Restraining orders occupy an exceptional status among complaints made to our courts, because their defendants (recipients) are denied due process, that is, they have no say in the “preliminary” conclusions formed by judges.

Restraining orders occupy an exceptional status among complaints made to our courts, because their defendants (recipients) are denied due process, that is, they have no say in the “preliminary” conclusions formed by judges.

A plaintiff (applicant) waltzes into a courthouse and makes some allegations against a defendant, who is just a name on a form. That’s it. And those allegations are subject to no special standard of verification, which is why the word preliminary in the first sentence is enclosed in quotation marks of contempt: presumed conclusions are seldom revised even when defendants pursue what meager opportunities they may be afforded to challenge and controvert allegations casually leveled against them.

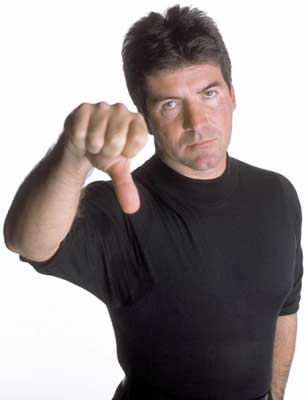

Once a judge signs off on a restraining order, it’s typically a done deal. Which is a problem, because no due process means plaintiffs get to play Simon Says with the truth.

“Simon says he’s a danger.”

Check.

“Simon says she’s a stalker.”

Check.

The restraining order process has devolved into a playground game—all comers welcome!—that is provided a gloss of legitimacy by the stern and forbidding rhetoric and consequences that attend it and the earnest faith it’s afforded by those who don’t know any better, which certainly includes the general public and may include authorities and officers of the court, also.

It’s a sham, a scam, and a shame on our justice system.

Allegations of any nature, including assault (physical or sexual), can be made on restraining orders without applicants being charged a penny or having to satisfy any standard of proof (and these allegations may be permanently stamped on recipients’ public records for anyone to peruse—employers, for example—or entered into public registries). And they can be made straight to a judge who it’s usually the case has been instructed not merely to take those allegations seriously but to accept them at face value.

In fact, contrary to reason, the worse an allegation is, the less it’s to be questioned. The truth of an allegation of violence, especially, is to be accepted as given.

There are even “emergency restraining orders” that may deny their defendants any more than a weekend to prepare a defense (try finding a lawyer on a Thursday who’s willing to represent you on the following Monday), and the standard of credibility applied by judges to applications for these orders is no more demanding. Emergency restraining orders may likelier be approved on reflex because of the implications of the word emergency (I wish I were kidding).

Hysteria is not evidence, and finger-pointing is not fact. Parents scold their children: “Would you jump off a bridge just because everybody else did?” Little kids are exhorted to think independently and not to act on impulse or in sheepish compliance with convention.

Judges, I’m pretty sure, are supposed to do the same.

Copyright © 2013 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com