“False allegations and bogus calls to the police are an extremely sick form of abuse.”

—Tara J. Palmatier, Psy.D.

I introduced a useful term in my previous post coined by psychologist Jennifer Freyd and adapted by psychologist Tara Palmatier to her own practice and professional writing: DARVO, an acronym of Deny, Attack, and Reverse Victim and Offender.

In sum, the abuser in a relationship denies a behavior s/he’s called on, attacks his or her confronter (the victim of the behavior), and by social manipulation (including false allegations, hysterical protestations, smear tactics, etc.) reverses roles with him or her: the batterer becomes the beaten, the stalker becomes the stalked, the sexual harasser becomes the sexually harassed, etc.

The restraining order process and DARVO are a jigsaw-puzzle fit, because the first party up the courthouse steps is recognized as the victim, that party’s representations are accepted as “the truth,” a restraining order is easily got with a little dramatic legerdemain, and procurement of a restraining order instantly qualifies its plaintiff as the victim and its defendant as the villain in the eyes of nearly everybody. In one fell swoop, the exploiter dodges accountability for his or her misconduct and punishes his or her victim for being intolerant of that misconduct.

To illustrate, a conjectural case in point:

Imagine that a solitary, bookish man, a starving but striving artist working on a project for children, haplessly attracts a group of overeducated and neglected women keen for recognition and attention. Their leader, a brassy, charismatic, married woman, works her wiles on the man to indulge an infatuation, contriving reasons to hang around his house up to and past midnight. He lives remotely, and the secluding darkness and intimacy are delicious and allow the woman to step out of the strictures of her daytime life as easily as she slips off her wedding ring and mutes her cellphone.

Her coterie of girlfriends is transposed straight from the halls of high school. They’re less physically favored than the leader of their pack and content to warm themselves in her aura. The adolescent intrigue injects some color into their treadmill lives, and they savor the vicarious thrill of the hunt. The man is a topic of their daily conversation. The women feel young again for a few months, like conspirators in an unconsummated teen crush.

Her coterie of girlfriends is transposed straight from the halls of high school. They’re less physically favored than the leader of their pack and content to warm themselves in her aura. The adolescent intrigue injects some color into their treadmill lives, and they savor the vicarious thrill of the hunt. The man is a topic of their daily conversation. The women feel young again for a few months, like conspirators in an unconsummated teen crush.

Eventually, however, the creeping finger of consequence insinuates itself between the pages of the women’s Harlequin-novel holiday, and the game is a lark no more. Realizing the ruse can’t be maintained indefinitely, the married woman abruptly vanishes, and her cronies return where they came from like shadows retreating from the noonday sun.

What no one knows can’t hurt them.

The man, though, nevertheless learns of the deception and confronts the woman in a letter, asking her to meet with him so he can understand her motives and gain some closure. The woman denies understanding the source of his perplexity and represents him (to himself) as a stalker. She then proceeds to represent him as such to her peers at his former place of work and then to her husband, the police, and the court over a period of days and weeks. She publicly alleges the man sexually harassed her, is dangerous, and poses a threat to her and her spouse, and to her friends and family.

Her co-conspirators passively play along. It’s easy: out of sight, out of mind.

The life of the man who’d hospitably welcomed the strangers, shaking hands in good faith and doling out mugs of cheer, is trashed: multiple trips to the police precinct to answer false charges and appeals to the court that only invite censure and further abuse. His record, formerly that of an invisible man, becomes hopelessly corrupted. His artistic endeavor, a labor of love that he’d plied himself at for years and on which he’d banked his future joy and financial comfort, is predictably derailed.

The life of the man who’d hospitably welcomed the strangers, shaking hands in good faith and doling out mugs of cheer, is trashed: multiple trips to the police precinct to answer false charges and appeals to the court that only invite censure and further abuse. His record, formerly that of an invisible man, becomes hopelessly corrupted. His artistic endeavor, a labor of love that he’d plied himself at for years and on which he’d banked his future joy and financial comfort, is predictably derailed.

The women blithely return to realizing their ambitions while the man’s life frays and tatters.

Sleepless years go by, the economy tanks, and the man flails to simply keep afloat. The paint flakes on his house and his hopes. His health deteriorates to the extent that he’s daily in physical pain. He finally employs an attorney to craft a letter, pointlessly, undertakes a lawsuit on his own, too late, and maunders on like this, alternately despairing and taking one stab or another at recovering his life and resuscitating his dreams.

The married woman monitors him meanwhile, continuing to represent him as a stalker, both strategically and randomly to titillate and arouse attention, while accruing evidence for a further prosecution, and bides her time until the statute of limitation for her frauds on the court lapses to ensure that she’s immune from the risk of punishment. A little over seven years to the day of her making her original allegations, she takes the man to court all over again, enlisting the ready cooperation of one of her former confederates, to nail the coffin shut.

This is DARVO at its most dedicated and devotional, and it’s pure deviltry and exemplifies the dire effects and havoc potentially wrought by a court process that’s easily and freely exploited and indifferently administered.

In her explication of DARVO, Dr. Palmatier introduces this quotation from attorney and mediator William (Bill) Eddy: “It’s only the Persuasive Blamers of Cluster B [see footnote] who keep high-conflict disputes going. They are persuasive, and to keep the focus off their own behavior (the major source of the problem), they get others to join in the blaming.” As a scenario like the one I’ve posited above illustrates, persuasive blame-shifters may keep high-conflict clashes going for years, clashes that in their enlistment of others verge on lynch-mobbing that includes viral and virulent name-calling and public denigration.

Consider the origins of consequences that cripple lives and can potentially lead to physical violence, including suicide or even homicide, and then consider whether our courts should be the convenient tools of such ends. Absent our courts’ availability as media of malice, the appetite of the practitioner of DARVO would starvo.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

Dr. Tara Palmatier: “Cluster B disorders include histrionic personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, narcissistic personality disorder, and antisocial personality disorder. At their core, I believe all Cluster B disorders stem from sociopathy (i.e., lack of empathy for others, refusal to hold themselves accountable for their behaviors, and exploitation of others). Bleiberg (2001) refers to these characterological disorders as ‘severe,’ because they chronically engage in extreme conflict [and] drama, and cause the most problems in society.”

Scholars, members of the clergy, and practitioners of disciplines like medicine, science, and the law, among others from whom we expect scrupulous truthfulness and a contempt for deception, are furthermore no more above lying (or actively or passively abetting fraud) than anyone else.

Scholars, members of the clergy, and practitioners of disciplines like medicine, science, and the law, among others from whom we expect scrupulous truthfulness and a contempt for deception, are furthermore no more above lying (or actively or passively abetting fraud) than anyone else. M.D., Ph.D., Th.D., LL.D.—no one is above lying, and the fact is the better a liar’s credentials are, the more ably s/he expects to and can pull the wool over the eyes of judges, because in the political arena judges occupy, titles carry weight: might makes right.

M.D., Ph.D., Th.D., LL.D.—no one is above lying, and the fact is the better a liar’s credentials are, the more ably s/he expects to and can pull the wool over the eyes of judges, because in the political arena judges occupy, titles carry weight: might makes right. The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin I’ve quoted goes on at some length to detail the difficulties and complexities that unraveling false claims entails for agents of the FBI. Appreciate then how absurd is the state’s faith that a single judge—or a couple of them—can ascertain the truth of civil restraining order allegations by auditing claims in a hearing or hearings arrived at with no prior information, that last mere minutes, and that are furthermore biased by the preconception that the accused is guilty.

The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin I’ve quoted goes on at some length to detail the difficulties and complexities that unraveling false claims entails for agents of the FBI. Appreciate then how absurd is the state’s faith that a single judge—or a couple of them—can ascertain the truth of civil restraining order allegations by auditing claims in a hearing or hearings arrived at with no prior information, that last mere minutes, and that are furthermore biased by the preconception that the accused is guilty. The very real if inconvenient truth remains that victims of false allegations made to authorities and the courts present with the same symptoms highlighted in the epigraph: “fear, anxiety, nervousness, self-blame, anger, shame, and difficulty sleeping”—among a host of others. And that’s just the ones who aren’t robbed of everything that made their lives meaningful, including home, property, and family. In the latter case, post-traumatic stress disorder may be the least of their torments. They may be left homeless, penniless, childless, and emotionally scarred.

The very real if inconvenient truth remains that victims of false allegations made to authorities and the courts present with the same symptoms highlighted in the epigraph: “fear, anxiety, nervousness, self-blame, anger, shame, and difficulty sleeping”—among a host of others. And that’s just the ones who aren’t robbed of everything that made their lives meaningful, including home, property, and family. In the latter case, post-traumatic stress disorder may be the least of their torments. They may be left homeless, penniless, childless, and emotionally scarred.

In fact, what it and any number of others’ ordeals show is that when you offer people an easy means to excite drama and conflict, they’ll exploit it.

In fact, what it and any number of others’ ordeals show is that when you offer people an easy means to excite drama and conflict, they’ll exploit it. Her coterie of girlfriends is transposed straight from the halls of high school. They’re less physically favored than the leader of their pack and content to warm themselves in her aura. The adolescent intrigue injects some color into their treadmill lives, and they savor the vicarious thrill of the hunt. The man is a topic of their daily conversation. The women feel young again for a few months, like conspirators in an unconsummated teen crush.

Her coterie of girlfriends is transposed straight from the halls of high school. They’re less physically favored than the leader of their pack and content to warm themselves in her aura. The adolescent intrigue injects some color into their treadmill lives, and they savor the vicarious thrill of the hunt. The man is a topic of their daily conversation. The women feel young again for a few months, like conspirators in an unconsummated teen crush. The life of the man who’d hospitably welcomed the strangers, shaking hands in good faith and doling out mugs of cheer, is trashed: multiple trips to the police precinct to answer false charges and appeals to the court that only invite censure and further abuse. His record, formerly that of an invisible man, becomes hopelessly corrupted. His artistic endeavor, a labor of love that he’d plied himself at for years and on which he’d banked his future joy and financial comfort, is predictably derailed.

The life of the man who’d hospitably welcomed the strangers, shaking hands in good faith and doling out mugs of cheer, is trashed: multiple trips to the police precinct to answer false charges and appeals to the court that only invite censure and further abuse. His record, formerly that of an invisible man, becomes hopelessly corrupted. His artistic endeavor, a labor of love that he’d plied himself at for years and on which he’d banked his future joy and financial comfort, is predictably derailed. A man eyes a younger, attractive woman at work every day. She’s impressed by him, also, and reciprocates his interest. They have a brief sexual relationship that, unknown to her, is actually an extramarital affair, because the man is married. The younger woman, having naïvely trusted him, is crushed when the man abruptly drops her, possibly cruelly, and she then discovers he has a wife. Maybe she openly confronts him at work. Maybe she calls or texts him. Maybe repeatedly. The man, concerned to preserve appearances and his marriage, applies for a restraining order alleging the woman is harassing him, has become fixated on him, is unhinged. As evidence, he provides phone records, possibly dating from the beginning of the affair—or pre-dating it—besides intimate texts and emails. He may also provide tokens of affection she’d given him, like a birthday card the woman signed and other romantic trifles, and represent them as unwanted or even (implicitly) disturbing. “I’m a married man, Your Honor,” he testifies, admitting nothing, “and this woman’s conduct is threatening my marriage, besides my status at work.”

A man eyes a younger, attractive woman at work every day. She’s impressed by him, also, and reciprocates his interest. They have a brief sexual relationship that, unknown to her, is actually an extramarital affair, because the man is married. The younger woman, having naïvely trusted him, is crushed when the man abruptly drops her, possibly cruelly, and she then discovers he has a wife. Maybe she openly confronts him at work. Maybe she calls or texts him. Maybe repeatedly. The man, concerned to preserve appearances and his marriage, applies for a restraining order alleging the woman is harassing him, has become fixated on him, is unhinged. As evidence, he provides phone records, possibly dating from the beginning of the affair—or pre-dating it—besides intimate texts and emails. He may also provide tokens of affection she’d given him, like a birthday card the woman signed and other romantic trifles, and represent them as unwanted or even (implicitly) disturbing. “I’m a married man, Your Honor,” he testifies, admitting nothing, “and this woman’s conduct is threatening my marriage, besides my status at work.”

Victims of false allegations made on restraining orders may be labeled “stalker,” “batterer,” “sicko,” “sexual harasser,” “child-abuser,” “whore,” or even “rapist”—publicly and permanently—by accusers whose sole motive is to brutalize. And agents of these victims’ own government(s) arbitrarily authorize this bullying and may baselessly and basely participate in it, compounding the injury exponentially.

Victims of false allegations made on restraining orders may be labeled “stalker,” “batterer,” “sicko,” “sexual harasser,” “child-abuser,” “whore,” or even “rapist”—publicly and permanently—by accusers whose sole motive is to brutalize. And agents of these victims’ own government(s) arbitrarily authorize this bullying and may baselessly and basely participate in it, compounding the injury exponentially.

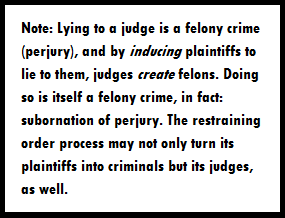

Many restraining order recipients are brought to this site wondering how to recover damages for false allegations and the torments and losses that result from them. Not only is perjury (lying to the court) never prosecuted; it’s never explicitly acknowledged. The question arises whether false accusers

Many restraining order recipients are brought to this site wondering how to recover damages for false allegations and the torments and losses that result from them. Not only is perjury (lying to the court) never prosecuted; it’s never explicitly acknowledged. The question arises whether false accusers  I understand her very well, but at the risk of pointing out the obvious, she shouldn’t have to. False allegations aren’t a withered limb, a ruptured disc, or an autoimmune disease. These latter things are real and unavoidable. Lies aren’t real, and their pain is easily relieved. The lies just have to be rectified.

I understand her very well, but at the risk of pointing out the obvious, she shouldn’t have to. False allegations aren’t a withered limb, a ruptured disc, or an autoimmune disease. These latter things are real and unavoidable. Lies aren’t real, and their pain is easily relieved. The lies just have to be rectified.

Playing the victim is a very potent form of passive aggression when the audience includes authorities and judges. Validation from these audience members is particularly gratifying to the egos of frauds, and both the police and judges have been trained to respond gallantly to the appeals of “damsels in distress.”

Playing the victim is a very potent form of passive aggression when the audience includes authorities and judges. Validation from these audience members is particularly gratifying to the egos of frauds, and both the police and judges have been trained to respond gallantly to the appeals of “damsels in distress.” One of the aforementioned teachers was on his way to Nashville to become a songwriter, that is, a creative artist. Any career in the public eye like this one is vulnerable to being compromised or trashed by a scandal that may be based on nothing but cunning lies or a disturbed person’s fantasies spewed impulsively in a window of five or 10 minutes. Besides the obvious impairment that something like this can exert on income prospects, its psychological effects alone can make performance of a job impossible. And nothing kills income prospects more surely than that.

One of the aforementioned teachers was on his way to Nashville to become a songwriter, that is, a creative artist. Any career in the public eye like this one is vulnerable to being compromised or trashed by a scandal that may be based on nothing but cunning lies or a disturbed person’s fantasies spewed impulsively in a window of five or 10 minutes. Besides the obvious impairment that something like this can exert on income prospects, its psychological effects alone can make performance of a job impossible. And nothing kills income prospects more surely than that.

“If we did prosecute perjurers, there’d be no resources left for putting dangerous people behind bars…so we’ll prosecute the people perjurers falsely accuse of being dangerous”—as analysis of most of the arguments made in defense of domestic violence and restraining order policies reveals, the reasoning is circular and smells foul. It’s in fact unreasoned “reasoning” that’s really just something to say to distract attention from unflattering truths that don’t win elections, federal grants, popular esteem, or political favor. So entrenched are these policies and so megalithic (and lucrative) that rhetoric like this actually passes for satisfactory when it’s used by someone in a crisp suit with a crisper title.

“If we did prosecute perjurers, there’d be no resources left for putting dangerous people behind bars…so we’ll prosecute the people perjurers falsely accuse of being dangerous”—as analysis of most of the arguments made in defense of domestic violence and restraining order policies reveals, the reasoning is circular and smells foul. It’s in fact unreasoned “reasoning” that’s really just something to say to distract attention from unflattering truths that don’t win elections, federal grants, popular esteem, or political favor. So entrenched are these policies and so megalithic (and lucrative) that rhetoric like this actually passes for satisfactory when it’s used by someone in a crisp suit with a crisper title. The restraining order process has become a perfunctory routine verging on a skit, a scripted pas de deux between a judge and a complainant. Exposure of the iniquity of this procedural farce hardly requires commentary.

The restraining order process has become a perfunctory routine verging on a skit, a scripted pas de deux between a judge and a complainant. Exposure of the iniquity of this procedural farce hardly requires commentary. The answer to these questions is of course known to (besides men) any number of women who’ve been victimized by the restraining order process. They’re not politicians, though. Or members of the ivory-tower club that determines the course of what we call mainstream feminism. They’re just the people who actually know what they’re talking about, because they’ve been broken by the state like butterflies pinned to a board and slowly vivisected with a nickel by a sadistic child.

The answer to these questions is of course known to (besides men) any number of women who’ve been victimized by the restraining order process. They’re not politicians, though. Or members of the ivory-tower club that determines the course of what we call mainstream feminism. They’re just the people who actually know what they’re talking about, because they’ve been broken by the state like butterflies pinned to a board and slowly vivisected with a nickel by a sadistic child. In case you were wondering—and since you’re here, you probably were—there is no gaining relief from false allegations on a civil restraining order. Repetition for emphasis: There is no gaining relief from false allegations on a civil restraining order. Why? Because as far as the court’s concerned, there are no such things.

In case you were wondering—and since you’re here, you probably were—there is no gaining relief from false allegations on a civil restraining order. Repetition for emphasis: There is no gaining relief from false allegations on a civil restraining order. Why? Because as far as the court’s concerned, there are no such things. Many of the respondents to this blog are the victims of collisions like this. Some anomalous moral zero latched onto them, duped them, exploited them, even assaulted them and then turned the table and misrepresented them to the police and the courts as a stalker, harasser, or brute to compound the injury. Maybe for kicks, maybe for “payback,” maybe to cover his or her tread marks, maybe to get fresh attention at his or her victim’s expense, or maybe for no motive a normal mind can hope to accurately interpret.

Many of the respondents to this blog are the victims of collisions like this. Some anomalous moral zero latched onto them, duped them, exploited them, even assaulted them and then turned the table and misrepresented them to the police and the courts as a stalker, harasser, or brute to compound the injury. Maybe for kicks, maybe for “payback,” maybe to cover his or her tread marks, maybe to get fresh attention at his or her victim’s expense, or maybe for no motive a normal mind can hope to accurately interpret. The phrase restraining order fraud, too, needs to gain more popular currency, and I encourage anyone who’s been victimized by false allegations to employ it. Fraud in its most general sense is willful misrepresentation intended to mislead for the purpose of realizing some source of gratification. As fraud is generally understood in law, that gratification is monetary. It may, however, derive from any number of alternative sources, including attention and revenge, two common motives for restraining order abuse. The goal of fraud on the courts is success (toward gaining, for example, attention or revenge).

The phrase restraining order fraud, too, needs to gain more popular currency, and I encourage anyone who’s been victimized by false allegations to employ it. Fraud in its most general sense is willful misrepresentation intended to mislead for the purpose of realizing some source of gratification. As fraud is generally understood in law, that gratification is monetary. It may, however, derive from any number of alternative sources, including attention and revenge, two common motives for restraining order abuse. The goal of fraud on the courts is success (toward gaining, for example, attention or revenge).