My previous post concerned distortion, specifically by those with narcissistic personality disorder (one of a number of personality disorders that may lead a person to make false allegations, that is, to distort the truth). Restraining order fraud, whether committed by pathological liars or the garden variety, tends to go over smashingly, because judges’ biases (perceptual and otherwise) predispose them to credit and reward fraud.

Below is a list of cognitive distortions (categories of automatic thinking) drawn from Wikipedia interspersed with commentaries. Many if not most of these cognitive distortions are applicable to restraining order decisions and clarify how it is that slanted, hyperbolic, or false allegations made through the medium of the restraining order stick.

Below is a list of cognitive distortions (categories of automatic thinking) drawn from Wikipedia interspersed with commentaries. Many if not most of these cognitive distortions are applicable to restraining order decisions and clarify how it is that slanted, hyperbolic, or false allegations made through the medium of the restraining order stick.

(Cognitive distortion or automatic thinking is pathological thinking associated with neurological disorders.)

All-or-nothing thinking: seeing things in black or white as opposed to shades of gray; thinking in terms of false dilemmas. Splitting involves using terms like “always,” “every,” or “never” when this is neither true, nor equivalent to the truth.

Restraining order rulings are categorical. They don’t acknowledge gradations of culpability, nor do they address the veracity of individual allegations. Rulings are “yea” or “nay,” with “yea” predominating. That some, most, or all of what a plaintiff alleges is unsubstantiated makes no difference, nor does it matter if some or most of his or her allegations are contradictory or patently false. Restraining order adjudications are zero-sum games.

Overgeneralization: making hasty generalizations from insufficient experiences and evidence.

Restraining order applications are approved upon five or 10 minutes of “deliberation” and in the absence of any controverting testimony from their defendants (who aren’t invited to the party). All rulings, therefore, are arguably hasty and necessarily generic. (They may in fact be mechanical: a groundless restraining order was famously approved against celebrity talk show host David Letterman because its applicant filled out the form correctly.)

Filtering: focusing entirely on negative elements of a situation, to the exclusion of the positive. Also, the brain’s tendency to filter out information which does not conform to already held beliefs.

Judicial attention is only paid to negative representations, and plaintiffs’ representations are likely to be exclusively negative. Judges seek reasons to approve restraining orders sooner than reasons to reject them, and it’s assumed that plaintiffs’ allegations are valid. In fact, it’s commonly mandated that judges presume plaintiffs are telling the truth (despite their possibly having any of several motives to lie).

Disqualifying the positive: discounting positive events.

Mitigating circumstances are typically discounted. Plaintiffs’ perceptions, which may be hysterical, pathologically influenced, or falsely represented, are usually all judges concern themselves with, even after defendants have been given the “opportunity” to contest allegations against them (which opportunity may be afforded no more than 10 to 20 minutes).

Jumping to conclusions: reaching preliminary conclusions (usually negative) from little (if any) evidence.

All conclusions in restraining order cases are jumped-to conclusions. Allegations, which are leveled during brief interviews and against defendants whom judges may never meet, need be no more substantial than “I’m afraid” (a representation that’s easily falsified).

Magnification and minimization: giving proportionally greater weight to a perceived failure, weakness or threat, or lesser weight to a perceived success, strength or opportunity, so the weight differs from that assigned to the event or thing by others.

Judicial inclination is toward approving/upholding restraining orders. In keeping with this imperative, a judge will pick and choose allegations or facts that can be emphatically represented as weighty or “preponderant.” (One recent respondent to this blog shared that a fraudulent restraining order against him was upheld because the judge perceived that he “appear[ed] to be controlling” and that the plaintiff “seem[ed] to have some apprehension toward [him].” While superficial, airy-fairy standards like “appeared” and “seemed” would carry little weight in a criminal procedure, they’re sufficient qualifications to satisfy and sustain a civil restraining order judgment, which is based on judicial discretion.)

Emotional reasoning: presuming that negative feelings expose the true nature of things, and experiencing reality as a reflection of emotionally linked thoughts. Thinking something is true, solely based on a feeling.

The grounds for most restraining orders are alleged emotional states (“I’m afraid,” for example), which judges typically presume to be both honestly represented and valid (that is, reality-based). Consequently, judges may treat defendants cruelly according with their own emotional motives.

Should statements: doing, or expecting others to do, what they morally should or ought to do irrespective of the particular case the person is faced with. This involves conforming strenuously to ethical categorical imperatives which, by definition, “always apply,” or to hypothetical imperatives which apply in that general type of case. Albert Ellis termed this “musturbation.”

All restraining order judgments are essentially generic (and all restraining order defendants are correspondingly treated generically = badly). Particulars are discounted and may well be ignored.

Labeling and mislabeling: a more severe type of overgeneralization; attributing a person’s actions to their character instead of some accidental attribute. Rather than assuming the behavior to be accidental or extrinsic, the person assigns a label to someone or something that implies the character of that person or thing. Mislabeling involves describing an event with language that has a strong connotation of a person’s evaluation of the event.

The basis of a defendant’s “guilt” may be nothing more than a plaintiff’s misperception.

Personalization: attributing personal responsibility, including the resulting praise or blame, for events over which a person has no control.

The restraining order process is entirely geared toward assigning blame to its defendant, regardless of the actual circumstances, of which a judge has only a plaintiff’s representation, a representation that may be false or fantastical. A circumstance a defendant may be blamed for that s/he has no control over, for example, is a plaintiff’s being neurotic, delusional, or deranged.

Blaming: the opposite of personalization; holding other people responsible for the harm they cause, and especially for their intentional or negligent infliction of emotional distress on us.

- Fallacy of change: Relying on social control to obtain cooperative actions from another person.

- Always being right: Prioritizing self-interest over the feelings of another person.

This last category of automatic thinking sums up a judge’s role and m.o. to a T. And, at least in the latter instance (“Always being right”), shouldn’t. If, to the contrary, judges always assumed their first impressions and impulses were wrong, any number of miscarriages of justice might be avoided.

Copyright © 2013 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

The idea that even one perpetrator of violence should escape justice is horrible, but the idea that anyone who’s alleged to have committed a violent offense or act of deviancy should be assumed guilty is far worse.

The idea that even one perpetrator of violence should escape justice is horrible, but the idea that anyone who’s alleged to have committed a violent offense or act of deviancy should be assumed guilty is far worse.

No topic defies neutral qualification, and since Wikipedia’s own “Restraining order” page recognizes that restraining orders are widely claimed to be misused, and since restraining orders are furthermore issued against millions of people every year across the globe, restraining order abuse can hardly be dismissed as a trivial topic or one unworthy of attention and elucidation. That’s its being disregarded owes to avoidance of a sensitive subject is a more credible explanation.

No topic defies neutral qualification, and since Wikipedia’s own “Restraining order” page recognizes that restraining orders are widely claimed to be misused, and since restraining orders are furthermore issued against millions of people every year across the globe, restraining order abuse can hardly be dismissed as a trivial topic or one unworthy of attention and elucidation. That’s its being disregarded owes to avoidance of a sensitive subject is a more credible explanation.

Victims of false allegations made on restraining orders may be labeled “stalker,” “batterer,” “sicko,” “sexual harasser,” “child-abuser,” “whore,” or even “rapist”—publicly and permanently—by accusers whose sole motive is to brutalize. And agents of these victims’ own government(s) arbitrarily authorize this bullying and may baselessly and basely participate in it, compounding the injury exponentially.

Victims of false allegations made on restraining orders may be labeled “stalker,” “batterer,” “sicko,” “sexual harasser,” “child-abuser,” “whore,” or even “rapist”—publicly and permanently—by accusers whose sole motive is to brutalize. And agents of these victims’ own government(s) arbitrarily authorize this bullying and may baselessly and basely participate in it, compounding the injury exponentially.

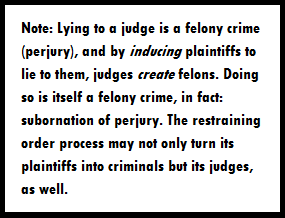

Many restraining order recipients are brought to this site wondering how to recover damages for false allegations and the torments and losses that result from them. Not only is perjury (lying to the court) never prosecuted; it’s never explicitly acknowledged. The question arises whether false accusers

Many restraining order recipients are brought to this site wondering how to recover damages for false allegations and the torments and losses that result from them. Not only is perjury (lying to the court) never prosecuted; it’s never explicitly acknowledged. The question arises whether false accusers

Civil injunctions aren’t warnings; they’re orders of the court. If violated, even by the express invitation of their plaintiffs—and if the search terms that bring people to this blog are any indication (and they are), this happens more than anyone cares to acknowledge—the consequences to their defendants may be extreme, including months of incarceration, loss of employment, and all of the possible ramifications (physical, psychological, and material) that attend both. Police won’t inquire whether renewed relations between a plaintiff and a defendant were consensual, nor will they care. They’ll just slap the cuffs on, and the situation isn’t one that an ill-informed plaintiff can simply “clear up.” It’s out of his or her hands. It’s sufficient, furthermore, for an officer to reasonably believe a violation has occurred. No report by the plaintiff is required to authorize an arrest.

Civil injunctions aren’t warnings; they’re orders of the court. If violated, even by the express invitation of their plaintiffs—and if the search terms that bring people to this blog are any indication (and they are), this happens more than anyone cares to acknowledge—the consequences to their defendants may be extreme, including months of incarceration, loss of employment, and all of the possible ramifications (physical, psychological, and material) that attend both. Police won’t inquire whether renewed relations between a plaintiff and a defendant were consensual, nor will they care. They’ll just slap the cuffs on, and the situation isn’t one that an ill-informed plaintiff can simply “clear up.” It’s out of his or her hands. It’s sufficient, furthermore, for an officer to reasonably believe a violation has occurred. No report by the plaintiff is required to authorize an arrest. I’m 100 blog posts old…and feel it.

I’m 100 blog posts old…and feel it. I was contacted by a woman a few months ago who was issued a false restraining order sought by a vindictive and parasitic man who meant to use the system to hurt her. She happened to be out of town and timed her return to coincide with the order’s expiration for non-service. (Restraining orders must be served within a specified period, for example, 45 days. If this term elapses, the restraining order is voided, and its applicant must return to the courthouse and start the process over.) This cagey woman actually called the police, explained the situation, and inquired how long they had to serve her. She didn’t hide from them; she simply remained unavailable for that period. Upon her return, she applied for a restraining order against her false accuser…and got it.

I was contacted by a woman a few months ago who was issued a false restraining order sought by a vindictive and parasitic man who meant to use the system to hurt her. She happened to be out of town and timed her return to coincide with the order’s expiration for non-service. (Restraining orders must be served within a specified period, for example, 45 days. If this term elapses, the restraining order is voided, and its applicant must return to the courthouse and start the process over.) This cagey woman actually called the police, explained the situation, and inquired how long they had to serve her. She didn’t hide from them; she simply remained unavailable for that period. Upon her return, she applied for a restraining order against her false accuser…and got it.

Those who profit politically and monetarily by the misery inflicted through court processes that are easily abused by the “morally unencumbered” love all this conflict and misdirected rage, which only ensure that these corrupt processes continue to thrive.

Those who profit politically and monetarily by the misery inflicted through court processes that are easily abused by the “morally unencumbered” love all this conflict and misdirected rage, which only ensure that these corrupt processes continue to thrive.

Playing the victim is a very potent form of passive aggression when the audience includes authorities and judges. Validation from these audience members is particularly gratifying to the egos of frauds, and both the police and judges have been trained to respond gallantly to the appeals of “damsels in distress.”

Playing the victim is a very potent form of passive aggression when the audience includes authorities and judges. Validation from these audience members is particularly gratifying to the egos of frauds, and both the police and judges have been trained to respond gallantly to the appeals of “damsels in distress.” I’ll answer for you: No, he doesn’t sound crazy or dangerous. Next question (this is how critical thinking works): If he’s telling it true, how is something like this possible?

I’ll answer for you: No, he doesn’t sound crazy or dangerous. Next question (this is how critical thinking works): If he’s telling it true, how is something like this possible? One of the aforementioned teachers was on his way to Nashville to become a songwriter, that is, a creative artist. Any career in the public eye like this one is vulnerable to being compromised or trashed by a scandal that may be based on nothing but cunning lies or a disturbed person’s fantasies spewed impulsively in a window of five or 10 minutes. Besides the obvious impairment that something like this can exert on income prospects, its psychological effects alone can make performance of a job impossible. And nothing kills income prospects more surely than that.

One of the aforementioned teachers was on his way to Nashville to become a songwriter, that is, a creative artist. Any career in the public eye like this one is vulnerable to being compromised or trashed by a scandal that may be based on nothing but cunning lies or a disturbed person’s fantasies spewed impulsively in a window of five or 10 minutes. Besides the obvious impairment that something like this can exert on income prospects, its psychological effects alone can make performance of a job impossible. And nothing kills income prospects more surely than that. The show is set in 1964, so we can pretend that we’re looking back at a distant, degenerate period in the past when heinous violations could occur right under everyone’s nose, and no one would lift a finger to intervene. The same political games masked as “conversion therapies” are indulged today, of course, only their abuses are subtler and directed at the psyche instead of being committed with canes, electrodes, tongs, and scalpels.

The show is set in 1964, so we can pretend that we’re looking back at a distant, degenerate period in the past when heinous violations could occur right under everyone’s nose, and no one would lift a finger to intervene. The same political games masked as “conversion therapies” are indulged today, of course, only their abuses are subtler and directed at the psyche instead of being committed with canes, electrodes, tongs, and scalpels. Like the characters in American Horror Story: Asylum, many individuals who’ve visited this blog and I have told our tales repeatedly to figures in authority who’ve discounted or disregarded them, preferring instead to administer the mandated treatment.

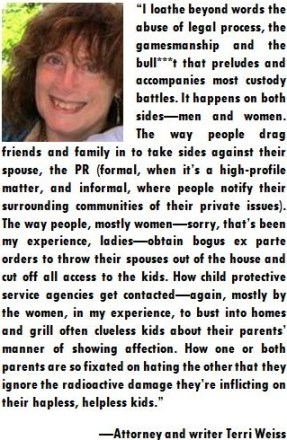

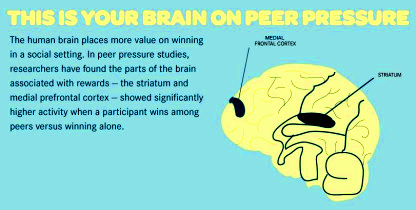

Like the characters in American Horror Story: Asylum, many individuals who’ve visited this blog and I have told our tales repeatedly to figures in authority who’ve discounted or disregarded them, preferring instead to administer the mandated treatment. Although men regularly abuse the restraining order process, it’s more likely that tag-team offensives will be by women against men. Women may be goaded on by their parents or siblings, by authorities, by girlfriends, or by dogmatic women’s advocates. The expression of discontentment with a partner may be regarded as grounds enough for exploiting the system to gain a dominant position. These women may feel obligated to follow through to appease peer or social expectations. Or they may feel pumped up enough by peer or social support to follow through on a spiteful impulse. Girlfriends’ responding sympathetically, whether to claims of quarreling with a spouse or boy- or girlfriend or to claims that are clearly hysterical or even preposterous, is both a natural female inclination and one that may steel a false or frivolous complainant’s resolve.

Although men regularly abuse the restraining order process, it’s more likely that tag-team offensives will be by women against men. Women may be goaded on by their parents or siblings, by authorities, by girlfriends, or by dogmatic women’s advocates. The expression of discontentment with a partner may be regarded as grounds enough for exploiting the system to gain a dominant position. These women may feel obligated to follow through to appease peer or social expectations. Or they may feel pumped up enough by peer or social support to follow through on a spiteful impulse. Girlfriends’ responding sympathetically, whether to claims of quarreling with a spouse or boy- or girlfriend or to claims that are clearly hysterical or even preposterous, is both a natural female inclination and one that may steel a false or frivolous complainant’s resolve.

“If we did prosecute perjurers, there’d be no resources left for putting dangerous people behind bars…so we’ll prosecute the people perjurers falsely accuse of being dangerous”—as analysis of most of the arguments made in defense of domestic violence and restraining order policies reveals, the reasoning is circular and smells foul. It’s in fact unreasoned “reasoning” that’s really just something to say to distract attention from unflattering truths that don’t win elections, federal grants, popular esteem, or political favor. So entrenched are these policies and so megalithic (and lucrative) that rhetoric like this actually passes for satisfactory when it’s used by someone in a crisp suit with a crisper title.

“If we did prosecute perjurers, there’d be no resources left for putting dangerous people behind bars…so we’ll prosecute the people perjurers falsely accuse of being dangerous”—as analysis of most of the arguments made in defense of domestic violence and restraining order policies reveals, the reasoning is circular and smells foul. It’s in fact unreasoned “reasoning” that’s really just something to say to distract attention from unflattering truths that don’t win elections, federal grants, popular esteem, or political favor. So entrenched are these policies and so megalithic (and lucrative) that rhetoric like this actually passes for satisfactory when it’s used by someone in a crisp suit with a crisper title. The restraining order process has become a perfunctory routine verging on a skit, a scripted pas de deux between a judge and a complainant. Exposure of the iniquity of this procedural farce hardly requires commentary.

The restraining order process has become a perfunctory routine verging on a skit, a scripted pas de deux between a judge and a complainant. Exposure of the iniquity of this procedural farce hardly requires commentary. In case you were wondering—and since you’re here, you probably were—there is no gaining relief from false allegations on a civil restraining order. Repetition for emphasis: There is no gaining relief from false allegations on a civil restraining order. Why? Because as far as the court’s concerned, there are no such things.

In case you were wondering—and since you’re here, you probably were—there is no gaining relief from false allegations on a civil restraining order. Repetition for emphasis: There is no gaining relief from false allegations on a civil restraining order. Why? Because as far as the court’s concerned, there are no such things. Many of the respondents to this blog are the victims of collisions like this. Some anomalous moral zero latched onto them, duped them, exploited them, even assaulted them and then turned the table and misrepresented them to the police and the courts as a stalker, harasser, or brute to compound the injury. Maybe for kicks, maybe for “payback,” maybe to cover his or her tread marks, maybe to get fresh attention at his or her victim’s expense, or maybe for no motive a normal mind can hope to accurately interpret.

Many of the respondents to this blog are the victims of collisions like this. Some anomalous moral zero latched onto them, duped them, exploited them, even assaulted them and then turned the table and misrepresented them to the police and the courts as a stalker, harasser, or brute to compound the injury. Maybe for kicks, maybe for “payback,” maybe to cover his or her tread marks, maybe to get fresh attention at his or her victim’s expense, or maybe for no motive a normal mind can hope to accurately interpret. I came upon a monograph recently that articulates various motives for the commission of fraud, including to bolster an offender’s ego or sense of personal agency, to dominate and/or humiliate his or her victim, to contain a threat to his or her continued goal attainment, or to otherwise exert control over a situation.

I came upon a monograph recently that articulates various motives for the commission of fraud, including to bolster an offender’s ego or sense of personal agency, to dominate and/or humiliate his or her victim, to contain a threat to his or her continued goal attainment, or to otherwise exert control over a situation. Below is a list of cognitive distortions (categories of automatic thinking) drawn from

Below is a list of cognitive distortions (categories of automatic thinking) drawn from  The outrage of

The outrage of  Consider whether you don’t think this kind of scenario is more likely to exert a detrimental influence on a child’s development (and whether Jesus wouldn’t have thought so):

Consider whether you don’t think this kind of scenario is more likely to exert a detrimental influence on a child’s development (and whether Jesus wouldn’t have thought so):

Because restraining orders place no limitations on the actions of their plaintiffs (that is, their applicants), stalkers who successfully petition for restraining orders (which are easily had by fraud) may follow their targets around; call, text, or email them; or show up at their homes or places of work with no fear of rejection or repercussion. In fact, any acts to drive them off may be represented to authorities as violations of those stalkers’ restraining orders. It’s very conceivable that a stalker could even assault his or her victim with complete impunity, representing the act of violence as self-defense (and at least one such victim of assault has been brought to this blog).

Because restraining orders place no limitations on the actions of their plaintiffs (that is, their applicants), stalkers who successfully petition for restraining orders (which are easily had by fraud) may follow their targets around; call, text, or email them; or show up at their homes or places of work with no fear of rejection or repercussion. In fact, any acts to drive them off may be represented to authorities as violations of those stalkers’ restraining orders. It’s very conceivable that a stalker could even assault his or her victim with complete impunity, representing the act of violence as self-defense (and at least one such victim of assault has been brought to this blog).