I started to include the contents of this post in the last one, “Why More Falsely Accused Don’t Speak Out.” Then I thought the topic of angry white men might be due some room of its own.

I started to include the contents of this post in the last one, “Why More Falsely Accused Don’t Speak Out.” Then I thought the topic of angry white men might be due some room of its own.

The previous post outlined reasons why men and women who’ve been victimized by false accusations and procedural abuse are subdued from voicing their outrage publicly. This post criticizes how victims who have expressed their pain and fury have been perceived and treated.

What complaints have emerged in the past couple of decades have been derogated as the rants of “angry white men” (Google this phrase, and you’ll see what I mean; it’s even the title of a 2014 book). Complaints have been dismissed, that is, as nothing worthier of consideration than the cranky kvetches of the disenfranchised “patriarchy,” yesterday’s top dogs said to resent their loss of dominion.

What members of angry white men’s and fathers’ groups are said to object to really is not their being unjustly vilified, kicked to the curb, impoverished, and stripped of roles in their children’s lives (pfft) but their loss of power and status.

It’s an attractively tidy idea and syncs up with feminist dogma nicely, but it’s critically shallow, besides ethically and empathically vacuous.

It’s an attractively tidy idea and syncs up with feminist dogma nicely, but it’s critically shallow, besides ethically and empathically vacuous.

One thing the conclusion ignores is culture. Consider the Jews you may know, or the Koreans or the Pakistanis. Do you reckon restraining orders, for example, or domestic abuse allegations are as commonly brought against Jews or East Asians as they are against whites? Would the action be as countenanced in these ethnic communities, whose members may be more accountable to the judgment of other members and whose community conscience may forbid the public airing of familial discord?

Now it could be true that entitled white men, as members of the patriarchy or former patriarchy, are meaner and feel freer to be abusive than Jews and East Asians. Certainly that’s arguable, but it’s not necessarily arguable on the basis of reports of abuse, because it could also be true that entitled white women, as the usurpers of patriarchy (and as white women), feel freer to exploit feminine advantage and cry wolf than Jews and East Asians do.

Consider that feminism—the origin of the characterization angry white men—is criticized even within its ranks as ethnocentric, i.e., Whitey McWhite. If white women are those who are preponderantly pro-litigation, thanks to white feminist indoctrination into the culture of victimhood and “empowerment,” then who would you expect to be a majority of the targets of procedural abuse?

Those who posit that complainants of courthouse dirty dealings are predominately angry white men aren’t necessarily wrong, but they may be right for reasons they haven’t considered.

Those who posit that complainants of courthouse dirty dealings are predominately angry white men aren’t necessarily wrong, but they may be right for reasons they haven’t considered.

Another one of these reasons is entitlement.

Has it occurred to them, I wonder, that only white people may feel entitled to complain publicly? Do they really imagine that certain minorities aren’t that much more vulnerable to legal abuse, or that they’re not invisible and mute because of their self-perceived or actual lack of entitlement? People who’ve traditionally been the system’s goats aren’t people eager to stick their necks out. They never had faith in social justice.

If you allow that a majority of entitled victims of procedural abuses are white men, then it stands to reason that a majority of complainants of procedural abuses will be white men.

It further stands to reason that these white men, who had been conditioned to the expectation of justice, should feel disappointed…and angry.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*The book Angry White Men: American Masculinity at the End of an Era (2014) is by sociologist Michael Kimmel. Dr. Kimmel is a New York Jew with a Ph.D. from Berkeley. His book was reviewed in The New York Times by Hanna Rosin, a Stanford grad, a senior editor at The Atlantic, and the author of The End of Men and the Rise of Women. Ms. Rosin is also  a New York Jew. While neither one’s conclusions can be dismissed offhand, their cultural and class remove from the subjects of Dr. Kimmel’s book makes their identification with those subjects suspect, and Ms. Rosin’s objectivity and access are plainly dubious. From Ms. Rosin’s review: “Kimmel’s balance of critical distance and empathy works best in his chapter on the fathers’ rights movement, a subset of the men’s rights movement. Members of this group are generally men coming out of bitter divorce proceedings who believe the courts cheated them out of the chance to be close to their children.” Contrast this confidently categorical interpretation of men’s and fathers’ complaints to this firsthand account by a father who was ruined by “bitter divorce proceedings”: “The ‘Nightmare’ Neil Shelton Has Lived for Three Years and Is Still Living: A Father’s Story of Restraining Order Abuse.” A comment on Amazon.com credits Ms. Rosin with being sensitive to “real women’s experience.” The story highlighted in the previous sentence chronicles a real (angry white) man’s—whose telephone number is provided in a comment beneath the post.

a New York Jew. While neither one’s conclusions can be dismissed offhand, their cultural and class remove from the subjects of Dr. Kimmel’s book makes their identification with those subjects suspect, and Ms. Rosin’s objectivity and access are plainly dubious. From Ms. Rosin’s review: “Kimmel’s balance of critical distance and empathy works best in his chapter on the fathers’ rights movement, a subset of the men’s rights movement. Members of this group are generally men coming out of bitter divorce proceedings who believe the courts cheated them out of the chance to be close to their children.” Contrast this confidently categorical interpretation of men’s and fathers’ complaints to this firsthand account by a father who was ruined by “bitter divorce proceedings”: “The ‘Nightmare’ Neil Shelton Has Lived for Three Years and Is Still Living: A Father’s Story of Restraining Order Abuse.” A comment on Amazon.com credits Ms. Rosin with being sensitive to “real women’s experience.” The story highlighted in the previous sentence chronicles a real (angry white) man’s—whose telephone number is provided in a comment beneath the post.

A woman I’m in correspondence with and have written about was accused of abuse on a petition for a protection order last year by a scheming long-term domestic partner, a man who’d seemingly been thrilled by the prospect of publicly ruining her and having her tossed to the curb with nothing but the clothes on her back. He probably woke up each morning to find his pillow saturated with drool.

A woman I’m in correspondence with and have written about was accused of abuse on a petition for a protection order last year by a scheming long-term domestic partner, a man who’d seemingly been thrilled by the prospect of publicly ruining her and having her tossed to the curb with nothing but the clothes on her back. He probably woke up each morning to find his pillow saturated with drool. Now her former boyfriend complains that the stir she’s caused by expressing her outrage in public media is affecting his business, and he reportedly wants to obtain a restraining order to shut her up…for exposing his last attempt to get a restraining order…which was based on fraud.

Now her former boyfriend complains that the stir she’s caused by expressing her outrage in public media is affecting his business, and he reportedly wants to obtain a restraining order to shut her up…for exposing his last attempt to get a restraining order…which was based on fraud.

I hope the outraged title of this piece reaches its attention, because the story below exemplifies a modern manifestation of racial bigotry and violence, and it’s one the Southern Poverty Law Center

I hope the outraged title of this piece reaches its attention, because the story below exemplifies a modern manifestation of racial bigotry and violence, and it’s one the Southern Poverty Law Center  The following account is reported by North Carolinian Neil Shelton, a father denied access to his son and daughter for “three years now and counting.”

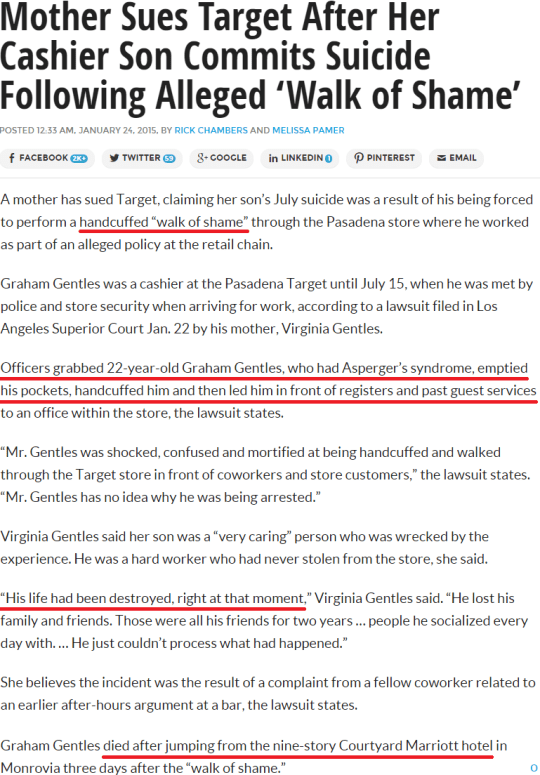

The following account is reported by North Carolinian Neil Shelton, a father denied access to his son and daughter for “three years now and counting.” Mr. Shelton’s allegations are abhorrent yet all too believable. Significantly, none of the criminal allegations introduced against him have held up in court.

Mr. Shelton’s allegations are abhorrent yet all too believable. Significantly, none of the criminal allegations introduced against him have held up in court. On May 29, 2012, which was shortly after I was kicked out of my house by my now ex-wife, I was arrested three times in one day.

On May 29, 2012, which was shortly after I was kicked out of my house by my now ex-wife, I was arrested three times in one day. When my now ex-wife was made aware of my impending release, she took her sister-in-law, who was the director of Surry’s Stop Child Abuse Now (SCAN), and they went to the Surry County Sheriff’s Dept. and had me charged with criminal trespassing.

When my now ex-wife was made aware of my impending release, she took her sister-in-law, who was the director of Surry’s Stop Child Abuse Now (SCAN), and they went to the Surry County Sheriff’s Dept. and had me charged with criminal trespassing. “I’m dangerous broke, as y’all have shut down all my businesses, but I’m not dangerous with $5,000 and no restraining order against me?” With that, I told her I was finished. She said, “Yes, you are,” and we proceeded into the courtroom. I called her a few choice words, and her reply was, “Boy, am I gonna have fun playing with you.”

“I’m dangerous broke, as y’all have shut down all my businesses, but I’m not dangerous with $5,000 and no restraining order against me?” With that, I told her I was finished. She said, “Yes, you are,” and we proceeded into the courtroom. I called her a few choice words, and her reply was, “Boy, am I gonna have fun playing with you.” Upon my release, I showed the judge the two failed commitment attempts, the six not-guilty verdicts for allegedly violating the restraining order, the dismissal of the letter charges, the phone number of the FBI agent who told me the FBI had never been involved and had never investigated the letter—which supposed investigation the other side had used to hold me in jail—and the handwriting analysis proving the lawyer, Zach Brintle, wrote the letter. But the judge still extended the restraining order for yet another year.

Upon my release, I showed the judge the two failed commitment attempts, the six not-guilty verdicts for allegedly violating the restraining order, the dismissal of the letter charges, the phone number of the FBI agent who told me the FBI had never been involved and had never investigated the letter—which supposed investigation the other side had used to hold me in jail—and the handwriting analysis proving the lawyer, Zach Brintle, wrote the letter. But the judge still extended the restraining order for yet another year.

Presuming to deny others’ pain, furthermore, because you believe you can quantify it or “imagine” what it “should” be like—that’s stepping way over the line.

Presuming to deny others’ pain, furthermore, because you believe you can quantify it or “imagine” what it “should” be like—that’s stepping way over the line. I do know what it is to be falsely accused, and the sources of pain are the same, only the suspicion and reproach aren’t an “expectation.” When you’re the target of damning fingers, suspicion and reproach inevitably ensue; they’re a given.

I do know what it is to be falsely accused, and the sources of pain are the same, only the suspicion and reproach aren’t an “expectation.” When you’re the target of damning fingers, suspicion and reproach inevitably ensue; they’re a given.

The lawyers quoted by reporter, what’s more, refer to criminal cases in which sexual abuse is alleged and, consequently, in which the accused are afforded attorney representation.

The lawyers quoted by reporter, what’s more, refer to criminal cases in which sexual abuse is alleged and, consequently, in which the accused are afforded attorney representation.

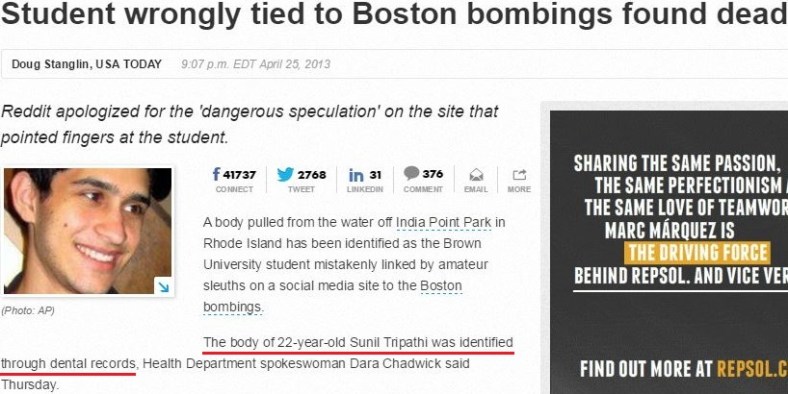

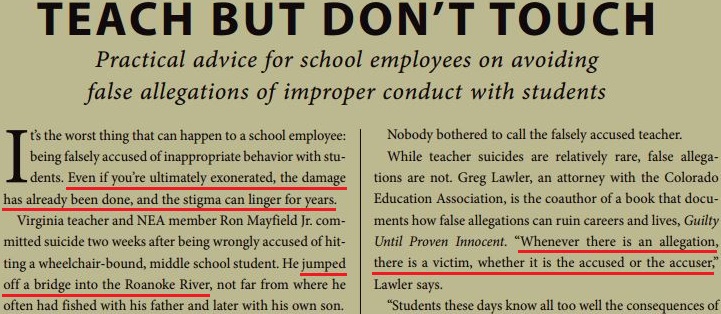

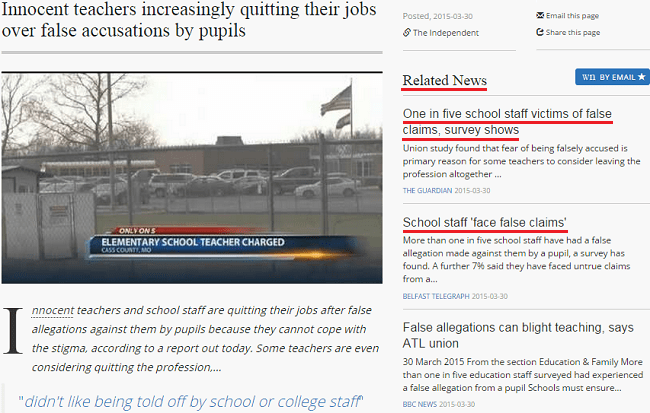

Faith in the conceit that restraining orders are minor impingements on defendants’ lives depends on accepting that being falsely, publically, and permanently labeled a stalker or batterer, for example, shouldn’t interfere with a person’s comfort, equanimity, or ability to realize his or her dreams. Such faith is founded, in other words, on the fantastical belief that wrongful vilification won’t exercise a detrimental influence on a person’s mental state, won’t affect his or her familial and social relationships, won’t negatively impact his or her employment and employability, etc.

Faith in the conceit that restraining orders are minor impingements on defendants’ lives depends on accepting that being falsely, publically, and permanently labeled a stalker or batterer, for example, shouldn’t interfere with a person’s comfort, equanimity, or ability to realize his or her dreams. Such faith is founded, in other words, on the fantastical belief that wrongful vilification won’t exercise a detrimental influence on a person’s mental state, won’t affect his or her familial and social relationships, won’t negatively impact his or her employment and employability, etc.