My previous post concerned distortion, specifically by those with narcissistic personality disorder (one of a number of personality disorders that may lead a person to make false allegations, that is, to distort the truth). Restraining order fraud, whether committed by pathological liars or the garden variety, tends to go over smashingly, because judges’ biases (perceptual and otherwise) predispose them to credit and reward fraud.

Below is a list of cognitive distortions (categories of automatic thinking) drawn from Wikipedia interspersed with commentaries. Many if not most of these cognitive distortions are applicable to restraining order decisions and clarify how it is that slanted, hyperbolic, or false allegations made through the medium of the restraining order stick.

Below is a list of cognitive distortions (categories of automatic thinking) drawn from Wikipedia interspersed with commentaries. Many if not most of these cognitive distortions are applicable to restraining order decisions and clarify how it is that slanted, hyperbolic, or false allegations made through the medium of the restraining order stick.

(Cognitive distortion or automatic thinking is pathological thinking associated with neurological disorders.)

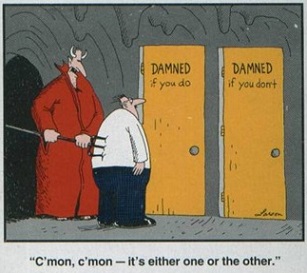

All-or-nothing thinking: seeing things in black or white as opposed to shades of gray; thinking in terms of false dilemmas. Splitting involves using terms like “always,” “every,” or “never” when this is neither true, nor equivalent to the truth.

Restraining order rulings are categorical. They don’t acknowledge gradations of culpability, nor do they address the veracity of individual allegations. Rulings are “yea” or “nay,” with “yea” predominating. That some, most, or all of what a plaintiff alleges is unsubstantiated makes no difference, nor does it matter if some or most of his or her allegations are contradictory or patently false. Restraining order adjudications are zero-sum games.

Overgeneralization: making hasty generalizations from insufficient experiences and evidence.

Restraining order applications are approved upon five or 10 minutes of “deliberation” and in the absence of any controverting testimony from their defendants (who aren’t invited to the party). All rulings, therefore, are arguably hasty and necessarily generic. (They may in fact be mechanical: a groundless restraining order was famously approved against celebrity talk show host David Letterman because its applicant filled out the form correctly.)

Filtering: focusing entirely on negative elements of a situation, to the exclusion of the positive. Also, the brain’s tendency to filter out information which does not conform to already held beliefs.

Judicial attention is only paid to negative representations, and plaintiffs’ representations are likely to be exclusively negative. Judges seek reasons to approve restraining orders sooner than reasons to reject them, and it’s assumed that plaintiffs’ allegations are valid. In fact, it’s commonly mandated that judges presume plaintiffs are telling the truth (despite their possibly having any of several motives to lie).

Disqualifying the positive: discounting positive events.

Mitigating circumstances are typically discounted. Plaintiffs’ perceptions, which may be hysterical, pathologically influenced, or falsely represented, are usually all judges concern themselves with, even after defendants have been given the “opportunity” to contest allegations against them (which opportunity may be afforded no more than 10 to 20 minutes).

Jumping to conclusions: reaching preliminary conclusions (usually negative) from little (if any) evidence.

All conclusions in restraining order cases are jumped-to conclusions. Allegations, which are leveled during brief interviews and against defendants whom judges may never meet, need be no more substantial than “I’m afraid” (a representation that’s easily falsified).

Magnification and minimization: giving proportionally greater weight to a perceived failure, weakness or threat, or lesser weight to a perceived success, strength or opportunity, so the weight differs from that assigned to the event or thing by others.

Judicial inclination is toward approving/upholding restraining orders. In keeping with this imperative, a judge will pick and choose allegations or facts that can be emphatically represented as weighty or “preponderant.” (One recent respondent to this blog shared that a fraudulent restraining order against him was upheld because the judge perceived that he “appear[ed] to be controlling” and that the plaintiff “seem[ed] to have some apprehension toward [him].” While superficial, airy-fairy standards like “appeared” and “seemed” would carry little weight in a criminal procedure, they’re sufficient qualifications to satisfy and sustain a civil restraining order judgment, which is based on judicial discretion.)

Emotional reasoning: presuming that negative feelings expose the true nature of things, and experiencing reality as a reflection of emotionally linked thoughts. Thinking something is true, solely based on a feeling.

The grounds for most restraining orders are alleged emotional states (“I’m afraid,” for example), which judges typically presume to be both honestly represented and valid (that is, reality-based). Consequently, judges may treat defendants cruelly according with their own emotional motives.

Should statements: doing, or expecting others to do, what they morally should or ought to do irrespective of the particular case the person is faced with. This involves conforming strenuously to ethical categorical imperatives which, by definition, “always apply,” or to hypothetical imperatives which apply in that general type of case. Albert Ellis termed this “musturbation.”

All restraining order judgments are essentially generic (and all restraining order defendants are correspondingly treated generically = badly). Particulars are discounted and may well be ignored.

Labeling and mislabeling: a more severe type of overgeneralization; attributing a person’s actions to their character instead of some accidental attribute. Rather than assuming the behavior to be accidental or extrinsic, the person assigns a label to someone or something that implies the character of that person or thing. Mislabeling involves describing an event with language that has a strong connotation of a person’s evaluation of the event.

The basis of a defendant’s “guilt” may be nothing more than a plaintiff’s misperception.

Personalization: attributing personal responsibility, including the resulting praise or blame, for events over which a person has no control.

The restraining order process is entirely geared toward assigning blame to its defendant, regardless of the actual circumstances, of which a judge has only a plaintiff’s representation, a representation that may be false or fantastical. A circumstance a defendant may be blamed for that s/he has no control over, for example, is a plaintiff’s being neurotic, delusional, or deranged.

Blaming: the opposite of personalization; holding other people responsible for the harm they cause, and especially for their intentional or negligent infliction of emotional distress on us.

- Fallacy of change: Relying on social control to obtain cooperative actions from another person.

- Always being right: Prioritizing self-interest over the feelings of another person.

This last category of automatic thinking sums up a judge’s role and m.o. to a T. And, at least in the latter instance (“Always being right”), shouldn’t. If, to the contrary, judges always assumed their first impressions and impulses were wrong, any number of miscarriages of justice might be avoided.

Copyright © 2013 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

The outrage of

The outrage of  Consider whether you don’t think this kind of scenario is more likely to exert a detrimental influence on a child’s development (and whether Jesus wouldn’t have thought so):

Consider whether you don’t think this kind of scenario is more likely to exert a detrimental influence on a child’s development (and whether Jesus wouldn’t have thought so):

Because restraining orders place no limitations on the actions of their plaintiffs (that is, their applicants), stalkers who successfully petition for restraining orders (which are easily had by fraud) may follow their targets around; call, text, or email them; or show up at their homes or places of work with no fear of rejection or repercussion. In fact, any acts to drive them off may be represented to authorities as violations of those stalkers’ restraining orders. It’s very conceivable that a stalker could even assault his or her victim with complete impunity, representing the act of violence as self-defense (and at least one such victim of assault has been brought to this blog).

Because restraining orders place no limitations on the actions of their plaintiffs (that is, their applicants), stalkers who successfully petition for restraining orders (which are easily had by fraud) may follow their targets around; call, text, or email them; or show up at their homes or places of work with no fear of rejection or repercussion. In fact, any acts to drive them off may be represented to authorities as violations of those stalkers’ restraining orders. It’s very conceivable that a stalker could even assault his or her victim with complete impunity, representing the act of violence as self-defense (and at least one such victim of assault has been brought to this blog). Consider: If someone falsely circulates that you’re a sexual harasser, stalker, and/or violent threat—possibly endangering your employment, to say nothing of savaging you psychologically—you can report that person to the police, seek a restraining order against that person for harassment, and/or sue that person for defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress. If, however, that person first obtains a restraining order against you based on the same false allegations—which is simply a matter of filling out a form and lying to a judge for five or 10 minutes—s/he can then circulate those allegations, which have been officially recognized as legitimate on an order of the court, with impunity. Your credibility, both among colleagues, perhaps, as well as with authorities and the courts, is instantly shot. You may, besides, be subject to police interference based on further false allegations, or even jailed (arrest for violation of a restraining order doesn’t require that the arresting officer actually witness or have incontrovertible proof of anything). And if you are arrested, your credibility is so hopelessly compromised that a false accuser can successfully continue a campaign of harassment indefinitely. Not only that, s/he can expect to do so with the solicitous support and approval of all those who recognize him or her as a “victim” (which may be practically everyone).

Consider: If someone falsely circulates that you’re a sexual harasser, stalker, and/or violent threat—possibly endangering your employment, to say nothing of savaging you psychologically—you can report that person to the police, seek a restraining order against that person for harassment, and/or sue that person for defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress. If, however, that person first obtains a restraining order against you based on the same false allegations—which is simply a matter of filling out a form and lying to a judge for five or 10 minutes—s/he can then circulate those allegations, which have been officially recognized as legitimate on an order of the court, with impunity. Your credibility, both among colleagues, perhaps, as well as with authorities and the courts, is instantly shot. You may, besides, be subject to police interference based on further false allegations, or even jailed (arrest for violation of a restraining order doesn’t require that the arresting officer actually witness or have incontrovertible proof of anything). And if you are arrested, your credibility is so hopelessly compromised that a false accuser can successfully continue a campaign of harassment indefinitely. Not only that, s/he can expect to do so with the solicitous support and approval of all those who recognize him or her as a “victim” (which may be practically everyone). Restraining orders are unparalleled tools for discrediting, intimidating, and silencing those they’ve been petitioned against. It’s presumed that those people (their defendants) are menaces of one sort or another. Why else would they be accused?

Restraining orders are unparalleled tools for discrediting, intimidating, and silencing those they’ve been petitioned against. It’s presumed that those people (their defendants) are menaces of one sort or another. Why else would they be accused? Memorable stories of restraining orders’ being used to conceal (or indulge) indiscretions or infidelities that have been shared with me since I began this blog over two years ago include a woman’s being accused of domestic violence by a former boyfriend she briefly renewed a (Platonic) friendship with who had a viciously jealous wife who put him up to it; a man’s being charged with domestic violence after catching his wife texting her lover and wrestling with her for possession of the phone for an hour (he was forced to abandon his house so his rival could move in); and a young , female attorney’s being seduced by an older, married colleague who never told her he was married and subsequently petitioned an emergency restraining order against her, both to shut her up and to minimize her opportunity to prepare a defense. I’ve even been apprised of people’s (women’s) having restraining orders petitioned against them by spouses (women) who resented being informed of their mates’ sleeping around.

Memorable stories of restraining orders’ being used to conceal (or indulge) indiscretions or infidelities that have been shared with me since I began this blog over two years ago include a woman’s being accused of domestic violence by a former boyfriend she briefly renewed a (Platonic) friendship with who had a viciously jealous wife who put him up to it; a man’s being charged with domestic violence after catching his wife texting her lover and wrestling with her for possession of the phone for an hour (he was forced to abandon his house so his rival could move in); and a young , female attorney’s being seduced by an older, married colleague who never told her he was married and subsequently petitioned an emergency restraining order against her, both to shut her up and to minimize her opportunity to prepare a defense. I’ve even been apprised of people’s (women’s) having restraining orders petitioned against them by spouses (women) who resented being informed of their mates’ sleeping around. What this blog and

What this blog and

That’s why I’m particularly impressed when I encounter writers whose literary protests are not only controlled but very lucid and balanced. One such writer maintains a blog titled

That’s why I’m particularly impressed when I encounter writers whose literary protests are not only controlled but very lucid and balanced. One such writer maintains a blog titled  Casual charlatanism, though, is hardly an accomplishment for people without consciences to answer to. And rubes and tools are ten cents a dozen.

Casual charlatanism, though, is hardly an accomplishment for people without consciences to answer to. And rubes and tools are ten cents a dozen.

A principle of law that everyone ensnarled in any sort of legal shenanigan should be aware of is stare decisis. This Latin phrase means “to abide by, or adhere to, decided things” (Black’s Law Dictionary). Law proceeds and “evolves” in accordance with stare decisis.

A principle of law that everyone ensnarled in any sort of legal shenanigan should be aware of is stare decisis. This Latin phrase means “to abide by, or adhere to, decided things” (Black’s Law Dictionary). Law proceeds and “evolves” in accordance with stare decisis.

This means defendants can be denied access to the family pet(s), besides.

This means defendants can be denied access to the family pet(s), besides. I had an exceptional encounter with an exceptional woman this week who was raped as a child (by a child) and later violently raped as a young adult, and whose assailants were never held accountable for their actions. It’s her firm conviction—and one supported by her own experiences and those of women she’s counseled—that allegations of rape and violence in criminal court can too easily be dismissed when, for example, a woman has voluntarily entered a man’s living quarters and an expectation of consent to intercourse has been aroused.

I had an exceptional encounter with an exceptional woman this week who was raped as a child (by a child) and later violently raped as a young adult, and whose assailants were never held accountable for their actions. It’s her firm conviction—and one supported by her own experiences and those of women she’s counseled—that allegations of rape and violence in criminal court can too easily be dismissed when, for example, a woman has voluntarily entered a man’s living quarters and an expectation of consent to intercourse has been aroused. Lapses by the courts have piqued the outrage of victims of both genders against the opposite gender, because most victims of rape are female, and most victims of false allegations are male.

Lapses by the courts have piqued the outrage of victims of both genders against the opposite gender, because most victims of rape are female, and most victims of false allegations are male. As many people who’ve responded to this blog have been, this woman was used and abused then publicly condemned and humiliated to compound the torment. She’s shelled out thousands in legal fees, lost a job, is in therapy to try to maintain her sanity, and is due back in court next week. And she has three kids who depend on her.

As many people who’ve responded to this blog have been, this woman was used and abused then publicly condemned and humiliated to compound the torment. She’s shelled out thousands in legal fees, lost a job, is in therapy to try to maintain her sanity, and is due back in court next week. And she has three kids who depend on her.

The

The  Not many years ago, philosopher Harry Frankfurt published a treatise that I was amused to discover called

Not many years ago, philosopher Harry Frankfurt published a treatise that I was amused to discover called  The logical extension of there being no consequences for lying is there being no consequences for lying back. Bigger and better.

The logical extension of there being no consequences for lying is there being no consequences for lying back. Bigger and better. The sad and disgusting fact is that success in the courts, particularly in the drive-thru arena of restraining order prosecution, is largely about impressions. Ask yourself who’s likelier to make the more impressive showing: the liar who’s free to let his or her imagination run wickedly rampant or the honest person who’s constrained by ethics to be faithful to the facts?

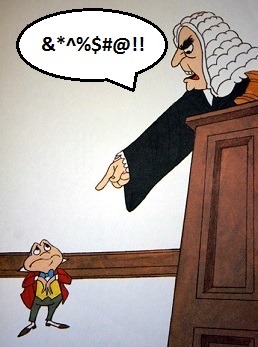

The sad and disgusting fact is that success in the courts, particularly in the drive-thru arena of restraining order prosecution, is largely about impressions. Ask yourself who’s likelier to make the more impressive showing: the liar who’s free to let his or her imagination run wickedly rampant or the honest person who’s constrained by ethics to be faithful to the facts? Judicial misbehavior is often complained of by defendants who’ve been abused by the restraining order process. Cited instances include gross dereliction, judge-attorney cronyism, gender bias, open contempt, and warrantless verbal cruelty. Avenues for seeking the censure of a judge who has engaged in negligent or vicious misconduct vary from state to state. In my own state of Arizona, complaints may be filed with the Commission on Judicial Conduct. Similar boards, panels, and tribunals exist in most other states.

Judicial misbehavior is often complained of by defendants who’ve been abused by the restraining order process. Cited instances include gross dereliction, judge-attorney cronyism, gender bias, open contempt, and warrantless verbal cruelty. Avenues for seeking the censure of a judge who has engaged in negligent or vicious misconduct vary from state to state. In my own state of Arizona, complaints may be filed with the Commission on Judicial Conduct. Similar boards, panels, and tribunals exist in most other states.

A person who obtains a fraudulent restraining order or otherwise abuses the system to bring you down with false allegations does so because you didn’t bend to his or her will like you were supposed to do.

A person who obtains a fraudulent restraining order or otherwise abuses the system to bring you down with false allegations does so because you didn’t bend to his or her will like you were supposed to do.

I’ve recently tried to debunk some of the

I’ve recently tried to debunk some of the

What most people don’t get about restraining orders is how much they have in common with Mad Libs. You know, that party game where you fill in random nouns, verbs, and modifiers to concoct a zany story? What petitioners fill in the blanks on restraining order applications with is typically more deliberate but may be no less farcical.

What most people don’t get about restraining orders is how much they have in common with Mad Libs. You know, that party game where you fill in random nouns, verbs, and modifiers to concoct a zany story? What petitioners fill in the blanks on restraining order applications with is typically more deliberate but may be no less farcical.

Lawyers and judges I’ve talked to readily own their disenchantment with restraining order policy and don’t hesitate to acknowledge its malodor. It’s very rare, though, to find a quotation in print from an officer of the court that says as much. Job security is as important to them as it is to the next guy, and restraining orders are a political hot potato, because the feminist lobby is a powerful one and one that’s not distinguished for its temperateness or receptiveness to compromise or criticism.

Lawyers and judges I’ve talked to readily own their disenchantment with restraining order policy and don’t hesitate to acknowledge its malodor. It’s very rare, though, to find a quotation in print from an officer of the court that says as much. Job security is as important to them as it is to the next guy, and restraining orders are a political hot potato, because the feminist lobby is a powerful one and one that’s not distinguished for its temperateness or receptiveness to compromise or criticism.