People falsely alleged to be abusers on restraining order petitions, particularly men, are treated like brutes, sex offenders, and scum by officers of the court and its staff, besides by authorities and any number of others. Some report their own relatives remain suspicious—often based merely on finger-pointing that’s validated by some judge in a few-minute procedure (and that’s when relatives aren’t the ones making the false allegations).

People falsely alleged to be abusers on restraining order petitions, particularly men, are treated like brutes, sex offenders, and scum by officers of the court and its staff, besides by authorities and any number of others. Some report their own relatives remain suspicious—often based merely on finger-pointing that’s validated by some judge in a few-minute procedure (and that’s when relatives aren’t the ones making the false allegations).

The social alienation and emotional distress felt by the falsely accused may be both extreme and persistent.

The urge to credit accusations of abuse has been sharpened to a reflex in recent decades by feminist propaganda and its ill begot progeny, the Violence Against Women Act. No one thinks twice about it.

Using four-letter words in court is strictly policed. Even judges can’t do it without risking censure. Falsely implicating someone, however, as a stalker, for example, or a child molester—that isn’t policed at all. Commerce in lies, whether by accusers, their representatives, or even judges themselves is unregulated. No one is answerable for sh* s/he makes up.

Accordingly, false allegations and fraud are rewarding and therefore commonplace.

It should be noted that false allegations and fraud can be distinctly different. For example, David Letterman famously had a restraining order petitioned against him by a woman who was seemingly convinced he was communicating to her through her TV, and her interpretations of his “coded messages” probably were genuinely oppressive to her. David Letterman lived in another state, had never met her, and assuredly had no idea who she was. Her allegations of misconduct weren’t true, but they weren’t intended to mislead (and the fact that they did mislead a judge into signing off on her petition only underscores the complete absence of judicial responsibility in this legal arena).

Fraud, in contrast, is manipulative and deceptive by design. It occurs when an accuser intentionally lies (or spins the facts) to give a false impression and steer a judge toward a wrong conclusion that serves the interests of the fraudster.

Regardless, though, of whether false allegations are made knowingly or unknowingly, they’re rarely discerned as false by the court, are seldom acknowledged as false even if recognized as such, and are always destructive when treated as real, urgent, and true, which they commonly are.

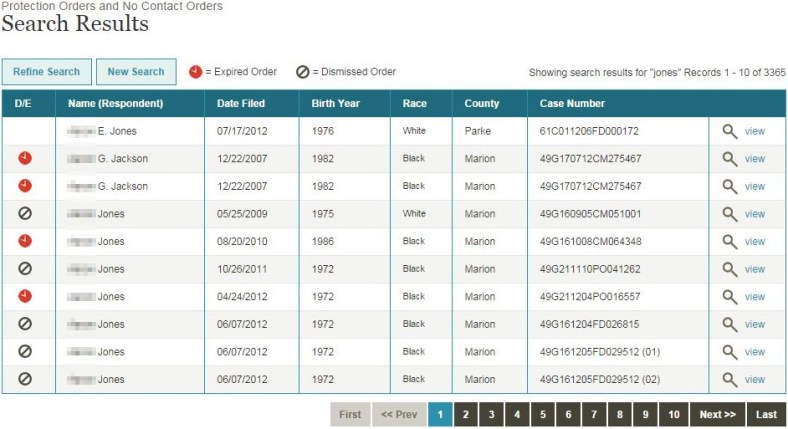

The falsely accused (often private citizens who’ve never had a prior brush with the law) are publicly humiliated and shamed, which by itself is predictably traumatizing. They are besides invariably (and indefinitely) entered into police databases, both local and national, and may be entered into one or more domestic violence registries, too (also indefinitely). These facts pop up on background checks, and defendants in some states may even appear in registries accessible by anyone (including friends, neighbors, family members, boy- and girlfriends, employers, colleagues, students, patients, and/or clients).

This costs the falsely accused leases, loans, and jobs (being turned down for which, of course, aggravates the gnawing indignity and outrage they already feel). Those falsely accused of domestic violence may further be prohibited from attending school functions or working with or around children (permanently). Defendants of false restraining orders may besides be barred from their homes, children, assets, and possessions. Some (including salaried, professional men and women) are left ostracized and destitute. Retirees report having to live out of their cars.

This, remember, is the result of someone’s lodging a superficial complaint against them in a procedure that only requires that the accuser fill out some paperwork and briefly talk to a judge. A successful fraud may be based on nothing more substantive, in fact, than five “magic” words: “I’m afraid for my life” (which can be directed against anyone: a friend, a neighbor, an intimate, a spouse, a relative, a coworker—even a TV celebrity their speaker has never met).

This incantation takes a little over a second to utter (and its speaker, who can be a criminal or a mental case, need not even live in the same state as the accused).

Accordingly, people’s names and lives are trashed—and no surprise if they become unhinged. (Those five “magic” words, what’s more, may be uttered by the actual abusers in relationships to conceal their own misconduct and redirect blame. That includes, for example, stalkers. Those “magic” words may also be used to cover up any nature of other misbehavior, including criminal. They instantly discredit anything the accused might say about their speakers.)

The prescribed course of action to redress slanders and libels is a defamation suit, but allegations of defamation brought by those falsely accused on restraining orders or in related prosecutions are typically discounted by the court. Perjury (lying to the court) can’t be prosecuted by a private litigant (only by the district attorney’s office, which never does), and those who allege defamation are typically told the court has already ruled on the factualness of the restraining order petitioner’s testimony and that it can’t be reviewed (the facts may not even be reviewed by appellate judges, who may only consider whether the conduct of the previous judge demonstrated “clear abuse of discretion”). The plaintiff’s testimony, they’re told, is a res judicata—an already “decided thing.” (Never mind that docket time dedicated to the formation of that “decision” may literally have been a couple of minutes.)

So…slanders and libels made by abuse of court process aren’t actionable, slanders and libels that completely sunder the lives of the wrongly accused, who can’t even get them expunged from their records to simply reset their fractured lives to zero.

So…slanders and libels made by abuse of court process aren’t actionable, slanders and libels that completely sunder the lives of the wrongly accused, who can’t even get them expunged from their records to simply reset their fractured lives to zero.

Such slanders and libels may include false allegations of stalking, physical or sexual aggression, assault, child abuse, or even rape. In the eyes of the court, someone’s being falsely implicated as a monster, publicly and for life, is no biggie.

In contrast, it was reported last month that the court awarded a Kansas woman $1,000,000 in a defamation suit brought against a radio station that falsely called her a “porn star.”

When violated people speak of legal inequities, this exemplifies what they’re talking about: Falsely and publicly implicating someone as a sex offender is fine and no grounds for complaint in the eyes of the justice system, but for the act of falsely and publicly calling someone a mere sex performer, someone may be fined a million bucks.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

One of the thrusts of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) has been to establish public restraining order registries like those that identify sex offenders.

One of the thrusts of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) has been to establish public restraining order registries like those that identify sex offenders.

Victims of false allegations made on restraining orders may be labeled “stalker,” “batterer,” “sicko,” “sexual harasser,” “child-abuser,” “whore,” or even “rapist”—publicly and permanently—by accusers whose sole motive is to brutalize. And agents of these victims’ own government(s) arbitrarily authorize this bullying and may baselessly and basely participate in it, compounding the injury exponentially.

Victims of false allegations made on restraining orders may be labeled “stalker,” “batterer,” “sicko,” “sexual harasser,” “child-abuser,” “whore,” or even “rapist”—publicly and permanently—by accusers whose sole motive is to brutalize. And agents of these victims’ own government(s) arbitrarily authorize this bullying and may baselessly and basely participate in it, compounding the injury exponentially.

Lawyers and judges I’ve talked to readily own their disenchantment with restraining order policy and don’t hesitate to acknowledge its malodor. It’s very rare, though, to find a quotation in print from an officer of the court that says as much. Job security is as important to them as it is to the next guy, and restraining orders are a political hot potato, because the feminist lobby is a powerful one and one that’s not distinguished for its temperateness or receptiveness to compromise or criticism.

Lawyers and judges I’ve talked to readily own their disenchantment with restraining order policy and don’t hesitate to acknowledge its malodor. It’s very rare, though, to find a quotation in print from an officer of the court that says as much. Job security is as important to them as it is to the next guy, and restraining orders are a political hot potato, because the feminist lobby is a powerful one and one that’s not distinguished for its temperateness or receptiveness to compromise or criticism.