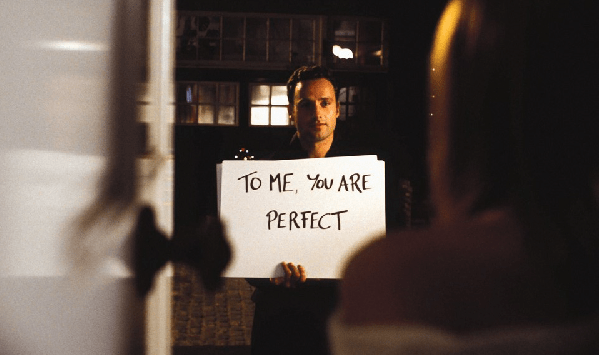

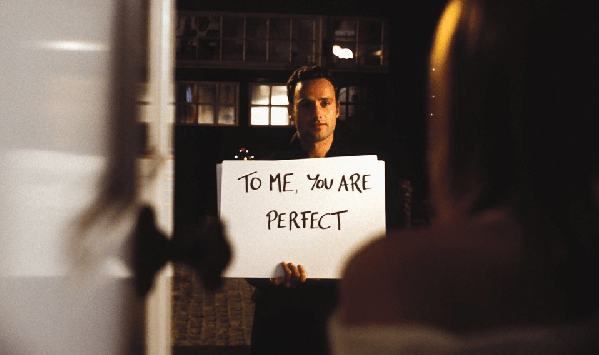

“One card says: ‘To me, you are perfect.’ Another says: ‘My wasted heart will love you ‘til you look like this [insert image of a time-ravaged skeleton].’ Juliet laughs. My reaction would be to slam the door and get a restraining order. What is Mark implying here?”

—Maitri Mehta, Bustle.com

Answer: What Mark is “implying” (with gentle, anguished humor) is that he will love Juliet “till the end of time” (“till the wells run dry, and every mountain disappears”) despite knowing his love can’t be requited. Mark silently confesses his feelings, to ease Juliet’s mind as much as his own, and then he walks away with no expectations at all. His is an act of apology and “closure” that could only be read as a tender gesture by people possessed of a soul.

(Ms. Mehta, exhibiting the undisciplined critical faculty characteristic of feminists and other judges, feels a picture of a skeleton authorizes her to infer that Mark intends to turn Juliet into one. Context is invisible to those who only see in monochrome.)

According to the Ms. Mehtas of the world, one of the great romantic figures of literature, Cyrano de Bergerac, would be a “stalker,” because he“serially” wooed his lady love beneath her balcony while masquerading as someone else.

(“And that nose and rapier! What was Cyrano implying there?”)

It doesn’t matter that neither Roxane nor Juliet was afraid. What matters is that they Damn Well Should Have Been.

By feminists’ lights, I’m a stalker, too, and I can’t imagine any romantic who wouldn’t be. I wrote love notes to a classmate in first grade even after she told me not to. With crayon hearts on them. I suppose the feminist interpretation of what my purple construction paper cards “implied” would be that I wanted to eat the girl’s organs.

They’re to be pitied, I guess, these women who never obsessively wrote a boy’s name in their notebooks as a girl or tittered with their friends about a schoolmate while spying on him (again) from behind a bank of lockers—and I would pity instead of scorn them if I didn’t know firsthand how perniciously influential their twisted perspectives are.

I was invited to visit some older friends on Christmas to watch Love Actually with them. That’s the movie the quotation above refers to. They’re in their 70s, and this is a holiday ritual of theirs.

The Mark-and-Juliet scene is a poignant one, and only an emotionally disturbed mind could construe it otherwise.

Ms. Mehta says this scene represents for her “a level of creepy that shakes me to my core, and every time she runs after him and kisses him in the street, I cringe.” (The phrase “every time” betrays Ms. Mehta has nevertheless watched the movie over and over.)

Sentiments like hers are what make me cringe. (Ms. Mehta’s name says her family is from India, where people still squat in the dirt because indoor plumbing isn’t universal. People starve there, too.)

I introduce Ms. Mehta’s remarks in this context (a blog about restraining orders), because they’re not exclusive to her. They echo social science produced by a post-doc fellow at Michigan U, Julia Lippman, who performed a study that concludes romantic comedies “mak[e] stalking behaviors seem like a normal part of romance.” It’s titled, “The Effects of Media Portrayals of Persistent Pursuit on Beliefs about Stalking.”

This “work” isn’t discounted, either. Google it. Dr. Lippman has her own website.

In a write-up about the study in The Atlantic, Julie Beck quotes the National Institute of Justice’s definition of stalking as “a course of conduct directed at a specific person that involves repeated (two or more occasions) visual or physical proximity, nonconsensual communication, or verbal, written, or implied threats, or a combination thereof, that would cause a reasonable person fear.”

You’ll find this definition inscribed in many states’ criminal statutes.

Observe that the language is so tortured with qualifying phrases beginning with “or” that the “fear” component seems optional—and feminists more than suggest it is.

To judge from Ms. Mehta’s response to a scene in a romantic comedy, the “reasonable person” restriction in the definition of “stalking”…is entirely superfluous.

Copyright © 2016 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*A comment from a female respondent submitted three days ago: “I too am a victim, then became a whistle blower/informant exposing my perps, then victimized again with six false stalking petitions…. Three were granted and all were dismissed, including one where we made case law!” The respondent calls herself “Warrior Lady in Florida.” When I was a kid, that’s what feminists were: warrior ladies. Today, they’re distinguished for cringing.

The ruling was reported Monday on the

The ruling was reported Monday on the