

What once upon a time made this a worthy compromise of defendants’ constitutionally guaranteed expectation of

A scratch, a push, a pinch—which may not even have been real but whose allegation had real enough consequences.

A scratch, a push, a pinch—which may not even have been real but whose allegation had real enough consequences. I’ve written recently about the abuse of restraining orders by fraudulent litigants to punish. What needs observation is that the laws themselves, that is, restraining order and domestic violence statutes, are corrupted by the same motive: to punish. Their motive is not simply to protect (a fact that’s borne out by the prosecution of alleged pinchers).

I’ve written recently about the abuse of restraining orders by fraudulent litigants to punish. What needs observation is that the laws themselves, that is, restraining order and domestic violence statutes, are corrupted by the same motive: to punish. Their motive is not simply to protect (a fact that’s borne out by the prosecution of alleged pinchers). Noteworthy finally is Ms. Malloy’s acknowledgment that false allegations of violence, which are devastating in the emotional oppression, humiliation, and social and professional havoc they wreak on the falsely accused, are used strategically to gain leverage in divorce proceedings.

Noteworthy finally is Ms. Malloy’s acknowledgment that false allegations of violence, which are devastating in the emotional oppression, humiliation, and social and professional havoc they wreak on the falsely accused, are used strategically to gain leverage in divorce proceedings. The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin I’ve quoted goes on at some length to detail the difficulties and complexities that unraveling false claims entails for agents of the FBI. Appreciate then how absurd is the state’s faith that a single judge—or a couple of them—can ascertain the truth of civil restraining order allegations by auditing claims in a hearing or hearings arrived at with no prior information, that last mere minutes, and that are furthermore biased by the preconception that the accused is guilty.

The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin I’ve quoted goes on at some length to detail the difficulties and complexities that unraveling false claims entails for agents of the FBI. Appreciate then how absurd is the state’s faith that a single judge—or a couple of them—can ascertain the truth of civil restraining order allegations by auditing claims in a hearing or hearings arrived at with no prior information, that last mere minutes, and that are furthermore biased by the preconception that the accused is guilty. Her coterie of girlfriends is transposed straight from the halls of high school. They’re less physically favored than the leader of their pack and content to warm themselves in her aura. The adolescent intrigue injects some color into their treadmill lives, and they savor the vicarious thrill of the hunt. The man is a topic of their daily conversation. The women feel young again for a few months, like conspirators in an unconsummated teen crush.

Her coterie of girlfriends is transposed straight from the halls of high school. They’re less physically favored than the leader of their pack and content to warm themselves in her aura. The adolescent intrigue injects some color into their treadmill lives, and they savor the vicarious thrill of the hunt. The man is a topic of their daily conversation. The women feel young again for a few months, like conspirators in an unconsummated teen crush. The life of the man who’d hospitably welcomed the strangers, shaking hands in good faith and doling out mugs of cheer, is trashed: multiple trips to the police precinct to answer false charges and appeals to the court that only invite censure and further abuse. His record, formerly that of an invisible man, becomes hopelessly corrupted. His artistic endeavor, a labor of love that he’d plied himself at for years and on which he’d banked his future joy and financial comfort, is predictably derailed.

The life of the man who’d hospitably welcomed the strangers, shaking hands in good faith and doling out mugs of cheer, is trashed: multiple trips to the police precinct to answer false charges and appeals to the court that only invite censure and further abuse. His record, formerly that of an invisible man, becomes hopelessly corrupted. His artistic endeavor, a labor of love that he’d plied himself at for years and on which he’d banked his future joy and financial comfort, is predictably derailed.