One of my favorite puzzles when I was a boy directed the solver to figure out what was different between almost identical pictures. I think it appeared in Highlights for Children. I have a collection of Highlights someplace, because I meant to write for kids and used to study and practice children’s writing daily, but I haven’t looked at them in years.

I’m reminded of this, because, as you might have discerned, one among the epithets in this post’s title is distinct from the others: fag.

I’m reminded of this, because, as you might have discerned, one among the epithets in this post’s title is distinct from the others: fag.

When I was growing up, I knew a very simple boy who was singled out at an early age—nine or thereabouts—and routinely ridiculed by the “cool” boys at school. Some girls occasionally joined in, too, albeit half-heartedly, to curry favor with boys they wanted to like them. “Fag!” or “Faggot!” was a favored insult among schoolboys. No other had anything close to its heft as a term of contempt to pierce a man-child to the bone.

The boy I’m recalling happened to be Polish, and Polack was a competing term of derision that might have conveniently been used to hurt him. It didn’t rouse nearly as much pack frenzy, though. His name started with F, besides, so its pairing with fag was poetic kismet. “Fag!” followed this boy from grade to grade like a toxic echo. It was how he was greeted, and he would sometimes mince, affect limp wrists, and swipe at the other boys, because it amused them and won him attention and the closest thing to membership he could hope for.

The boy wasn’t gay; he was just easy meat to sate the bloodlust of cruel kids.

The last time I saw him was when I was a young adult. He was panhandling outside of a drugstore for diaper money. He’d apparently gotten a girl pregnant right out of high school to prove his virility. The abuses to which he’d been relentlessly subjected determined the arc of his life.

I relate this story in the context of restraining order abuse to highlight the grave effects of public humiliation and revilement. Labeling of this sort isn’t just tormenting and alienating but destructive. It corrupts the mind, silently and sinuously. It confounds ambitions, erodes trust, and hobbles lives.

Victims of false allegations made on restraining orders may be labeled “stalker,” “batterer,” “sicko,” “sexual harasser,” “child-abuser,” “whore,” or even “rapist”—publicly and permanently—by accusers whose sole motive is to brutalize. And agents of these victims’ own government(s) arbitrarily authorize this bullying and may baselessly and basely participate in it, compounding the injury exponentially.

Victims of false allegations made on restraining orders may be labeled “stalker,” “batterer,” “sicko,” “sexual harasser,” “child-abuser,” “whore,” or even “rapist”—publicly and permanently—by accusers whose sole motive is to brutalize. And agents of these victims’ own government(s) arbitrarily authorize this bullying and may baselessly and basely participate in it, compounding the injury exponentially.

I’ve been contacted by people who’ve either been explicitly or implicitly branded with one or several of these labels. Falsely and maliciously. I’ve been branded with more than one myself, and these epithets have been repeatedly used with and among people I don’t even know. For many years. Even at one of my former places of work. And there’s f* all I can do about it, legally.

Labels like these, even when perceived as false by judges, aren’t scrupulously scrubbed away. Resisting them, furthermore, simply invites the application of more of the same. Judges’ turning a blind eye to them, what’s more than that, authorizes their continuously being used with impunity, as the boys in the story I shared used the word fag. Victims of false allegations report being in therapy, being on meds for psychological disturbances like depression and insomnia, leaving or losing jobs—sometimes serially—and entertaining homicidal thoughts and even acting on suicidal ones.

No standard of proof is applied to labels scribbled or check-marked on restraining orders, which to malicious accusers are the documentary equivalents of toilet stalls begging for graffiti.

That the courts may only enable bullying, taunting, and humiliation is no defense, nor is “policy.” Adding muscle to malice is hardly blameless. Anyone occupying a position of public trust who abets this kind of brutality, actively or passively, knowingly or carelessly, should be removed, whether a judge, a police officer, or other government official, agent, or employee.

This hateful misconduct is bad enough when it originates on the playground.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

Many restraining order recipients are brought to this site wondering how to recover damages for false allegations and the torments and losses that result from them. Not only is perjury (lying to the court) never prosecuted; it’s never explicitly acknowledged. The question arises whether false accusers

Many restraining order recipients are brought to this site wondering how to recover damages for false allegations and the torments and losses that result from them. Not only is perjury (lying to the court) never prosecuted; it’s never explicitly acknowledged. The question arises whether false accusers  I understand her very well, but at the risk of pointing out the obvious, she shouldn’t have to. False allegations aren’t a withered limb, a ruptured disc, or an autoimmune disease. These latter things are real and unavoidable. Lies aren’t real, and their pain is easily relieved. The lies just have to be rectified.

I understand her very well, but at the risk of pointing out the obvious, she shouldn’t have to. False allegations aren’t a withered limb, a ruptured disc, or an autoimmune disease. These latter things are real and unavoidable. Lies aren’t real, and their pain is easily relieved. The lies just have to be rectified.

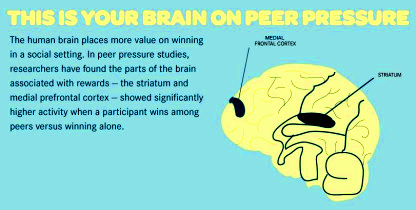

Playing the victim is a very potent form of passive aggression when the audience includes authorities and judges. Validation from these audience members is particularly gratifying to the egos of frauds, and both the police and judges have been trained to respond gallantly to the appeals of “damsels in distress.”

Playing the victim is a very potent form of passive aggression when the audience includes authorities and judges. Validation from these audience members is particularly gratifying to the egos of frauds, and both the police and judges have been trained to respond gallantly to the appeals of “damsels in distress.” One of the aforementioned teachers was on his way to Nashville to become a songwriter, that is, a creative artist. Any career in the public eye like this one is vulnerable to being compromised or trashed by a scandal that may be based on nothing but cunning lies or a disturbed person’s fantasies spewed impulsively in a window of five or 10 minutes. Besides the obvious impairment that something like this can exert on income prospects, its psychological effects alone can make performance of a job impossible. And nothing kills income prospects more surely than that.

One of the aforementioned teachers was on his way to Nashville to become a songwriter, that is, a creative artist. Any career in the public eye like this one is vulnerable to being compromised or trashed by a scandal that may be based on nothing but cunning lies or a disturbed person’s fantasies spewed impulsively in a window of five or 10 minutes. Besides the obvious impairment that something like this can exert on income prospects, its psychological effects alone can make performance of a job impossible. And nothing kills income prospects more surely than that. Although men regularly abuse the restraining order process, it’s more likely that tag-team offensives will be by women against men. Women may be goaded on by their parents or siblings, by authorities, by girlfriends, or by dogmatic women’s advocates. The expression of discontentment with a partner may be regarded as grounds enough for exploiting the system to gain a dominant position. These women may feel obligated to follow through to appease peer or social expectations. Or they may feel pumped up enough by peer or social support to follow through on a spiteful impulse. Girlfriends’ responding sympathetically, whether to claims of quarreling with a spouse or boy- or girlfriend or to claims that are clearly hysterical or even preposterous, is both a natural female inclination and one that may steel a false or frivolous complainant’s resolve.

Although men regularly abuse the restraining order process, it’s more likely that tag-team offensives will be by women against men. Women may be goaded on by their parents or siblings, by authorities, by girlfriends, or by dogmatic women’s advocates. The expression of discontentment with a partner may be regarded as grounds enough for exploiting the system to gain a dominant position. These women may feel obligated to follow through to appease peer or social expectations. Or they may feel pumped up enough by peer or social support to follow through on a spiteful impulse. Girlfriends’ responding sympathetically, whether to claims of quarreling with a spouse or boy- or girlfriend or to claims that are clearly hysterical or even preposterous, is both a natural female inclination and one that may steel a false or frivolous complainant’s resolve.

“If we did prosecute perjurers, there’d be no resources left for putting dangerous people behind bars…so we’ll prosecute the people perjurers falsely accuse of being dangerous”—as analysis of most of the arguments made in defense of domestic violence and restraining order policies reveals, the reasoning is circular and smells foul. It’s in fact unreasoned “reasoning” that’s really just something to say to distract attention from unflattering truths that don’t win elections, federal grants, popular esteem, or political favor. So entrenched are these policies and so megalithic (and lucrative) that rhetoric like this actually passes for satisfactory when it’s used by someone in a crisp suit with a crisper title.

“If we did prosecute perjurers, there’d be no resources left for putting dangerous people behind bars…so we’ll prosecute the people perjurers falsely accuse of being dangerous”—as analysis of most of the arguments made in defense of domestic violence and restraining order policies reveals, the reasoning is circular and smells foul. It’s in fact unreasoned “reasoning” that’s really just something to say to distract attention from unflattering truths that don’t win elections, federal grants, popular esteem, or political favor. So entrenched are these policies and so megalithic (and lucrative) that rhetoric like this actually passes for satisfactory when it’s used by someone in a crisp suit with a crisper title. The restraining order process has become a perfunctory routine verging on a skit, a scripted pas de deux between a judge and a complainant. Exposure of the iniquity of this procedural farce hardly requires commentary.

The restraining order process has become a perfunctory routine verging on a skit, a scripted pas de deux between a judge and a complainant. Exposure of the iniquity of this procedural farce hardly requires commentary. The answer to these questions is of course known to (besides men) any number of women who’ve been victimized by the restraining order process. They’re not politicians, though. Or members of the ivory-tower club that determines the course of what we call mainstream feminism. They’re just the people who actually know what they’re talking about, because they’ve been broken by the state like butterflies pinned to a board and slowly vivisected with a nickel by a sadistic child.

The answer to these questions is of course known to (besides men) any number of women who’ve been victimized by the restraining order process. They’re not politicians, though. Or members of the ivory-tower club that determines the course of what we call mainstream feminism. They’re just the people who actually know what they’re talking about, because they’ve been broken by the state like butterflies pinned to a board and slowly vivisected with a nickel by a sadistic child. In case you were wondering—and since you’re here, you probably were—there is no gaining relief from false allegations on a civil restraining order. Repetition for emphasis: There is no gaining relief from false allegations on a civil restraining order. Why? Because as far as the court’s concerned, there are no such things.

In case you were wondering—and since you’re here, you probably were—there is no gaining relief from false allegations on a civil restraining order. Repetition for emphasis: There is no gaining relief from false allegations on a civil restraining order. Why? Because as far as the court’s concerned, there are no such things. Many of the respondents to this blog are the victims of collisions like this. Some anomalous moral zero latched onto them, duped them, exploited them, even assaulted them and then turned the table and misrepresented them to the police and the courts as a stalker, harasser, or brute to compound the injury. Maybe for kicks, maybe for “payback,” maybe to cover his or her tread marks, maybe to get fresh attention at his or her victim’s expense, or maybe for no motive a normal mind can hope to accurately interpret.

Many of the respondents to this blog are the victims of collisions like this. Some anomalous moral zero latched onto them, duped them, exploited them, even assaulted them and then turned the table and misrepresented them to the police and the courts as a stalker, harasser, or brute to compound the injury. Maybe for kicks, maybe for “payback,” maybe to cover his or her tread marks, maybe to get fresh attention at his or her victim’s expense, or maybe for no motive a normal mind can hope to accurately interpret. The phrase restraining order fraud, too, needs to gain more popular currency, and I encourage anyone who’s been victimized by false allegations to employ it. Fraud in its most general sense is willful misrepresentation intended to mislead for the purpose of realizing some source of gratification. As fraud is generally understood in law, that gratification is monetary. It may, however, derive from any number of alternative sources, including attention and revenge, two common motives for restraining order abuse. The goal of fraud on the courts is success (toward gaining, for example, attention or revenge).

The phrase restraining order fraud, too, needs to gain more popular currency, and I encourage anyone who’s been victimized by false allegations to employ it. Fraud in its most general sense is willful misrepresentation intended to mislead for the purpose of realizing some source of gratification. As fraud is generally understood in law, that gratification is monetary. It may, however, derive from any number of alternative sources, including attention and revenge, two common motives for restraining order abuse. The goal of fraud on the courts is success (toward gaining, for example, attention or revenge). Consider: If someone falsely circulates that you’re a sexual harasser, stalker, and/or violent threat—possibly endangering your employment, to say nothing of savaging you psychologically—you can report that person to the police, seek a restraining order against that person for harassment, and/or sue that person for defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress. If, however, that person first obtains a restraining order against you based on the same false allegations—which is simply a matter of filling out a form and lying to a judge for five or 10 minutes—s/he can then circulate those allegations, which have been officially recognized as legitimate on an order of the court, with impunity. Your credibility, both among colleagues, perhaps, as well as with authorities and the courts, is instantly shot. You may, besides, be subject to police interference based on further false allegations, or even jailed (arrest for violation of a restraining order doesn’t require that the arresting officer actually witness or have incontrovertible proof of anything). And if you are arrested, your credibility is so hopelessly compromised that a false accuser can successfully continue a campaign of harassment indefinitely. Not only that, s/he can expect to do so with the solicitous support and approval of all those who recognize him or her as a “victim” (which may be practically everyone).

Consider: If someone falsely circulates that you’re a sexual harasser, stalker, and/or violent threat—possibly endangering your employment, to say nothing of savaging you psychologically—you can report that person to the police, seek a restraining order against that person for harassment, and/or sue that person for defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress. If, however, that person first obtains a restraining order against you based on the same false allegations—which is simply a matter of filling out a form and lying to a judge for five or 10 minutes—s/he can then circulate those allegations, which have been officially recognized as legitimate on an order of the court, with impunity. Your credibility, both among colleagues, perhaps, as well as with authorities and the courts, is instantly shot. You may, besides, be subject to police interference based on further false allegations, or even jailed (arrest for violation of a restraining order doesn’t require that the arresting officer actually witness or have incontrovertible proof of anything). And if you are arrested, your credibility is so hopelessly compromised that a false accuser can successfully continue a campaign of harassment indefinitely. Not only that, s/he can expect to do so with the solicitous support and approval of all those who recognize him or her as a “victim” (which may be practically everyone). The sad and disgusting fact is that success in the courts, particularly in the drive-thru arena of restraining order prosecution, is largely about impressions. Ask yourself who’s likelier to make the more impressive showing: the liar who’s free to let his or her imagination run wickedly rampant or the honest person who’s constrained by ethics to be faithful to the facts?

The sad and disgusting fact is that success in the courts, particularly in the drive-thru arena of restraining order prosecution, is largely about impressions. Ask yourself who’s likelier to make the more impressive showing: the liar who’s free to let his or her imagination run wickedly rampant or the honest person who’s constrained by ethics to be faithful to the facts?