Since I began culling various “motions to dismiss” that allow plaintiffs in different states to vacate (cancel) restraining orders that they’ve applied for, the motion forms have attracted between 10 and 40 visitors a day.

Since I began culling various “motions to dismiss” that allow plaintiffs in different states to vacate (cancel) restraining orders that they’ve applied for, the motion forms have attracted between 10 and 40 visitors a day.

Dropping a restraining order is a straightforward process. The restraining order applicant returns to the courthouse and files an affidavit (sworn statement) explaining his or her reasons for wishing to have the order dismissed, which may require an additional hearing before a judge. On its surface, the procedure is easy-peasy (albeit inconvenient and possibly nerve-wracking).

If the restraining order was petitioned in anger or the petitioner simply acted “without thinking,” withdrawing it is furthermore an ethical no-brainer, and it may be sufficient for the petitioner to tell the court that s/he no longer considers the order necessary.

If the restraining order was petitioned in anger or the petitioner simply acted “without thinking,” withdrawing it is furthermore an ethical no-brainer, and it may be sufficient for the petitioner to tell the court that s/he no longer considers the order necessary.

Potential complications, nevertheless, are manifold. Applications for restraining orders, even ones falsely or impetuously obtained, may have been motivated or encouraged by others, and withdrawing them must be done against their urgent disapproval. These others are often family members or girlfriends who get swept up in the drama, which can excite a frenzy approaching bloodlust.

Some minor domestic fracas or even just an expression of discontentment may become for them a point to concentrate their collective resentments toward men or toward the particular man who’s been accused (and the gender reverse isn’t inconceivable).

“Don’t do it!” plaintiffs may be told. “You’ll get in trouble for lying and go to jail!” Plaintiffs with children may moreover be terrorized with doomful predictions of harassment by child protective services: “They’ll take your kids!”

Concerns about being prosecuted by the state for falsely alleging fear are unwarranted. Concerns about the state continuing to sniff around a plaintiff’s household, however, aren’t baseless. It happens.

Concerns about being prosecuted by the state for falsely alleging fear are unwarranted. Concerns about the state continuing to sniff around a plaintiff’s household, however, aren’t baseless. It happens.

Here, for example, is how judges are prompted to proceed in Texas:

When an applicant seeks to dismiss the protective order or wants to withdraw an application for a protective order, the court should have the request investigated before ruling.

The nanny state’s presumption that plaintiffs’ fears are real and urgent makes obtaining restraining orders, even by arrant fraud, child’s play. But the same presumption means the state may be reluctant to concede that it was duped. It’s been primed, in other words, to look for mischief, and it doesn’t always passively back down.

Returning to The Texas Family Violence Benchbook (a benchbook is an instruction manual for judges):

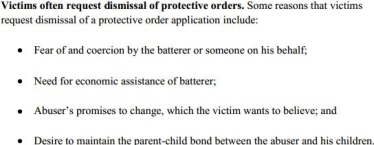

Note that accusers are automatically nominated “victims,” and those they accuse are automatically presumed to be “batterers”/“abusers.”

Judges are told to be suspicious. No benchbook includes “pissed off” as among the motives for procuring a protective order. Acknowledging that allegations may be made impulsively or spitefully is contrary to the conceits of the system.

Women’s advocates, who are sometimes party to restraining order applications, also tend to discourage retractions, because second-guessing discredits “the cause.”

Too often decent people who reconsider impulsive acts succumb to fears of punishment or cruel scrutiny from the system, or fears of alienation or rebukes from friends, family members, or “advisers.” The choice to undo a spiteful whim, which may be  fulfilled in mere minutes, is agonizing.

fulfilled in mere minutes, is agonizing.

The petitioner who knows s/he was guided to apply for a restraining order by motives ulterior to the ones s/he alleged to a judge should even so favor conscience over personal or peripheral interests, because the defendant is certain to be in at least as much agony—and unjustly.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

The first of these important facts is that the nanny state issues restraining orders carelessly, tactlessly, and callously. Their recipients are completely bewildered, and no one actually explains to them what a restraining order signifies, what its specific prohibitions are, or anything else. If a cop is involved, s/he may impress upon a restraining order recipient that the court’s order should be “taken very seriously.” (“What should be taken very seriously?” “The court’s order!”) That’s it. Not one person involved even inquires, for example, whether the restraining order recipient is sighted (as opposed to stone blind), mentally competent, or knows how to read. Restraining orders are casually dispensed (millions of them, each year) and then, unless they’re violated intentionally or accidentally (and motive doesn’t matter; the cops swoop in, regardless), they’re dispensed with: “NEXT!” “NEXT!” “NEXT!” It’s a revolving-door process that’s administered by conveyor belt but enforced with rigorous menace. That’s the first important fact.

The first of these important facts is that the nanny state issues restraining orders carelessly, tactlessly, and callously. Their recipients are completely bewildered, and no one actually explains to them what a restraining order signifies, what its specific prohibitions are, or anything else. If a cop is involved, s/he may impress upon a restraining order recipient that the court’s order should be “taken very seriously.” (“What should be taken very seriously?” “The court’s order!”) That’s it. Not one person involved even inquires, for example, whether the restraining order recipient is sighted (as opposed to stone blind), mentally competent, or knows how to read. Restraining orders are casually dispensed (millions of them, each year) and then, unless they’re violated intentionally or accidentally (and motive doesn’t matter; the cops swoop in, regardless), they’re dispensed with: “NEXT!” “NEXT!” “NEXT!” It’s a revolving-door process that’s administered by conveyor belt but enforced with rigorous menace. That’s the first important fact. My friend Annie has been pulling her hair out and medicating herself to sleep (I’ve done the same since I was falsely accused years ago—god bless Benadryl!). She’s even had to resort to applying to the mayor, a former colleague, for a character reference: this to combat allegations that wouldn’t bear up under the scrutiny of a schnauzer. If she successfully prosecutes her appeal, she’ll have had to forfeit enough money for a decent used car, will be remembered for having unsavory associates, and will be subject to the idle speculations aroused by the phrase restraining order. And even if she’s exculpated in the minds of everyone she knows and has had to share this with, the stigma will linger with her in her own psyche (which will itself be only a shadow of what she’ll have to live with if the judge finds for her accuser). This public shaming promotes alienation, bitterness, and depression (besides an abiding distrust of government).

My friend Annie has been pulling her hair out and medicating herself to sleep (I’ve done the same since I was falsely accused years ago—god bless Benadryl!). She’s even had to resort to applying to the mayor, a former colleague, for a character reference: this to combat allegations that wouldn’t bear up under the scrutiny of a schnauzer. If she successfully prosecutes her appeal, she’ll have had to forfeit enough money for a decent used car, will be remembered for having unsavory associates, and will be subject to the idle speculations aroused by the phrase restraining order. And even if she’s exculpated in the minds of everyone she knows and has had to share this with, the stigma will linger with her in her own psyche (which will itself be only a shadow of what she’ll have to live with if the judge finds for her accuser). This public shaming promotes alienation, bitterness, and depression (besides an abiding distrust of government).