“I hate this world and almost everybody in it. People use each other. I find most of you disgusting. My brothers are disgusting. The people I used to work with are disgusting. You’re shallow, you’re two-faced and hypocritical, you’re judgmental, you cause me more pain than you could ever possibly know. You don’t want me around? Guess what? I don’t want to be around you ugly motherf[—]ers, either. You cause all of your own problems, heap them onto other people, and then blame those people for your problems. You bitch about the amount of pain you’re in, then tell other people to get over their pain.

“I am done with all of you. I am done with your lies and your shitty society, and most of all, I am done kissing your ass.”

—Mrs. Nathan Larson (May 9, 2014)

Virginian Nathan Larson has had a tumultuous year.

He married a woman he met online (April 23, 2014); then she moved out (June 21, 2014) and accused him, among other things, of rape (August 2014 through January 2015); then they divorced; then he learned he was a father when the news reached him that his ex-wife had committed suicide.

The quotation above is from an online post of his former wife’s published between their marriage and their separation. Below is an excerpt from a digital diary entry of hers written when she was a teen (which included a “hit list”):

I hate the students at […]. They are arrogant and foolish. My one dream, my passion is to achieve a machine gun or something and shoot every f[—]er in the school. I want to pump them full of metal, their blood splattered on the tiles. I want to make a massacre that becomes the worst in American history. There are only a few people who I would spare. Everyone else…I would love to see them writhing on the ground in pain, blood oozing out of a million holes in their body.

Nathan’s wife, who was an arguably troubled woman, abruptly terminated their relationship of “75 days total” and then informed him she had miscarried their child. In August 2014, she accused him of rape to the police, but he declined to talk with them and was never charged. In November 2014, she began to accuse him to the courts.

This wasn’t a trial run, either. The accusations brought against Nathan by his wife mirrored charges she had made against a previous partner, also to damning effect.

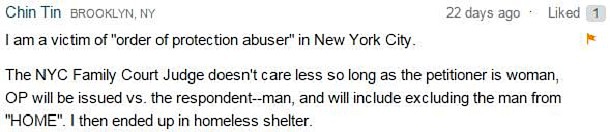

She petitioned three ex parte (temporary) restraining orders before successfully obtaining a permanent order against Nathan in January of this year (by default). Its alleged bases were “domestic abuse, stalking, sexual assault, and physical assault.” The order was petitioned in Colorado, and Nathan would have had to travel a significant distance to be heard in his defense. “Not wanting to invest money and emotional energy in fighting it, and knowing it would be hard for me to successfully contest it, I didn’t show up to the hearing,” he says. He elected to “move on.”

The two were divorced in April 2015, and that seemed to be an end on it.

Two months later, Nathan was told his (then) wife had given birth to a child in February, presumably the one she had told him she had miscarried. This information reached him along with the news that his former wife had killed herself following her commitment for “suicidal depression” and allegedly hearing voices compelling her “to hurt or kill the Child.”

Nathan must now contest a “dependency and neglect petition” in Colorado asserting he’s an unfit parent.

What follows are his reflections on his marriage to a woman who he alleges had untreated borderline personality disorder, on feminism, and on “abuse culture” and its damages.

Nathan Larson (with his new fiancée’s infant cousin)

Having the benefit of distance from the situation and more calmness about it (especially now that she’s dead), I would say that we both made a lot of mistakes during and after the relationship. There are some people who say that it’s a mistake to enter into a relationship with someone with untreated borderline personality, because it simply won’t work, no matter what you do. Unfortunately, once you get into a relationship like that, your sense of reality can get distorted because you’re so in love, and they’re so convincing, and they get so many other people to agree with them, that you too start to believe it if you don’t have enough of an understanding of BPD to realize what’s happening and why.

For example, suppose you used to argue with your BPD partner, and occasionally lost your temper and had to apologize for saying something unkind. Because they’re so sensitive to minor betrayals, they might claim that you horribly emotionally abused and bullied them to get your way, and then tried to be sweet to them and make up, just like in the classic model we’ve been taught of the cycle of abuse. If you’re still thinking this person is the most wonderful person in the world, then logically you might think that you really did emotionally abuse them, because why would such a wonderful person say it if it weren’t true? Plus, they are clearly very upset over how you treated them, and they broke up the relationship over it, and now they’ve told everyone in your circle of friends and family about it, and many of them are telling you they agree that the breakup was your fault because of your emotional abuse.

These are people you respect and trust, and therefore this could not possibly be happening unless you really were abusive!

You start to blame yourself and even tell people, “She left me because I was emotionally abusive” (which of course attracts more criticism, because who would admit that if it weren’t true?). Eventually, you run into someone who hears your account of what was actually said and done, and challenges your interpretation, saying you’re being too hard on yourself, and that this chick is not as great as you seem to think she is. (To which, of course, you may think, “He just doesn’t know and understand her and our deep and beautiful relationship! We were soulmates! What are the chances I will ever find another woman like that? I searched my whole life, and she was the only one like that I’ve ever met who loved and appreciated me so much.”)

If you have good friends, they’ll awaken you to the fact that someone who truly loved you that much would be willing to forgive and come back to you, or at least treat you decently, rather than holding a grudge and trying to make you suffer.

Also, there’s the fact to consider that people with borderline personality disorder idealize and devalue, and they view people as either completely good or completely bad. This means that once they’re faced with the inescapable reality that you’re not perfect, they have to view you as completely evil. They also have to deny any blame at all for the end of the relationship, lest they have to conclude that they too are flawed, which would cause them to view themselves as completely evil. They can’t handle any feelings of guilt; they have to deflect all blame, including the blame for their own emotionality.

Feminists, of course, are not thinking about all this psychology going on behind the scenes.

Feminists, of course, are not thinking about all this psychology going on behind the scenes.

They’re busy calculating whether being skeptical of the claims of someone like that will make the public more likely to be skeptical of the claims of someone with legitimate, serious complaints, and make those victims more reluctant to come forward. So the innocent who was accused gets sacrificed for the greater good.

Some women with borderline personality disorder are attracted to the feminist movement and voraciously read all of their materials about abuse, patriarchy, rape culture, etc. because it helps them view themselves as a helpless victim of powerful sociopaths, and thus deflect blame.

They can find a community of people who will give them the benefit of the doubt by believing their stories, and confirm their interpretation of what happened. Borderlines also sometimes struggle to find a sense of identity, and the feminist movement can provide that as well. Their victimhood actually makes them useful to someone, since it’s a story they can tell and retell to those who need to be persuaded that political change is necessary to stop these abuses. (Feminists, like advocates for most other political movements, would bristle at any suggestion that their ideology attracts mentally ill people, since that would tend to discredit them.)

Yet what the feminist movement can never satisfactorily explain to them is why, despite all this training in recognizing red flags of abusers, and despite all the tools the system has provided for punishing abusers (e.g., restraining orders, prison sentences, etc.), they keep getting “abused” by partner after partner, while many other women seem to have successful, happy relationships.

The only possible answer is that it’s a combination of sociopaths’ finding them particularly attractive for some reason (maybe they sense they’ve been abused and think it’ll be easy to re-victimize them) combined with the fact that the patriarchy is still strong, abused women are still not being believed, and therefore we need to punish abusers more harshly and give the accusers even more benefit of the doubt.

Then, finally, when we have a world where all you need to do to get a man locked away for life is cry rape without any supporting evidence, rational men will finally stop raping. Except, even if such a system were put in place, these insecure women would still feel victimized by their partners, and they would attribute the “abuse” to these guys’ acting impulsively without regard to the certain punishment.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*An excellent explication of procedural abuse by “high-conflict” people (who are associated with personality disorders like BPD) and why court procedure is attractive to them is here.

The ruling was reported Monday on the

The ruling was reported Monday on the

“TRO violation for inadvertent butt calls”

“TRO violation for inadvertent butt calls” Perform a purge, and make sure the firewall has no holes.

Perform a purge, and make sure the firewall has no holes.

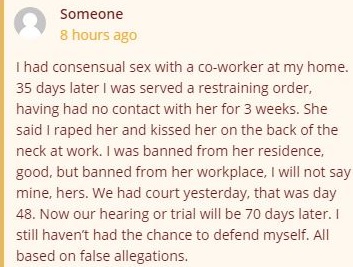

This is how, whether you’re a man or a woman, you can be deemed a rapist without the court’s knowing a thing about you other than your name. (Yes, women, too, are accused of rape in civil court, that is, of having coerced an unwilling partner to have sex.)

This is how, whether you’re a man or a woman, you can be deemed a rapist without the court’s knowing a thing about you other than your name. (Yes, women, too, are accused of rape in civil court, that is, of having coerced an unwilling partner to have sex.)

Feminists, of course, are not thinking about all this psychology going on behind the scenes.

Feminists, of course, are not thinking about all this psychology going on behind the scenes. According to a

According to a

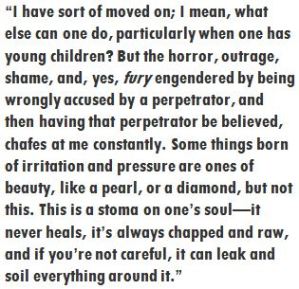

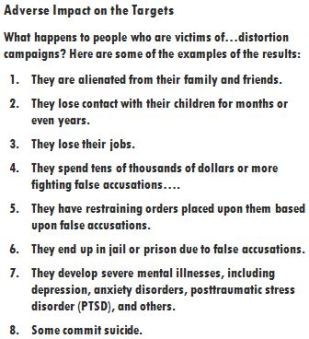

Her statement owns that “false reports [of rape] do really exist.” It also owns that they’re “incredibly damaging.” But it completely discounts the damage to the people falsely accused by those reports.

Her statement owns that “false reports [of rape] do really exist.” It also owns that they’re “incredibly damaging.” But it completely discounts the damage to the people falsely accused by those reports.

I am a little league, travel ball, and high school umpire. I umpire because I love the game and to make some additional money on the side. I have been umpiring baseball for close to 25 years without any incident whatsoever, and most reviews of my performance have been complimentary.

I am a little league, travel ball, and high school umpire. I umpire because I love the game and to make some additional money on the side. I have been umpiring baseball for close to 25 years without any incident whatsoever, and most reviews of my performance have been complimentary. parenting and considers herself an expert in child-rearing. I had even caught her entering my house and administering medication to my daughter without our consent, which I firmly put a stop to.

parenting and considers herself an expert in child-rearing. I had even caught her entering my house and administering medication to my daughter without our consent, which I firmly put a stop to. Well, because there was no good reason for my sister-in-law to be upset, and because the umpire company needed me to cover the game, I did. There was no issue with the game, and I received many compliments afterwards. I ended up working another one of my nephew’s games a couple of weeks later, again with no issues. The next week, I got a call from my umpire assignor reporting that my sister-in-law filed a complaint with the league saying her son was “uncomfortable” with my working behind the plate.

Well, because there was no good reason for my sister-in-law to be upset, and because the umpire company needed me to cover the game, I did. There was no issue with the game, and I received many compliments afterwards. I ended up working another one of my nephew’s games a couple of weeks later, again with no issues. The next week, I got a call from my umpire assignor reporting that my sister-in-law filed a complaint with the league saying her son was “uncomfortable” with my working behind the plate. After about a two-hour hearing, the judge ruled against me. He stated that because my wife informed me that her younger sister had told her to keep me away from her kid that I was put on notice…yet persisted in showing up at the fields to work. Never mind that I was told two months after their conversation (my wife didn’t tell me right away because she thought it was just her sister acting crazy). The judge then went on to say that a mother had the right to determine who got to be around her kids and didn’t need a good reason.

After about a two-hour hearing, the judge ruled against me. He stated that because my wife informed me that her younger sister had told her to keep me away from her kid that I was put on notice…yet persisted in showing up at the fields to work. Never mind that I was told two months after their conversation (my wife didn’t tell me right away because she thought it was just her sister acting crazy). The judge then went on to say that a mother had the right to determine who got to be around her kids and didn’t need a good reason. We have filed a motion for a new trial with compelling evidence. It was denied by the same judge. We have also filed a motion to modify the order to allow me to attend my daughter’s school events since I am her primary caregiver while my wife is at work (I own my own business), and this too was denied, because the judge thought it would be too hard for the school and the police to enforce.

We have filed a motion for a new trial with compelling evidence. It was denied by the same judge. We have also filed a motion to modify the order to allow me to attend my daughter’s school events since I am her primary caregiver while my wife is at work (I own my own business), and this too was denied, because the judge thought it would be too hard for the school and the police to enforce.

A: Right (

A: Right ( I grudgingly constructed a page this week on Facebook, which confirmed to me two things I already knew: (1) I really hate Facebook, and (2) women are more socially networked than men.

I grudgingly constructed a page this week on Facebook, which confirmed to me two things I already knew: (1) I really hate Facebook, and (2) women are more socially networked than men. Notice that 200 to 400 times greater interest in bonding with people concerned with women’s rights has been shown than interest in bonding with people concerned with men’s rights. That’s a lot…A LOT a lot.

Notice that 200 to 400 times greater interest in bonding with people concerned with women’s rights has been shown than interest in bonding with people concerned with men’s rights. That’s a lot…A LOT a lot.