“Accumulated forensic, clinical, and social research strongly suggests that the two most prominent emotions of most stalkers are anger and jealousy…. Such feelings are often consciously felt and acknowledged by the stalker. Nevertheless, these feelings often serve to defend the stalker against more vulnerable feelings that are outside of the stalker’s awareness. Anger can mask feelings of shame and humiliation, the result of rejection by the once idealized object, and/or feelings of loneliness, isolation, and social incompetency.

“Anger may also fuel the pursuit, motivated by envy to damage or destroy that which cannot be possessed…or triggered by a desire to inflict pain on the one who has inflicted pain, the primitive impulse of lex talionis, an eye for an eye.

“Angry pursuit can also repair narcissistic wounds through a fantasized sense of omnipotence and control of the victim. Victim surveys, in fact, have noted that the most common victim perception of the stalker’s motivations is to achieve control….”

—J. Reid Meloy, Ph.D., and Helen Fisher, Ph.D.

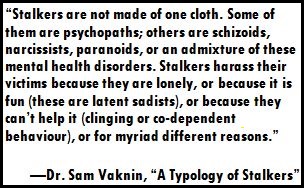

This discussion’s epigraph is drawn from “Some Thoughts on the Neurobiology of Stalking” and touches on a number of the motives of restraining order abuse both by stalkers generally and, in particular, by those stalkers who are most vulnerable to narcissistic wounds, namely, pathological narcissists.

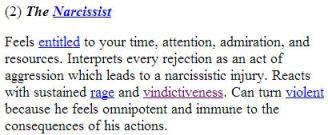

The narcissist is a living emotional pendulum. If [s/he] gets too close to someone emotionally, if [s/he] becomes intimate with someone, [s/he] fears ultimate and inevitable abandonment. [S/he], thus, immediately distances [him- or herself], acts cruelly, and brings about the very abandonment that [s/he] feared in the first place. This is called the ‘approach-avoidance repetition complex’ [Sam Vaknin, Ph.D., “Coping with Various Types of Stalkers: The Narcissist”].

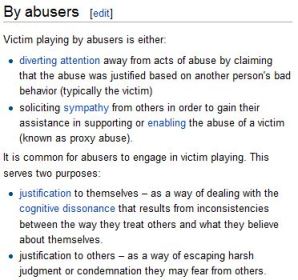

While procurement of a restraining order is commonly perceived as the definitive act of rejection, possibly rejection of a stalker’s advances, it may in fact be an act of possession and control by a stalker (a perverse form of wish fulfillment). A restraining order indelibly stamps the presence of a stalker onto the public face of his or her target (“I own you”). It further disarms the target and mars his or her life, possibly to an extremity. Per Meloy and Fisher, a stalker achieves control and damages or destroys that which cannot be possessed. The “connection,” furthermore, can be repeatedly revisited and harm perpetually refreshed through exploitation of legal process.

While procurement of a restraining order is commonly perceived as the definitive act of rejection, possibly rejection of a stalker’s advances, it may in fact be an act of possession and control by a stalker (a perverse form of wish fulfillment). A restraining order indelibly stamps the presence of a stalker onto the public face of his or her target (“I own you”). It further disarms the target and mars his or her life, possibly to an extremity. Per Meloy and Fisher, a stalker achieves control and damages or destroys that which cannot be possessed. The “connection,” furthermore, can be repeatedly revisited and harm perpetually refreshed through exploitation of legal process.

The authors of the epigraph use the phrase attachment pathology. For a stalker who’s formed an unreciprocated attachment or an unauthorized one (as in the case of someone who’s married), a restraining order presents the treble satisfactions of counter-rejection (“I reject you back” or “I reject you back first”), revenge for not meeting the authoritarian expectations of the stalker, and possession/control. Procurement of a restraining order literally enables a false petitioner to revise the truth into one more favorable to his or her interests or wishes (cf. DARVO: Deny, Attack, and Reverse Victim and Offender). A judge is a rapt audience who only has the petitioner’s account on which to base his or her determination. The only “facts” that s/he’s privy to are the ones provided by the restraining order applicant.

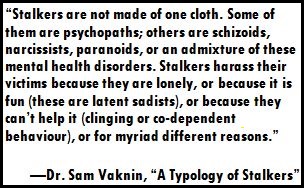

In “Female Stalkers, Part 2: Checklist of Stalking and Harassment Behaviors,” psychologist Tara Palmatier identifies use of “the court and law enforcement to harass” as a female stalking tactic (“e.g., making false allegations, filing restraining orders, petitioning the court for frivolous changes in custody, etc.”), and this form of abuse likely is more typically employed by women against men (women tending “to be more ‘creatively aggressive’ in their stalking acts”). Anecdotal reports to this blog’s author, however, indicate that male stalkers (jilted or high-conflict exes and attention-seeking “admirers”) also engage in this form of punitive subversion against women. (Dr. Palmatier acknowledges as much but explains, “I tailor myself writing for a male audience.”)

Clinical terms for this kind of stalking—less stringent in their scope than legal definitions of stalking, which usually concern threat to personal safety—are “obsessive relational intrusion, intrusive contact, aberrant courtship behavior, obsessional pursuit, and unwanted pursuit behavior,” among others (Katherine S-L. Lau and Delroy L. Paulhus, “Profiling the Romantic Stalker”).

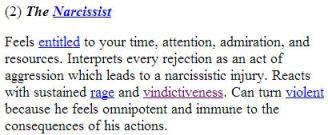

For someone with narcissistic personality disorder, someone, that is, who lives for attention (and is only capable of “aberrant courtship behavior”), a restraining order is a cornucopia, a source of infinitely renewing psychic nourishment, because it can’t fail to titillate an audience and excite drama.

For someone with narcissistic personality disorder, someone, that is, who lives for attention (and is only capable of “aberrant courtship behavior”), a restraining order is a cornucopia, a source of infinitely renewing psychic nourishment, because it can’t fail to titillate an audience and excite drama.

(As noted in The Psychology of Stalking: Clinical and Forensic Perspectives, “Axis II personality disorders are…evident in a majority of stalkers, particularly Cluster B [which includes the narcissistic and borderline personality-disordered]”).

Per the DSM-IV, a narcissist evinces:

A. A pervasive pattern of grandiosity (in fantasy or behavior), need for admiration, and lack of empathy, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by five (or more) of the following:

1. Has a grandiose sense of self-importance (e.g., exaggerates achievements and talents, expects to be recognized as superior without commensurate achievements).

2. Is preoccupied with fantasies of unlimited success, power, brilliance, beauty, or ideal love.

3. Believes that he or she is “special” and unique and can only be understood by, or should associate with, other special or high-status people (or institutions).

4. Requires excessive admiration.

5. Has a sense of entitlement, i.e., unreasonable expectations of especially favorable treatment or automatic compliance with his or her expectations.

6. Is interpersonally exploitative, i.e., takes advantage of others to achieve his or her own ends.

7. Lacks empathy: is unwilling to recognize or identify with the feelings and needs of others.

8. Is often envious of others or believes that others are envious of him or her.

9. Shows arrogant, haughty behaviors or attitudes.

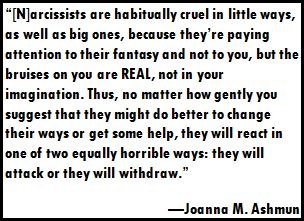

Correspondences between this clinical definition and what might popularly be regarded as the traits of a stalker are uncanny (e.g., preoccupation with fantasies of “ideal love,” dependence on admiration not necessarily due, interpersonal exploitation, and an inability to identify with or a disregard for others’ feelings). It further suggests why a narcissist wouldn’t scruple about abusing legal process to realize malicious ends.

In “Threatened Egotism, Narcissism, Self-Esteem, and Direct and Displaced Aggression: Does Self-Love or Self-Hate Lead to Violence?”, psychologists Brad Bushman and Roy Baumeister observe that aggressively hurtful behavior is more likely to originate from narcissistic arrogance than from insecurity:

In “Threatened Egotism, Narcissism, Self-Esteem, and Direct and Displaced Aggression: Does Self-Love or Self-Hate Lead to Violence?”, psychologists Brad Bushman and Roy Baumeister observe that aggressively hurtful behavior is more likely to originate from narcissistic arrogance than from insecurity:

[I]t has been widely asserted that low self-esteem is a cause of violence (e.g., Kirschner, 1992; Long, 1990; Oates & Forrest, 1985; Schoenfeld, 1988; Wiehe, 1991). According to this theory, certain people are prompted by their inner self-doubts and self-dislike to lash out against other people, possibly as a way of gaining esteem or simply because they have nothing to lose.

A contrary view was proposed by Baumeister, Smart, and Boden (1996). On the basis of an interdisciplinary review of research findings regarding violent, aggressive behavior, they proposed that violence tends to result from very positive views of self that are impugned or threatened by others. In this analysis, hostile aggression was an expression of the self’s rejection of esteem-threatening evaluations received from other people.

The DSM-5 notes that for the narcissist, “positive views of self” are everything (and others’ feelings nothing). Diagnostic criteria are:

A. Significant impairments in personality functioning manifest by:

1. Impairments in self functioning (a or b):

a. Identity: Excessive reference to others for self-definition and self-esteem regulation; exaggerated self-appraisal may be inflated or deflated, or vacillate between extremes; emotional regulation mirrors fluctuations in self-esteem.

b. Self-direction: Goal-setting is based on gaining approval from others; personal standards are unreasonably high in order to see oneself as exceptional, or too low based on a sense of entitlement; often unaware of own motivations.

AND

2. Impairments in interpersonal functions (a or b):

a. Empathy: Impaired ability to recognize or identify with the feelings and needs of others; excessively attuned to reactions of others, but only if perceived as relevant to self; over- or underestimate of own effect on others.

b. Intimacy: Relationships largely superficial and exist to serve self-esteem regulation; mutuality constrained by little genuine interest in others’ experiences and predominance of a need for personal gain.

B. Pathological personality traits in the following domain:

1. Antagonism, characterized by:

a. Grandiosity: Feelings of entitlement, either overt or covert; self-centeredness; firmly holding to the belief that one is better than others; condescending toward others.

b. Attention seeking: Excessive attempts to attract and be the focus of the attention of others; admiration seeking.

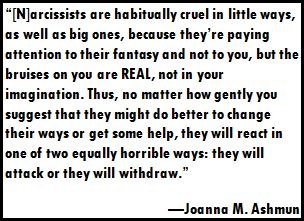

The picture that emerges from clinical observations of the narcissistic personality is one of a person who has no capacity to identify with others’ feelings, a fantastical conception of love, and unreasonable expectations of others and an irrational antagonism toward those who disappoint his or her wishes.

The picture that emerges from clinical observations of the narcissistic personality is one of a person who has no capacity to identify with others’ feelings, a fantastical conception of love, and unreasonable expectations of others and an irrational antagonism toward those who disappoint his or her wishes.

It’s further commonly observed that narcissists’ antagonism toward anyone whom they perceive as critical of them—that is, as a threat to their “positive views of self”—is boundless. The object, then, of a narcissist’s attachment pathology who rejects him or her (disappointing his or her “magical fantasies”), who challenges his or her entitlement, or who manifests disdain or condescension toward the narcissist (even in the form of sympathy) becomes instead the object of the narcissist’s wrath. As psychologist Linda Martinez-Lewi notes, “For the narcissist, revenge is sweet. It’s where they live in their delusional, treacherous minds.”

Narcissists adopt a predictable cycle of Use, Abuse, Dispose. This pathological repetition can last a few weeks or decades…. With a narcissist, there is never an authentic relationship. He/she is a grandiose false self without conscience, empathy, or compassion. Narcissists are ruthless and exploitive to the core [Linda Martinez-Lewi, Ph.D., “Narcissistic Relationship Cycle: Use, Abuse, Dispose”].

The restraining order process, because it enables a petitioner to present a false self and caters to fraudulent representation, is a medium of vengeance ideally suited to a narcissistic stalker. Its exploitation plays to a narcissist’s strengths: social savvy, cunning, and persuasiveness. Its value as an instrument of abuse, furthermore, is unmatched, offering for a minimal investment of time and energy the rewards of public disparagement and alienation of his or her victim, as well as impairment of that victim’s future prospects.

There are sociopathic narcissists who will not be satisfied until their ‘enemy’ is completely vanquished—emotionally, psychologically, financially. They seek revenge, not for what has been done to them but [for] what they perceive in a highly deluded way…has been done to them [Linda Martinez-Lewi, Ph.D., “Sociopathic Narcissists—Relentlessly Cruel”].

Fraudulent abuse of legal process elevates the narcissistic stalker to prime mover and puppet-master over his or her prey and compensates his or her disappointment of “ideal love” with the commensurate satisfactions of “unlimited power” over his or her victim and an infinitely renewable source of ego-fueling attention. By his or her false representations to the court, the narcissist’s fantasies become “the truth.” S/he’s literally able to refashion reality to conform to the false conception s/he favors.

Fraudulent abuse of legal process elevates the narcissistic stalker to prime mover and puppet-master over his or her prey and compensates his or her disappointment of “ideal love” with the commensurate satisfactions of “unlimited power” over his or her victim and an infinitely renewable source of ego-fueling attention. By his or her false representations to the court, the narcissist’s fantasies become “the truth.” S/he’s literally able to refashion reality to conform to the false conception s/he favors.

In conclusion, an observation by psychologist Stanton Samenow:

The narcissist may not commit an act that is illegal, but the damage [s/he] does may be devastating. In fact, because the narcissist appears to be law-abiding, others may not be suspicious of him [or her] leaving him [or her] freer to pursue his [or her] objectives, no matter at whose expense. I have found that the main difference between the narcissist and antisocial individual, in most instances, is that the former has been shrewd or slick enough not to get caught…breaking the law.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

Learning the ins and outs of restraining order litigation has for this writer been an ongoing educational process bordering on a descent into hell that he’s only submitted to with a great deal of teeth-gnashing. In my state (Arizona), it’s possible for a plaintiff who’s petitioned for a restraining order in civil court to return to the same court and file a motion to have it vacated (canceled). Presumably (and I say “presumably,” because laws and protocols vary from state to state), similar provisions are universal.

Learning the ins and outs of restraining order litigation has for this writer been an ongoing educational process bordering on a descent into hell that he’s only submitted to with a great deal of teeth-gnashing. In my state (Arizona), it’s possible for a plaintiff who’s petitioned for a restraining order in civil court to return to the same court and file a motion to have it vacated (canceled). Presumably (and I say “presumably,” because laws and protocols vary from state to state), similar provisions are universal.

Noteworthy finally is Ms. Malloy’s acknowledgment that false allegations of violence, which are devastating in the emotional oppression, humiliation, and social and professional havoc they wreak on the falsely accused, are used strategically to gain leverage in divorce proceedings.

Noteworthy finally is Ms. Malloy’s acknowledgment that false allegations of violence, which are devastating in the emotional oppression, humiliation, and social and professional havoc they wreak on the falsely accused, are used strategically to gain leverage in divorce proceedings.

Disturbing, also, are that the phrase miscarriages of justice is typically only applied to wrongful criminal convictions and that false allegations are discounted as contributing significantly to the number of miscarriages of justice, when in fact they’re responsible for the majority of them. Fraudulent claims are certainly unexceptional in civil proceedings, and the successes of fraudulent claims in civil court are just as much miscarriages of justice as failures of the system that result in false criminal convictions are.

Disturbing, also, are that the phrase miscarriages of justice is typically only applied to wrongful criminal convictions and that false allegations are discounted as contributing significantly to the number of miscarriages of justice, when in fact they’re responsible for the majority of them. Fraudulent claims are certainly unexceptional in civil proceedings, and the successes of fraudulent claims in civil court are just as much miscarriages of justice as failures of the system that result in false criminal convictions are. The first of these important facts is that the nanny state issues restraining orders carelessly, tactlessly, and callously. Their recipients are completely bewildered, and no one actually explains to them what a restraining order signifies, what its specific prohibitions are, or anything else. If a cop is involved, s/he may impress upon a restraining order recipient that the court’s order should be “taken very seriously.” (“What should be taken very seriously?” “The court’s order!”) That’s it. Not one person involved even inquires, for example, whether the restraining order recipient is sighted (as opposed to stone blind), mentally competent, or knows how to read. Restraining orders are casually dispensed (millions of them, each year) and then, unless they’re violated intentionally or accidentally (and motive doesn’t matter; the cops swoop in, regardless), they’re dispensed with: “NEXT!” “NEXT!” “NEXT!” It’s a revolving-door process that’s administered by conveyor belt but enforced with rigorous menace. That’s the first important fact.

The first of these important facts is that the nanny state issues restraining orders carelessly, tactlessly, and callously. Their recipients are completely bewildered, and no one actually explains to them what a restraining order signifies, what its specific prohibitions are, or anything else. If a cop is involved, s/he may impress upon a restraining order recipient that the court’s order should be “taken very seriously.” (“What should be taken very seriously?” “The court’s order!”) That’s it. Not one person involved even inquires, for example, whether the restraining order recipient is sighted (as opposed to stone blind), mentally competent, or knows how to read. Restraining orders are casually dispensed (millions of them, each year) and then, unless they’re violated intentionally or accidentally (and motive doesn’t matter; the cops swoop in, regardless), they’re dispensed with: “NEXT!” “NEXT!” “NEXT!” It’s a revolving-door process that’s administered by conveyor belt but enforced with rigorous menace. That’s the first important fact.

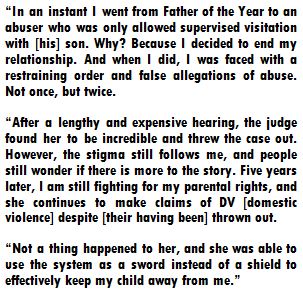

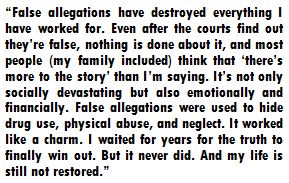

The very real if inconvenient truth remains that victims of false allegations made to authorities and the courts present with the same symptoms highlighted in the epigraph: “fear, anxiety, nervousness, self-blame, anger, shame, and difficulty sleeping”—among a host of others. And that’s just the ones who aren’t robbed of everything that made their lives meaningful, including home, property, and family. In the latter case, post-traumatic stress disorder may be the least of their torments. They may be left homeless, penniless, childless, and emotionally scarred.

The very real if inconvenient truth remains that victims of false allegations made to authorities and the courts present with the same symptoms highlighted in the epigraph: “fear, anxiety, nervousness, self-blame, anger, shame, and difficulty sleeping”—among a host of others. And that’s just the ones who aren’t robbed of everything that made their lives meaningful, including home, property, and family. In the latter case, post-traumatic stress disorder may be the least of their torments. They may be left homeless, penniless, childless, and emotionally scarred.

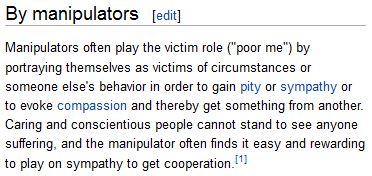

Right, the faker (opportunist, easy-outer, buck-passer, hysteric, bully, vengeance- or attention-seeker, crank, sociopath, neurotic, disordered personality, etc.).

Right, the faker (opportunist, easy-outer, buck-passer, hysteric, bully, vengeance- or attention-seeker, crank, sociopath, neurotic, disordered personality, etc.). What I discovered was that group-bullying certainly is a recognized social phenomenon among kids, and it’s one that’s given rise to the coinage cyberbullying and been credited with inspiring teen suicide. The clinical term for this conduct is

What I discovered was that group-bullying certainly is a recognized social phenomenon among kids, and it’s one that’s given rise to the coinage cyberbullying and been credited with inspiring teen suicide. The clinical term for this conduct is

“I am a landlord, and on Jan. 22, I had the sheriff issue a tenant/roommate a ‘notice to quit’ by the end of the month. The tenant, in retaliation the very next day, requested from the courts that I be slapped with a restraining order and be ordered to stay 100 yards away from her. I guess, lucky for me, the judge did not grant her the 100 yards, which would have gotten me out of my own house.

“I am a landlord, and on Jan. 22, I had the sheriff issue a tenant/roommate a ‘notice to quit’ by the end of the month. The tenant, in retaliation the very next day, requested from the courts that I be slapped with a restraining order and be ordered to stay 100 yards away from her. I guess, lucky for me, the judge did not grant her the 100 yards, which would have gotten me out of my own house. “Narcissistic people do fall in love, but they usually fall in love with being in love—and not with you. They crave the excitement of love, but are quickly disappointed when it becomes a relationship—and not just a trip into fantasy.”

“Narcissistic people do fall in love, but they usually fall in love with being in love—and not with you. They crave the excitement of love, but are quickly disappointed when it becomes a relationship—and not just a trip into fantasy.” Something I neglected to explicitly observe in the recent post referenced in the introduction that may merit observation is that all narcissists are stalkers (whether latent or active) insofar as the objects of narcissists’ romance fantasies are always merely objects to them (psycho-emotional gas pumps); they’re never subjects. What distinguishes the narcissistic stalker is that s/he’s seldom recognized for what s/he is, so s/he’s seldom rejected for what s/he is. Realize that the difference between normal pursuit behavior and aberrant pursuit behavior may be nothing more than how the pursued feels about it. Narcissists choose targets they perceive as vulnerable (empathic, tolerant, and pliable).

Something I neglected to explicitly observe in the recent post referenced in the introduction that may merit observation is that all narcissists are stalkers (whether latent or active) insofar as the objects of narcissists’ romance fantasies are always merely objects to them (psycho-emotional gas pumps); they’re never subjects. What distinguishes the narcissistic stalker is that s/he’s seldom recognized for what s/he is, so s/he’s seldom rejected for what s/he is. Realize that the difference between normal pursuit behavior and aberrant pursuit behavior may be nothing more than how the pursued feels about it. Narcissists choose targets they perceive as vulnerable (empathic, tolerant, and pliable). Once the other fails to satisfy the psycho-emotional needs of the narcissist, corrupts his or her fantasy, or by intimacy threatens the autonomy of the narcissist or the reality s/he’s primarily invested in, the narcissist’s pathology is such that s/he can instantly blame the other (whom the narcissist targeted in the first place) for his or her perceived “betrayal.”

Once the other fails to satisfy the psycho-emotional needs of the narcissist, corrupts his or her fantasy, or by intimacy threatens the autonomy of the narcissist or the reality s/he’s primarily invested in, the narcissist’s pathology is such that s/he can instantly blame the other (whom the narcissist targeted in the first place) for his or her perceived “betrayal.”

In “

In “

Rape and domestic violence happen. There’s no question about it. There’s likewise no question that their effects may be damaging beyond either qualification or quantification.

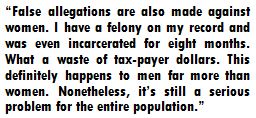

Rape and domestic violence happen. There’s no question about it. There’s likewise no question that their effects may be damaging beyond either qualification or quantification. A significant number, if not the majority, of respondents to this blog who report being the victims of false allegations on restraining orders—particularly the ones who detail their stories at length—are women. This doesn’t mean that women, who represent less than 20% of restraining order defendants, are more commonly the victims of false allegations. It’s indicative, rather, of women’s disposition to socially connect and express their pain, indignity, and outrage. (Women, furthermore, aren’t perceived as dangerous and deviant, so they feel less insecure about publicly declaiming their innocence; they have the greater expectation of being believed and receiving sympathy.)

A significant number, if not the majority, of respondents to this blog who report being the victims of false allegations on restraining orders—particularly the ones who detail their stories at length—are women. This doesn’t mean that women, who represent less than 20% of restraining order defendants, are more commonly the victims of false allegations. It’s indicative, rather, of women’s disposition to socially connect and express their pain, indignity, and outrage. (Women, furthermore, aren’t perceived as dangerous and deviant, so they feel less insecure about publicly declaiming their innocence; they have the greater expectation of being believed and receiving sympathy.) If you imagine there are hard-and-fast rules that apply to what a judge can issue a restraining order for, think again. Grounds for establishing “harassment” or vague emotional allegations like fear need only be their plaintiffs’ assertion. Plaintiffs don’t even

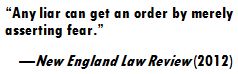

If you imagine there are hard-and-fast rules that apply to what a judge can issue a restraining order for, think again. Grounds for establishing “harassment” or vague emotional allegations like fear need only be their plaintiffs’ assertion. Plaintiffs don’t even

Ignore that and consider what judge, in the “bad old days” before restraining orders existed, would have allowed a woman to be publicly labeled a rapist, merely by implication.

Ignore that and consider what judge, in the “bad old days” before restraining orders existed, would have allowed a woman to be publicly labeled a rapist, merely by implication.

In fact, what it and any number of others’ ordeals show is that when you offer people an easy means to excite drama and conflict, they’ll exploit it.

In fact, what it and any number of others’ ordeals show is that when you offer people an easy means to excite drama and conflict, they’ll exploit it. Her coterie of girlfriends is transposed straight from the halls of high school. They’re less physically favored than the leader of their pack and content to warm themselves in her aura. The adolescent intrigue injects some color into their treadmill lives, and they savor the vicarious thrill of the hunt. The man is a topic of their daily conversation. The women feel young again for a few months, like conspirators in an unconsummated teen crush.

Her coterie of girlfriends is transposed straight from the halls of high school. They’re less physically favored than the leader of their pack and content to warm themselves in her aura. The adolescent intrigue injects some color into their treadmill lives, and they savor the vicarious thrill of the hunt. The man is a topic of their daily conversation. The women feel young again for a few months, like conspirators in an unconsummated teen crush. The life of the man who’d hospitably welcomed the strangers, shaking hands in good faith and doling out mugs of cheer, is trashed: multiple trips to the police precinct to answer false charges and appeals to the court that only invite censure and further abuse. His record, formerly that of an invisible man, becomes hopelessly corrupted. His artistic endeavor, a labor of love that he’d plied himself at for years and on which he’d banked his future joy and financial comfort, is predictably derailed.

The life of the man who’d hospitably welcomed the strangers, shaking hands in good faith and doling out mugs of cheer, is trashed: multiple trips to the police precinct to answer false charges and appeals to the court that only invite censure and further abuse. His record, formerly that of an invisible man, becomes hopelessly corrupted. His artistic endeavor, a labor of love that he’d plied himself at for years and on which he’d banked his future joy and financial comfort, is predictably derailed.

A man eyes a younger, attractive woman at work every day. She’s impressed by him, also, and reciprocates his interest. They have a brief sexual relationship that, unknown to her, is actually an extramarital affair, because the man is married. The younger woman, having naïvely trusted him, is crushed when the man abruptly drops her, possibly cruelly, and she then discovers he has a wife. Maybe she openly confronts him at work. Maybe she calls or texts him. Maybe repeatedly. The man, concerned to preserve appearances and his marriage, applies for a restraining order alleging the woman is harassing him, has become fixated on him, is unhinged. As evidence, he provides phone records, possibly dating from the beginning of the affair—or pre-dating it—besides intimate texts and emails. He may also provide tokens of affection she’d given him, like a birthday card the woman signed and other romantic trifles, and represent them as unwanted or even (implicitly) disturbing. “I’m a married man, Your Honor,” he testifies, admitting nothing, “and this woman’s conduct is threatening my marriage, besides my status at work.”

A man eyes a younger, attractive woman at work every day. She’s impressed by him, also, and reciprocates his interest. They have a brief sexual relationship that, unknown to her, is actually an extramarital affair, because the man is married. The younger woman, having naïvely trusted him, is crushed when the man abruptly drops her, possibly cruelly, and she then discovers he has a wife. Maybe she openly confronts him at work. Maybe she calls or texts him. Maybe repeatedly. The man, concerned to preserve appearances and his marriage, applies for a restraining order alleging the woman is harassing him, has become fixated on him, is unhinged. As evidence, he provides phone records, possibly dating from the beginning of the affair—or pre-dating it—besides intimate texts and emails. He may also provide tokens of affection she’d given him, like a birthday card the woman signed and other romantic trifles, and represent them as unwanted or even (implicitly) disturbing. “I’m a married man, Your Honor,” he testifies, admitting nothing, “and this woman’s conduct is threatening my marriage, besides my status at work.”

I hear weekly if not daily from victims of second-wave feminist rhetoric and the influence it’s exercised over the past 30 years on social perceptions that translate to public policy. Today most Americans assume that the instrument born of 60s and 70s consciousness-raising efforts by equity feminists, the civil restraining order, is rarely abused. This falsehood is promulgated through the unconsciousness-raising efforts of radical feminist usurpers who’ve left proto-feminists like philosopher Christina Hoff Sommers asking,

I hear weekly if not daily from victims of second-wave feminist rhetoric and the influence it’s exercised over the past 30 years on social perceptions that translate to public policy. Today most Americans assume that the instrument born of 60s and 70s consciousness-raising efforts by equity feminists, the civil restraining order, is rarely abused. This falsehood is promulgated through the unconsciousness-raising efforts of radical feminist usurpers who’ve left proto-feminists like philosopher Christina Hoff Sommers asking,  The Wikipedia entry I’ve cited explains rape culture includes behaviors like “victim-blaming” and “trivializing rape.” Considering that a significant proportion of restraining order abuses may be instances of victim-blaming, that is, of abusers’ (including violent abusers’) inducing the state to harass, humiliate, and drop the hammer on their victims; and considering that this abuse (characterized by some as “rape”) is arguably trivialized by its being categorically ignored or denied, a case arises for the reverse application of the phrase rape culture.

The Wikipedia entry I’ve cited explains rape culture includes behaviors like “victim-blaming” and “trivializing rape.” Considering that a significant proportion of restraining order abuses may be instances of victim-blaming, that is, of abusers’ (including violent abusers’) inducing the state to harass, humiliate, and drop the hammer on their victims; and considering that this abuse (characterized by some as “rape”) is arguably trivialized by its being categorically ignored or denied, a case arises for the reverse application of the phrase rape culture.