“[V]icious energy and ugliness is there beneath the fervor of our new reckoning, adeptly disguised as exhilarating social change. It feels as if the feminist moment is, at times, providing cover for vindictiveness and personal vendettas and office politics and garden-variety disappointment, that what we think of as purely positive social change is also, for some, blood sport.”

—NYU Prof. Katie Roiphe

A preliminary, superfluous observation: Prof. Roiphe is right. The only valid criticism of her perspectives is that what she perceives as new and alarming isn’t new but only newly visible because of social media.

A recent post considered some measured criticisms of an essay of hers, “The Other Whisper Network: How Twitter feminism is bad for women,” which was published a couple of months ago in Harper’s. Jonathan Chait of New York Magazine quibbled, “Katie Roiphe Is Right About Twitter Feminism and Wrong About #MeToo.”

Underscoring the absurdity of the “dialogue,” a week before Mr. Chait said Prof. Roiphe was right about Twitter feminism, Sarah Jones of The New Republic, where Mr. Chait worked for 16 years, pronounced: “There’s no such thing as Twitter Feminism.”

Other responses, instancing dramatic irony that reinforces Prof. Roiphe’s points about mainstream feminism’s knee-jerk intolerance and conformity policing:

- “The Twisted, Confusing Logic of Katie Roiphe’s #MeToo Essay in Harper’s” (Christina Cauterucci, Slate, in a column called “Brow Beat”)

- “‘Twitter Feminists to Katie Roiphe: This Essay Is Not Very Good—Also ‘Staggeringly Boring,’ ‘Dishonest,’ and ‘Misdirected’” (Emily Temple, Literary Hub)

- “‘Shitty Media Men’ and Katie Roiphe’s Irresponsible Cruelty” (Erin Gloria Ryan, former managing editor of Jezebel, in The Daily Beast, where she reports a feminist named “Nicole Cliffe offered to pay writers who had pieces lined up with Harper’s to pull their work”)

The reactions themselves are protracted tweets and creepily insular and incestuous. There’s no evidence their authors read anything but one another and those they consider influential blasphemers, like Prof. Roiphe, who is probably considered a gender-betrayer. The repeated reference to Prof. Roiphe’s essay as “anticipated” suggests a throng of rabid feminist meat merchants impatiently whetting their knives—in lockstep accord with Prof. Roiphe’s criticism of their leap to prejudge and their “vicious energy.”

To any sane reader, Prof. Roiphe’s essay isn’t even edgy. Consider a point like this, for instance:

[C]onnecting condescending men and rapists as part of the same wellspring of male contempt for women…renders the idea of proportion irrelevant.

Or:

The need to differentiate between smaller offenses and assault is not interesting to a certain breed of Twitter feminist; it makes them impatient, suspicious. The deeper attitude toward due process is: don’t bother me with trifles!

The scandal is that statement of the obvious is felt to be a daring act of defiance. Prof. Roiphe quotes members of a “new whisper network” who “fear varieties of retribution (Twitter rage, damage to their reputations, professional repercussions, and vitriol from friends) for speaking out” about “the weird energy behind [the #MeToo] movement.” Prof. Roiphe says:

Before the piece was even finished, let alone published, people were calling me “pro-rape,” “human scum,” a “harridan,” a “monster out of Stephen King’s ‘IT,’?” a “ghoul,” a “bitch,” and a “garbage person”—all because of a rumor that I was planning to name the creator of the so-called Shitty Media Men list.

Her piece centers around a list of professional media men alleged to be miscreants, a list that one of her “whisperers” describes as “Maoist.” The celebrity bellwethers of the #MeToo movement, who were collectively named Person of the Year by Time Magazine, were extolled as “silence breakers.” For doing the same thing unpopularly, Prof. Roiphe is derogated “scum.”

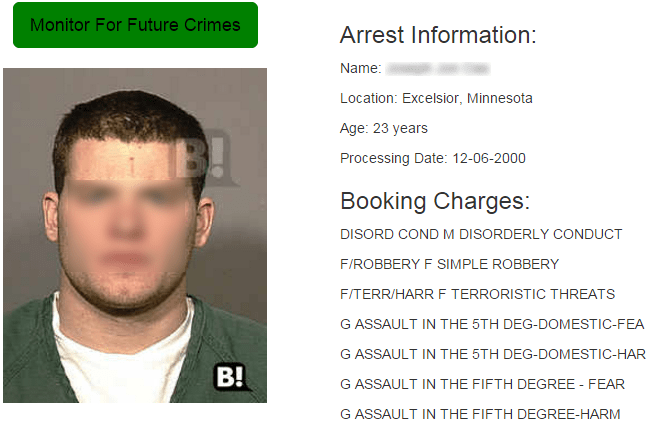

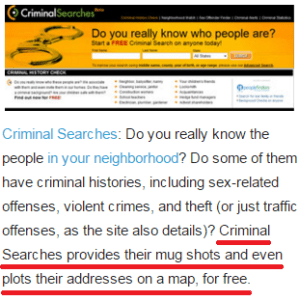

Noteworthy is the perception by a journalism professor that this sort of feminist list-making is novel when it has been the feminist m.o. for years, maybe decades. The push under the Violence Against Women Act, or VAWA (advent 1994), has been to have anyone who is accused, in civil court no less, entered into permanent public registries, even in cases if the allegations were later dismissed. (This is actually a contractually stipulated demand made of states in return for massive federal grants.) Lawmakers who have opposed renewal of VAWA have been publicly “outed” the same way.

Jonathan Chait, mentioned in the introduction to this post, besides in an earlier one, calls Prof. Roiphe’s essay “alternatingly brilliant and incoherent.” The essay is ranging, but there’s nothing incoherent about it.

Its sole fault is its assumption that only still waters run deep. Neither feminists’ “great, unmanageable anger” nor its unseen impacts are new.

Copyright © 2018 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*Toward the end of her essay, in a description of a conversation with a friend, Prof. Roiphe relates a reaction she had that exactly mirrors how civil court allegations of abuse are received by judges and adjudicated: “[A]s she was talking, I was completely drawn in. I found myself wanting to say something to please her. The outrage grew and expanded and exhilarated us. It was as though we weren’t talking about [an alleged abuser] anymore, we were talking about all the things we have ever been angry about…. I felt as though I were joining a club, felt a warming sense of social justice, felt that this was a weighty, important thing we were engaging in.” This response, which Prof. Roiphe says caused her to feel remorseful afterwards, is the same one that has been drilled into judges for decades thanks to feminist politicking. Why it requires a blogger to make such a connection is baffling.