“Court is perfectly suited to the fantasies of someone with a personality disorder: There is an all-powerful person (the judge) who will punish or control the other [person]. The focus of the court process is perceived as fixing blame—and many with personality disorders are experts at blame. There is a professional ally who will champion their cause (their attorney—or if no attorney, the judge) […]. Generally, those with personality disorders are highly skilled at—and invested in—the adversarial process.

“Those with personality disorders often have an intensity that convinces inexperienced professionals—counselors and attorneys—that what they say is true. Their charm, desperation, and drive can reach a high level in this very emotional bonding process with the professional. Yet this intensity is a characteristic of a personality disorder, and is completely independent from the accuracy of their claims.”

—William (Bill) Eddy (1999)

Contemplating these statements by therapist, attorney, and mediator Bill Eddy should make it clear how perfectly the disordered personality and the restraining order click. Realization of the high-conflict person’s fantasies of punishment and control is accomplished as easily as making some false or histrionically hyped allegations in a few-minute interview with a judge.

Contemplating these statements should also make clear the all-but-impossible task that counteracting the fraudulent allegations of high-conflict people can pose, both because disordered personalities lie without compunction and because they’re intensely invested in domination, blaming, and punishment.

Contemplating these statements should also make clear the all-but-impossible task that counteracting the fraudulent allegations of high-conflict people can pose, both because disordered personalities lie without compunction and because they’re intensely invested in domination, blaming, and punishment.

Lying may be justified in their eyes—possibly to bring a reconciliation. (This can be quite convoluted, like the former wife who alleged child sexual abuse so that her ex-husband’s new wife would divorce him and he would return to her—or so she seemed to believe.) Or lying may be justified as a punishment in their eyes.

As Mr. Eddy explains in a related article (2008):

Courts rely heavily on “he said, she said” declarations, signed “under penalty of perjury.” However, a computer search of family law cases published by the appellate courts shows only one appellate case in California involving a penalty for perjury: People v. Berry (1991) 230 Cal. App. 3d 1449. The penalty? Probation.

Perjury is a criminal offense, punishable by fine or jail time, but it must be prosecuted by the District Attorney, who does not have the time. [J]udges have the ability to sanction (fine) parties but no time to truly determine that one party is lying. Instead, they may assume both parties are lying or just weigh their credibility. With no specific consequence, the risks of lying are low.

High-conflict fraudsters, in other words, get away with murder—or at least character assassination (victims of which eat themselves alive). Lying is a compulsion of personality disorders and is typical of high-conflict disordered personalities: borderlines, antisocials, narcissists, and histrionics.

When my own life was derailed eight years ago, I’d never heard the phrase personality disorder. Five years later, when I started this blog, I still hadn’t. My interest wasn’t in comprehension; it was to recover my sanity and cheer so I could return to doing what was dear to me. I’m sure most victims are led to do the same and never begin to comprehend the motives of high-conflict abusers.

I’ve read Freud, Lacan, and some other abstruse psychology texts, because I was trained as a literary analyst, and psychological theories are sometimes used by textual critics as interpretive prisms. None of these equipped me, though, to understand the kind of person who would wantonly lie to police officers and judges, enlist others in smear campaigns, and/or otherwise engage in dedicatedly vicious misconduct.

I’ve read Freud, Lacan, and some other abstruse psychology texts, because I was trained as a literary analyst, and psychological theories are sometimes used by textual critics as interpretive prisms. None of these equipped me, though, to understand the kind of person who would wantonly lie to police officers and judges, enlist others in smear campaigns, and/or otherwise engage in dedicatedly vicious misconduct.

What my collegiate training did provide me with, though, is a faculty for discerning patterns and themes, and it has detected patterns and themes that have been the topics of much of the grudging writing I’ve done in this blog.

Absorbing the explications of psychologists and dispute mediators after having absorbed the stories of many victims of abuse of court process, I’ve repeatedly noticed that the two sources mutually corroborate each other.

Not long ago, I approached the topic of what I called “group-bullying,” because it’s something I’ve been subject to and because many others had reported to me (and continue to report) being subject to the same: sniping by multiple parties, conspiratorial harassment, derision on social media, false reports to employers and rumor-milling, fantastical protestations of fear and apprehension, etc.

The other day, I encountered the word mobbing applied by a psychologist to the same behavior, a word that says the same thing much more crisply.

Quoting Dr. Tara Palmatier (see also the embedded hyperlinks, which I’ve left in):

If you’re reading this, perhaps you’ve been or currently are the Target of Blame of a high-conflict spouse, girlfriend, boyfriend, ex, colleague, boss, or stranger(s). Perhaps you’ve been on the receiving end of mobbing (bullying by a group instigated by one or two ringleaders) and/or a smear campaign or distortion campaign of a high-conflict person who has decided you’re to blame for her or his unhappiness. It’s a horrible position to be in, particularly because high-conflict individuals don’t seem to ever stop their blaming and malicious behaviors.

A perfect correspondence. And what more aptly describes the victim of restraining order abuse than “Target of Blame”?

This phrase in turn is found foremost on the website of the High Conflict Institute, founded by Bill Eddy, whom I opened this post by quoting:

Restraining orders are seldom singled out or fully appreciated for the torture devices they are by those who haven’t been intensively made aware of their unique potential to upturn or trash lives, but the victims who comment on this and other blogs, petitions, and online forums are saying the same things the psychologists and mediators are, and they’re talking about the same perpetrators.

Judges understand blaming. That’s their bailiwick and raison d’être. They may even understand false blaming much better than they let on. What they don’t understand, however, is false blaming as a pathological motive.

Quoting “Strategies and Methods in Mediation and Communication with High Conflict People” by Duncan McLean, which I highlighted in the last post:

Emotionally healthy people base their feelings on facts, whereas people with high conflict personalities tend to bend the facts to fit what they are feeling. This is known as “emotional reasoning.” The facts are not actually true, but they feel true to the individual. The consequence of this is that they exhibit an enduring pattern of blaming others and a need to control and/or manipulate.

There are no more convenient expedients for realizing the compulsions of disordered personalities’ emotional reasoning and will to divert blame from themselves and exert it on others than restraining orders, which assign blame before the targets of that blame even know what hit them.

There are no more convenient expedients for realizing the compulsions of disordered personalities’ emotional reasoning and will to divert blame from themselves and exert it on others than restraining orders, which assign blame before the targets of that blame even know what hit them.

Returning to the concept of “mobbing” (and citing Dr. Palmatier), consider:

The group victimization of a single target has several goals, including demeaning, discrediting, alienating, excluding, humiliating, scapegoating, isolating and, ultimately, eliminating the targeted individual.

Group victimization can be the product of a frenzied horde. But it can also be accomplished by one pathologically manipulative individual…and a judge.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

During the term of their relationship, no reports of any kind of domestic conflict were made to authorities.

During the term of their relationship, no reports of any kind of domestic conflict were made to authorities. back was turned. Since the woman’s knuckles were plainly lacerated from punching glass, no arrest ensued. According to the man’s stepmother, the woman lied similarly to procure a protection order a couple of days later.

back was turned. Since the woman’s knuckles were plainly lacerated from punching glass, no arrest ensued. According to the man’s stepmother, the woman lied similarly to procure a protection order a couple of days later.

The reason why, basically, is that the system likes closure. Once it rules on something, it doesn’t want to think about it again.

The reason why, basically, is that the system likes closure. Once it rules on something, it doesn’t want to think about it again.

Contemplating these statements should also make clear the all-but-impossible task that counteracting the fraudulent allegations of high-conflict people can pose, both because disordered personalities lie without compunction and because they’re intensely invested in domination, blaming, and punishment.

Contemplating these statements should also make clear the all-but-impossible task that counteracting the fraudulent allegations of high-conflict people can pose, both because disordered personalities lie without compunction and because they’re intensely invested in domination, blaming, and punishment. I’ve read Freud, Lacan, and some other abstruse psychology texts, because I was trained as a literary analyst, and psychological theories are sometimes used by textual critics as interpretive prisms. None of these equipped me, though, to understand the kind of person who would wantonly lie to police officers and judges, enlist others in smear campaigns, and/or otherwise engage in dedicatedly vicious misconduct.

I’ve read Freud, Lacan, and some other abstruse psychology texts, because I was trained as a literary analyst, and psychological theories are sometimes used by textual critics as interpretive prisms. None of these equipped me, though, to understand the kind of person who would wantonly lie to police officers and judges, enlist others in smear campaigns, and/or otherwise engage in dedicatedly vicious misconduct.

So enculturated has the belief that women are helpless victims become that no one recognizes that feminist political might is unrivaled—unrivaled—and it’s in the interest of preserving that political might and enhancing it that the belief that women are helpless victims is vigorously promulgated by the feminist establishment that should be promoting the idea that women aren’t helpless.

So enculturated has the belief that women are helpless victims become that no one recognizes that feminist political might is unrivaled—unrivaled—and it’s in the interest of preserving that political might and enhancing it that the belief that women are helpless victims is vigorously promulgated by the feminist establishment that should be promoting the idea that women aren’t helpless. Scholars, members of the clergy, and practitioners of disciplines like medicine, science, and the law, among others from whom we expect scrupulous truthfulness and a contempt for deception, are furthermore no more above lying (or actively or passively abetting fraud) than anyone else.

Scholars, members of the clergy, and practitioners of disciplines like medicine, science, and the law, among others from whom we expect scrupulous truthfulness and a contempt for deception, are furthermore no more above lying (or actively or passively abetting fraud) than anyone else. M.D., Ph.D., Th.D., LL.D.—no one is above lying, and the fact is the better a liar’s credentials are, the more ably s/he expects to and can pull the wool over the eyes of judges, because in the political arena judges occupy, titles carry weight: might makes right.

M.D., Ph.D., Th.D., LL.D.—no one is above lying, and the fact is the better a liar’s credentials are, the more ably s/he expects to and can pull the wool over the eyes of judges, because in the political arena judges occupy, titles carry weight: might makes right.

The 148 search engine terms that appear below—at least one to two dozen of which concern false allegations—are ones that brought readers to this blog between the hours of 12 a.m. and 7:21 p.m. yesterday (and don’t include an additional 49 “unknown search terms”).

The 148 search engine terms that appear below—at least one to two dozen of which concern false allegations—are ones that brought readers to this blog between the hours of 12 a.m. and 7:21 p.m. yesterday (and don’t include an additional 49 “unknown search terms”).

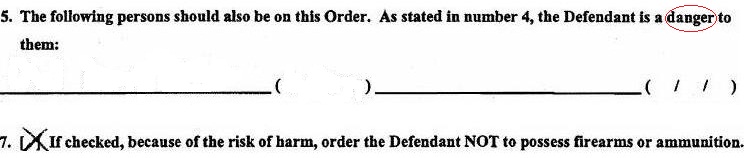

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

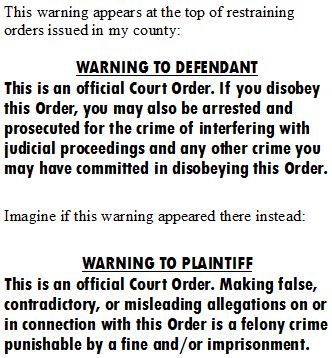

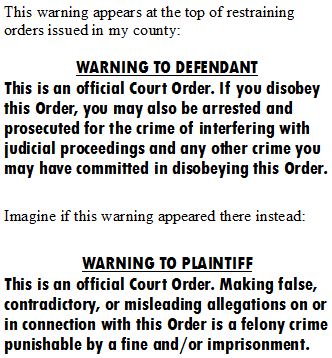

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.