Courts are properly authorized to sanction acts of defamation—publicly lying about someone—but they’re not authorized to prohibit truthful speech or opinion (even if it’s negative), and they’re not authorized to prohibit speech acts before they’ve even been committed. An order of the court that prohibits future speech is called a prior restraint, and it’s unconstitutional (see the First Amendment).

With civil harassment orders, things get knotty. A prior restraint may not be expressed; it may be implicit.

When a “protective order” is in effect, it prohibits speech to someone but not speech about that person, per se, as law professors Aaron Caplan and Eugene Volokh have emphasized. A court, however, may conclude that speech about someone (any speech about that person) is “harassment,” and it may label that speech a violation of the “protective order,” and rule that a defendant be remanded to jail.

When a “protective order” is in effect, it prohibits speech to someone but not speech about that person, per se, as law professors Aaron Caplan and Eugene Volokh have emphasized. A court, however, may conclude that speech about someone (any speech about that person) is “harassment,” and it may label that speech a violation of the “protective order,” and rule that a defendant be remanded to jail.

Several people have reported on this site that they were jailed or had orders of the court extended because of publications online or, in one case, for posting flyers about an accuser’s conduct. Many have reported, too, that the basis of the “protective order” against them was speech about a person (in one recently shared account, a woman complained on a county bulletin board about her neighbors’ shabby treatment of their dog).

So you have instances where people are issued restraining orders for lawfully exercising their First Amendment privilege to free speech, and you have instances where people who’ve been issued restraining orders are sanctioned for lawfully exercising their First Amendment privilege to free speech.

Trial judges aren’t First Amendment authorities and may not have graduated from college, let alone have law degrees. Furthermore, protecting the free speech of people they’ve labeled abusers is hardly an urgent concern of theirs.

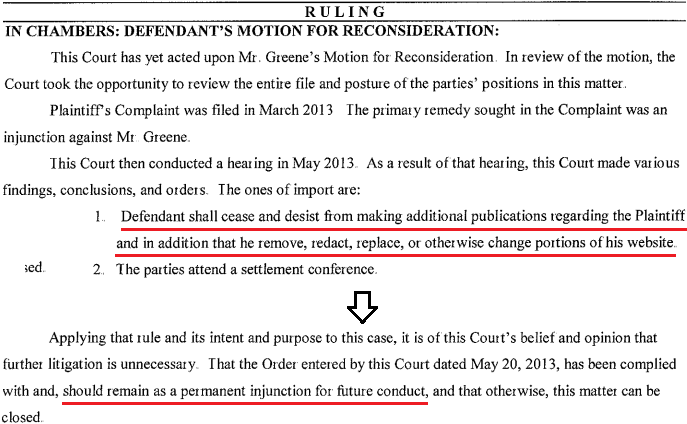

Here’s what a prior restraint looks like:

Orders like this don’t expressly forbid criticism of the government. They forbid criticism of people who exploited a process of government. This, by extension, forbids criticism of the government.

This order was issued against me in 2013 when I was sued for libel and harassment in the Superior Court of Arizona by a married woman who had falsely accused me to the police and several judges years prior. She was someone I scarcely knew who had hung around outside of my house at night (what that might suggest to you is what it should suggest to you). Her original claims to the court (2006) were to obtain an injunction to prohibit me from communicating her conduct to anyone, and her claims to the court in 2013 were to obtain an injunction to prohibit me from communicating her conduct to anyone.

The motive for both prosecutions was the same: cover-up. (Try to imagine what it is to fight false accusations for seven years, daily, while everything around you erodes, and then have some trial judge offhandedly tell you you’re lying and should be gagged. The judge had plainly made up his mind how he would rule before ever setting foot in court. The trial nevertheless dragged out from March to October. Today I avoid using the road where I rented the private mailbox to which the judge’s arbitrary conclusions and fiats were mailed, so nauseous is the association.)

Some of my accuser’s testimony is here, and the contradictoriness of her claims, as well as the motive for them, will be evident from no words other than her own. Does it matter that her misrepresentations are self-evident? No. Does it matter that they ridicule process of law and mock the court? No.

All that matters is that those who’ve been misrepresented are silenced to preserve the image of propriety.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

In an offhand response to a comment yesterday, I remarked that restraining orders weren’t meant to provide people with a sense of security; they were meant to secure people from danger.

In an offhand response to a comment yesterday, I remarked that restraining orders weren’t meant to provide people with a sense of security; they were meant to secure people from danger.