It’s surreal to sit in a courtroom knowing you’re the only one aside from the plaintiffs who knows the truth of the matter and that almost everyone else’s impressions are completely wrong. I had this experience (not for the first time) in July. The court staff, for example, thought it remarkable that the plaintiffs in a tort case (a civil trial) were represented by a criminal attorney. Did this mean, they wondered aloud, that the attorney was changing what kind of law he practiced?

I knew the answer: No. There was nothing remarkable about the plaintiffs’ choice to me. The job of a criminal attorney is to pelt judges and jurors with alternative (including screwball) theories to make those judges and jurors scratch their chins and think hmmm. His or her job is to divert scrutiny and blame from his or her client(s).

In the case in which I was recently the defendant, the plaintiffs’ criminal attorney was there to obfuscate, distract, and confuse. The primary question addressed during what was a several-hour procedure was whether I had “contacted” (and thus “harassed”) the plaintiffs by writing ABOUT them.

The plaintiffs’ attorney said I had contacted third parties about the plaintiffs (“literally hundreds”!), that Google Alerts (created by one of the plaintiffs) had emailed them with notices about my online speech, and that I had used the plaintiffs’ names in HTML meta tags (keywords associated with the content of my online speech—see, for instance, the bottom of this post). All of these were alleged to constitute “contact” with the plaintiffs.

(HTML lexical tags were especially emphasized, and the plaintiffs’ criminal attorney called an expert witness, also a criminal attorney, to talk about them. They were alleged to have some kind of spooky—and very sinister—potency: WooOooo-ooo-ooo-ooo-ooo. In fact, Google doesn’t pay any attention to them at all, and they’re completely passive: They just catalog topics that particular posts are about and interconnect those topics within a site.)

For the first time in over 10 years of being prosecuted by the same monsters, I had an attorney, so I didn’t say a word.

If I had addressed the court, however, this is what I would have told the judge: “Your Honor, you can clear up this question of ‘contact’ in 10 seconds by asking the plaintiffs how they learned about anything I’ve ever written. If their answer is not one of the following, there has been no ‘contact’:

- ‘The defendant confronted us.’

- ‘The defendant emailed us.’

- ‘The defendant called us.’

- ‘The defendant texted us.’

- ‘The defendant Skyped us.’

- ‘The defendant sent us a letter.’

- ‘The defendant asked an intermediary to convey a message to us for him.’”

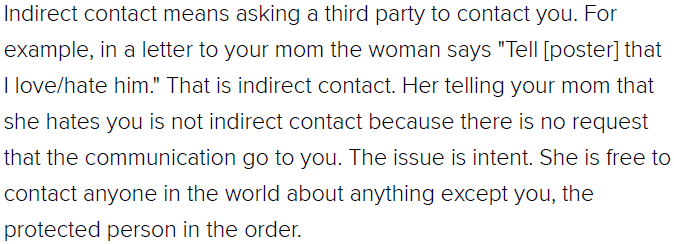

The plaintiffs didn’t even allege that I had contacted them directly, so only option 7 was available. Did I ask a third party to contact the plaintiffs (e.g., “Kindly tell them they’re going to burn in hell and that they should lay in a store of asbestos diapers now”)? No, nor was it alleged I did. Did I ask Google Alerts to email the plaintiffs? No, nor was it alleged I did. Do HTML tags send emails, make phone calls, or write letters? No, nor was it alleged they do.

That simple.

Copyright © 2016 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*Speech ABOUT people, for instance, or legislation or products or institutions (including critical speech)—whether posted on the Internet (“The guy’s a soulless pig!”), megaphoned in the town square (“Obamacare stinks!”), or tacked to a bulletin board (“Monsanto is destroying the planet!”)—is speech protected by the First Amendment, and it does not “contact” its targets. Speech can’t contact; it can only be listened to or ignored. “Google indexed his blog post, and I clicked on the link and read it”: NOT contact. “A friend saw what she wrote and told me about it”: NOT contact. “He used my name”: NOT contact. “She published what I said in court”: NOT contact. “He told my boss I’m a liar”: NOT contact. “She said my [product or service] was unreliable”: NOT contact. Knowledge that criticized parties might read what a person writes in a blog or on Twitter, for example (or on a review site), doesn’t mean the author “intended” for the criticized parties to read it…even if s/he knows they monitor his or her every action.