Among the challenges of exposing crookedness in the adjudication of restraining orders is credibility. Power rules, and the people who’ve been abused typically have none. Their plaints are discounted or dismissed.

Among the challenges of exposing crookedness in the adjudication of restraining orders is credibility. Power rules, and the people who’ve been abused typically have none. Their plaints are discounted or dismissed.

Influential and creditworthy commentators have denounced restraining order injustice, including systemic judicial misconduct, and they’ve in fact done it for decades. But they aren’t saying what the politically entitled want to hear, so the odd peep and quibble are easily drowned in the maelstrom.

Below is a exquisite journalistic exposé that I can’t simply provide a link to because the nearly 20-year-old reportage is only preserved on the Internet by proxy hosts (for example, here).

The article, “N.J. Judges Told to Ignore Rights in Abuse TROs,” is by Russ Bleemer and was published in the April 24, 1995 edition of the New Jersey Law Journal.

New Jersey attorneys corroborate that the rigid policy it scrutinizes still obtains today. What’s more, the general prescriptions of the New Jersey training judge on whom the articles focuses arguably inform restraining order policy nationwide. The only things dated about the article are (1) judges’ being “trained on the issue of domestic violence” is no longer “unique” to New Jersey but is  contractually mandated everywhere in return for courts’ receiving hefty federal grants under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), which grants average out at over $500,000 per; and (2) the resultant policy now injures not only men who are fingered as abusers in five-minute procedures that are often merely perfunctory.

contractually mandated everywhere in return for courts’ receiving hefty federal grants under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), which grants average out at over $500,000 per; and (2) the resultant policy now injures not only men who are fingered as abusers in five-minute procedures that are often merely perfunctory.

According to the same complacently biased “standards,” it also trashes the lives of accused women, who are not infrequently prosecuted by other women (including their mothers, daughters, and sisters).

______________

Text of “N.J. Judges Told to Ignore Rights in Abuse TROs” by Russ Bleemer (Copyright © 1995 American Lawyer Newspapers Group, Inc.):

On Friday, at a training session at the Hughes Justice Complex in Trenton, novitiate municipal judged were given the “scared straight” version of dealing with requests for temporary restraining orders in domestic violence cases.

The recommendation: Issue the order, or else.

Failing to issue temporary restraining orders in domestic violence cases, the judges are told, will turn them into fodder for headlines.

They’re also instructed not to worry about the constitution.

The state law carries a strong presumption in favor of granting emergency TROs for alleged domestic violence victims, the new judges were told at the seminar run by the Administrative Office of the Courts. Public sentiment, mostly due to the O.J. Simpson case, runs even stronger.

The judges’ training is rife with hyperbole apparently designed to shock the newcomers. It sets down a rigid procedure, one that the trainers say is the judges’ only choice under a tough 1991 domestic violence law and its decade-old predecessor.

The judges’ training is rife with hyperbole apparently designed to shock the newcomers. It sets down a rigid procedure, one that the trainers say is the judges’ only choice under a tough 1991 domestic violence law and its decade-old predecessor.

Since the Legislature has made domestic violence a top priority, municipal court judges are instructed that they can do their part by issuing temporary restraining orders pronto.

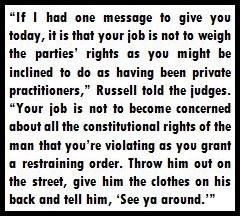

“Throw him out on the street,” said trainer and municipal court judge Richard Russell at a similar seminar a year ago, “give him the clothes on his back, and tell him, ‘See ya around.’”

This napalm approach to implementing the domestic violence statute has some state judges talking. No one disputes the presumption in the law of granting a TRO, and there have been no serious court challenges to the statute’s ex parte provisions.

The strident teaching, however, doesn’t always sit well with some judges, even those who characterize the instruction as deliberate verbal flares directed at a worthy goal.

“[It’s] one of the most inflammatory things I have ever heard,” says one municipal court judge, who asked not to be identified, about a presentation held last year. “We’re supposed to have the courage to make the right decisions, not do what is ‘safe.’”

At the same time, even former and current municipal and Superior Court judges who are critical of the seminar have words of admiration for the candor of trainers Russell, Somerset County Superior Court Judge Graham Ross and Nancy Kessler, chief of juvenile and family services for the AOC. One municipal court judge says that while the statements reflect an incorrect approach, “I wouldn’t be real keen to inhibit the trainers at these sessions from exhibiting their honest opinions.”

For their part, Russell and Kessler say they are doing what the law says they should do—protecting victims, which in turn can save lives. Ross didn’t return telephone calls about the training. He, Russell and Kessler were scheduled to conduct Friday’s program for new judges, a program Kessler says the trio has conducted for judges at least five times since the law was passed.

The law, N.J.S.A. 2C:25-17 et seq., requires judges to be trained on the issue of domestic violence, a requirement that women’s rights advocates say is unique. The TRO provisions also were reemphasized three years ago, encouraging the use of such orders after a municipal court judge hears from one complainant.

The law, N.J.S.A. 2C:25-17 et seq., requires judges to be trained on the issue of domestic violence, a requirement that women’s rights advocates say is unique. The TRO provisions also were reemphasized three years ago, encouraging the use of such orders after a municipal court judge hears from one complainant.

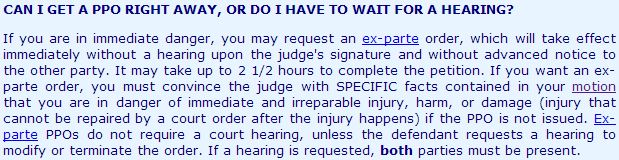

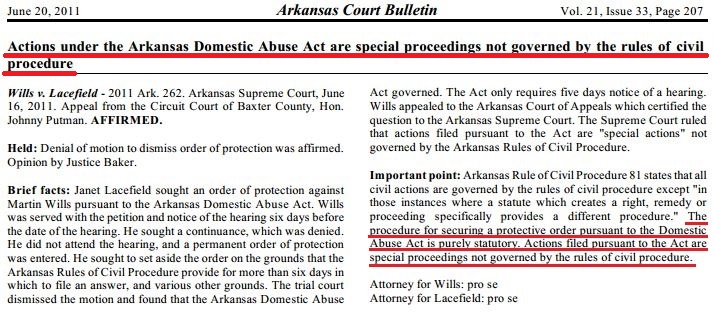

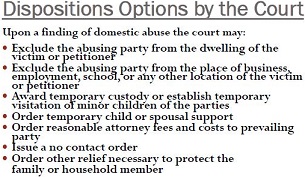

Under N.J.S.A. 2C:25-28, municipal court judges assigned to cover for their Superior Court counterparts at nights and on weekends and holidays can issue an ex parte TRO, which is subject to a hearing within 10 days in the Superior Court’s family part “when necessary to protect the life, health or well-being of a victim on whose behalf the relief is sought.”

The TRO may prohibit the defendant from returning to the scene of the alleged act, strip the defendant of firearms or weapons, and provide “any other appropriate relief.” The law also says that the emergency relief “shall be granted for good cause shown.”

Dating Relationships Included

The training, however, stresses the Legislature’s urgency in passing the law, which last year was amended again to extend possible domestic violence situations to dating relationships. The trainers encourage the judges to focus on the legislative findings, which, in emphasizing rapid law enforcement response, state “that there are thousands of persons in this State who are regularly beaten, tortured and in some cases even killed by their spouses or cohabitants.”

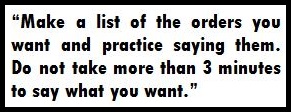

This, said Kessler at a training session last year, is justification for an approach advocated by Russell: Talk to the complainant, talk to the reporting officer, issue the TRO, and let the family court sort it out later.

This, said Kessler at a training session last year, is justification for an approach advocated by Russell: Talk to the complainant, talk to the reporting officer, issue the TRO, and let the family court sort it out later.

On a tape of the April 1994 session obtained by the Law Journal, Kessler told the judges that “in that legislative findings section, people are told to interpret this law broadly in order to maximize protection for the victim. So if anybody ever came back at you and said, ‘Gee, that’s a real reach in terms of probable cause,’ you have a legislatively mandated response which is, ‘I erred on the side of caution for the victim.’”

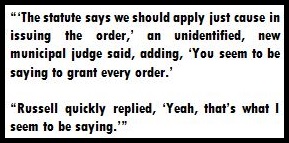

Kessler was reacting to a question that arose during Russell’s presentation. “The statute says we should apply just cause in issuing the order,” an unidentified, new municipal judge said, adding, “You seem to be saying to grant every order.”

Russell quickly replied, “Yeah, that’s what I seem to be saying.”

Russell, a municipal court judge in Ocean City and Woodbine, as well as a partner in Ocean City’s Loveland, Garrett, Russell & Young, answered the question at last year’s seminar after he had spoken for some time on the middle-of-the-night procedures the new judges would have to follow.

At the outset, Russell said that he was on the bench when the original domestic violence act was enacted in 1982 “and that just blew up all of my learning, all my understanding, all my concept of constitutional protections and I had to acclimate myself to a whole new ball game.

“If I had one message to give you today, it is that your job is not to weigh the parties’ rights as you might be inclined to do as having been private practitioners,” Russell told the judges. “Your job is not to become concerned about all the constitutional rights of the man that you’re violating as you grant a restraining order. Throw him out on the street, give him the clothes on his back and tell him, ‘See ya around.’ Your job is to be a wall that is thrown between the two people that are fighting each other and that’s how you can rationalize it. Because that’s what the statute says. The statute says that there is something called domestic violence and it says that it is an evil in our society.”

Not all judges agree with Russell’s approach. Philip Gruccio, a former trial and Appellate Division judge, says that even orders based on ex parte requests require hearings, to a certain extent. “It involves a certain amount of judicial discretion,” he says.

Robert Penza, who retired last year after serving as a family court judge in Morris County for two years, agrees. “I could just never rubber stamp a complaint,” says Penza. “A judge has got to judge.”

Gruccio, who says he is familiar with the work of Russell and Ross on the bench and that both are top notch judges, strongly disagrees with the approach. “My view is that you just can’t say, ‘Forget about the defendant’s rights.’ You can’t say that. It is wrong to say that. It is wrong to train people that constitutional rights aren’t important.”

Gruccio, a professor at Widener University Law School in Wilmington, Del., and director of its judicial administration program, concludes, “I think what has happened is, for emphasis purposes, somebody has lost their way.”

Catering to Popular Objectives

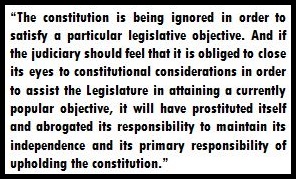

Sitting judges interviewed for this article readily agree with Gruccio. Says one: “The constitution is being ignored in order to satisfy a particular legislative objective. And if the judiciary should feel that it is obliged to close its eyes to constitutional considerations in order to assist the Legislature in attaining a currently popular objective, it will have prostituted itself and abrogated its responsibility to maintain its independence and its primary responsibility of upholding the constitution.”

One municipal court judge who has heard the AOC lecture says, “This is throwing people out of their homes in the middle of the night,” adding, “We have an obligation under our oath of office to be fair, not to be safe.”

One municipal court judge who has heard the AOC lecture says, “This is throwing people out of their homes in the middle of the night,” adding, “We have an obligation under our oath of office to be fair, not to be safe.”

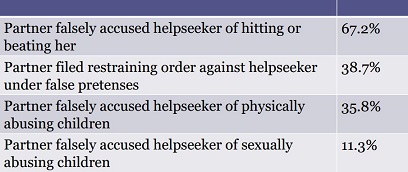

A problem that arises by such wholesale approvals of TROs, judges say, is that word spreads, and litigants can try to use them as a club. Kessler couldn’t provide statistics on the number of TROs that are later dismissed by the family court, but she says that the number is “significant.” She adds that more than 58,000 TROs and amended TROs were issued by New Jersey courts last year, with about 60 percent of the complaints originating in municipal courts.

While some municipal court judges acknowledge that the domestic violence law can create injustices—one calls it “probably the most abused piece of legislation that comes to my mind”—there are counterpoints. Melanie Griffin, executive director of the Commission to Study Sex Discrimination in the Statutes, a legislative commission that drafted much of the 1991 law, says that for every individual who files a false report, “there are 100 women who don’t come in at all and stay there and get beaten.”

Judges who have seen the training presentation say that if anyone objects, they keep it to themselves. Russell says that sometimes “those with no background express disbelief, until we explain the intent of the legislation.”

Moreover, Russell says there is nothing wrong with the teaching approach. Abuse victims, he says, may apply and relinquish TROs repeatedly before they finally do something about breaking away. Once they do so, he says, the Legislature’s prevention goal has been met.

Russell continues: “So when you say to me, am I doing something wrong telling these judges they have to ignore the constitutional protections most people have, I don’t think so. The Legislature described the problem and how to address it, [and] I am doing my job properly by teaching other judges to follow the legislative mandate.”

Russell disputes that the TRO training removes judicial discretion where it is needed. On the tape, Russell and Kessler emphasize that first, the judge must decide whether the domestic violence statute grants jurisdiction over the complainant and the defendant. Russell said last week that he was updating Friday’s lecture to include the 1994 expansion of the domestic violence statute to situations in which the complainant was dating the accused or alleges that the accused is a stalker. The judge also has to speak to the party or review the written material and make a decision whether to proceed. “The judge has to be guided by instinct,” Russell explains, before he or she can go ahead with the TRO.

Says one municipal court judge who also has conducted training and asked not to be named: “I would say, ‘If there is any doubt in your mind about want to do, you should issue the restraining order.’” The judge adds, “I would never approach the topic by saying, ‘Look, these people are stripped of their constitutional rights.’”

Making Headlines

Much of the seminar’s rhetoric alludes to actions that keep the judges out of the headlines, which are mentioned in the taped seminar repeatedly. Near the beginning of his presentation, Judge Graham Ross, reacting to Russell, says that dealing with domestic violence “is not something that we can take a shortcut on. Forgetting about reading your name in the paper—and that certainly is very troubling, I don’t want to read my name—but that’s really secondary.

“The bottom line is we’re trying to protect the victim,” Ross continues. “We don’t want the victim hurt. We don’t want the victim killed. So yes, you don’t want your name in the paper, but you’d feel worse than that if the victim was dead. So yeah, your name will be in the paper…if you’ve done something wrong. And I’ve said that to my municipal court judges. If you don’t follow the law after I told you what to do, I will guarantee that you will be headlines. That’s not a threat. That’s an absolute promise on my part. This is serious stuff.”

The AOC’s Kessler says the media references are a training technique, and judges aren’t influenced by public opinion polls. The focus, she says, follows the statute’s emphasis on protecting victims by dealing with the dynamics of domestic violence and the importance of intervention. “When there is a discussion about headlines,” she says, “it tends to be more in recognition of what they already are aware of and concerned about.”

One former judge agrees that judges don’t work wearing blinders, but says that if worries about bad publicity affect their work, “it defrauds the system.” A current municipal court judge who has been through the training on domestic violence says, “We have to stand back from the hysteria and the newspapers and all and do what’s right.”

One former judge agrees that judges don’t work wearing blinders, but says that if worries about bad publicity affect their work, “it defrauds the system.” A current municipal court judge who has been through the training on domestic violence says, “We have to stand back from the hysteria and the newspapers and all and do what’s right.”

But most others disagreed. The “approach isn’t bad because it’s got a shock value,” says retired judge Robert Penza.

A current municipal court judge liked the realism of the media references. “A newspaper headline can be death to a municipal court judge’s career,” says the long-time jurist, “and the prospect of an unfavorable newspaper headline is a frightening one.” The judge added, however, that attention-getting devices must not be confused with legal principles.

And the judge paid the overall approach a backhanded compliment frequently repeated in some form among the former and current judges contacted for this article. Referring to Russell, the judge declared: “What he said is valuable because he is expressing the state of affairs. He should be commended for his candor, although I must say I find his viewpoint to be anathema.”

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

I’ve tried in earnest to field a lot of

I’ve tried in earnest to field a lot of

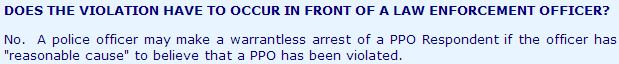

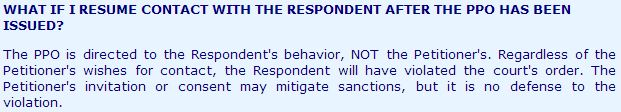

This “proof,” once “entered into the computer system,” authorizes a police officer to arrest the defendant for violating an order of the court that s/he may not even have been given a copy of. The defendant’s so much as saying hello to the plaintiff now qualifies as a crime for which s/he can be arrested and punished.

This “proof,” once “entered into the computer system,” authorizes a police officer to arrest the defendant for violating an order of the court that s/he may not even have been given a copy of. The defendant’s so much as saying hello to the plaintiff now qualifies as a crime for which s/he can be arrested and punished.

Right. (People report answering the phone and actually being told, “Gotcha!”)

Right. (People report answering the phone and actually being told, “Gotcha!”)

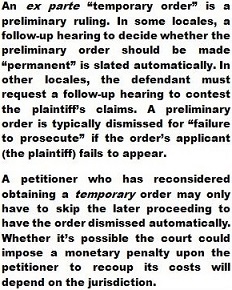

Since I began culling various “

Since I began culling various “ If the restraining order was petitioned in anger or the petitioner simply acted “without thinking,” withdrawing it is furthermore an ethical no-brainer, and it may be sufficient for the petitioner to tell the court that s/he no longer considers the order necessary.

If the restraining order was petitioned in anger or the petitioner simply acted “without thinking,” withdrawing it is furthermore an ethical no-brainer, and it may be sufficient for the petitioner to tell the court that s/he no longer considers the order necessary. Concerns about being prosecuted by the state for falsely alleging fear are unwarranted. Concerns about the state continuing to sniff around a plaintiff’s household, however, aren’t baseless. It happens.

Concerns about being prosecuted by the state for falsely alleging fear are unwarranted. Concerns about the state continuing to sniff around a plaintiff’s household, however, aren’t baseless. It happens.

fulfilled in mere minutes, is agonizing.

fulfilled in mere minutes, is agonizing. A theme that emerges upon consideration of

A theme that emerges upon consideration of  It’s ironic that the focus of those who should be most sensitized to injustice is so narrow. Ironic, moreover, is that “emotional abuse” is frequently a component of state definitions of domestic violence. The state recognizes the harm of emotional violence done in the home but conveniently regards the same conduct as harmless when it uses the state as its instrument.

It’s ironic that the focus of those who should be most sensitized to injustice is so narrow. Ironic, moreover, is that “emotional abuse” is frequently a component of state definitions of domestic violence. The state recognizes the harm of emotional violence done in the home but conveniently regards the same conduct as harmless when it uses the state as its instrument. Here’s yet another irony. Too often the perspectives of those who decry injustices are partisan. Feminists themselves are liable to see only one side.

Here’s yet another irony. Too often the perspectives of those who decry injustices are partisan. Feminists themselves are liable to see only one side. Now consider the motives of false allegations and their certain and potential effects: isolation, termination of employment and impediment to or negation of employability, inaccessibility to children (who are used as leverage), and being forced to live on limited means (while possibly being required under threat of punishment to provide spousal and child support) and perhaps being left with no home to furnish or automobile to drive at all.

Now consider the motives of false allegations and their certain and potential effects: isolation, termination of employment and impediment to or negation of employability, inaccessibility to children (who are used as leverage), and being forced to live on limited means (while possibly being required under threat of punishment to provide spousal and child support) and perhaps being left with no home to furnish or automobile to drive at all.

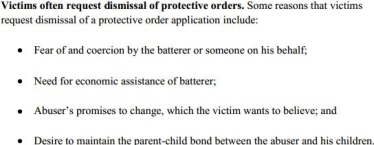

Notable, contrariwise, however, is that the respondent discourages the petitioner of the restraining order, who’s admitted to proceeding impulsively, from following through with her expressed intention to rectify an act that may have been motivated by spite. The respondent is the executive director of

Notable, contrariwise, however, is that the respondent discourages the petitioner of the restraining order, who’s admitted to proceeding impulsively, from following through with her expressed intention to rectify an act that may have been motivated by spite. The respondent is the executive director of

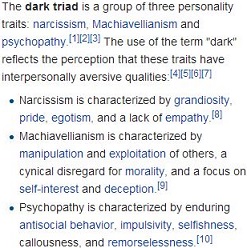

It turns out there’s a sexy phrase for the collective personality traits exhibited by manipulators of this sort: the “

It turns out there’s a sexy phrase for the collective personality traits exhibited by manipulators of this sort: the “

The Dark Triad traits should be associated with preferring casual relationships of one kind or another. Narcissism in particular should be associated with desiring a variety of relationships. Narcissism is the most social of the three, having an approach orientation towards friends (Foster & Trimm, 2008) and an externally validated ‘ego’ (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008). By preferring a range of relationships, narcissists are better suited to reinforce their sense of self. Therefore, although collectively the Dark Triad traits will be correlated with preferring different casual sex relationships, after controlling for the shared variability among the three traits, we expect that narcissism will correlate with preferences for one-night stands and friend[s]-with-benefits.

The Dark Triad traits should be associated with preferring casual relationships of one kind or another. Narcissism in particular should be associated with desiring a variety of relationships. Narcissism is the most social of the three, having an approach orientation towards friends (Foster & Trimm, 2008) and an externally validated ‘ego’ (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008). By preferring a range of relationships, narcissists are better suited to reinforce their sense of self. Therefore, although collectively the Dark Triad traits will be correlated with preferring different casual sex relationships, after controlling for the shared variability among the three traits, we expect that narcissism will correlate with preferences for one-night stands and friend[s]-with-benefits. What we’re talking about in the context of abuse of restraining orders are people who exploit others and then exploit legal process as a convenient means to discard them when they’re through (while whitewashing their own behaviors, procuring additional narcissistic supply in the forms of attention and special treatment, and possibly exacting a measure of revenge if they feel they’ve been criticized or contemned).

What we’re talking about in the context of abuse of restraining orders are people who exploit others and then exploit legal process as a convenient means to discard them when they’re through (while whitewashing their own behaviors, procuring additional narcissistic supply in the forms of attention and special treatment, and possibly exacting a measure of revenge if they feel they’ve been criticized or contemned). I tend to manipulate others to get my way.

I tend to manipulate others to get my way.

The biggest challenge to sensitizing people to abusive restraining order policies that are readily and pervasively exploited by malicious litigants can be summed up in a single word: sex.

The biggest challenge to sensitizing people to abusive restraining order policies that are readily and pervasively exploited by malicious litigants can be summed up in a single word: sex.

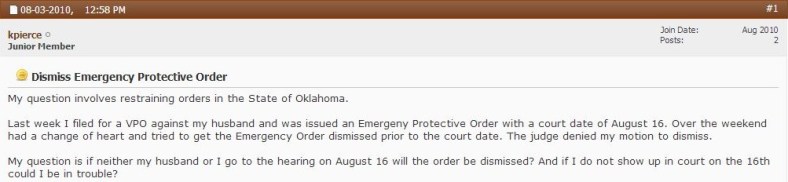

Defendants’ being railroaded, of course, is nothing extraordinary. “Emergency” restraining orders may allow respondents only a weekend to prepare before having to appear in court to answer allegations—very possibly false allegations—that have the potential to permanently alter the course of their lives.

Defendants’ being railroaded, of course, is nothing extraordinary. “Emergency” restraining orders may allow respondents only a weekend to prepare before having to appear in court to answer allegations—very possibly false allegations—that have the potential to permanently alter the course of their lives.

Some feminists categorically can’t be reasoned with. They’re the equivalents of high-conflict courtroom litigants who reason with their feelings. But I don’t get the impression that the author of this blog is one such, and I think there are many self-styled feminists like her out there. She seems very much in earnest and without spiteful motive. Her intentions are well-meaning.

Some feminists categorically can’t be reasoned with. They’re the equivalents of high-conflict courtroom litigants who reason with their feelings. But I don’t get the impression that the author of this blog is one such, and I think there are many self-styled feminists like her out there. She seems very much in earnest and without spiteful motive. Her intentions are well-meaning.

It must be considered, for example, that the authority for the statistic “1 in 4 women will experience domestic violence in her lifetime” cited by this writer (and which is commonly cited) is a pamphlet: “

It must be considered, for example, that the authority for the statistic “1 in 4 women will experience domestic violence in her lifetime” cited by this writer (and which is commonly cited) is a pamphlet: “ What everyone must be brought to appreciate is that a great deal of what’s called “domestic violence” (and, for that matter, “stalking”) depends on subjective interpretation, that is, it’s all about how someone reports feeling (or what someone reports perceiving).

What everyone must be brought to appreciate is that a great deal of what’s called “domestic violence” (and, for that matter, “stalking”) depends on subjective interpretation, that is, it’s all about how someone reports feeling (or what someone reports perceiving). The zealousness of the public and of the authorities and courts to acknowledge people, particularly women, who claim to be “victims” as victims has produced miscarriages of justice that are far more epidemic than domestic violence is commonly said to be. Discernment goes out the window, and lives are unraveled based on finger-pointing. Thanks to feminism’s greasing the gears and to judicial procedures that can be initiated or even completed in minutes, people in the throes of angry impulses can have those impulses gratified instantly. All parties involved—plaintiffs, police officers, and judges—are simply reacting, as they’ve been conditioned to.

The zealousness of the public and of the authorities and courts to acknowledge people, particularly women, who claim to be “victims” as victims has produced miscarriages of justice that are far more epidemic than domestic violence is commonly said to be. Discernment goes out the window, and lives are unraveled based on finger-pointing. Thanks to feminism’s greasing the gears and to judicial procedures that can be initiated or even completed in minutes, people in the throes of angry impulses can have those impulses gratified instantly. All parties involved—plaintiffs, police officers, and judges—are simply reacting, as they’ve been conditioned to.

Judicial partiality in the restraining order arena is coyly called “paternal” by its practitioners. What it’s called by those whose lives are permanently altered by it for the worse is careless, callous, and/or cruel. Allegations that cost people their ambitions, children, life savings, and sanity may be exaggerated, cooked, or spitefully manufactured—sometimes obviously so.

Judicial partiality in the restraining order arena is coyly called “paternal” by its practitioners. What it’s called by those whose lives are permanently altered by it for the worse is careless, callous, and/or cruel. Allegations that cost people their ambitions, children, life savings, and sanity may be exaggerated, cooked, or spitefully manufactured—sometimes obviously so.

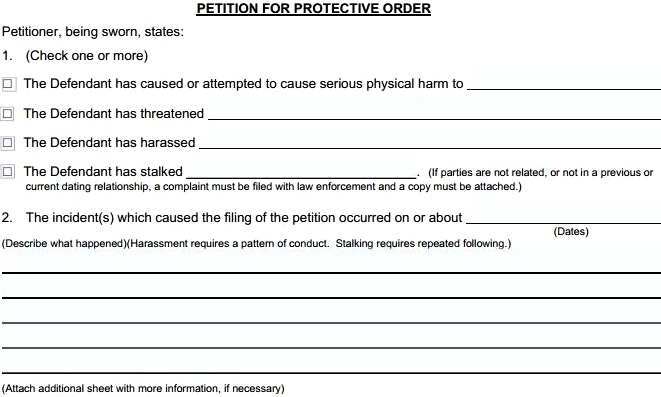

All there is to making allegations on restraining orders is tick boxes and blanks, and there are no bounds imposed upon what allegations can be made. A false applicant merely writes whatever he wants in the spaces provided—and he can use additional pages if he’s feeling inspired. The basis for a woman’s being alleged to be a domestic abuser or even “armed and dangerous” is the unsubstantiated say-so of the petitioner. Can the defendant be a vegetarian single mom or an arthritic, 80-year-old great-grandmother? Sure. The judge who rules on the application won’t have met her and may never even learn what she looks like. She’s just a name.

All there is to making allegations on restraining orders is tick boxes and blanks, and there are no bounds imposed upon what allegations can be made. A false applicant merely writes whatever he wants in the spaces provided—and he can use additional pages if he’s feeling inspired. The basis for a woman’s being alleged to be a domestic abuser or even “armed and dangerous” is the unsubstantiated say-so of the petitioner. Can the defendant be a vegetarian single mom or an arthritic, 80-year-old great-grandmother? Sure. The judge who rules on the application won’t have met her and may never even learn what she looks like. She’s just a name.

The same impulsive emotional reasoning exemplified by this foot-stamping is what’s suggested by the search terms that introduce this post (to which I could have appended thousands more of a similar nature).

The same impulsive emotional reasoning exemplified by this foot-stamping is what’s suggested by the search terms that introduce this post (to which I could have appended thousands more of a similar nature). The thrust of today’s mainstream ideological feminism is to blame, subjugate, and punish, not unify. Feminism has betrayed itself.

The thrust of today’s mainstream ideological feminism is to blame, subjugate, and punish, not unify. Feminism has betrayed itself. Restraining orders are by and large sought impulsively—in the millions every year. Both motives and the engine that generates them are virtually automatic.

Restraining orders are by and large sought impulsively—in the millions every year. Both motives and the engine that generates them are virtually automatic.

Judge Daniel Sanchez issued a restraining order against Letterman based on those allegations. By doing so, it put Letterman on a national list of domestic abusers, gave him a criminal record, took away several of his constitutionally protected rights, and subjected him to criminal prosecution if he contacted Nestler directly or indirectly, or possessed a firearm.

Judge Daniel Sanchez issued a restraining order against Letterman based on those allegations. By doing so, it put Letterman on a national list of domestic abusers, gave him a criminal record, took away several of his constitutionally protected rights, and subjected him to criminal prosecution if he contacted Nestler directly or indirectly, or possessed a firearm. To some degree at least, this understanding restricts all but the mentally ill, who may be delusional, and

To some degree at least, this understanding restricts all but the mentally ill, who may be delusional, and

I’ll give you a for-instance. Let’s say Person A applies for a protection order and claims Person B threatened to rape her and then kill her with a butcher knife.

I’ll give you a for-instance. Let’s say Person A applies for a protection order and claims Person B threatened to rape her and then kill her with a butcher knife. Person A circulates the details she shared with the court, which are embellished and further honed with repetition, among her friends and colleagues over the ensuing days, months, and years.

Person A circulates the details she shared with the court, which are embellished and further honed with repetition, among her friends and colleagues over the ensuing days, months, and years.

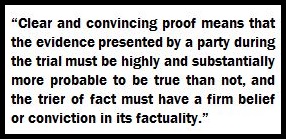

Note that the odds of its being accurate, assuming all conditions are equal, may be only slightly better than a coin flip’s.

Note that the odds of its being accurate, assuming all conditions are equal, may be only slightly better than a coin flip’s. Restraining orders are understood to be issued to “sickos.” Nobody hears “restraining order” and thinks “Little Rascal.”

Restraining orders are understood to be issued to “sickos.” Nobody hears “restraining order” and thinks “Little Rascal.”

No argument here.

No argument here. to the procurement of restraining orders, which are presumed to be sought by those in need of protection.

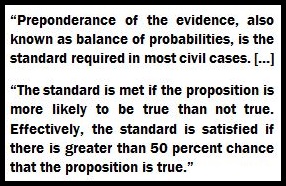

to the procurement of restraining orders, which are presumed to be sought by those in need of protection. Such hearings are far more perfunctory than probative. Basically a judge is just looking for a few cue words to run with and may literally be satisfied by a plaintiff’s saying, “I’m afraid.” (Talk show host

Such hearings are far more perfunctory than probative. Basically a judge is just looking for a few cue words to run with and may literally be satisfied by a plaintiff’s saying, “I’m afraid.” (Talk show host

A scratch, a push, a pinch—which may not even have been real but whose allegation had real enough consequences.

A scratch, a push, a pinch—which may not even have been real but whose allegation had real enough consequences. I’ve written recently about the abuse of restraining orders by fraudulent litigants to punish. What needs observation is that the laws themselves, that is, restraining order and domestic violence statutes, are corrupted by the same motive: to punish. Their motive is not simply to protect (a fact that’s borne out by the prosecution of alleged pinchers).

I’ve written recently about the abuse of restraining orders by fraudulent litigants to punish. What needs observation is that the laws themselves, that is, restraining order and domestic violence statutes, are corrupted by the same motive: to punish. Their motive is not simply to protect (a fact that’s borne out by the prosecution of alleged pinchers).

Restraining orders are maliciously abused—not sometimes, but often. Typically this is done in heat to hurt or hurt back, to shift blame for abusive misconduct, or to gain the upper hand in a conflict that may have far-reaching consequences.

Restraining orders are maliciously abused—not sometimes, but often. Typically this is done in heat to hurt or hurt back, to shift blame for abusive misconduct, or to gain the upper hand in a conflict that may have far-reaching consequences.

A recent male respondent to this blog, for example, reports encountering an ex while out with his kids and being lured over, complimented, etc. (“Here, boy! Come!”), following which the woman reported to the police that she was terribly alarmed by the encounter and, while brandishing a restraining order application she’d filled out, had the man charged with stalking. Though the meeting was recorded on store surveillance video and was unremarkable, the woman had no difficulty persuading a male officer that she responded to the man in a friendly manner because she was afraid of him (a single father out with his two little kids). The man also reports (desperately and apologetic for being a “bother”) that he and his children have been baited and threatened on Facebook, including by a female friend of his ex’s and by strangers.

A recent male respondent to this blog, for example, reports encountering an ex while out with his kids and being lured over, complimented, etc. (“Here, boy! Come!”), following which the woman reported to the police that she was terribly alarmed by the encounter and, while brandishing a restraining order application she’d filled out, had the man charged with stalking. Though the meeting was recorded on store surveillance video and was unremarkable, the woman had no difficulty persuading a male officer that she responded to the man in a friendly manner because she was afraid of him (a single father out with his two little kids). The man also reports (desperately and apologetic for being a “bother”) that he and his children have been baited and threatened on Facebook, including by a female friend of his ex’s and by strangers.

What a broader yet nuanced definition of stalking like Dr. Palmatier’s reveals is that what makes someone a stalker isn’t how his or her target perceives him or her; it’s how s/he perceives his or her target: as an object (what stalking literally means is the stealthy pursuit of prey—that is, food).

What a broader yet nuanced definition of stalking like Dr. Palmatier’s reveals is that what makes someone a stalker isn’t how his or her target perceives him or her; it’s how s/he perceives his or her target: as an object (what stalking literally means is the stealthy pursuit of prey—that is, food). Placed in proper perspective, then, not all acts of stalkers are rejected or alarming, because their targets don’t perceive their motives as deviant or predatory. The overtures of stalkers, interpreted as normal courtship behaviors, may be invited or even welcomed by the unsuspecting.

Placed in proper perspective, then, not all acts of stalkers are rejected or alarming, because their targets don’t perceive their motives as deviant or predatory. The overtures of stalkers, interpreted as normal courtship behaviors, may be invited or even welcomed by the unsuspecting. courts by disordered personalities as stalkers ignite in them the need to clear their names, on which their livelihoods may depend (never mind their sanity); and their determination, which for obvious reasons may be obsessive, seemingly corroborates stalkers’ false allegations of stalking.

courts by disordered personalities as stalkers ignite in them the need to clear their names, on which their livelihoods may depend (never mind their sanity); and their determination, which for obvious reasons may be obsessive, seemingly corroborates stalkers’ false allegations of stalking.

Contemplating these statements should also make clear the all-but-impossible task that counteracting the fraudulent allegations of high-conflict people can pose, both because disordered personalities lie without compunction and because they’re intensely invested in domination, blaming, and punishment.

Contemplating these statements should also make clear the all-but-impossible task that counteracting the fraudulent allegations of high-conflict people can pose, both because disordered personalities lie without compunction and because they’re intensely invested in domination, blaming, and punishment. I’ve read Freud, Lacan, and some other abstruse psychology texts, because I was trained as a literary analyst, and psychological theories are sometimes used by textual critics as interpretive prisms. None of these equipped me, though, to understand the kind of person who would wantonly lie to police officers and judges, enlist others in smear campaigns, and/or otherwise engage in dedicatedly vicious misconduct.

I’ve read Freud, Lacan, and some other abstruse psychology texts, because I was trained as a literary analyst, and psychological theories are sometimes used by textual critics as interpretive prisms. None of these equipped me, though, to understand the kind of person who would wantonly lie to police officers and judges, enlist others in smear campaigns, and/or otherwise engage in dedicatedly vicious misconduct.

If you’ve been attacked serially by someone you trusted who’s abused legal process to hurt you, spread false rumors about you, made false allegations against you, and otherwise manipulated others to join in bullying you (possibly over a period spanning years and despite your reasonable attempts to settle the situation), your persecutor is an example of the high-conflict person to whom the epigraph refers, and understanding his or her motives may be of value to your self-protection.

If you’ve been attacked serially by someone you trusted who’s abused legal process to hurt you, spread false rumors about you, made false allegations against you, and otherwise manipulated others to join in bullying you (possibly over a period spanning years and despite your reasonable attempts to settle the situation), your persecutor is an example of the high-conflict person to whom the epigraph refers, and understanding his or her motives may be of value to your self-protection. Under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), our courts and police districts are awarded hefty

Under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), our courts and police districts are awarded hefty  Judicial process proceeds from rules first and facts second. Our entire system of law is based upon the principle of stare decisis, which says that what has previously been decided must be adhered to.

Judicial process proceeds from rules first and facts second. Our entire system of law is based upon the principle of stare decisis, which says that what has previously been decided must be adhered to. So enculturated has the belief that women are helpless victims become that no one recognizes that feminist political might is unrivaled—unrivaled—and it’s in the interest of preserving that political might and enhancing it that the belief that women are helpless victims is vigorously promulgated by the feminist establishment that should be promoting the idea that women aren’t helpless.

So enculturated has the belief that women are helpless victims become that no one recognizes that feminist political might is unrivaled—unrivaled—and it’s in the interest of preserving that political might and enhancing it that the belief that women are helpless victims is vigorously promulgated by the feminist establishment that should be promoting the idea that women aren’t helpless.