A recent respondent to this blog proposed that I look into motions to the court that restraining order defendants (or past defendants) might wish to make. He indicated that he managed to have an injunction that was filed against him vacated by presenting himself as more credible than the plaintiff in the case and that various motions he filed were instrumental to his success.

Motions endeavor to move the court to take a requested action (for example, to grant you more time to respond to or to vacate the case against you). A motion may be made orally (during a hearing, for example): “If it please the court, the defendant moves that the plaintiff’s restraining order be vacated on the basis that….” Or it may be made in a written brief submitted to a clerk to relay to the judge. Examples of various kinds of motions can be found on the Internet if you search diligently enough, and their language can be used as models for motions you may wish to file. The caption (heading) on your written brief(s) might look something like this:

Or it might be formatted very differently. Find an example of a brief submitted to your local court to use as a template.

In a motion you filed to respond to or oppose a restraining order, you would identify yourself as the defendant. The plaintiff would be the person who applied for the restraining order against you. Correctly identify the kind of motion you’re filing, the venue you’re filing it in (that is, which court), and the cause number (and judge, if applicable).

Clerks can’t provide you with legal advice, but they can answer general questions you have about document preparation.

You can easily work up a facsimile of an example caption you find in any decent word processor. Just peck around until you get the effect you want. Make sure everything is double-spaced and that the margins are wide enough for easy reading. Judges aren’t the sticklers for precise measurements that English teachers are. You’re trying to get points across not be given a gold star. Concern yourself more with persuasively conveying your points than with trying to sound like an attorney. Everyday language is fine.

The other thing to remember when filing motions (or any briefs to the court) is to make extra copies for yourself. Have a couple extra copies when you file, in fact, and see that all of the copies are time-stamped or that you get a receipt to confirm that you filed and when you filed.

An alternative to drafting motions from scratch is finding templates of legal forms for your state on the Internet that can be filled in online and printed out. Use these search engine terms and see what they return: your state + legal forms. A site sponsored by your local court system will likely pop up. If there’s a search bar on it, type in motion (or a specific kind of motion). You can also get blank motion forms from the courthouse.

Bear in mind that the worst that can happen if you file a motion is that it’s denied. Filing one in no way disadvantages you or put you in peril of some sinister counteraction. In other words, you have nothing to lose by acting. Here are some motions you may wish to consider:

- MOTION FOR CONTINUANCE or MOTION TO CONTINUE

- MOTION TO DISMISS

- MOTION TO VACATE

- MOTION TO EXPUNGE

Motions to the court for more time mean the same thing everywhere. What motions to dismiss, vacate, or expunge a restraining order may mean, how they’re qualified, when they can be filed, and whether they apply is going to vary from state to state.

At the very least filing a motion (or motions) will impress upon the judge and put the plaintiff on notice that you’re taking your defense seriously. And in all things brought before the court, impressions are paramount. (It’s on the force of impressions, in fact, that many restraining orders are obtained in the first place.)

Admittedly, this post’s title probably overstates the necessity of your filing a motion or motions. It’s just that I can’t resist a pun.

Copyright © 2013 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*Self-represented defendants might also consider familiarizing themselves with various objections that can be raised during trial.

The 148 search engine terms that appear below—at least one to two dozen of which concern false allegations—are ones that brought readers to this blog between the hours of 12 a.m. and 7:21 p.m. yesterday (and don’t include an additional 49 “unknown search terms”).

The 148 search engine terms that appear below—at least one to two dozen of which concern false allegations—are ones that brought readers to this blog between the hours of 12 a.m. and 7:21 p.m. yesterday (and don’t include an additional 49 “unknown search terms”).

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

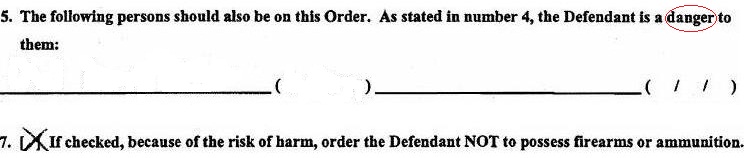

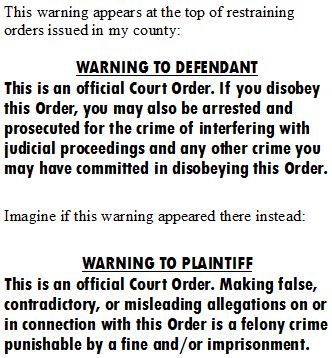

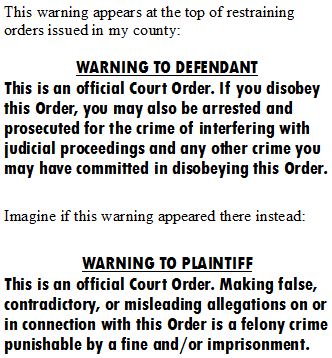

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.