Someone writes (in reply to an earlier commenter): “I too am a victim of a false order of protection and have the same judge. My story is an unbelievable loss of rights with no possible outcome of justice. As I am fearful that publicly telling my story would result in retribution from the judge, I must stay quiet until after I can get out of the court system.”

In the year or so that I’ve maintained this blog, it has received thousands of queries from people abused by restraining orders but considerably fewer actual comments from victims. Most of these comments are anonymous, and many victims seeking answers or consolation have instead emailed me to avoid subjecting themselves to further public scrutiny—understandably. They’re wounded, humiliated, and intimidated and have had it impressed upon them by the state that they if they don’t shut up they’ll be locked up (or suffer more permanent privations).

The restraining order process is sustained on shame and fear and perpetuated because of its political value not its social value, which is dubious at best. The agents of its perpetuation, the courts, are very effective at subduing resistance. Defendants are publicly condemned and threatened with police interference and further forfeitures of rights, and are saddled with allegations that make them afraid besides of social recrimination and rejection—even if those allegations are fraudulent. Avenues of relief are narrow and by and large only available to defendants of means, who, if they prevail, are glad to put the ordeal behind them and move on. The rest are put to flight. And so it goes…on.

First Amendment. Amendment to U.S. Constitution guaranteeing basic freedoms of speech, religion, press, and assembly and the right to petition the government for redress of grievances. The various freedoms and rights protected by the First Amendment have been held applicable to the states through the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (Black’s Law Dictionary, sixth ed.).

Due process clause. Two such clauses are found in the U.S. Constitution, one in the [Fifth] Amendment pertaining to the federal government, the other in the [Fourteenth] Amendment which protects persons from state actions. There are two aspects: procedural, in which a person is guaranteed fair procedures and substantive which protects a person’s property from unfair governmental interference or taking. Similar clauses are in most state constitutions. See Due process of law (Black’s Law Dictionary, sixth ed.).

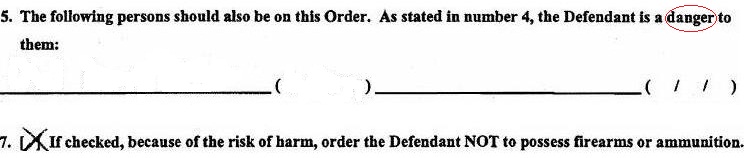

Glaring to anyone who peruses these entries in Black’s Law Dictionary and who’s been put through the restraining order wringer is that the process flouts the very principles on which our legal system was established (when I recall one of the judges in my own case referring to his courtroom as “the last bastion of civilization,” I don’t know whether to laugh or cry). It mocks the guarantee of fair procedures and the protection of a person’s property from unfair governmental interference or seizure—and it does a pretty decent job of convincing defendants that if they complain about it they’ll go from the frying pan into the fire. (For those who don’t have an intimate familiarity with the process, a restraining order case may receive no more than 10 minutes of deliberation from a judge—without ever meeting or hearing from the defendant—and even if appealed, no more than 20 or 30 minutes. That’s minutes. On allegations that often include stalking, battery, or violent threat; that may result in a defendant’s being denied access to home, property, family, and assets, and/or forfeiting his or her job and/or freedom; and that are publicly accessible and may be indefinitely stamped on a defendant’s record. It takes a judge many times longer to digest a meal than a restraining order case.)

If you’re a restraining order defendant, recognize these facts: (1) no matter what truth there is to allegations made against you in a restraining order, your civil rights have been violated by the state (all restraining order defendants are blindsided if not railroaded); (2) the restraining order process’s being constitutionally unsupportable makes it unworthy of respect; and (3) impressions by menacing rhetoric notwithstanding, you have every right to challenge the legitimacy of an unfair procedure (in fact, doing so makes you the last bastion of civilization).

Reject the impulse the process inspires to withdraw and hide. Seek counsel (consult with an attorney—or three—even if you can’t afford to employ one). Get information. Harry court clerks until your questions are answered. Ask others for help in the form of character and witness testimony and affidavits, advice, legwork, or just moral support. Get familiar with a local law library (university librarians, in particular, are very helpful). Request a postponement from the court if you need more time to prepare a defense. File a motion to see a judge if your appeal is normally conducted in writing only. Be assertive. Make the plaintiff work for it.

The restraining order process is a specter that feeds on fear. Switch on the light. Remember that as horrible as the accusations against you may seem or feel to you, they’re not likely to be credited by those who know you—especially if those accusations are completely unfounded. And chances are lawyers you explain them to will yawn rather than wag their fingers at you. They’ve heard it all before and know to take allegations made in restraining orders with a shaker of salt. So don’t hesitate to reach out, particularly if the case against you is trumped up. The last thing you want to do is give it credibility by behaving as though it’s legitimate. Don’t violate a restraining order but do resist its tearing your life apart.

And if one has compromised your life and you’re “out of the court system” as the commenter in the epigraph awaits becoming, recognize that your freedom of speech is sacrosanct. This nation was founded on the blood of men who died to guarantee your right to express yourself.

This travesty, the restraining order process, is a breach of the contract between the state and its citizens, and it endures because defendants feel impotent, helpless, and vulnerable (even after their cases are long concluded). This is how you’re meant to feel, and the effectiveness of this emotional coercion is what ensures that the cogs of the meat grinder stay greased.

Don’t give ’em the satisfaction.

Copyright © 2012 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.) My friend Annie has been pulling her hair out and medicating herself to sleep (I’ve done the same since I was falsely accused years ago—god bless Benadryl!). She’s even had to resort to applying to the mayor, a former colleague, for a character reference: this to combat allegations that wouldn’t bear up under the scrutiny of a schnauzer. If she successfully prosecutes her appeal, she’ll have had to forfeit enough money for a decent used car, will be remembered for having unsavory associates, and will be subject to the idle speculations aroused by the phrase restraining order. And even if she’s exculpated in the minds of everyone she knows and has had to share this with, the stigma will linger with her in her own psyche (which will itself be only a shadow of what she’ll have to live with if the judge finds for her accuser). This public shaming promotes alienation, bitterness, and depression (besides an abiding distrust of government).

My friend Annie has been pulling her hair out and medicating herself to sleep (I’ve done the same since I was falsely accused years ago—god bless Benadryl!). She’s even had to resort to applying to the mayor, a former colleague, for a character reference: this to combat allegations that wouldn’t bear up under the scrutiny of a schnauzer. If she successfully prosecutes her appeal, she’ll have had to forfeit enough money for a decent used car, will be remembered for having unsavory associates, and will be subject to the idle speculations aroused by the phrase restraining order. And even if she’s exculpated in the minds of everyone she knows and has had to share this with, the stigma will linger with her in her own psyche (which will itself be only a shadow of what she’ll have to live with if the judge finds for her accuser). This public shaming promotes alienation, bitterness, and depression (besides an abiding distrust of government).