“Restraining orders give victims of domestic violence a tool to keep their abusers away or at least have them arrested if they come close. Anyone in a relationship with recent history of abuse can apply, and the order can be signed the same day.

“It gives victims the right to stay in the home and keep the kids. But the civil document relies on their abusers to respect the law.”

—“Are Restraining Orders False Security?” (USA Today)

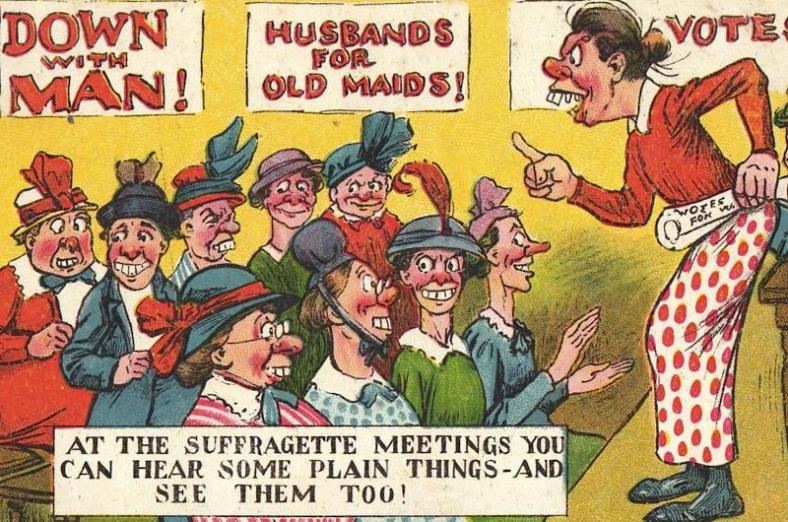

Reporters are often keen and eager detectives when there are two sides to a story, and they want to get to the bottom of things. When there aren’t clearly defined contestants with competing narratives, however, reporters are as prone as anyone else to swallow what they’re told.

The news story the epigraph was excerpted from was prompted by a recent murder in Oregon and explores the impotence of restraining orders, in particular to “stop bullets.” Just as shooting sprees inspire reporters to investigate gun legislation, murder victims who had applied for restraining orders that proved worthless inspire reporters to investigate restraining order policies. The presumption, always, is that the law failed.

The news story the epigraph was excerpted from was prompted by a recent murder in Oregon and explores the impotence of restraining orders, in particular to “stop bullets.” Just as shooting sprees inspire reporters to investigate gun legislation, murder victims who had applied for restraining orders that proved worthless inspire reporters to investigate restraining order policies. The presumption, always, is that the law failed.

The solution suggested by the story—the same solution that’s always suggested by such stories—is to beef up protocols and give the statutes more teeth.

What’s inevitably lost in considerations like this is that for every person who’s attacked or killed in spite of a restraining order, thousands, tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands of people face grave indignities and privations consequent to orders’ being used exploitatively (including public revilement, chronic harassment, criminal profiling, social alienation, and loss of employment, health, and access to kids, home, and property). This is a fact it seems journalists would only be given cause to confront if more victims of procedural abuse killed themselves.

Preferable, certainly, would be if reporters could be depended on to sniff out and censure injustice without anyone’s having to die.

Toward this end, this post encourages reporters to recognize what the quoted paragraphs that introduce it actually say. This is revealed by removing the obfuscating rhetoric. Replace the phrase victims of domestic violence with accusers, and replace their abusers with the accused.

Now consider the implications of the same paragraphs, slightly revised:

“Restraining orders give accusers a tool to keep the accused away or at least have them arrested if they come close. Anyone in a relationship…can apply, and the order can be signed the same day.

“It gives accusers the right to stay in the home and keep the kids….”

The mere substitution of factually accurate, unbiased labels changes the meaning of these paragraphs significantly, and brings their implications to the fore.

Now dare to think the unthinkable (as every factual analyst should) and replace the word accusers with the word liars and the phrase the accused with the phrase those lied about, and pare away a few more words.

“Restraining orders give liars a tool to keep those lied about away or have them arrested. Anyone in a relationship can apply, and the order can be signed the same day.

“It gives liars the right to stay in the home and keep the kids.”

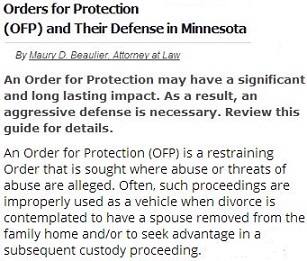

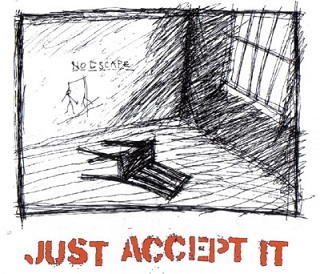

The same two paragraphs, reconceived, say that a restraining order can be got by lying to the court, can be used to have someone arrested without warrant based on the report of the liar, can be had in a single day (without the accused’s even being given prior notice of the proceedings), and can be used to gain immediate and sole entitlement to a place of residence and immediate and sole custody of children.

Appreciate that there are no (enforced) penalties for lying, and suddenly the motives and opportunity for fraud—particularly against a target of malice—become plain.

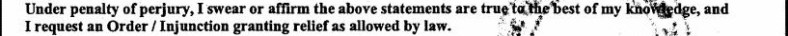

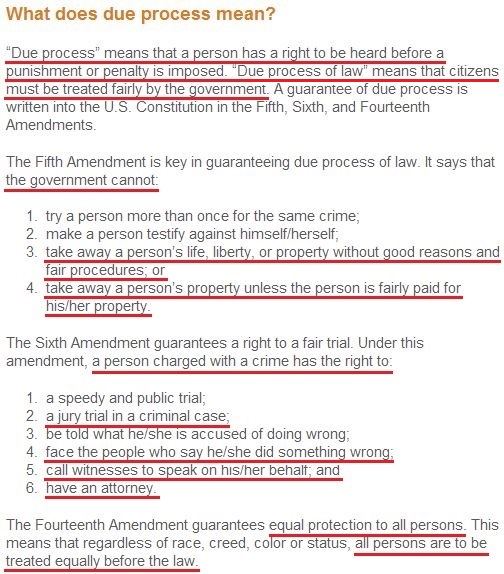

Appreciate further that allegations made by restraining order petitioners aren’t subject to the criminal standard (“proof beyond a reasonable doubt”). Restraining order trials are civil adjudications, not criminal ones. The “standard of proof” applied is “preponderance of the evidence,” which means no certain substantiation of allegations ranging from nuisance to sexual assault is required. Approval of a restraining order isn’t a (literal) finding of guilt, per se. No proof of anything must be established.

People, including journalists, only see what they hear.

The truth of how conveniently and urgently restraining orders avail themselves as tools of abuse is right under the noses of everyone who writes about them. It just gets obscured by loaded words (victims and abusers, for example) and the images they excite. Blindness to these words’ unexamined assumptions is further reinforced by the hysteria aroused by a (single) sensational act of violence.

Principal among these unexamined assumptions is that everyone who claims to be a victim is a victim (according to which belief everyone who claims to be a victim is treated as a victim by the court—which every false claimant dependably anticipates).

Observing this by using a story about a tragedy shouldn’t seem callous, because (1) it’s in the wake of tragedies like the one reported in the referenced story that hysteria runs highest and completely eclipses critical scrutiny, and (2) it’s tragedies like the one reported in the referenced story that show that restraining orders, besides being excellent tools to realize spiteful or avaricious intentions, aren’t any good at doing the one thing that’s said to justify them: averting violence.

On the contrary, the story reports:

“For some people it’s more dangerous [to get a restraining order],” said Kim Larson, director for Marion County District Attorney Victim Assistance Division. “Sometimes it makes people really angry, getting served with a restraining order.”

“For some people it’s more dangerous [to get a restraining order],” said Kim Larson, director for Marion County District Attorney Victim Assistance Division. “Sometimes it makes people really angry, getting served with a restraining order.”

This is especially true if the order is false. (Besides inspiring violent people to commit further violence, restraining orders may drive nonviolent people to lash out or even kill in desperation, particularly if they’ve been falsely accused, publicly excoriated, and deprived of all that gave their lives meaning.)

This isn’t rocket science. People lie, and when people lie about abuse, they do egregious and often irrevocable harm to those they falsely blame—who only very rarely kill themselves. No one looks beneath the surface, because they faithfully cleave to popular conceptions and reasonably assume that there are safeguards in place (due process and such) to ensure that allegations of abuse are properly vetted and substantiated.

Investigators shouldn’t assume.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

My ex-husband’s family just filed their second bogus restraining order against me to overturn custody of our 13-year-old. The first one, three years ago, I spent three months and $25,000 to fight, and got my son back. This one? I promised myself not to fight if they tried again, and I didn’t and lost today in court. They upheld the emergency order of protection and extended a restraining order against me for no contact with my own son for nothing I did at all—for two years. My son wants to be with them, so I’m not fighting. I just don’t want him to grow up thinking I did anything wrong and that’s why they took him from me. I don’t need to lose any more money and get fired from any more jobs trying to fight…. I’m done.

My ex-husband’s family just filed their second bogus restraining order against me to overturn custody of our 13-year-old. The first one, three years ago, I spent three months and $25,000 to fight, and got my son back. This one? I promised myself not to fight if they tried again, and I didn’t and lost today in court. They upheld the emergency order of protection and extended a restraining order against me for no contact with my own son for nothing I did at all—for two years. My son wants to be with them, so I’m not fighting. I just don’t want him to grow up thinking I did anything wrong and that’s why they took him from me. I don’t need to lose any more money and get fired from any more jobs trying to fight…. I’m done. Feminists are encouraged to respond to this mom’s story, whether with sympathy or criticism. The court process she’s a victim of isn’t one this writer condones. Let’s hear from some people who do condone it.

Feminists are encouraged to respond to this mom’s story, whether with sympathy or criticism. The court process she’s a victim of isn’t one this writer condones. Let’s hear from some people who do condone it.

On 15 March 2009 at 11.07pm: Hi there! How are you? I am lying in my bed and thinking…I miss you and miss having you in my life and I would love to have you back in it…. I do have a lot of issues, I know, and I suppose I am a difficult woman at times…. In the same breath, I could have made the biggest tit out of myself now, because you might have met someone else…. Deep down inside I hope you miss me as much as I miss you! […] I don’t want you to feel that I am pressurising you….

On 15 March 2009 at 11.07pm: Hi there! How are you? I am lying in my bed and thinking…I miss you and miss having you in my life and I would love to have you back in it…. I do have a lot of issues, I know, and I suppose I am a difficult woman at times…. In the same breath, I could have made the biggest tit out of myself now, because you might have met someone else…. Deep down inside I hope you miss me as much as I miss you! […] I don’t want you to feel that I am pressurising you…. A female respondent to the blog brought my attention to the three-year-old story out of Cape Town, South Africa from which the epigraph is excerpted. It’s about a man who was served with a domestic violence restraining order (later revised to a stalking protection order) petitioned by a woman he’d threatened to “un-friend” on Facebook and with whom he’d never had a domestic relationship (he says they had fatefully “kissed once or twice” during a “brief fling”). The order was apparently the tag-team brainchild of this woman, who would be called a stalker according to even the most forgiving standards, and another woman, an attorney the man had dated for six months.

A female respondent to the blog brought my attention to the three-year-old story out of Cape Town, South Africa from which the epigraph is excerpted. It’s about a man who was served with a domestic violence restraining order (later revised to a stalking protection order) petitioned by a woman he’d threatened to “un-friend” on Facebook and with whom he’d never had a domestic relationship (he says they had fatefully “kissed once or twice” during a “brief fling”). The order was apparently the tag-team brainchild of this woman, who would be called a stalker according to even the most forgiving standards, and another woman, an attorney the man had dated for six months.

Here are two recent headlines that caught my eye: “

Here are two recent headlines that caught my eye: “ Recognize that in these rare instances when perjury statutes are enforced, the motive is political impression management (government face-saving). Everyday claimants who lie to judges are never charged at all, because the victims of their lies (moms, dads,

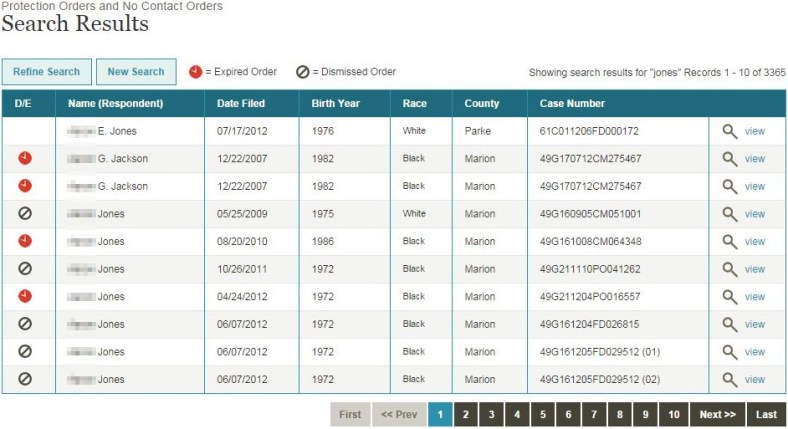

Recognize that in these rare instances when perjury statutes are enforced, the motive is political impression management (government face-saving). Everyday claimants who lie to judges are never charged at all, because the victims of their lies (moms, dads,  One of the thrusts of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) has been to establish public restraining order registries like those that identify sex offenders.

One of the thrusts of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) has been to establish public restraining order registries like those that identify sex offenders.

pay them money I didn’t even owe! This person was my babysitter, who is the most manipulative, money hungry witch. I just didn’t know it until now.

pay them money I didn’t even owe! This person was my babysitter, who is the most manipulative, money hungry witch. I just didn’t know it until now.

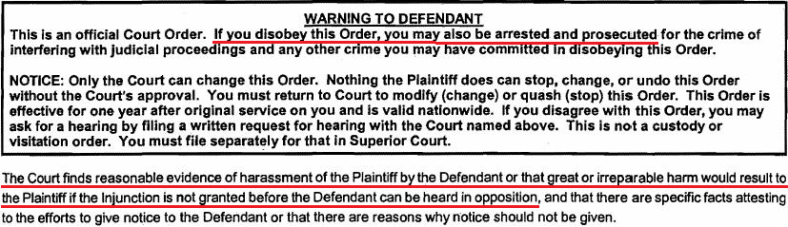

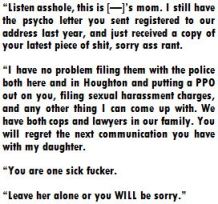

Appreciate that the court’s basis for issuing the document capped with the “Warning” pictured above is nothing more than some allegations from the order’s plaintiff, allegations scrawled on a form and typically made orally to a judge in four or five minutes.

Appreciate that the court’s basis for issuing the document capped with the “Warning” pictured above is nothing more than some allegations from the order’s plaintiff, allegations scrawled on a form and typically made orally to a judge in four or five minutes.

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

What isn’t appreciated by critics of various men’s rights advocacy groups is that these groups’ own criticisms are provoked by legal inequities that are inspired and reinforced by feminist groups and their socially networked loyalists. These feminist groups arrogate to themselves the championship of female causes, among them that of battered women. Feminists are the movers behind the “battered women’s movement.”

What isn’t appreciated by critics of various men’s rights advocacy groups is that these groups’ own criticisms are provoked by legal inequities that are inspired and reinforced by feminist groups and their socially networked loyalists. These feminist groups arrogate to themselves the championship of female causes, among them that of battered women. Feminists are the movers behind the “battered women’s movement.”

The professor carefully prefaces her points with phrases like “Researchers have noted,” which gives them the veneer of plausibility but ignores this obvious question: where do the loyalties of those “researchers” lie? The professor cites, for example, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s equation of SAVE Services with a hate group. An attentive survey of SAVE’s reportage, however, would suggest little correspondence. The professor doesn’t quote any of SAVE’s reports; she simply quotes an opposing group’s denunciation of them as being on a par with white supremacist propaganda.

The professor carefully prefaces her points with phrases like “Researchers have noted,” which gives them the veneer of plausibility but ignores this obvious question: where do the loyalties of those “researchers” lie? The professor cites, for example, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s equation of SAVE Services with a hate group. An attentive survey of SAVE’s reportage, however, would suggest little correspondence. The professor doesn’t quote any of SAVE’s reports; she simply quotes an opposing group’s denunciation of them as being on a par with white supremacist propaganda.

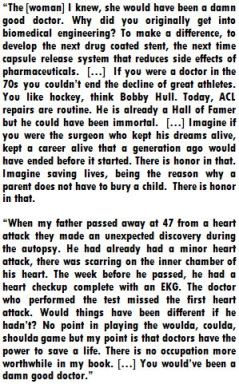

Grant Dossetto has a degree in finance he can’t use.

Grant Dossetto has a degree in finance he can’t use. Though his mother lived to see him earn his degree with honors in 2009, neither of Grant’s parents will ever know that their investment in their son’s success was betrayed or that his professional aspirations were dashed, because they’ve passed away.

Though his mother lived to see him earn his degree with honors in 2009, neither of Grant’s parents will ever know that their investment in their son’s success was betrayed or that his professional aspirations were dashed, because they’ve passed away. In Grant’s home state of Michigan, this qualifies as service. No copy of the order was ever provided to him.

In Grant’s home state of Michigan, this qualifies as service. No copy of the order was ever provided to him. No surprise, Grant has “suffered from severe depression that still surfaces at times now.” His case exemplifies the justice system’s willingness to compound the stresses of real exigencies like family crises with false exigencies like nonexistent danger.

No surprise, Grant has “suffered from severe depression that still surfaces at times now.” His case exemplifies the justice system’s willingness to compound the stresses of real exigencies like family crises with false exigencies like nonexistent danger.

The judge who issued the 2010 order, James Biernat, Sr., is famous for presiding over the “Comic Book Murder” case. It was big enough to make Dateline and the other true crime outlets. He overturned a guilty conviction from a jury and demanded a retrial. The action was extraordinary, held up on appeal by a split decision. The Macomb prosecutor publically rebuked him as being soft on crime. That made national news. All the cable outlets covered the second trial, which yielded the same result: guilty. He was rebuked by two dozen jurors, three appellate justices, and the prosecutor. It’s funny, if he had just given me a hearing, let alone a second, I truly believe a PPO would never have been issued.

The judge who issued the 2010 order, James Biernat, Sr., is famous for presiding over the “Comic Book Murder” case. It was big enough to make Dateline and the other true crime outlets. He overturned a guilty conviction from a jury and demanded a retrial. The action was extraordinary, held up on appeal by a split decision. The Macomb prosecutor publically rebuked him as being soft on crime. That made national news. All the cable outlets covered the second trial, which yielded the same result: guilty. He was rebuked by two dozen jurors, three appellate justices, and the prosecutor. It’s funny, if he had just given me a hearing, let alone a second, I truly believe a PPO would never have been issued.

Members of the legislative subcommittee referenced in The Courant article reportedly expect to improve their understanding of the flaws inherent in the restraining order process by taking a field trip. They plan “a ‘ride along’ with the representative of the state marshals on the panel…to learn more about how restraining orders are served.”

Members of the legislative subcommittee referenced in The Courant article reportedly expect to improve their understanding of the flaws inherent in the restraining order process by taking a field trip. They plan “a ‘ride along’ with the representative of the state marshals on the panel…to learn more about how restraining orders are served.”

It’s often reported by recipients of restraining orders that the cops and constables who serve them recognize they’re stigmatizing.

It’s often reported by recipients of restraining orders that the cops and constables who serve them recognize they’re stigmatizing. “Obscure public records” is how some officers of the court think of restraining orders. In the age of the Internet, there are no such things. Many judges are in their 60s and 70s, however, and scarcely know the first thing about the Internet, let alone Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. They’re still living in the days of mimeographs and microfiche.

“Obscure public records” is how some officers of the court think of restraining orders. In the age of the Internet, there are no such things. Many judges are in their 60s and 70s, however, and scarcely know the first thing about the Internet, let alone Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. They’re still living in the days of mimeographs and microfiche. A high school cheerleader whose dad is a former chief of police had a boyfriend her parents disapproved of. The girl says her parents “threw her out” because of him; her parents say she left because she didn’t want to abide by their rules.

A high school cheerleader whose dad is a former chief of police had a boyfriend her parents disapproved of. The girl says her parents “threw her out” because of him; her parents say she left because she didn’t want to abide by their rules. Here’s the reply the email elicited from ABC’s Bob Borzotta: “Hi Larry, I don’t seem to have heard further from her. Sounds like quite a situation….” Cursory validations like this one are the closest thing to solace that victims of chronic legal abuses can expect.

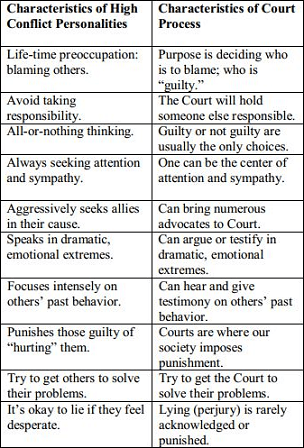

Here’s the reply the email elicited from ABC’s Bob Borzotta: “Hi Larry, I don’t seem to have heard further from her. Sounds like quite a situation….” Cursory validations like this one are the closest thing to solace that victims of chronic legal abuses can expect. The target of a high-conflict person is perpetually on the defensive, trying to recover his or her former life from the unrelenting grasp of a crank with an extreme (and often pathological) investment in eroding that life for self-aggrandizement and -gratification.

The target of a high-conflict person is perpetually on the defensive, trying to recover his or her former life from the unrelenting grasp of a crank with an extreme (and often pathological) investment in eroding that life for self-aggrandizement and -gratification. The ease with which a restraining order is obtained encourages outrageous defamations like these (Larry’s neighbor has sworn out two). Once a high-conflict person sees how readily

The ease with which a restraining order is obtained encourages outrageous defamations like these (Larry’s neighbor has sworn out two). Once a high-conflict person sees how readily

In the spring of 2011, she had been converting her home to a sort of boarding house and brought in tenants, and [between] them they had two cats that constantly prowled, especially the tenant’s. What became very irksome to me was the tenant’s cat creeping into our yard and killing our baby birds, which we always looked forward to in the spring. And the minute I brought it up with her, she pitched a fit, and so did the tenant. So for the first two months of baby bird season, [their] cats killed all our fledglings and the mother songbirds—wrens, cardinals, robins, mockingbirds, towhees, mourning doves, even the hummingbirds, just wiped them out. I finally got in touch with our Animal Services officers, but by that time bird season was over with, and you know something, [she] began going about telling neighbors that I was a disbarred lawyer (a particularly nasty slander). One thing led to another, and finally the tenant with the marauding cat moved away, but the irreparable damage was done, and all through the summer I had been warned by other neighbors that the neighbor from hell was plotting revenge.

In the spring of 2011, she had been converting her home to a sort of boarding house and brought in tenants, and [between] them they had two cats that constantly prowled, especially the tenant’s. What became very irksome to me was the tenant’s cat creeping into our yard and killing our baby birds, which we always looked forward to in the spring. And the minute I brought it up with her, she pitched a fit, and so did the tenant. So for the first two months of baby bird season, [their] cats killed all our fledglings and the mother songbirds—wrens, cardinals, robins, mockingbirds, towhees, mourning doves, even the hummingbirds, just wiped them out. I finally got in touch with our Animal Services officers, but by that time bird season was over with, and you know something, [she] began going about telling neighbors that I was a disbarred lawyer (a particularly nasty slander). One thing led to another, and finally the tenant with the marauding cat moved away, but the irreparable damage was done, and all through the summer I had been warned by other neighbors that the neighbor from hell was plotting revenge.

Its introduction, at least, was gripping to read: “At what was billed as the first annual international conference on men’s issues, feminists were ruining everything.” I was keen to hear about how the meeting was disrupted by a mob of angry women swinging truncheons.

Its introduction, at least, was gripping to read: “At what was billed as the first annual international conference on men’s issues, feminists were ruining everything.” I was keen to hear about how the meeting was disrupted by a mob of angry women swinging truncheons. I’m sympathetic to men’s plaints about legal mockeries that trash lives, including those of children, so I found the MSNBC coverage offensively yellow-tinged in more senses than one, but I’m not what feminists call an MRA or “men’s rights activist.” I don’t think men need any rights the Constitution doesn’t already promise them. What they need is for their government to recognize and honor those rights. The objection to feminism is that it has induced the state to act in wanton violation of citizens’ civil entitlements—not just men’s, but women’s, too.

I’m sympathetic to men’s plaints about legal mockeries that trash lives, including those of children, so I found the MSNBC coverage offensively yellow-tinged in more senses than one, but I’m not what feminists call an MRA or “men’s rights activist.” I don’t think men need any rights the Constitution doesn’t already promise them. What they need is for their government to recognize and honor those rights. The objection to feminism is that it has induced the state to act in wanton violation of citizens’ civil entitlements—not just men’s, but women’s, too. To illustrate, take the

To illustrate, take the  Women I’ve corresponded with in the three years I’ve maintained this blog have reported being stripped of their dignity and good repute, their livelihoods, their homes and possessions, and even their children according to prejudicial laws and court processes that are feminist handiworks. These laws and processes favor plaintiffs, who are typically women, so their prejudices are favored by feminists. Feminists decry inequality when it’s non-advantageous. They’re otherwise cool with it. What’s more, when victims of the cause’s interests are women, those victims are just as indifferently shrugged off—as “casualties of war,” perhaps.

Women I’ve corresponded with in the three years I’ve maintained this blog have reported being stripped of their dignity and good repute, their livelihoods, their homes and possessions, and even their children according to prejudicial laws and court processes that are feminist handiworks. These laws and processes favor plaintiffs, who are typically women, so their prejudices are favored by feminists. Feminists decry inequality when it’s non-advantageous. They’re otherwise cool with it. What’s more, when victims of the cause’s interests are women, those victims are just as indifferently shrugged off—as “casualties of war,” perhaps. “

“ A false restraining order litigant with a malicious yen may leave a courthouse shortly after entering it having gained sole entitlement to a residence, attendant properties, and children, possibly while displacing blame from him- or herself for misconduct, and having enjoyed the reward of an authority figure’s undivided attention won at the expense of his or her victim.

A false restraining order litigant with a malicious yen may leave a courthouse shortly after entering it having gained sole entitlement to a residence, attendant properties, and children, possibly while displacing blame from him- or herself for misconduct, and having enjoyed the reward of an authority figure’s undivided attention won at the expense of his or her victim.

“

“ The lawyers quoted by reporter, what’s more, refer to criminal cases in which sexual abuse is alleged and, consequently, in which the accused are afforded attorney representation.

The lawyers quoted by reporter, what’s more, refer to criminal cases in which sexual abuse is alleged and, consequently, in which the accused are afforded attorney representation.

Faith in the conceit that restraining orders are minor impingements on defendants’ lives depends on accepting that being falsely, publically, and permanently labeled a stalker or batterer, for example, shouldn’t interfere with a person’s comfort, equanimity, or ability to realize his or her dreams. Such faith is founded, in other words, on the fantastical belief that wrongful vilification won’t exercise a detrimental influence on a person’s mental state, won’t affect his or her familial and social relationships, won’t negatively impact his or her employment and employability, etc.

Faith in the conceit that restraining orders are minor impingements on defendants’ lives depends on accepting that being falsely, publically, and permanently labeled a stalker or batterer, for example, shouldn’t interfere with a person’s comfort, equanimity, or ability to realize his or her dreams. Such faith is founded, in other words, on the fantastical belief that wrongful vilification won’t exercise a detrimental influence on a person’s mental state, won’t affect his or her familial and social relationships, won’t negatively impact his or her employment and employability, etc. As attorneys and

As attorneys and

Plainly restraining orders have put no dent in the problem. What’s more, it’s possible they’ve made it worse.

Plainly restraining orders have put no dent in the problem. What’s more, it’s possible they’ve made it worse. Feminism doesn’t appeal to or cultivate sympathy; it largely strives to chastise and dominate, which can only foster misogyny.

Feminism doesn’t appeal to or cultivate sympathy; it largely strives to chastise and dominate, which can only foster misogyny. On balance, the curative value of restraining orders is null if not negative. Per capita, that is, they do more harm than good. And the impact of each instance of abuse of power is chain-reactive, because every victim has relatives and friends who may be jarred by its reverberations.

On balance, the curative value of restraining orders is null if not negative. Per capita, that is, they do more harm than good. And the impact of each instance of abuse of power is chain-reactive, because every victim has relatives and friends who may be jarred by its reverberations.

tenets of law, like impartiality, diligent deliberation, and

tenets of law, like impartiality, diligent deliberation, and

I’ve written before about “

I’ve written before about “

A defendant is deprived of liberty and often property, besides, without compensation and in accordance with manifestly unfair procedures concluded in minutes =

A defendant is deprived of liberty and often property, besides, without compensation and in accordance with manifestly unfair procedures concluded in minutes =