The ambition of this post, an intermission between considerations of graver subjects, is to dispel restraining order defendants’ faith in the value of “truth.” Defendants are led to believe that if they’re truthful in the defiance of lies or hyped allegations, all will turn out as it should. But truth is a false idol that answers no prayers.

If you haven’t yet had to swear this oath, you’ve heard it before on TV: “Do you swear to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth?” (Sometimes God and the word solemnly are thrown in for emphasis…maybe to suggest you’ll be struck by lightning if you distort the facts or omit any.)

The significance of this courtroom ritual is none, and taking it literally is for chumps.

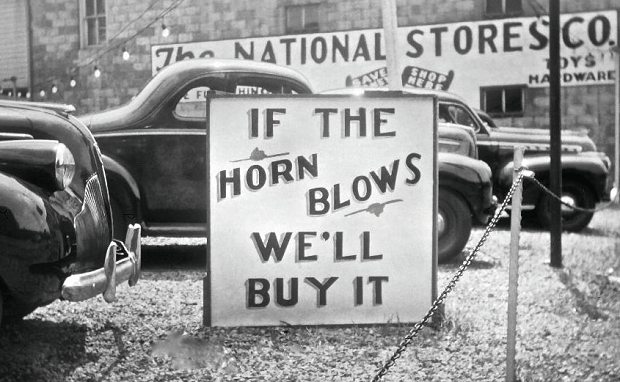

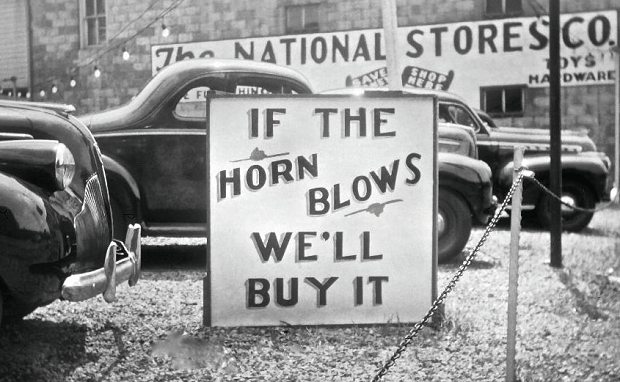

Civil trials, especially the kind this blog concerns, do not weigh “truth”; they weigh testimony, along with evidence as it’s represented (in procedures that may span minutes only). The savvy defendant will think in terms of economics and marketing. “Truth” has no inherent value to a defense. Unless it conclusively proves something you want to prove, it’s totally worthless. Worse, it may distract and dilute the potency of what you’re trying to sell. Facts, besides, may not tell the truth. The word truth is a trap for the naïve.

What wins cases are successful representations, ones that work the desired effect (i.e., what wins is salesmanship not scrupulous reporting).

While the court asks for honesty, it doesn’t reward it. It’s what you say and how you say it that counts, not “the truth.” God isn’t the judge; a man or woman is, and his or her favor goes to the person who gives the most compelling presentation (i.e., sales pitch).

Why do lying plaintiffs win? They win because their representations were persuasive. Did they tell “the whole truth and nothing but”? They may have told none at all. (Restraining orders have reportedly been obtained by people using assumed names; they didn’t even tell the truth of who they were.)

What do cunning attorneys who represent lying clients (or any clients) do? They tell only those truths that support their stories…and no others. (They may lie, also—and vigorously.)

The fastidious defendant who finicks over every detail, who backpedals and carefully qualifies his statements (in the interest of complete and accurate disclosure), and who otherwise invests his or her trust in “the truth” grossly misperceives the nature of process.

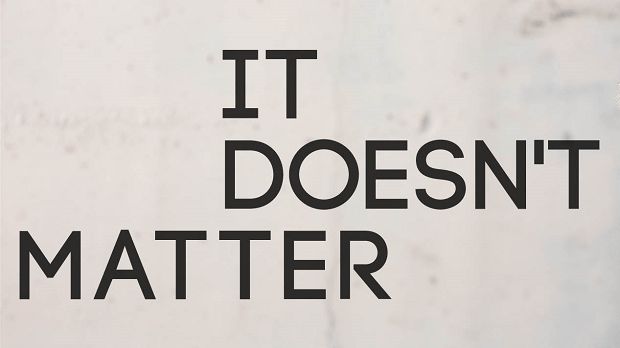

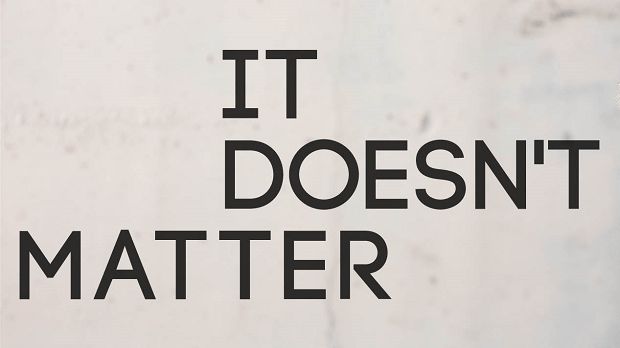

Representations win court contests, not “the truth.” The truth doesn’t matter.

~ EPILOG ~

A few months ago, the writer spoke for an hour or so with a 30-something man who said he was an obsessive-compulsive. He had written that he was “starting to go downhill really fast” and needed help. “I will try to eventually explain,” he began, “but there’s such a long history of what happened.”

What he explained was that he’d been bullied by a woman many years prior, while they were in high school, and had been haunted and galled by the abuse ever since. He said she had tried to coerce him to have sex with a friend of hers, that he had refused, and that she had spitefully urged some guys to rough him up (one of them would later be convicted of murder, so this wasn’t bush league bullying). She had also greeted him with a sneer whenever they met after that, and flipped him the bird and yelled “Fuck you!” at him as he passed by. He had tried to reach an accord but had only been mocked. He said he never used to stand up for himself and was sick of turning the other cheek.

He impulsively ventilated rage that he had bottled for 20 years by calling the cell of the woman’s husband and leaving her a voicemail that called her a “rude, mean bitch” and that ended with a string of “Fuck you!”s. That was pretty much the extent of it, but he was handily represented as a stalker.

He wanted to know what pointers I could offer that might aid him in his defense against a restraining order petitioned by a woman who claimed to have no memory of the events he described and whose stepmother, he said, was a former lawyer who had prosecuted cases before the state supreme court and was, besides, the director of a “domestic abuse and physical violence organization.”

Yeah.

I repeatedly impressed upon him that reciting a history that spanned decades wasn’t likely to move a judge to anything but a yawn (or a rebuke) and that he should consider how to frame his story to put himself in the most favorable light, for example, by updating the context (and abandoning a rigidly chronological narrative).

Each time I interrupted, he said he understood and then recommenced his story, which stretched back to his anguished childhood. He was very earnest and conscientious, and continually paused and qualified his remarks with “Granted, I….” It was important to him, he said, to tell his “heart’s truth” (i.e., the “whole truth”). He wanted someone to sympathize, and I did. But I knew a judge would not.

I never heard from him again.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

It’s hard not to hate judges who issue rulings that may be based on misrepresentations or outright fraud when those rulings (indefinitely) impute criminal behavior or intentions to defendants, may set defendants up for

It’s hard not to hate judges who issue rulings that may be based on misrepresentations or outright fraud when those rulings (indefinitely) impute criminal behavior or intentions to defendants, may set defendants up for

The account below was recently submitted as a comment to

The account below was recently submitted as a comment to  Perusing the trial transcript of a North Carolina man, former attorney

Perusing the trial transcript of a North Carolina man, former attorney