“Most magistrate judges in both Beaufort County and the state are not lawyers, and the county’s chief magistrate lacks a college degree, state records show.

[…]

“In Beaufort County, four of 11 magistrates are lawyers, according to Terry Leverette of S.C. Court Administration.

“Seven of the county’s judges were required to have a four-year college degree, because they were first appointed after the state changed the education requirement in 2005. Beaufort County’s chief magistrate, Darlene Smith, appointed in 1994, finished high school but does not have a college degree.”

—Luke Thompson, The Beaufort Gazette (Sept. 20, 2010)

In his article “Most county magistrates aren’t lawyers, but education standards are changing,” Luke Thompson reports that in 2010 “only about 13 percent of [South Carolina’s] 311 magistrates” were certified to practice law.

Standards are changing, he relates. The state’s Supreme Court requires that magistrate judges who rule on “check cases” be licensed attorneys (because decisions may levy significant fines).

This degree of legal competency isn’t, however, required to rule on restraining order cases.

“Are lawyers kind of presumptively better qualified to judge cases than somebody who has never had that background? Yes, sure they are,” said John Freeman, a retired University of South Carolina law school professor who sits on a panel that screens state judges. “Would the public be better off? I think probably the public would be better off, and I say that without meaning to disparage or degrade some of our fine magistrates who don’t have full legal educations.”

[…]

It’s not clear if magistrates without legal training are more likely to make bad rulings. Leverette said the state does not keep statistics regarding how many magistrate cases are overturned on appeal. [Note: few restraining order cases are ever appealed to the state courts in the first place.]

Freeman…said magistrates account for a disproportionate number of disciplinary actions. Requiring law degrees might reduce that number, he said.

(Ya think?)

The “check cases” referenced in Mr. Thompson’s story presumably have to do with fraud or nonpayment, i.e., money. In law, a great deal of emphasis is placed on money. Disregarded, however, is that “disciplinary actions” undertaken carelessly, like the casual issuance of restraining orders, can exact a far graver toll than some kited checks.

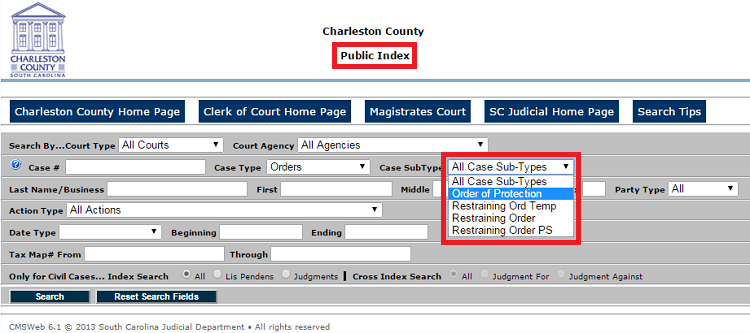

Restraining orders, what’s more, are no less permanent public records than charges of “check fraud,” and these records may be conveniently accessed by the Internet. The “public index” for Charleston County, South Carolina, shows just how conveniently:

Appreciate that the (mere) implications of the (mere) phrase restraining order or protection order include stalking, “terroristic behavior,” battery, child abuse, and sexual assault.

Finally, consider that petitions for restraining orders—which may cost men and women their jobs, security, and access to children, pets, home, and property—may be ruled upon by people whose educational credentials are nothing more than a high school diploma or a degree in library science, and that highly prejudicial and prejudiced restraining order rulings are available for public consumption (by defendants’ friends, associates, students, patients, employers or employees, loan officer, landlord, etc., etc., etc.).

Anytime and for all time.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*The story cited above was killed after it was quoted in this post. Here is a story about magistrates in Pennsylvania. Its reportage is similar.

It’s hard not to hate judges who issue rulings that may be based on misrepresentations or outright fraud when those rulings (indefinitely) impute criminal behavior or intentions to defendants, may set defendants up for

It’s hard not to hate judges who issue rulings that may be based on misrepresentations or outright fraud when those rulings (indefinitely) impute criminal behavior or intentions to defendants, may set defendants up for