The subject of this excursion is “domestic violence,” which phrase is placed in quotation marks because it’s a suspect term that’s become so broadly inclusive as to mean virtually anything a user wants it to.

This is how domestic violence is defined by the American Psychiatric Association—and by many states’ statutes, as well:

Domestic violence is control by one partner over another in a dating, marital, or live-in relationship. The means of control include physical, sexual, emotional, and economic abuse, threats, and isolation.

Emphatically noteworthy at the outset of this discussion is that false allegations of domestic violence have the same motive identified by the APA that domestic violence has: “control”; have the same consequences: “psychological and economic entrapment [and] physical isolation”; use the same methods to abuse: “fear of social judgment, threats, and intimidation”; have the same mental health effects on victims: “depression, anxiety, panic attacks, substance abuse, and post-traumatic stress disorder”; and can also “trigger suicide attempts [and] homelessness.”

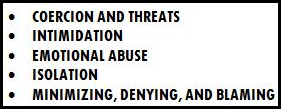

A domestic violence factsheet published by the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence features a “Power and Control” pie chart. These segments of it are ALSO among the motives and effects of false allegations.

Accordingly, then, making false allegations of domestic violence is domestic violence.

When I was a kid, domestic violence meant something very distinct. It meant serial violence, specifically the habitual bullying or wanton battery by a man of his wife. The phrase represented a chronic behavior, one that gave rise to terms like battered-wife syndrome and to domestic violence and restraining order statutes.

These days, however, domestic violence, which is the predominant grounds for the issuance of civil protection orders, can be a single act, an act whose qualification as “violence” may be highly dubious, and an act not only of a man but of a woman (that can be alleged on a restraining order application merely by ticking a box).

As journalist Cathy Young observed more than 15 years ago, the War on Domestic Violence, which was “[b]orn partly in response to an earlier tendency to treat wife-beating as nothing more than a marital sport,” has caused the suspension of rational standards of discernment and introduced martial law into our courtrooms. “[T]his campaign treats all relationship conflict as a crime. The zero-tolerance mentality of current domestic violence policy means that no offense is too trivial, not only for arrest but for prosecution.” Reduced standards of judicial discrimination inspired by this absolutist mentality further mean that even falsely alleged minor offenses are both credited and treated as urgent and damnable.

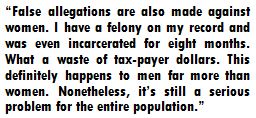

Consider this recent account posted to the e-petition Stop False Allegations of Domestic Violence:

My boyfriend accused me of DV after an argument about separating and my 18-month-old…. The officer arrested me in front of my daughter, and when I asked why, he said he had a scratch on his arm.

A scratch.

The woman goes on to report that she spent two days in jail, had to post a $5,000 bond to get out, and that she was subsequently “displaced” from her former life.

Here’s another:

My ex-husband told the police that I pushed him, even though a witness had called the police on him for pushing me. He was completely drunk…but I got arrested instead. Right in front of my stunned family.

And another:

I was accused of domestic violence because I pinched my ex-husband when he pinned me and my son between two trucks. He ruined my life.

A scratch, a push, a pinch—which may not even have been real but whose allegation had real enough consequences.

A scratch, a push, a pinch—which may not even have been real but whose allegation had real enough consequences.

I’ve also heard from and written about a man who caught his wife texting her lover and tried to take her phone. The two rowed for an hour, wrestling for it. The upshot was that the man was arrested and tried for domestic violence and ended up having to forfeit the home they shared to his wife, into which she had already moved her boyfriend.

(This week, I was contacted by a man trying to vacate an old restraining order whose story is identical: “[T]he only incident was in 2008 when I caught her cheating and tried to grab her phone.”)

False allegations to shift blame for misconduct are common, as are stories like these—stories of lives turned upside down by acts of “violence” that are daily tolerated by little kids—and they’re the motive of my politically incorrect two cents.

I read a feminist bulletin about domestic violence not long ago that featured for its graphic a woman who had very conspicuously been punched in the eye. Her injury was certainly more serious than a scratch or a pinch, but it, too, may have represented a single occurrence and was an injury that would heal within a month or two at the outside.

The gravity with which a single act of assault like this is regarded by the justice system can’t be overstated. The perpetrator is liable to have the book thrown at him.

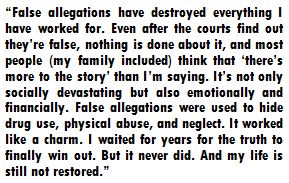

By contrast, false allegations of domestic violence—or any number of other disreputable offenses—aren’t regarded by the courts or the public with any gravity at all, and their injuries don’t go away.

I work outside with my hands most days—which I wouldn’t be doing if I hadn’t had my own aspirations curtailed by the courts years ago (not based on allegations of domestic violence but on ones sufficiently crippling). I bang, stab, and gash myself routinely. From stress, besides, I’m prone to the occasional ruptured capillary in one of my eyes. I wouldn’t tolerate someone’s hurting a woman—or anyone else—in my presence, but at the same time, if I were offered the chance to recover my name, my peace of mind, and the years I’ve lost by taking a punch in the eye, I’d take the punch. In fact, I’d take many more than one.

I think other targets of false allegations who’ve had their lives wrung dry by them would say the same.

In my 20s, I was run down in the road when I left my vehicle to go to the help of a maimed animal. A 35-year-old guy, driving on a lit street under a full moon, smashed into me hard enough to lift me out of my shoes. The consequences of my injuries are ones I still live with, but a few surgeries and a year later, I was walking without a noticeable limp. I haven’t given the driver another thought since and couldn’t tell you his last name today. I think it started with an M.

Not only do I dispute the idea that physical injuries are worse than injuries done by fraudulent abuse of legal process; I don’t believe most physical injuries even compare.

And I think victims of domestic terrorism, whose torments are ridiculed by false accusers, would acknowledge that the lasting damage of that terrorism is psychic, which further corroborates my point.

Such violation promotes insecurity, distrust, and a state of constant anxiety—exactly as false allegations to authorities and the courts do, which may besides strip from a victim everything s/he has, everything s/he is, and possibly everything that s/he hoped to have and be.

There are no support groups for victims like this—nor shelters, nor relief, nor sympathy. Victims of lies aren’t even recognized as victims.

I’ve written recently about the abuse of restraining orders by fraudulent litigants to punish. What needs observation is that the laws themselves, that is, restraining order and domestic violence statutes, are corrupted by the same motive: to punish. Their motive is not simply to protect (a fact that’s borne out by the prosecution of alleged pinchers).

I’ve written recently about the abuse of restraining orders by fraudulent litigants to punish. What needs observation is that the laws themselves, that is, restraining order and domestic violence statutes, are corrupted by the same motive: to punish. Their motive is not simply to protect (a fact that’s borne out by the prosecution of alleged pinchers).

Reforms meant to apply perspective to these statutes and reduce miscarriages of justice from their exploitation have been proposed; they’ve just been vehemently resisted by the feminist establishment.

Laws that were conceived decades ago to redress a serious societal problem have not only been let out at the seams but are easily contorted into tools of domestic violence. This hasn’t been accomplished by fraudulent manipulators of legal process, who merely take advantage of a readily available weapon; it’s rather the product of a dogmatic will to punish exerted by advocates who wouldn’t concede that even real scratches, pushes, or pinches are hardly just grounds for having people forcibly detained, tried, and exiled.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

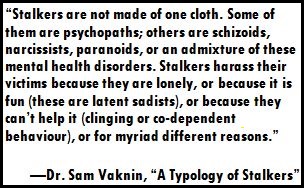

What a broader yet nuanced definition of stalking like Dr. Palmatier’s reveals is that what makes someone a stalker isn’t how his or her target perceives him or her; it’s how s/he perceives his or her target: as an object (what stalking literally means is the stealthy pursuit of prey—that is, food).

What a broader yet nuanced definition of stalking like Dr. Palmatier’s reveals is that what makes someone a stalker isn’t how his or her target perceives him or her; it’s how s/he perceives his or her target: as an object (what stalking literally means is the stealthy pursuit of prey—that is, food). Placed in proper perspective, then, not all acts of stalkers are rejected or alarming, because their targets don’t perceive their motives as deviant or predatory. The overtures of stalkers, interpreted as normal courtship behaviors, may be invited or even welcomed by the unsuspecting.

Placed in proper perspective, then, not all acts of stalkers are rejected or alarming, because their targets don’t perceive their motives as deviant or predatory. The overtures of stalkers, interpreted as normal courtship behaviors, may be invited or even welcomed by the unsuspecting. courts by disordered personalities as stalkers ignite in them the need to clear their names, on which their livelihoods may depend (never mind their sanity); and their determination, which for obvious reasons may be obsessive, seemingly corroborates stalkers’ false allegations of stalking.

courts by disordered personalities as stalkers ignite in them the need to clear their names, on which their livelihoods may depend (never mind their sanity); and their determination, which for obvious reasons may be obsessive, seemingly corroborates stalkers’ false allegations of stalking.

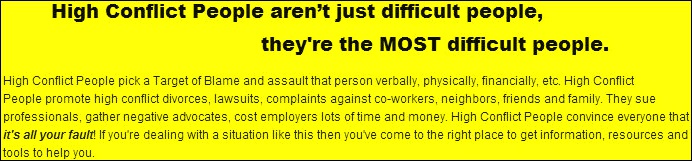

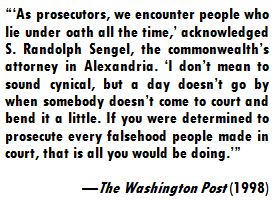

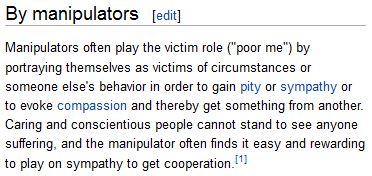

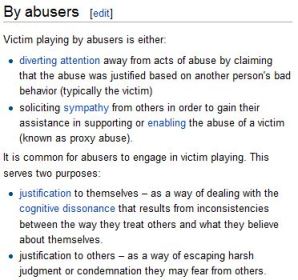

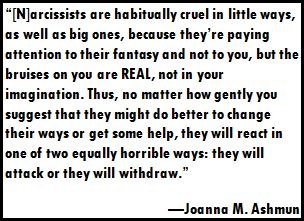

Contemplating these statements should also make clear the all-but-impossible task that counteracting the fraudulent allegations of high-conflict people can pose, both because disordered personalities lie without compunction and because they’re intensely invested in domination, blaming, and punishment.

Contemplating these statements should also make clear the all-but-impossible task that counteracting the fraudulent allegations of high-conflict people can pose, both because disordered personalities lie without compunction and because they’re intensely invested in domination, blaming, and punishment. I’ve read Freud, Lacan, and some other abstruse psychology texts, because I was trained as a literary analyst, and psychological theories are sometimes used by textual critics as interpretive prisms. None of these equipped me, though, to understand the kind of person who would wantonly lie to police officers and judges, enlist others in smear campaigns, and/or otherwise engage in dedicatedly vicious misconduct.

I’ve read Freud, Lacan, and some other abstruse psychology texts, because I was trained as a literary analyst, and psychological theories are sometimes used by textual critics as interpretive prisms. None of these equipped me, though, to understand the kind of person who would wantonly lie to police officers and judges, enlist others in smear campaigns, and/or otherwise engage in dedicatedly vicious misconduct.

If you’ve been attacked serially by someone you trusted who’s abused legal process to hurt you, spread false rumors about you, made false allegations against you, and otherwise manipulated others to join in bullying you (possibly over a period spanning years and despite your reasonable attempts to settle the situation), your persecutor is an example of the high-conflict person to whom the epigraph refers, and understanding his or her motives may be of value to your self-protection.

If you’ve been attacked serially by someone you trusted who’s abused legal process to hurt you, spread false rumors about you, made false allegations against you, and otherwise manipulated others to join in bullying you (possibly over a period spanning years and despite your reasonable attempts to settle the situation), your persecutor is an example of the high-conflict person to whom the epigraph refers, and understanding his or her motives may be of value to your self-protection. So enculturated has the belief that women are helpless victims become that no one recognizes that feminist political might is unrivaled—unrivaled—and it’s in the interest of preserving that political might and enhancing it that the belief that women are helpless victims is vigorously promulgated by the feminist establishment that should be promoting the idea that women aren’t helpless.

So enculturated has the belief that women are helpless victims become that no one recognizes that feminist political might is unrivaled—unrivaled—and it’s in the interest of preserving that political might and enhancing it that the belief that women are helpless victims is vigorously promulgated by the feminist establishment that should be promoting the idea that women aren’t helpless.

Learning the ins and outs of restraining order litigation has for this writer been an ongoing educational process bordering on a descent into hell that he’s only submitted to with a great deal of teeth-gnashing. In my state (Arizona), it’s possible for a plaintiff who’s petitioned for a restraining order in civil court to return to the same court and file a

Learning the ins and outs of restraining order litigation has for this writer been an ongoing educational process bordering on a descent into hell that he’s only submitted to with a great deal of teeth-gnashing. In my state (Arizona), it’s possible for a plaintiff who’s petitioned for a restraining order in civil court to return to the same court and file a  Noteworthy finally is Ms. Malloy’s acknowledgment that false allegations of violence, which are devastating in the emotional oppression, humiliation, and social and professional havoc they wreak on the falsely accused, are used strategically to gain leverage in divorce proceedings.

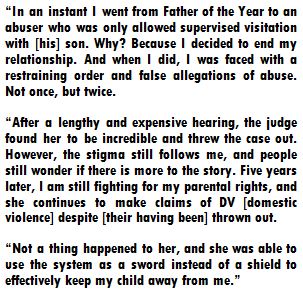

Noteworthy finally is Ms. Malloy’s acknowledgment that false allegations of violence, which are devastating in the emotional oppression, humiliation, and social and professional havoc they wreak on the falsely accused, are used strategically to gain leverage in divorce proceedings.

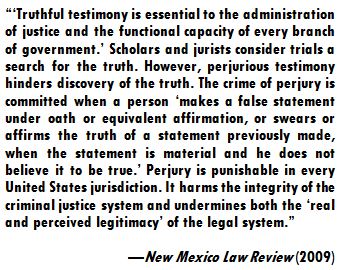

Disturbing, also, are that the phrase miscarriages of justice is typically only applied to wrongful criminal convictions and that false allegations are discounted as contributing significantly to the number of miscarriages of justice, when in fact they’re responsible for the majority of them. Fraudulent claims are certainly unexceptional in civil proceedings, and the successes of fraudulent claims in civil court are just as much miscarriages of justice as failures of the system that result in false criminal convictions are.

Disturbing, also, are that the phrase miscarriages of justice is typically only applied to wrongful criminal convictions and that false allegations are discounted as contributing significantly to the number of miscarriages of justice, when in fact they’re responsible for the majority of them. Fraudulent claims are certainly unexceptional in civil proceedings, and the successes of fraudulent claims in civil court are just as much miscarriages of justice as failures of the system that result in false criminal convictions are. The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin I’ve quoted goes on at some length to detail the difficulties and complexities that unraveling false claims entails for agents of the FBI. Appreciate then how absurd is the state’s faith that a single judge—or a couple of them—can ascertain the truth of civil restraining order allegations by auditing claims in a hearing or hearings arrived at with no prior information, that last mere minutes, and that are furthermore biased by the preconception that the accused is guilty.

The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin I’ve quoted goes on at some length to detail the difficulties and complexities that unraveling false claims entails for agents of the FBI. Appreciate then how absurd is the state’s faith that a single judge—or a couple of them—can ascertain the truth of civil restraining order allegations by auditing claims in a hearing or hearings arrived at with no prior information, that last mere minutes, and that are furthermore biased by the preconception that the accused is guilty. The first of these important facts is that the nanny state issues restraining orders carelessly, tactlessly, and callously. Their recipients are completely bewildered, and no one actually explains to them what a restraining order signifies, what its specific prohibitions are, or anything else. If a cop is involved, s/he may impress upon a restraining order recipient that the court’s order should be “taken very seriously.” (“What should be taken very seriously?” “The court’s order!”) That’s it. Not one person involved even inquires, for example, whether the restraining order recipient is sighted (as opposed to stone blind), mentally competent, or knows how to read. Restraining orders are casually dispensed (millions of them, each year) and then, unless they’re violated intentionally or accidentally (and motive doesn’t matter; the cops swoop in, regardless), they’re dispensed with: “NEXT!” “NEXT!” “NEXT!” It’s a revolving-door process that’s administered by conveyor belt but enforced with rigorous menace. That’s the first important fact.

The first of these important facts is that the nanny state issues restraining orders carelessly, tactlessly, and callously. Their recipients are completely bewildered, and no one actually explains to them what a restraining order signifies, what its specific prohibitions are, or anything else. If a cop is involved, s/he may impress upon a restraining order recipient that the court’s order should be “taken very seriously.” (“What should be taken very seriously?” “The court’s order!”) That’s it. Not one person involved even inquires, for example, whether the restraining order recipient is sighted (as opposed to stone blind), mentally competent, or knows how to read. Restraining orders are casually dispensed (millions of them, each year) and then, unless they’re violated intentionally or accidentally (and motive doesn’t matter; the cops swoop in, regardless), they’re dispensed with: “NEXT!” “NEXT!” “NEXT!” It’s a revolving-door process that’s administered by conveyor belt but enforced with rigorous menace. That’s the first important fact.

The very real if inconvenient truth remains that victims of false allegations made to authorities and the courts present with the same symptoms highlighted in the epigraph: “fear, anxiety, nervousness, self-blame, anger, shame, and difficulty sleeping”—among a host of others. And that’s just the ones who aren’t robbed of everything that made their lives meaningful, including home, property, and family. In the latter case, post-traumatic stress disorder may be the least of their torments. They may be left homeless, penniless, childless, and emotionally scarred.

The very real if inconvenient truth remains that victims of false allegations made to authorities and the courts present with the same symptoms highlighted in the epigraph: “fear, anxiety, nervousness, self-blame, anger, shame, and difficulty sleeping”—among a host of others. And that’s just the ones who aren’t robbed of everything that made their lives meaningful, including home, property, and family. In the latter case, post-traumatic stress disorder may be the least of their torments. They may be left homeless, penniless, childless, and emotionally scarred.

Right, the faker (opportunist, easy-outer, buck-passer, hysteric, bully, vengeance- or attention-seeker, crank, sociopath, neurotic, disordered personality, etc.).

Right, the faker (opportunist, easy-outer, buck-passer, hysteric, bully, vengeance- or attention-seeker, crank, sociopath, neurotic, disordered personality, etc.). What I discovered was that group-bullying certainly is a recognized social phenomenon among kids, and it’s one that’s given rise to the coinage cyberbullying and been credited with inspiring teen suicide. The clinical term for this conduct is

What I discovered was that group-bullying certainly is a recognized social phenomenon among kids, and it’s one that’s given rise to the coinage cyberbullying and been credited with inspiring teen suicide. The clinical term for this conduct is

“I am a landlord, and on Jan. 22, I had the sheriff issue a tenant/roommate a ‘notice to quit’ by the end of the month. The tenant, in retaliation the very next day, requested from the courts that I be slapped with a restraining order and be ordered to stay 100 yards away from her. I guess, lucky for me, the judge did not grant her the 100 yards, which would have gotten me out of my own house.

“I am a landlord, and on Jan. 22, I had the sheriff issue a tenant/roommate a ‘notice to quit’ by the end of the month. The tenant, in retaliation the very next day, requested from the courts that I be slapped with a restraining order and be ordered to stay 100 yards away from her. I guess, lucky for me, the judge did not grant her the 100 yards, which would have gotten me out of my own house. “Narcissistic people do fall in love, but they usually fall in love with being in love—and not with you. They crave the excitement of love, but are quickly disappointed when it becomes a relationship—and not just a trip into fantasy.”

“Narcissistic people do fall in love, but they usually fall in love with being in love—and not with you. They crave the excitement of love, but are quickly disappointed when it becomes a relationship—and not just a trip into fantasy.” Something I neglected to explicitly observe in the recent post referenced in the introduction that may merit observation is that all narcissists are stalkers (whether latent or active) insofar as the objects of narcissists’ romance fantasies are always merely objects to them (psycho-emotional gas pumps); they’re never subjects. What distinguishes the narcissistic stalker is that s/he’s seldom recognized for what s/he is, so s/he’s seldom rejected for what s/he is. Realize that the difference between normal pursuit behavior and aberrant pursuit behavior may be nothing more than how the pursued feels about it. Narcissists choose targets they perceive as vulnerable (empathic, tolerant, and pliable).

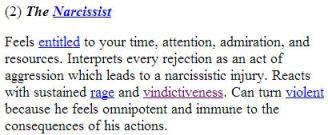

Something I neglected to explicitly observe in the recent post referenced in the introduction that may merit observation is that all narcissists are stalkers (whether latent or active) insofar as the objects of narcissists’ romance fantasies are always merely objects to them (psycho-emotional gas pumps); they’re never subjects. What distinguishes the narcissistic stalker is that s/he’s seldom recognized for what s/he is, so s/he’s seldom rejected for what s/he is. Realize that the difference between normal pursuit behavior and aberrant pursuit behavior may be nothing more than how the pursued feels about it. Narcissists choose targets they perceive as vulnerable (empathic, tolerant, and pliable). Once the other fails to satisfy the psycho-emotional needs of the narcissist, corrupts his or her fantasy, or by intimacy threatens the autonomy of the narcissist or the reality s/he’s primarily invested in, the narcissist’s pathology is such that s/he can instantly blame the other (whom the narcissist targeted in the first place) for his or her perceived “betrayal.”

Once the other fails to satisfy the psycho-emotional needs of the narcissist, corrupts his or her fantasy, or by intimacy threatens the autonomy of the narcissist or the reality s/he’s primarily invested in, the narcissist’s pathology is such that s/he can instantly blame the other (whom the narcissist targeted in the first place) for his or her perceived “betrayal.”

In “

In “

Rape and domestic violence happen. There’s no question about it. There’s likewise no question that their effects may be damaging beyond either qualification or quantification.

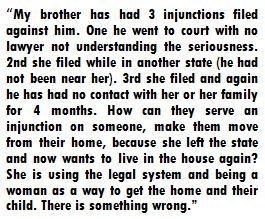

Rape and domestic violence happen. There’s no question about it. There’s likewise no question that their effects may be damaging beyond either qualification or quantification. A significant number, if not the majority, of respondents to this blog who report being the victims of false allegations on restraining orders—particularly the ones who detail their stories at length—are women. This doesn’t mean that women, who represent less than 20% of restraining order defendants, are more commonly the victims of false allegations. It’s indicative, rather, of women’s disposition to socially connect and express their pain, indignity, and outrage. (Women, furthermore, aren’t perceived as dangerous and deviant, so they feel less insecure about publicly declaiming their innocence; they have the greater expectation of being believed and receiving sympathy.)

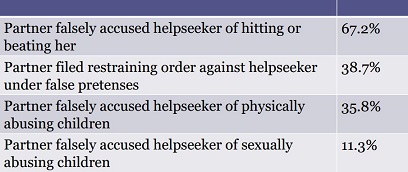

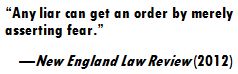

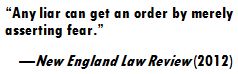

A significant number, if not the majority, of respondents to this blog who report being the victims of false allegations on restraining orders—particularly the ones who detail their stories at length—are women. This doesn’t mean that women, who represent less than 20% of restraining order defendants, are more commonly the victims of false allegations. It’s indicative, rather, of women’s disposition to socially connect and express their pain, indignity, and outrage. (Women, furthermore, aren’t perceived as dangerous and deviant, so they feel less insecure about publicly declaiming their innocence; they have the greater expectation of being believed and receiving sympathy.) If you imagine there are hard-and-fast rules that apply to what a judge can issue a restraining order for, think again. Grounds for establishing “harassment” or vague emotional allegations like fear need only be their plaintiffs’ assertion. Plaintiffs don’t even

If you imagine there are hard-and-fast rules that apply to what a judge can issue a restraining order for, think again. Grounds for establishing “harassment” or vague emotional allegations like fear need only be their plaintiffs’ assertion. Plaintiffs don’t even