That’s a rhetorical question.

Plainly it’s not cool to tell victims of rape how they should feel, particularly if you’re not one yourself. I don’t say that because it’s un-PC to criticize rape victims; I say that because it’s wrong.

Yet goddamn if there’s no shortage of people who have no context to relate either to rape victims or victims of false accusations who presume to defend the former’s right to be basket cases and deny the latter any right to complain.

The previous post examined the vehement rhetoric of one of these self-appointed arbiters of anguish (whose argument seems to run: “I’ll tell you how you’re entitled to feel”).

Pause here for a point of clarification: False accusations can be of a great many acts besides sexual assault, and the phrase false accusation in this post refers to any false accusation.

There’s nothing, of course, to reproach about someone’s sympathizing with victims of sexual assault, as the writer scrutinized in the last post does; it’s compassionate. Presuming to “relate” to the pain of women who’ve been raped, however, is presuming a lot.

Presuming to deny others’ pain, furthermore, because you believe you can quantify it or “imagine” what it “should” be like—that’s stepping way over the line.

Presuming to deny others’ pain, furthermore, because you believe you can quantify it or “imagine” what it “should” be like—that’s stepping way over the line.

Look at enough feminist rhetoric, though, and something becomes starkly clear: The basic contention is that “our” pain is worse than yours. (One gets the distinct impression that all feminist writers consider themselves rape victims by association or genital identification.)

I don’t discount rape victims’ torment, but I do believe this pain “rating scale” is due to be dispassionately tested.

The approach of those who presume to criticize complainants of false accusation is to reduce their trials to something like this: generally speaking, (1) you’re accused, and (2) maybe you lose some friends and your job. Also, (3) if you’re exonerated, you don’t have anything to bitch about, so shut up and go away.

Now here’s what you get when you apply to rape victims the same obscenely reductive analysis: generally speaking, (1) your body is penetrated without your consent or against your express objection, and (2) you’re possibly, if not probably, left with some tissue damage.

Both of these sketchy assessments are about equivalent in their insensitivity (and according to them, the privations of the falsely accused may well be more enduring than the injuries of the victim of rape).

So why is the former assessment popularly conceived to be “fair” while the latter would be denounced as “cruel”?

Is it because false accusation inflicts a psychic trauma and that rape has a physical component? I’ve been run down in the road by a 4 x 4 while on foot. Bones were splintered and crushed. I spent five days in an intensive care ward, and my skeleton and joints will never be the same. I almost lost an eye, and the hemorrhaging came with its own host of consequences. Entire swaths of my body were without sensation. Some months later, I had a cerebral episode and was aphasic for a day (I couldn’t remember, for example, the word October or repeat “no ifs, ands, or buts”). I’d wager the physical trauma I sustained exceeds that of an overwhelming majority of rape victims. Does that make me “more worthy” of sympathy?

Apples and oranges, right? Why? Because the affront to my body was impersonal.

It makes a difference, then, when our dignity and humanity are violated, and we’re treated with intimate disregard.

I don’t know what it is to be raped. I do know, though, what complainants of rape report, and reported sources of pain are shame, outrage, fear, betrayal, a lingering and possibly insurmountable distrust, and ambivalence about reporting the violation based on the expectation of suspicion and reproach from authorities (as well as others) and having to relive the horror, possibly without hope of realizing any form of justice.

I do know what it is to be falsely accused, and the sources of pain are the same, only the suspicion and reproach aren’t an “expectation.” When you’re the target of damning fingers, suspicion and reproach inevitably ensue; they’re a given.

I do know what it is to be falsely accused, and the sources of pain are the same, only the suspicion and reproach aren’t an “expectation.” When you’re the target of damning fingers, suspicion and reproach inevitably ensue; they’re a given.

There’s a misconception about accusation that isn’t really a misconception at all; it’s an empathic dereliction. Facile commentators say people are “accused” as if that’s all there is to it. (I’ve been falsely accused by the same person in multiple court procedures spanning seven years, and I’ve lived with the accusations daily for nine. A man I know has been summoned to court dozens of times; a woman I recently heard from, over 100 times—in both cases, by a single vexatious litigant.)

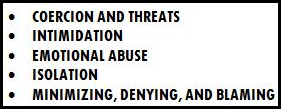

To be accused is to have the state knocking on your door. It’s to be sent menacing notices in the mail or to have them tacked to your residence (endure this long enough, and you stop looking in the mailbox or even answering the phone). It’s to be hauled into a police precinct—if not arrested and jailed—and to be subjected to invasive questioning, if not physically invasive, involuntary examinations. It’s to be treated with hostility and contempt, like a thing of disgust. It’s to become the fodder of gossip and the target of threats. Judgment is a palpable thing, and it’s far worse than a body blow (or even being steamrolled by an onrushing vehicle).

The outrage, moreover, of being blamed falsely isn’t something that can be “intuited.” Here’s how one woman I’ve corresponded with puts it, a woman who was accused by a man who had abused her both physically and otherwise (yes, sometimes the accuser simply reverses roles with his or her victim—and, yes, if you missed it in the parenthetical remark above, sometimes the falsely accused isn’t a man):

There is no “coming out the other side” of a public, on-the-legal-record character assassination. It gnaws at me on a near-daily basis like one of those worms that lives inside those Mexican jumping beans for sale to tourists on the counters of countless cheesy gift shops in Tijuana.

I have sort of moved on; I mean, what else can one do, particularly when one has young children? But the horror, outrage, shame, and, yes, fury engendered by being wrongly accused by a perpetrator, and then having that perpetrator be believed, chafes at me constantly. Some things born of irritation and pressure are ones of beauty, like a pearl, or a diamond, but not this. This is a stoma on one’s soul—it never heals, it’s always chapped and raw, and if you’re not careful, it can leak and soil everything around it.

Would a feminist sympathize with this person? Probably…grudgingly and without making a to-do about it.

Why? If the answer is because she’s a woman, then we’re getting somewhere. The blindness to the damages of legal abuse has a great deal to do with sex. Most of the vehement objectors to legal violations are men—they being the majority of the victims—and they’ve been demonized…because they’re men. This has led to the dim formulation that “falsely accused” equals “male” equals f* ’em.

Absurd, besides, is that arguments like those scrutinized in the last post on the one hand posit that men shouldn’t feel their own pain but on the other hand should show sympathy to women’s. Men are oxymoronically supposed to be stoic and insensitive, er, “empaths.”

Yeah, but not really. Really the conclusion is their pain doesn’t matter. It’s “insignificant” because (tum-tum-tum-TUMMM)…

To whom? Society? It certainly isn’t a bigger problem to its falsely accused constituents. This is a democracy, not an ant colony, and pain isn’t a competition or a zero-sum game. No one’s pain is more “valid” or “virtuous” than the next’s. What the sentiment in headlines like this really means is that the lives of the falsely accused are (politically) insignificant—and the sentiment is a sick one.

Abuse of people is abuse of people, and life-wrecking torment is life-wrecking torment.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*Though its psychic fallout may be indelible, rape ends. False accusation and legal abuse may be continually renewed. People report being in legal contests for years, even many, many years. They report running through tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars. They report being left penniless and in cases homeless. They report living “like a hamster.” They report being in therapy, on meds, and sometimes being unable to work even if their careers haven’t been ruined, and often they have been. They report losing their children, and they report losing the right to work with or be around children. Accusation isn’t an “inconvenience.”

Presuming to deny others’ pain, furthermore, because you believe you can quantify it or “imagine” what it “should” be like—that’s stepping way over the line.

Presuming to deny others’ pain, furthermore, because you believe you can quantify it or “imagine” what it “should” be like—that’s stepping way over the line. I do know what it is to be falsely accused, and the sources of pain are the same, only the suspicion and reproach aren’t an “expectation.” When you’re the target of damning fingers, suspicion and reproach inevitably ensue; they’re a given.

I do know what it is to be falsely accused, and the sources of pain are the same, only the suspicion and reproach aren’t an “expectation.” When you’re the target of damning fingers, suspicion and reproach inevitably ensue; they’re a given.

A scratch, a push, a pinch—which may not even have been real but whose allegation had real enough consequences.

A scratch, a push, a pinch—which may not even have been real but whose allegation had real enough consequences. I’ve written recently about the abuse of restraining orders by fraudulent litigants to punish. What needs observation is that the laws themselves, that is, restraining order and domestic violence statutes, are corrupted by the same motive: to punish. Their motive is not simply to protect (a fact that’s borne out by the prosecution of alleged pinchers).

I’ve written recently about the abuse of restraining orders by fraudulent litigants to punish. What needs observation is that the laws themselves, that is, restraining order and domestic violence statutes, are corrupted by the same motive: to punish. Their motive is not simply to protect (a fact that’s borne out by the prosecution of alleged pinchers). What I discovered was that group-bullying certainly is a recognized social phenomenon among kids, and it’s one that’s given rise to the coinage cyberbullying and been credited with inspiring teen suicide. The clinical term for this conduct is

What I discovered was that group-bullying certainly is a recognized social phenomenon among kids, and it’s one that’s given rise to the coinage cyberbullying and been credited with inspiring teen suicide. The clinical term for this conduct is