I this week came across an online monograph with the unwieldy (and very British) title, “Drama Queens, Saviours, Rescuers, Feigners, and Attention-Seekers: Attention-Seeking Personality Disorders, Victim Syndrome, Insecurity, and Centre of Attention Behavior,” which pointedly speaks to a number of behaviors identified by victims of restraining orders who have written in to this blog or alternatively contacted its author concerning the plaintiffs in their cases.

I this week came across an online monograph with the unwieldy (and very British) title, “Drama Queens, Saviours, Rescuers, Feigners, and Attention-Seekers: Attention-Seeking Personality Disorders, Victim Syndrome, Insecurity, and Centre of Attention Behavior,” which pointedly speaks to a number of behaviors identified by victims of restraining orders who have written in to this blog or alternatively contacted its author concerning the plaintiffs in their cases.

What caught my eye, especially, is that this monograph appears on a site titled, BullyOnline.org (now defunct).

The popular perception of restraining orders is that they’re sought by plaintiffs to remedy bullying. The monograph I’ve referenced doesn’t speak to restraining orders, per se, but its revelations about attention-seeking personality disorders are very applicable to abuses of restraining orders and are interesting because they turn the popular perception of restraining order plaintiffs’ motives on its head.

Victims of false restraining orders are urged to consult this monograph for language that may be of assistance both in defining the motives of fraudulent plaintiffs and in cementing an understanding of the psychological exigencies that underlie those motives. Of particular relevance to the subject of this blog are the following personality types sketched by the monograph’s author:

The manipulator: she may exploit family relationships, manipulating others with guilt and distorting perceptions; although she may not harm people physically, she causes everyone to suffer emotional injury. Vulnerable family members are favourite targets. A common attention-seeking ploy is to claim she is being persecuted, victimised, excluded, isolated, or ignored by another family member or group, perhaps insisting she is the target of a campaign of exclusion or harassment.

The mind-poisoner: adept at poisoning people’s minds by manipulating their perceptions of others, especially against the current target.

The drama queen: every incident or opportunity, no matter how insignificant, is exploited, exaggerated, and if necessary distorted to become an event of dramatic proportions. Everything is elevated to crisis proportions. Histrionics may be present where the person feels she is not the centre of attention but should be. Inappropriate flirtatious behaviour may also be present.

The feigner: when called to account and outwitted, the person instinctively uses the denial-counterattack-feigning victimhood strategy to manipulate everyone present, especially bystanders and those in authority. The most effective method of feigning victimhood is to burst into tears, for most people’s instinct is to feel sorry for them, to put their arm round them or offer them a tissue. There’s little more plausible than real tears, although as actresses know, it’s possible to turn these on at will. Feigners are adept at using crocodile tears. From years of practice, attention-seekers often give an Oscar-winning performance in this respect. Feigning victimhood is a favourite tactic of bullies and harassers to evade accountability and sanction. When accused of bullying and harassment, the person immediately turns on the waterworks and claims they are the one being bullied and harassed—even though there’s been no prior mention of being bullied or harassed. It’s the fact that this claim appears after and in response to having been called to account that is revealing. Mature adults do not burst into tears when held accountable for their actions.

The abused: a person claims they are the victim of abuse, sexual abuse, rape, etc. as a way of gaining attention for themselves. Crimes like abuse and rape are difficult to prove at the best of times, and their incidence is so common that it is easy to make a plausible claim as a way of gaining attention.

The victim: she may intentionally create acts of harassment against herself, e.g., send herself hate mail or damage her own possessions in an attempt to incriminate a fellow employee, a family member, neighbour, etc. Scheming, cunning, devious, deceptive, and manipulative, she will identify her “harasser” and produce circumstantial evidence in support of her claim. She will revel in the attention she gains and use her glib charm to plausibly dismiss any suggestion that she herself may be responsible. However, a background check may reveal that this is not the first time she has had this happen to her.

Many respondents to this blog—victims of lovers, spouses or ex-spouses, friends, coworkers, neighbors, or family members—have reported serial behaviors of the aforementioned sorts, and some have discovered that plaintiffs who have sought restraining orders against them are not first-time applicants. One or more of these personality types (or a merger of them) is likely recognizable to most victims of restraining order abuse.

Separate profiles on the “serial bully,” the “attention-seeker,” “narcissistic personality disorder,” and “bullies in the family” appear on the referenced site, and its author estimates that 1/30 people fit its profiles.

Hold this statistic up beside the one propounded by psychologist Martha Stout in her book, The Sociopath Next Door, that an estimated 1/25 people fit the clinical definition of “sociopath”—someone, that is, who’s devoid of moral compunction/empathic identification altogether—and it’s a reasonable proposition that an abundance of allegations made to officers of our courts derive from calculated hokum and that a goodly percentage of restraining orders, far from being sought out of a need for remedial relief, are in fact exploited as instruments of abuse or employed to gratify their plaintiffs’ need to have all eyes focused on them.

Copyright © 2013 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

The 148 search engine terms that appear below—at least one to two dozen of which concern false allegations—are ones that brought readers to this blog between the hours of 12 a.m. and 7:21 p.m. yesterday (and don’t include an additional 49 “unknown search terms”).

The 148 search engine terms that appear below—at least one to two dozen of which concern false allegations—are ones that brought readers to this blog between the hours of 12 a.m. and 7:21 p.m. yesterday (and don’t include an additional 49 “unknown search terms”).

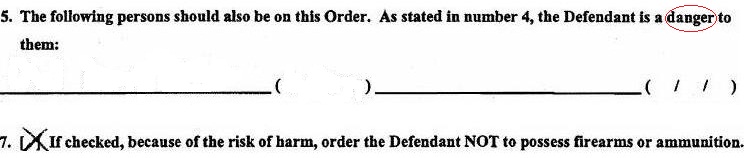

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

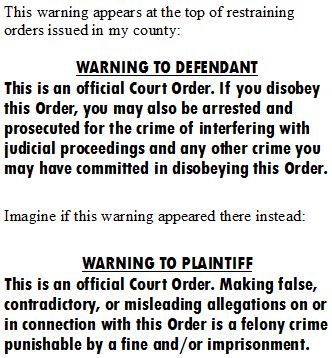

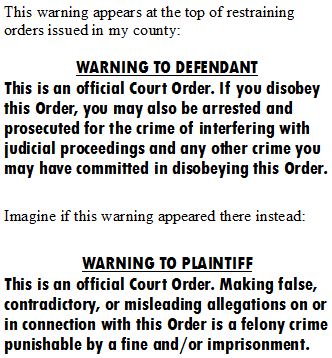

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.