“It was late summer when we met, on a patio jutting out onto the Pacific. The night was still warm as I sipped my Gewürztraminer and asked him about his exciting career. His articulate responses drew me in, and I breathed back nerves and adrenaline with the ocean air as we continued this perfect first date.”

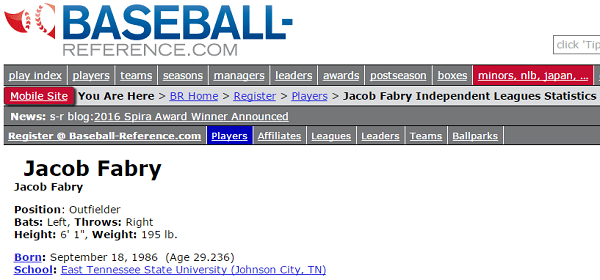

—Marlisse Silver Sweeney, The Atlantic (2014)

I don’t know about you, but she lost me at Gewürztraminer.

Ms. Sweeney goes on to report that her dream date afterwards propositioned her with an “almost full frontal—via Snapchat,” despite which she agreed to meet up with him again…because who could resist?

Two minutes in, or perhaps when he asked me if I wanted to leave the restaurant and go take a bath together, I realized we were looking for different things.

One of those sudden epiphanies, I guess.

A few days later, he sent me a Snapchat video. It was a close-up shot of him masturbating for ten seconds.

It’s a toss-up as to who in the story is the bigger exhibitionist, the man it describes…or the woman narrating it.

Color me cloistered, but this kind of thing never happens to me—and I don’t think I’m alone. Ms. Sweeney’s piece would apparently have us believe encounters like this occur all the time. The subhead to her story asserts: “Over a third of women report being stalked or threatened on the Internet.”

That’s one in three.

A couple of preliminary observations:

- I don’t know anyone out of their teens who would know how to receive a “Snapchat” video (apparently the would-be paramours had exchanged various media contacts after their “romantic” evening).

- If over a third of women report being “stalked or threatened on the Internet,” we should consider what that says about female sensitivity, and they should consider joining a book club.

Ms. Sweeney’s article concerns what’s called “cyber-stalking,” and writers who use this word concern me.

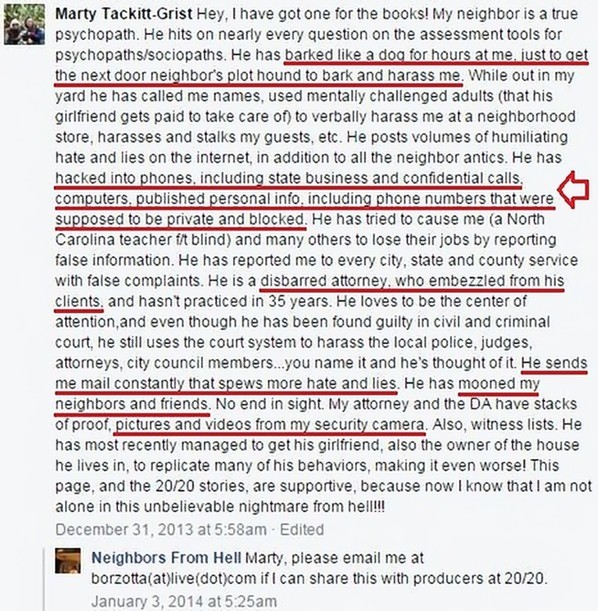

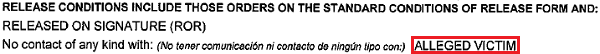

At its most basic legal definition, “cyber-stalking is a repeated course of conduct that’s aimed at a person designed to cause emotional distress and fear of physical harm,” said Danielle Citron, a professor at the University of Maryland’s Francis King Carey School of Law. Citron is an expert in the area of cyber-stalking, and recently published the book called Hate Crimes in Cyberspace. Citron told me that cyber-stalking can include threats of violence (often sexual), spreading lies asserted as facts (like a person has herpes, a criminal record, or is a sexual predator), posting sensitive information online (whether that’s nude or compromising photos or social security numbers), and technological attacks (falsely shutting down a person’s social-media account). “Often, it’s a perfect storm of all these things,” she said.

This definition isn’t bad, and what it describes is, but this definition doesn’t say a lot more than it does. What it doesn’t say, for example, is that online statements ABOUT people, even critical or “invasive” ones, aren’t necessarily untrue but can still be represented as “cyber-stalking” thanks to the influence of stories like Ms. Sweeney’s and books like Dr. Citron’s. Opinions and truthful statements, even if “unwanted speech,” are nevertheless protected speech.

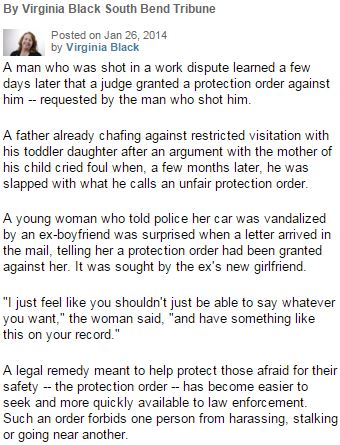

The irony is that alarmist reports like Ms. Sweeney’s have both emboldened and empowered flagrant abuses of legal procedures meant to curb harm. Harm, for those who’ve forgotten, inflicts pain; it doesn’t merely wound pride or arouse distaste.

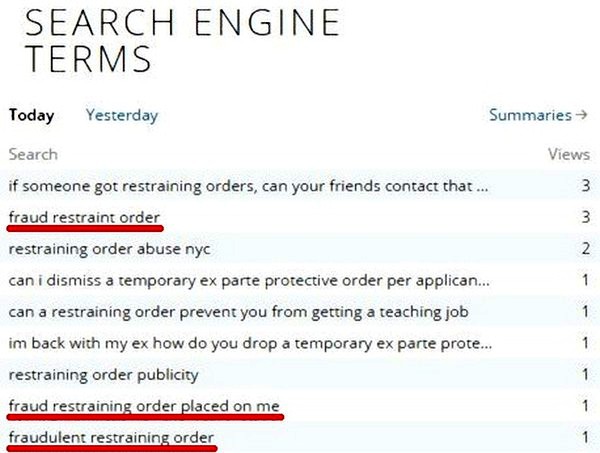

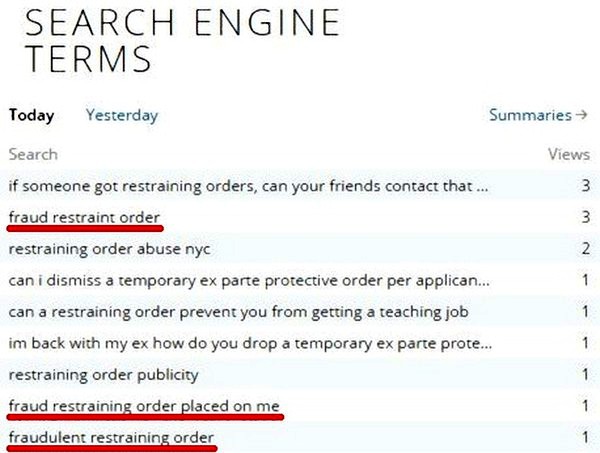

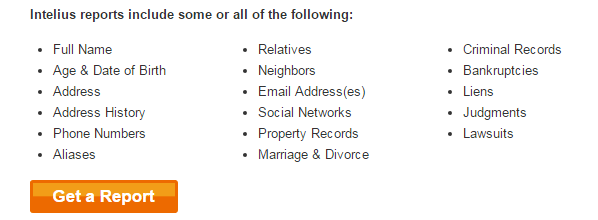

“[S]preading lies asserted as facts” is exactly what false accusation is. It’s often the reason legal procedures are exploited, and there are no consequences for that. Typically there are no forms or redress, either. People lie on restraining order petitions, in domestic violence proceedings, and to Child Protective Services. The motives for lying, what’s more, are not hard to imagine and don’t require painstaking elucidation, least of all to intelligent people possessed of the kind of imagination that could produce the sentence quoted at the top of this post (apropos of which a couple of the motives for lying are attention-seeking and self-aggrandizement.)

The absence of accountability and modes of redress within the system means people who are misrepresented to it (and who may accordingly be driven to the brink of desperation) are left with no recourse but to tell their stories. Even this may be denied them if a false accuser alleges speech ABOUT him or her is “cyber-stalking,” because a bottom-tier judge is likely to agree, again thanks to stories like the one criticized here. (Consider the case assayed in the previous post.)

While the Ms. Sweeneys of the world are sipping Gewürztraminers by the seaside, there are people living (possibly out of their cars) in constant apprehension or under the unremitting weight of false onuses. Ms. Sweeney cites a case of a woman’s committing suicide after being “cyber-stalked.” The casualties of false accusation are far more numerous, and false accusations, unlike computers, can’t be turned off or tuned out (they’re consuming).

Feminist abdication of responsibility isn’t just careless; it’s corrosive. If you don’t want to get “penis pictures” in your inbox, don’t date men who send them. If you don’t want people badmouthing you on the Internet, follow the granola bumper sticker maxim and “Be Nice.” If you’re among the “third” of women who believe they’re being “stalked,” unplug (and consider doing something productive or enriching with your time instead of living a vicarious life on Twitbook). If you don’t want naked pictures of yourself on the Internet, don’t pose for them—or upload them to the Internet if you do.

People who assume public presences also assume the attendant risks. What’s shocking is that this even needs to be said.

Critical speech ABOUT a person should not automatically be assumed to be unjust. Saying unkind things about vicious people is the definition of just. It’s also constitutionally protected. Having the right to say your piece is the point of the First Amendment, which defends the concept of accountability against the concept of kumbaya.

The Internet has broadened the frontier of what’s covered by the First Amendment. No longer are critics limited to voicing disapproval with handbills and signboards staked in their front yards. Their use of online media to accomplish the same end is no less protected, however.

The person liberal writers reflexively want to label “bully,” “harasser,” or “stalker” may be the actual victim of bullying, harassment, or stalking.

A reminder to those writers: Don’t blame the victim.

Copyright © 2016 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

Similarly, if a woman accusing a man of stalking looks like someone whose best opportunity for attention is accusing a man of stalking, a little ding! should sound in the minds of the people vetting the claim. There are women who are “to die for” (hubba-hubba), and there are women who are “to croak for” (ribbet). How about some discernment?

Similarly, if a woman accusing a man of stalking looks like someone whose best opportunity for attention is accusing a man of stalking, a little ding! should sound in the minds of the people vetting the claim. There are women who are “to die for” (hubba-hubba), and there are women who are “to croak for” (ribbet). How about some discernment?