According to a critic of the last post, restraining order abuse is apolitical, and he rejects the writer for not striving “to build a broad, non-ideological [base?] for real restraining order reform.”

According to a critic of the last post, restraining order abuse is apolitical, and he rejects the writer for not striving “to build a broad, non-ideological [base?] for real restraining order reform.”

This is not—or it shouldn’t be—an ideological issue. It’s an issue that affects liberals and conservatives alike, and a problem in liberal and conservative courts. The idea that only liberals and liberal judges abuse restraining orders and that conservative women and conservative courts in conservative jurisdictions never do has zero basis in fact.

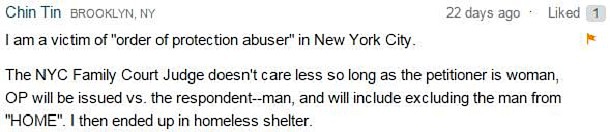

The latter point is true enough: No one is immune to procedural abuse (and that point has been made at least once or twice on this blog).

The “idea” the commenter purports to be responding to is his own. There was no mention in the post of “liberal judges” or “conservative women.” The idea appears to be an imposition on the text provoked by the writer’s pejorative use of the phrase liberal/feminist perspectives, which evidently affronted the commenter.

Note: It’s the hazards of cranky interpretations that most posts on this blog concern. Maybe the critic will detect the irony; maybe he won’t.

His former point, that this “is not…an ideological issue,” is puzzling. Is the issue fraud (i.e., false allegations)? Is it bad law? Lack of accountability? Judicial corruption?

Whatever the perceived “issue” is, the perception itself is superficial. Laws are products of politicking. They’re a response to a social demand. Where did the demand for restraining orders come from, and where the demands that have influenced restraining orders’ legal evolution and application?

To deny women as the source would be silly when the most comprehensive database on restraining order statutes constitutes a website called WomensLaw.org. More pointedly, we might suggest “feminism” as the source, though what that word meant 40 years ago and what it means today are inarguably very different.Can we be more specific yet? Consideration of who specifically advocates for “women’s law” will overwhelmingly recommend the characterization “liberals.” There may be exceptions, sure…but let’s not be coy.

What if we look to critics of restraining orders? Will we find that they’re typically characterized as “conservative”? Whether the characterization is accurate or not…yeah.

It’s not so much that the “issue” divides along party lines; it’s that those who weigh in on either side identify the opposition as “other.” Feminists, for example, may identify Dr. Christina Hoff Sommers (who herself identifies as a feminist philosopher) as “conservative,” and that’s if they’re being polite (here, for instance, is what they call her when they’re not). No one would refer to her as a “liberal”…because we know what liberals are supposed to stand for. (See also, for example, Wendy McElroy, who may be invited on Fox News but not on NPR.)

Clearly, at the nexus of the conflict, there is “party” division.

Denying that the issue is “ideological” or that laws, policies, and practices are influenced by dogma—that’s a different story. It’s starkly wrong.

The critic quoted in this post is right that party identification doesn’t mean a person will be sensitive or callous to procedural abuse, per se, or immunized against it. Purportedly, only about one in five people identifies him- or herself as a feminist (and probably most of the young women of Women Against Feminism broadly identify with liberal values). On the populist level, the “issue” isn’t necessarily a partisan one. Feminists, however, who hold political sway, are predominantly “liberals”; and they do coerce loyalty from others who identify themselves the same way, and rightly or wrongly their values have come to represent their party’s values.

What the previous post highlighted was that liberal ideology (as it manifests in government) ignores reality, and the consequences are reprehensible. Change isn’t motivated by telling people what they’re doing right.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*The previous post was about a real person who was really killed. That policy failed her and that the oversights and indifference of politically motivated policy injure lives on an epic scale—these are also realities.