Above, Prof. Eugene Volokh argues before the Georgia Supreme Court in Chan v. Ellis (2014). Prof. Volokh teaches free speech law, religious freedom law, church-state relations law, a First Amendment Amicus Brief Clinic, and tort law at UCLA School of Law.

“If you post on social media about your life, is that going against a restraining order if you don’t mention the petitioner’s name?”

—Search term that led someone here last week

As UCLA Law Prof. Eugene Volokh has doggedly emphasized in his blog, The Volokh Conspiracy (formerly hosted by The Washington Post), the answer to this question is no, it isn’t going against a restraining order if you write ABOUT the order, ABOUT the person who petitioned it, or ABOUT the impact it’s had on your life. Your right to express your opinions and talk about your life to the public at large is protected by the First Amendment.

A person may legitimately be prohibited by a judge from communicating something TO someone (by phone or text, say, or by email or in a letter, or in person), but a judge “can’t order someone to just stop saying anything about a person.”

The citizen’s right to talk about him- or herself, about someone else (including by name), or about anything (excepting state secrets) is sacrosanct. It’s protected by the First Amendment, and a trial judge has no rightful authority to contradict the Constitution.

Note that the key phrase here is rightful authority. A judge can act in ignorance, and s/he can even act in willful contravention of the law.

Why Eugene Volokh’s is a name to know is that Prof. Volokh has endeavored to make the distinction between speech that may be prohibited and speech that may not be prohibited everyday knowledge. He’s done that by writing in a medium accessible to everybody, a blog, rather than exclusively in law journals, as well as by framing in simplest terms the difference between speech that may be censored and speech that may not be.

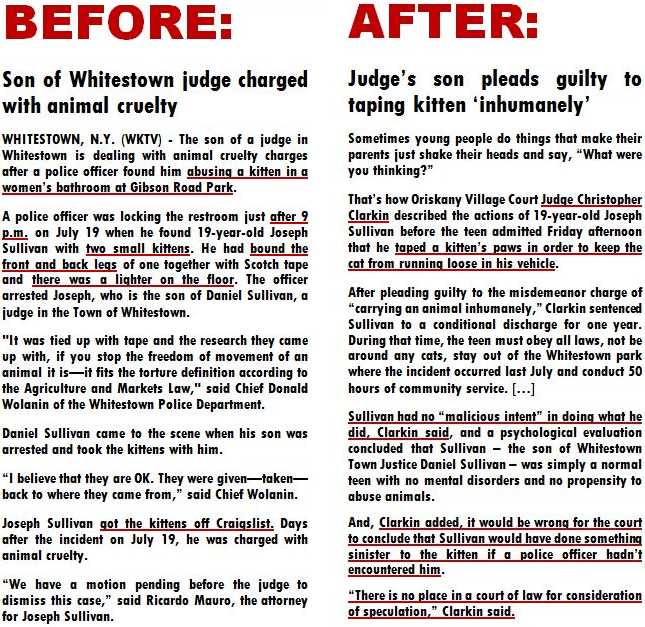

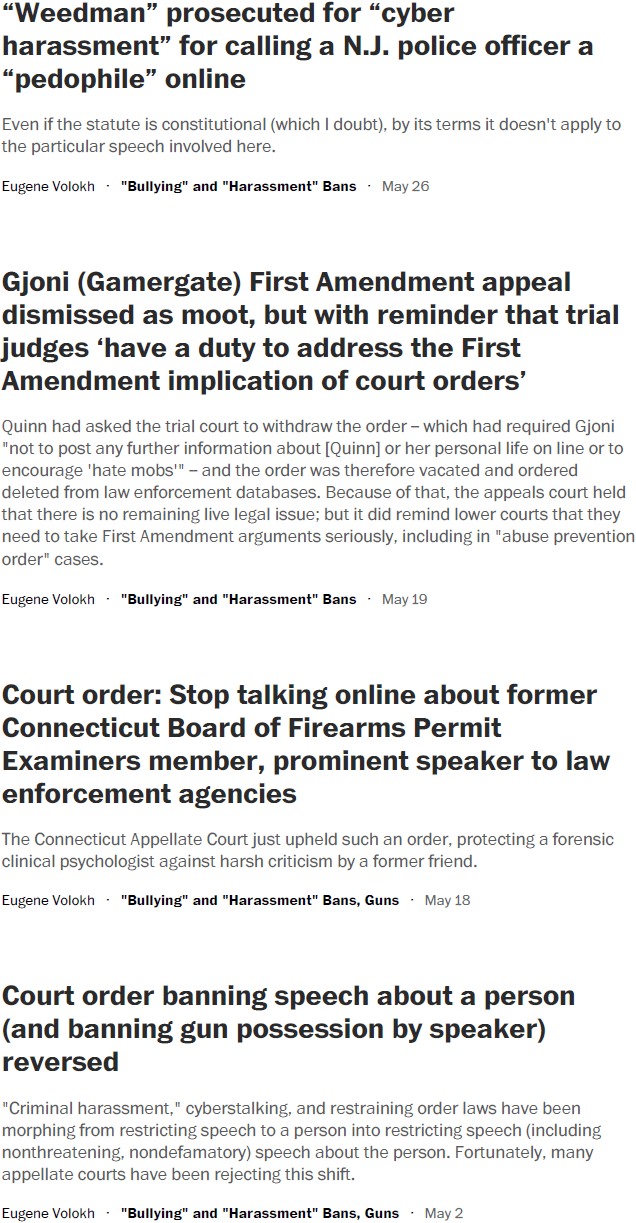

He’s building steam, too. These posts are from last month alone:

It’s important to observe that nothing in the restraining order arena is hard-and-fast, because judges can rule however they want. When what they do clashes with the law, an abused defendant’s only recourse is to appeal, and the intrepid writer should be prepared to do that…right on up the ladder. (S/he should also know that s/he has the right to request reimbursement for lost time, for costs, etc.)

A blogger wrote last month to report that an ex-boyfriend’s claims of “domestic violence” were laughed out of court and that the motive for the accusations was that she had criticized him in a blog. The guy went back to the courthouse a couple of weeks later, petitioned another order from a different judge, and that one stuck. His abuse of process had recent precedent, and it didn’t matter.

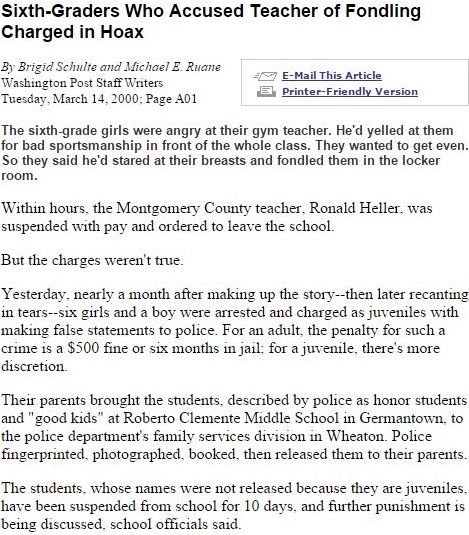

Such manipulations of the justice system by false complainants and spongy decision-making by judges owe to 20 years of mainstream feminist rhetoric decrying “epidemic” violence. Judges have been trained according to tailored social science and had it impressed upon them what their priorities should be. Too, they’ve traditionally been given no cause to second-guess themselves.

Eugene Volokh is changing that.

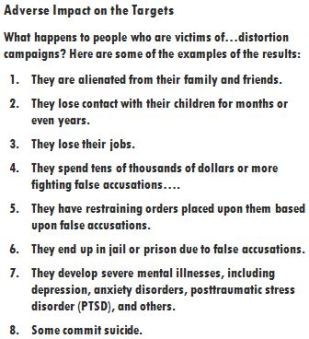

A steady stream of cogent arguments against the due process violations (and statutory and conditioned inequities) that make the restraining order process contemptible has been voiced by influential critics since the ’90s…to little effect.

Rather than appeals to reason and social conscience, what may finally turn the tide against a corrupt procedure of law is an indirect attack on its legitimacy. Once it’s commonly known that speech about its victims’ experiences cannot lawfully be squelched, and that both the issuers of orders and their petitioners can be exposed, warts and all, what has been an unaccountable process no longer will be. Shadowy (and shady) proceedings that have enjoyed invisibility will have to tolerate the glare of spotlights.

And bullies don’t like reading about themselves.

Copyright © 2016 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*The motives of a goodly proportion of false complainants are to cause pain and have the party they’ve injured gagged. Restraining orders are the perfect tool for this. But what people say on public record (e.g., in a courtroom) is public property. It’s supposed to be the opposite of hush-hush.

I grudgingly constructed a page this week on Facebook, which confirmed to me two things I already knew: (1) I really hate Facebook, and (2) women are more socially networked than men.

I grudgingly constructed a page this week on Facebook, which confirmed to me two things I already knew: (1) I really hate Facebook, and (2) women are more socially networked than men. Notice that 200 to 400 times greater interest in bonding with people concerned with women’s rights has been shown than interest in bonding with people concerned with men’s rights. That’s a lot…A LOT a lot.

Notice that 200 to 400 times greater interest in bonding with people concerned with women’s rights has been shown than interest in bonding with people concerned with men’s rights. That’s a lot…A LOT a lot.

Pols and corporations engage in flimflam to win votes and increase profit shares. Science, too, seeks acclaim and profit, and judicial motives aren’t so different. Judges know what’s expected of them, and they know how to interpret information to satisfy expectations.

Pols and corporations engage in flimflam to win votes and increase profit shares. Science, too, seeks acclaim and profit, and judicial motives aren’t so different. Judges know what’s expected of them, and they know how to interpret information to satisfy expectations. Since judges can rule however they want, and since they know that very well, they don’t even have to lie, per se, just massage the facts a little. It’s all about which facts are emphasized and which facts are suppressed, how select facts are interpreted, and whether “fear” can be reasonably inferred from those interpretations. A restraining order ruling can only be construed as “wrong” if it can be demonstrated that it violated statutory law (or the source that that law must answer to:

Since judges can rule however they want, and since they know that very well, they don’t even have to lie, per se, just massage the facts a little. It’s all about which facts are emphasized and which facts are suppressed, how select facts are interpreted, and whether “fear” can be reasonably inferred from those interpretations. A restraining order ruling can only be construed as “wrong” if it can be demonstrated that it violated statutory law (or the source that that law must answer to:  Feminism’s foot soldiers in the blogosphere and on social media, finally, spread the “good word,” and John and Jane Doe believe what they’re told—unless or until they’re torturously disabused of their illusions. Stories like those you’ll find

Feminism’s foot soldiers in the blogosphere and on social media, finally, spread the “good word,” and John and Jane Doe believe what they’re told—unless or until they’re torturously disabused of their illusions. Stories like those you’ll find