“Parental Alienation is an act of child abuse, and an attempt by one parent to sever [a] child’s ties with the other parent.”

—Steven Foxworth, DaddysHeart.com

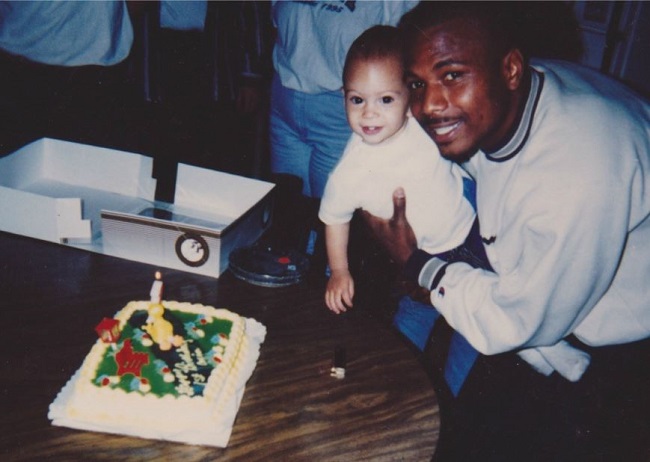

Steven Foxworth had a beautiful daughter, a beautiful daughter whose life he had been excluded from for 12 years, and a beautiful daughter he will never see again.

Nor will anyone else.

Asia Danielle was killed in a car accident in 2011 at the age of 16, and Mr. Foxworth didn’t learn of his daughter’s death until eight months later. Even if he had chanced to see the headline of his daughter’s obituary, published in another state, he may not have recognized it as hers, because his daughter’s name had been changed, which is why his attempts to find her over the years proved fruitless.

Asia Danielle Foxworth a.k.a. Danielle Westbrook was tragically killed in a car accident in 2011. Her father, Steven Foxworth, was informed of his daughter’s death by a mailed notice asserting that he had no entitlement to her estate. Mr. Foxworth was unlawfully denied any contact with his daughter for 12 years and wasn’t told her name had been changed.

For most of her brief life, the girl Mr. Foxworth had known as Asia Danielle Foxworth was Danielle (“Danni”) Westbrook.

After Mr. Foxworth separated from Asia’s mother in 1998, he was “threatened to stay away from his own child’s daycare that he enrolled her in.” Mr. Foxworth petitioned the court and succeeded in having his parental rights acknowledged “concerning phone/standard physical visitation, and full access to all pertinent info, i.e., school and medical records,” but Asia’s mother, Rusty Dawn Skipper, was granted full custody, and she moved to North Carolina and, according to Mr. Foxworth, declined to observe the court’s order that Asia be brought to Georgia for visitation with her father. She furthermore provided Mr. Foxworth no contact information and in 2000 changed Asia’s surname to Westbrook, that of her then fiancé, without Mr. Foxworth’s consent.

Though he paid child support, never knowing if it reached its intended recipient, the only communication Mr. Foxworth received from Asia’s mother concerning his daughter in 12 years was a legal notice, sent after his daughter’s death, apprising him that he had no claim to her estate.

That’s how the mother of his daughter informed Mr. Foxworth that his daughter was gone.

Mr. Foxworth reports that even seven months after Asia was killed, her maternal grandparents represented her as living when he contacted them, which he had faithfully done for years, even annually singing “Happy Birthday” on their answering machine, hoping the song would be shared with his estranged daughter.

Mr. Foxworth’s is a poignant story of a father’s alienation from his child that includes collusion by family members and the state. A more detailed version can be found on Mr. Foxworth’s tribute to Asia, DaddysHeart.com, under the tab “Asia’s Law.”

“Asia’s Law” is Mr. Foxworth’s proposal to stop parental alienation.

“Asia’s Law” will stand on the principle that no one parent has the right to infringe upon the legal parental rights of another parent.

“Asia’s Law” will promote the enforcement of standard child visitation for noncustodial parents as rigorously as child support is enforced for custodial parents. There will be a governmental arm that works with Child Support Enforcement Services that regards court-ordered visitation as seriously as child support arrearage. In the current construct, the message is sent that the value of money to take care of a child is more important than the value of a child’s having the love, affection, and guidance of his or her other parent.

“Asia’s Law” will promote the enforcement of standard child visitation for noncustodial parents as rigorously as child support is enforced for custodial parents. There will be a governmental arm that works with Child Support Enforcement Services that regards court-ordered visitation as seriously as child support arrearage. In the current construct, the message is sent that the value of money to take care of a child is more important than the value of a child’s having the love, affection, and guidance of his or her other parent.

“Asia’s Law” will also make it illegal for a custodial parent to change the name of a minor without the other natural parent’s consent—in any state.

Additionally, “Asia’s Law” will mandate that a non-custodial parent give blood (except in cases of religious exemption) so that if a child needs blood for any medical reason, it will be there for him or her.

“Asia’s Law” will save lives—emotionally and physically. We need this law passed to protect families.

My daughter, Asia Danielle Foxworth (“Danielle Westbrook”), is no longer here, but if there had been a law like this in place while she was living, she could not have been kept from me—under the radar for 12 years. Further, her “name change”—save legal adoption (which I would not have consented to)—could never have been permitted. Lastly, if my daughter would have survived her fatal car accident and needed blood, she could have had mine, providing it was stored for her. There are also children who have natural ailments; blood donation from a natural parent could save their lives, even if that other parent lived in another state. Too many are suffering. We need “Asia’s Law” passed. I have my story, but there are countless others. Parental Alienation is an age-old phenomenon and stereotypes typecast parents, especially fathers. The bottom line is no child should be kept from a loving parent—illegally and/or out of spite. If through “Asia’s Law” families are reunited, the rights of noncustodial parents respected, and lives saved, my daughter’s transition will not have been in vain.

~Steven Foxworth

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*Compare Mr. Foxworth’s story of parental alienation to that of estranged father Neil Shelton: “The ‘Nightmare’ Neil Shelton Has Lived for Three Years and Is Still Living: A Father’s Story of Restraining Order Abuse.” Attention to Steven Foxworth’s story was brought to the author of this blog by the Georgia-based Kayden Jayce Foundation, a nonprofit devoted to remedying parental alienation and legal abuse.